9

pacific voyagers

The Tuamotus, March 1768

It was a momentous day when we finally ‘turned left’ to head north up the east coast of Australia. It had taken some two and a half years since we left Port Lincoln to get this far, stopping at different ports from time to time for work. Not quite as dramatic as escaping from the frozen grip of the Horn, not quite ‘slippers and underpants’ weather, but still, our first entrée into Pacific waters. Almost immediately, the wind gentled and the waters warmed from the eastern current that sweeps tropical waters south down the coast. From here on the weather would only get better and the harbours safer. We stayed a night beneath the great granite lighthouse on Gabo Island (coming almost too close for comfort) and watched the penguins swim like shooting stars in the phosphorescing water. Here and there, larger shapes stirred the deeper waters, lighting up the darkness with an eerie and ominous glow.

Our first port of call was in Eden. Aptly named, the town nestles in Snug Cove, lined with white beaches and dark forested mountains. My grandparents had forwarded all our mail to the local post office, including a bundle of marked assignments and letters from school. Having just started high school, one of my new teachers had suggested that, instead of completing the designated assignments, I could swap them for a project on the area I was visiting. Eden’s famous killer whale museum, with its remarkable story of cooperative hunting between humans and orcas, became my first self-directed project.

Twenty years later this small school project would transform into my first book.

Fifty-four days after leaving the Strait of Magellan, in the small dark hours of morning, the Étoile’s captain ordered a change of course by a single compass point. He did not say why. It was as if he had smelt land: some all but imperceptible refraction of wind, wave or atmosphere. The lookout on the Étoile soon sighted land from the mainmast, even as the Boudeuse sailed blindly ahead. Whatever Commerson thought of their manners, the Breton sailors knew the sea.

Just after sunrise, the lookout confirmed a chain of small islands to the south-east gradually emerging as the sky lightened. Before long, the clear weather allowed everyone on the poop deck to see the archipelago clustered in the distance.

Another island appeared to the west. A verdant wooded mound rimmed in a fine line of white sand. Were it not for the height of the vegetation and the tall coconut palms that sprouted above the canopy, it might have remained entirely invisible. They imagined themselves the first people to sight this island in 165 years since the Portuguese navigator Pedro Fernández de Quirós had passed this way, although there was no guarantee that this particular island was one that he had described.

As they approached, two dark and naked figures stood out against the pale sand, leaning on long spears. Fifteen or twenty more emerged from the forest edge near a cluster of small huts. The ships hove to and moved in unison along the shore. The watchers retreated, leaving the two men standing firm, raising their lances and striking them on the surface of the water. It was astonishing to imagine how people could have populated such a tiny island, not much more than a league across, and surrounded by a ring of white foaming breakers. Someone lit a fire on the northernmost point, although whether in welcome or warning was impossible to tell. There was nowhere safe to land in any case.

‘Who in the devil went and placed them on a small sandbank like this one and as far from the continent as they are?’ demanded Caro.

As if they could not have sailed there themselves.

It is one thing to travel across the colonised world, where the exotic is just a variant of the familiar: Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, English or French.

‘All Europeans are fellow countrymen when they meet so far from home,’ Lapérouse once said.

It is quite another to encounter a people, a culture, a language, a history, entirely divergent and distinct from one’s own, where the only things we share are our common human traits: hunger, thirst, fear, love, sex, humour, anger, sociality. For all our commonality, there is so much to be misunderstood.

Perhaps Jeanne did not think it so strange that there should be naked people standing on this small sandbank in the middle of the Pacific. No stranger, surely, than finding a young peasant girl from La Comelle, in a man’s attire, floating past on a ship made of oak, hemp and cotton.

The island of Akiaki was formed by tip of a seamount that rises 3420 metres from the ocean floor. Like an iceberg, its bulk lies below the surface; the coral atoll itself sits barely a metre above sea level. The island is part of the largest chain of coral atolls in the world. The 80 islands that make up the Tuamotu archipelago – meaning the distant isles – extend across some 850 square kilometres of ocean.

