13

nature’s beauty and terror

Port Praslin, July 1768

When we sailed along the north coast of New Guinea in the late 1980s, few of the villages had roads. Their traffic was mostly by sea, in small boats and canoes or by foot along narrow muddy tracks, barely big enough for two people, that trailed up over headlands between the beaches. At high tide the water rose beneath the thick overhanging vegetation and foot traffic splashed through knee-deep waters along the invisible beach, or waited for the tide to turn. The isolation kept the villagers safe from unruly ‘rascals’ in the towns, although it was never possible to arrive in these villages unexpected. Our presence was telegraphed along the coast from boat to canoe, from village to village.

Canoes floated on offshore reefs: heron-like sentinels standing in watchful anticipation of fish and noting the approach of unfamiliar vessels. Those with fish to sell sped towards us, while others paddled back to shore or slipped swiftly away under blue tarpaulin sails.

The mirrored waters reflected the forests and mountains above so perfectly that it was sometimes hard to be sure where land ended and sea began. Territory here, despite the French origins of the word, slips along the edge of the coast and extends far out to sea. There was no mistaking when we crossed into each of these aquatic territories, around a headland, into a bay. Unlike in Australia, the seas here are not some kind of amorphous national or international waters giving free passage to any who sail upon them. Here the water is owned, claimed, possessed and defended. As we approached we prepared for the inevitable inspections, the expressions of mutual respect, the dutiful exchange of goods. It is an obvious and unavoidable courtesy.

And yet the Boudeuse and Étoile ploughed on regardless across ancient tribal boundaries, swatting away local resistance as if it meant no more than the irritation of mosquitoes that plagued them whenever they came too close to shore.

The rain fell relentlessly, day and night, on their arrival at Port Praslin, not unlike standing beneath some celestial waterfall never-ending in its generosity. Even when the weather seemed to pause to draw breath, it reconsidered, sending sudden dark squalls scudding back across the bay.

For all the inclemency though, this bay on the southern tip of New Ireland was a safe one: a secure anchorage surrounded on three sides by steep heavily wooded slopes, an abundance of freshwater running to the shore and – best of all – it seemed uninhabited. The people of these islands had made no secret of their antipathy towards visitors. Sometimes they arrived fully armed in their canoes, paddling at great speed with blood-curdling cries – bows raised, ready to strike with piercing arrows. Other times the islanders waved them closer with branches of peace. They grinned as they approached the ships, teeth stained red with betel juice, before suddenly striking with spear and arrow. No warning shots deterred them – only bloodshed caused them to cry out in surprise and retreat. They hovered, just beyond musket range, shouting and rattling their spears, flashing their bare arses in a universal gesture of contempt.

But here, there was no-one. Those on board the ships felt safe from other people, if not from each other. There was no escaping their own kind, not even on the far side of the world. They found the remains of an English camp at the end of the bay – just a few months old – from the same ship that had preceded them in the Magellan Straits, in Tahiti and now here. What strange magnetism drew them together, across thousands of miles in which they might have gone in any direction?

If they sometimes thought they heard the shouts of men from high up in the hills, they were left unmolested. No-one came for the small canoe they found stored at the far end of the bay, nor the camp with remains of recent meals of shellfish and boar.

Perhaps the place was deserted because there was no food. They had hoped for coconuts, bananas or other fruit that might alleviate their scurvy. They made a camp on the shore where the sick might rest and recuperate but it did them little good. What fruit they found had been picked over by pigs. The cabbage palms were fiercely defended by a swarm of giant ants. Even the fishing was poor.

‘Our crews are worn out,’ wrote Bougainville. ‘This land is providing them with nothing more than insalubrious air and extra labour.’

They did such repairs as they could to the ships. The timber, at least, was good – some for burning and some for the masts and spars. And there was an abundance of water. No fewer than three streams plunged down the hillside onto the beach. The first was allocated to resupply the drinking water of the Boudeuse, the second for the Étoile and the third for washing.

When the weather cleared, briefly, it did so without constraint, to the fairest day imaginable. They lay on fine white sand lapped by turquoise waves and admired the waterfall from which the Étoile drew water, which was more spectacular than anyone could possibly imagine.

‘Art would struggle in vain to produce at Versailles or Brunoy what nature has cast here in an uninhabited spot,’ Bougainville declared. ‘What hand would dare to build the leaping platforms held back by invisible links whose graduations, almost regular, promote and vary the spilling flood, which artist would have dared to create these storeyed masses that make up basins to receive those sheets of crystal water, coloured by enormous trees some of which rise up from the basins themselves? It is quite enough that there are privileged men whose bold brush can trace for us the picture of the inimitable beauties. This waterfall would deserve the greatest painter.’

Nature overflowed in abundance, if not utility, and Jeanne and Commerson lost no time in making their collections. The forests were filled with an infinity of insects, beautiful and bizarre. Phasmids stalked and swayed on branches – some like spiked thorny devils, others like delicate leaves. The trees were filled with parrots and beautiful turtledoves.

Bougainville, though, was more interested in the shells on the shoreline.

‘The reefs that line the coasts contain treasures of conchology,’ he wrote. ‘I am persuaded that in this respect we have collected here a great number of new species.’

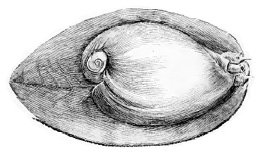

And yet he mentions only two species – an elegant heart-shaped bivalve and an abundance of hammer oysters.

I’m disappointed that he doesn’t mention any other shells, and even those he does are not particularly exciting. A few years later, another French naturalist, René Lesson, provided details of the nautiloids and giant clams that are so abundant in these waters. He lists shells whose French names I don’t recognise, but the oysters, limpets, nerites, conches and strombs are familiar. Jeanne must have collected shells here too. Like Tantalus reaching for waters that always recede from his grasp, I search for a reflection of Jeanne in these accounts, but all I can see are the strange wandering eyes of the stromb shells on the reefs looking back at me with mutual incomprehension.

Lesson also described huge baler shells that New Guineans used to empty their canoes of water. I have a soft spot for these big volutes, which can grow up to 45 centimetres long, with their raised siphon and their vast foot spread like an ornate picnic blanket. I used to try to preserve the smaller volutes intact when I was given them by fishermen, but their colourful feet always retracted and faded in death, no matter how I pickled them. My baler shell, the largest in my collection, stands empty: its apricot-pink interior a pale reminder of the animal that once inhabited it.

Commerson, as usual, remained silent on the matter of shells, even when everyone else was collecting them – including Jeanne. And I am beginning to wonder if I will ever find them at all.

Commerson made hardly any entries in Duclos-Guyot’s diary during their stay in Port Praslin. One would think he must have been busy collecting specimens here, or at least examining the specimens Jeanne brought him. And indeed there are many drawings of birds and plants and insects labelled ‘Nouvelle Bretagne’ in the archives of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. The spiky phasmid described in Bougainville’s journal made it back to Mauritius at least. There is a picture of it among the plates of Commerson’s insects. Nearby is a tiny little spiny orb-weaver – a family of spiders so brightly coloured and bizarrely shaped that they look more like alien spacecraft than arachnids. The description tells me that it is red, so I assume it is Gasteracantha aciculata. A zebra moray eel pickled in alcohol, with its bold black and white stripes, is the only other specimen I can find from this region that has made its way back to France.

I am surprised they collected so few plant specimens from Port Praslin, but many of those that they did collect are now type specimens – the first of their kind to be recorded. Strange and bizarre tongue ferns and spikemosses, asplenium, aspidium and polypodium ferns, lilies, exquisite rock violets and beauty berries, trees with sea trumpet flowers, terminal buds and medicinal fruits. The ferns are particularly beautiful. They could have been pressed yesterday. Another common plant, now known as Bikkia commerconiana, has such long narrow flowers that I wonder what pollinating creature, moth or bird, might have a snout fine and protracted enough to reach its nectar.

One of the beautiful rock violets from Commerson’s collection has found its way to a herbarium in Geneva. It is now known as Boea magellanica, but it has previously been known as Boea commersonii and also gone by the name of Beau. A note on the specimen explains why.

The name of Miss Beau, niece of a chaplain of St Honore, who followed Commerson in the voyages, and was made known as woman by the Tahitians in spite of her disguise.