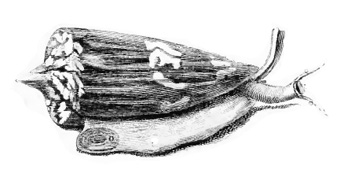

The great oceanic expansion of Polynesian culture, in the thousand years before and after the Common Era, had been built on an unmatched technology of shipbuilding and navigational expertise. And even among Pacific Islanders, the Tuamotuans were regarded as master shipbuilders and navigators. Akiaki may have no permanent population living on it today, but then, as now, it would have been visited regularly to harvest coconuts, birds or green turtle eggs. Its closest neighbour, Vahitahi, is only 41 kilometres south-east, a daytrip for a pirogue.

These oceanic people, watching from the shore, had seen ‘floating islands’ drift past under their golden-foliaged trees before. The Englishman John Byron had made contact with residents in the Tuamotus just the year before Bougainville’s ships sailed past. The people on the shore of Akiaki would have heard stories from their grandparents of Dutch ships, like those of Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire in 1615–16, or Jacob Roggeveen in 1722. Or they might have heard even older stories of the Spanish ships under Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira sailing through the Tuamotus from Peru to the Philippines in 1595.

Others soon followed in Bougainville’s wake. Two years later, Cook named Akiaki atoll Thrum Island. The Spanish navigator Domingo de Bonechea sailed through the region in 1774 and the Russian Otto von Kotzebue in 1815.

As it happened, the Tuamotu islands eventually came into French possession when Commodore Abel Dupetit Thouars came to the aide of exiled Catholic missionaries and, somewhat unilaterally, seized control of Tahiti and all of its associated assets in 1838, giving rise to what is now French Polynesia.

Europeans have continued to sail past the Tuamotus, seeking to impose their own cartography on an isolated watery world that defies their understanding. Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife Fanny passed by some of the atolls on their yacht Casco in 1888.

‘Lost in blue sea and sky,’ Stevenson described the island. ‘A ring of white beach, green underwood, and tossing palms, gem-like in colour; of a fairy, of a heavenly prettiness. The surf ran all around it, white as snow, and broke at one point, far to seaward, on what seems an uncharted reef. There was no smoke, no sign of man; indeed, the isle is not inhabited, only visited at intervals.’

In Jack London’s South Sea Tales, the captain of a burning ship must relinquish control and navigation of his ship to the ‘memory chart’ of an old Pitcairn Islander, who guides them to safety through the shifting waters of the Tuamotus. But efforts to appreciate Polynesian expertise and knowledge of their own region invariably seemed to falter against the ironclad determinism of the European imagination. I can’t help but wonder what old Polynesian navigators would have thought of Thor Heyerdahl’s drifting balsa-wood raft Kon-Tiki bumping into Raroia to ‘prove’ a mythical Polynesian migration route from South America in 1947. It wasn’t until the 1960s that anyone thought to ask the Polynesian navigators themselves where they came from and how they spread so effectively across their vast empire.

If the unfamiliar spectacle of land and people was not enough to bring Jeanne to the deck after so many weeks at sea, perhaps the birds would have. They filled the sky and the shore around the tiny island in ‘infinite numbers’. Their wavering cries and the pungent smell of guano would have wafted across the ships, even as they stood offshore. So many birds promised rich fishing grounds. These mid-oceanic islands – so close to marine food supplies and so far from the malign influence of mammals – were clearly a paradise for birds.

But not any more. French research led by Caroline Blanvillain found that several critically endangered species – two doves, a sandpiper, a reed-warbler, a crake and a curlew – had all dramatically reduced their range across eight different islands since 1922. Polynesian rats, which first settled with humans on the islands around 300 BC, then European rats from the 1800s, are responsible for most of these localised extinctions, with cats an added burden.

In the last twenty years, sea levels have risen in the Pacific, storm surges have increased, the incidence and severity of cyclones have magnified. Can the tiny coral atolls dotted across the Pacific survive this onslaught? The answer depends on what you mean by survive. Sea-level rises average between 3 and 5 millimetres per year – well within the tolerance limits of most reef systems. Coral continues to grow upwards to maintain its proximity to sunlight. Cyclones do unprecedented damage, but within the protective ring of reef, many atolls gain sediment in storms rather than lose it. But the answer for humans is different. Humans and their associated animals and crops are not so tolerant of saltwater incursions. And human activity, removing vegetation and altering shorelines, seems to dramatically increase the damage done by weather.