This is clearly an oblique reference to Jeanne, but somehow conflated with Commerson and his brother-in-law, Father Beau. It is an old note, perhaps from the eighteenth or early nineteenth century. The handwriting of this note could be Commerson’s but I don’t think it is. His name is written very differently from the way Commerson writes it, with a small capital C and a short s. And several other letters are distinctly different too. Whoever it comes from, whatever its origin, this version of the story is interesting, not just because it stresses the virtue of Commerson’s assistant, but also because it links Jeanne back to Toulon-sur-Arroux and to the Beau family, a link which was only discovered in the 1980s by Henriette Dussourd.

It’s another strange clue, simultaneously misleading and revealing, that leaves me even more puzzled than I was before. I wonder what other overlooked clues there might be on other specimens, in other journals. There are boxes and boxes of Commerson archives in the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle and elsewhere: journals, manuscripts, images, letters, scientific notes and lists, as well as thousands of specimens with tiny notes attached in herbaria around the world. I cannot read them all. Many of them are in Paris and I can only afford a couple of weeks to visit, a rare luxury. I don’t have time to go through all of the archives hunting for hints that might shed light on Jeanne. It would be an insurmountable task to try to classify, catalogue and analyse them all.

I worry that I rely too much on the published records. And often these transcriptions skip material from the original journals that they think is not interesting: too technical, too nautical or too scientific. These are often the very things I am most interested in.

Sometimes even an absence of information is useful – when someone stays silent on a topic that everyone else speaks of, when someone mentions something out of turn. It is the little things – the notes that sound just slightly out of tune – that reveal the most.

On 18 July, Duclos-Guyot reported, in a few short lines, on the usual daily activities of the ships, much as he had on previous days, and much as he would do on the days after. Nothing was happening. It had been seven weeks since Jeanne’s confession to Bougainville and another eight weeks since her ‘discovery’ on Tahiti. But at some stage Duclos-Guyot added a note in the margin.

‘It has been discovered that the servant of M. Commerson, the doctor, is a girl who has been dressed as a boy.’

His pen trailed off on the final letter with a wavering and uncertain scroll, as if he didn’t quite know how to finish his thoughts on this matter or if he should even have mentioned it. I am not quite sure what to make of this either.

We had barely dropped anchor off the New Guinea mainland in Milne Bay before the main fleet of canoes was launched, overflowing with a few men, but mostly women and children. They poured over our boat, peering through portholes and down hatches.

‘They are surprised to see a national on a boat like this,’ said one of my crewmates, a New Guinea woman who lived in Cairns and who sailed to Madang with us. ‘They think only white people sail on these boats.’

She was probably right – but the fact that the crew were all women, apart from my dad, might also have been surprising. I didn’t think much of it at the time – it was nothing out of the ordinary. And I was too busy keeping out of sight. My fair, straight hair was clearly strange and exotic enough for all the young girls to want to stroke it adoringly.

The young men were not so adoring. The look in their eyes was of a different nature. Sometimes they would come aboard, helpful and deferential to my father, offering to guide us from one anchorage to another. They arrived on one occasion just as I had started winding up the anchor, a task I had been doing since childhood. There is a knack to shifting a weight efficiently and steadily, whether it is hauling on the sheets to pull up a sail or winding up an anchor – a rhythm to the heave and haul, allowing momentum to ease the load, working with the rise and fall of the ship, or using resistance to your advantage. Being small, I had learnt these techniques young, to maximise what strength I had. But these young men impatiently waved me aside, anxious to show a girl how it should be done. They yanked on the winch handle, which immediately choked and jolted with an iron bite. They glared at me as they struggled to turn the handle, as if I had tricked them by making it look too easy. The awkward impasse was only alleviated when Dad took over the task after coming to find out what had caused the delay.

It seemed strange that everywhere we went in New Guinea, there were people. It felt more crowded here than in any busy city. There was no escape from scrutiny – every step we took was watched, noted and policed. There was no section of coast, no coconut tree or beach, that was not owned by someone, or claimed by a community. I had grown up in a world where the coastline could not be privately owned, where access to the intertidal zone was almost never obstructed. On a boat, we were free to come and go as we pleased. We could moor wherever we liked, in front of million-dollar mansions, or in bays where no-one lived and no roads reached. We could step freely onto any shore and explore the coastline. We caught fish from the waters, ate oysters from the rocks, collected shells and treasures, and cooked our meals on fires made of driftwood on the beach. We came and went and asked no-one’s permission.