I met a woman from Samoa at a friend’s wedding about fifteen years ago. When I asked her which island she was from she laughed and said I would not know it. She explained to me that at high tide, her home island was almost completely submerged now. The pigs, which spent most of their time foraging for crustaceans on the reef, were all but aquatic. The people too relied mainly on the sea for food – their only transport was by boat and their houses had to be built higher and higher to keep free of the encroaching waters. It was getting harder and harder to grow taro in the salty soil and only the invincible coconuts provided a reliable source of vegetable. Her home island was a day’s boat trip from the nearest island with a radio, a week away from anywhere with a runway for small planes. She was right – it was almost impossible for me to even conceive of people living in such an isolated and vulnerable place. And I wonder now, so many years later, if anyone is still living there.

I am surprised to realise that the sea does not rise evenly across the earth. Strangely, it rises faster in some areas than in others. In the Solomon Islands the sea is rising by an average of 7–10 millimetres per year, three times faster than the global average. In the north of the country, the estimates are 16.8 millimetres per year. In 2016, five reef islands were lost in the Solomons. Nuatambu Island, home to 25 families, lost half of its habitable area and eleven houses have been washed away since 2011. Many villages have been relocated inland, onto higher ground, although this is not an option for coral islands. Even the capital of one province, Taro, is set to relocate its 600 residents, four churches, hospital, school, police station and courthouses to a larger island. The former market site is currently chest-deep under water. They have already been evacuated three times after the island was swamped by tsunamis triggered by earthquakes.

In the 1960s the French finally found a use for their far-flung colonial outpost on the other side of the world, and detonated mushroom clouds over Mururoa and Fangataufa atolls, some 400 kilometres to the south of Akiaki and 1200 kilometres south-east of Tahiti, showering plutonium across 3000 kilometres. The impact of plutonium in the Pacific environment – not just from French testing but also from US testing in the Marshall Islands, UK testing in Australia and Soviet dumping of radioactive liquid waste in the north Pacific – has barely even been examined. Mururoa and Fangataufa remain off limits to the public. Leukaemia and cancer have become major causes of mortality among Tahitian workers exposed during the testing. But no independent monitoring of environmental impacts has been permitted by the respective authorities.

The environmental future of these far distant islands, so rich and idyllic when Jeanne first saw them and so remote from the worst excesses of human activity, looks surprisingly and unfairly bleak.

My parents owned a little brass plaque when I was small, glued to a cheap black frame that sat on our bookshelves. When we moved onto the boat, Dad fixed it to a block of wood and attached it to the bulkhead.

I don’t recall the picture on it exactly. I’m sure there were distant mountains, trees and probably someone with a bundle tied to a stick, looking longingly into the distance. But I remember the poem, long after the plaque itself was lost.

Don’t feel afraid of anything

Through life just freely roam

The world belongs to all of us

So make yourself at home.

It was a twee little piece of kitsch, but an apt motto for ‘boaties’ who sought to free themselves from the constraints and regulations of suburban life. You can sail, more or less, where you want on the open ocean. You can come and go as you please, with only the weather to dictate terms. Harbourmasters and authorities rarely pay you much attention, beyond directing you to the nearest wharf or suitable mooring point or, in more remote areas, swinging down in aircraft to check for smuggling.

That little poem gave me a great sense of confidence, as a child, that I could find a home, or make one, wherever I went. That home was something you took with you, not something you left behind. It was a notion that echoed in my mind every time I launched my kayak or rigged the dinghy in a new port and set off to explore the secret creeks and hidden bays, with my cat standing in the bow oblivious to the risk of falling.

But I cannot escape the fact that it is also a perfect motto for a colonising culture, for those who sought to make new homes in new lands across the seas. We expect to be made welcome wherever we go. And I can’t help but see myself in the ignorant and arrogant responses of those explorers who so often refused to accept that, most of the time, they were quite simply very clearly unwelcome.