But we could not do this in New Guinea. Here we were foreigners, white and (mostly) women. This was not our place.

I had always thought my freedoms were a right, and now I wonder how much of this is simply privilege and entitlement. But either way, I do not want to give them up, any more than did those first Europeans who sailed unwelcomed along these uncertain, uncharted shores.

It must have felt like nature, in all its vigour and vehemence, conspired against Bougainville’s small fleet. The constant bad weather prevented work. The astronomer Pierre-Antoine Véron was afraid that an impending eclipse, visible only in the southern hemisphere, would be obscured. Over the course of the voyage he had made thousands of readings and measurements that greatly corrected the errors of previous navigators and cartographers. This was the first voyage on which longitude was consistently measured astronomically. On the day of the eclipse the showers cleared enough for his observations to be made. Véron used his records of lunar distance and the calculations of longitude taken at Port Praslin and the Strait of Magellan to calculate, for the first time, the vast size of the Pacific Ocean.

In late July, a sailor was bitten by a small black sea snake with a white head. Ahutoru was certain the boy would die. The young lad complained of pain, which worsened as the surgeons forced him to walk, thinking this would help him sweat out the toxins. The walking might well have saved him from further fatal paralysis. The boy collapsed and went into convulsions and they administered opium. But the next day, he started to recover, much to Ahutoru’s amazement.

And then there was the earthquake. An hour before midday a rumble rose through the ships at anchor and continued for two minutes. The waters rose suddenly around the feet of those collecting shells on the reef up to their chests and then fell, as if nothing had happened.

Even the earth beneath their feet did not want them to stay.

I cannot tell you one way or the other what happened at Port Praslin on 22 July 1768. I know what I think, but others will not agree. I can only show you what was said, what was not and what was crossed out or erased. You will have to make up your own mind.

Bougainville mentioned the weather and the earthquake in his journal, even though the earthquake was not sufficiently interesting to include in the official publication.

These 24 hours have been 24 hours of rain and bad weather . . . we have been unable to sail, the winds being S and the sea very rough. At 11 am there was an earthquake which we felt on both the 2 vessels . . . On the shore, the sea rose and fell by about 4 feet in height . . . The earthquake was not extensive and caused no appreciable damage . . .

Caro’s journal was much the same.

It has rained almost continuously since we have been in this harbour . . . We are awaiting fine weather to get out . . . At 11 this morning we felt a movement in the ship that went on for approximately a minute which had the same effect as one feels aft when they are dancing on the forecastle . . .

Fesche displayed even greater brevity.

The officer reported that outside the winds were S, stormy gale and that the sea was very wild, at 10.15 am there was an earthquake.

Nassau-Siegen told us more, but later changed his mind and rewrote his account without any mention of Jeanne.

On the 21st at around 11 am the effects of an earthquake were felt very distinctly on board our ships . . . The sea rose very high at the time of the quake but fell right away. Dampier says it is a common happening in the country. The sailors discovered on board the Étoile a girl disguised in men’s clothing who worked as a servant to M. Commerçon. Without suspecting the naturalist of having taken her on for such a painful voyage. I like to accord to her alone all the honour for such a hardy enterprise, forsaking the tranquil occupations of her sex, she had dared to face the fatigue, dangers and all the events one can morally expect on a navigation of this kind. The adventure, I believe, can take its place in the history of famous girls. After taking possession of the island by leaving an inscription as evidence we left this port on 24 July, well supplied with wood and water.

Vivez says much, changes much between different versions and leaves us uncertain of what he means to say.

If the reader remembers the facts that I have described to him of Cythera, he must believe that there was no great doubt on the decision about the sex of our so-called eunuch. She remained on our ship where it can be appreciated there remained no doubt in anyone’s mind after what had happened but since there was no physical evidence, she dealt with the accusation by issuing some challenge to the servants who promised her an examination which occurred at the next place of call in spite of two loaded pistols she always carried by way of precaution and which she took good care to show them to impress them. Going ashore, one fine unhappy day eleventh of this month when I do not know what had happened to the pistols, after having gone botanizing her master left her ashore to look for shells when having seized the pistols we visited the barrel and when we came to fire the lock we discovered the touch-hole which removed all the doubts and the servants who were there drying the washing took advantage of the moment and found in her the concha veneris, the precious shell they had been seeking for so long. It was in fact a service that we rendered to this girl that we will now call Janeton This examination greatly mortified her but she became more at her ease, no longer compelled to restrain herself to stuff herself with cloths. She remained blushing as a man finished the voyage very pleasantly, having suitors on all sides but we still admit to ignoring the just cause of her metamorphosis who did not lessen her fidelity to her master. She ended up marrying a King’s blacksmith at the Isle de France where I left them and have learned since that she was running a very happy household.

I cannot tell when Duclos-Guyot penned his note about Jeanne’s discovery but he writes it in the margin of the following note, on 18 July. There is no entry for the 21st or 22nd.

The weather is fine enough. The Boudeuse’s boat has collected water and ours was used to carry wood. There was a lot of rain overnight.

Only later, in Mauritius, would Commerson write his own version of events, indirectly, when he adamantly declared that Jeanne had ‘evaded ambush by wild animals and humans, not without risk to her life and virtue’ and had completed her journey ‘unharmed and sound, inspired by some divine power’. And finally, he takes a shot at an unnamed ‘detractor’, who can surely only be Vivez: ‘If by chance she obtains glory or fame, the detractor himself may fall into this poet’s curse.’

In a modern biography of Jeanne Barret, English lecturer Glynis Ridley claims that, on the basis of these vague journal entries, Jeanne was gang-raped by the other servants at Port Praslin. The story gets even more elaborate with the telling – that she fell pregnant and later had a child in Mauritius. It’s almost as if disaster is what automatically befalls women who dare to leave home, to travel to have adventures. They end up raped or dead, or both. Ridley does not consider rape just as an option, but an absolute certainty.

‘Historians of the expeditions who argue that these passages imply only an inspection and not a rape,’ insists Ridley, ‘are projecting onto Baret’s story what they wish had happened, as opposed to what so clearly did.’

It is an accusation, surely, that swings both ways.

Ridley’s enthusiasm for portraying Jeanne’s story as ‘a narrative of a lone, powerless, terrified woman, who was violated emotionally, psychologically and physically’, is also a case of reading what she wants to read, seeing what she wants to see and ignoring the evidence. As a lecturer in literature, Ridley would be well aware of the power of narrative, of the clichés and tropes in the stories we tell. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the stories people told about Jeanne were always ones of the faithful and devoted servant, as if she was some kind of dutiful Sancho Panza, Man Friday or virtuous Pamela.

In the twenty-first century, the servant trope is difficult to sustain. As women have become increasingly disinclined to stay at home and accept domestic servitude, we seem to invent new stories to keep them in their place. We gleefully tell tales about the dangers of travelling alone, the risks of random rapists and serial killers. The dead naked body of Jane Doe fills our bookshelves and television screens with countless variants of the same story, as if women and girls were not at greater risk of being killed in their own homes by their own partners and families than by strangers in the street. The prevalence of such controlling morality tales, the perpetuation of these fears and the absence of stories about the woman who defy them is a tenacious and perplexing feature of human culture.

The presumption of Jeanne’s rape 250 years post hoc has spread across the internet in the last decade and is now ubiquitous. Having been said, it cannot be unsaid. It’s hard to find a popular account of Jeanne Barret that does not mention this as if it were fact. The loyal, faithful, self-sacrificing servant of the nineteenth century has disappeared, replaced by a victim of the male patriarchy. Both stories are clichés and neither is well-supported by the evidence. There’s no denying that women have been oppressed, subjugated and sexually abused for centuries, if not millennia, and that this problem continues today. There are plenty of stories we should tell about this, but surely we don’t need to turn every woman’s story into the same one. Do we really have to keep figuratively burning every Jeanne d’Arc at the stake for her heresy?

No-one can say if Jeanne was raped or not, in New Ireland or elsewhere. There is no evidence that she was, no proof that she wasn’t. But in a society where women were often labelled as promiscuous when they were victims of male sexual violence, Jeanne’s virtue and faithfulness were stressed by every single one of the men who documented her presence – even Vivez when he very clearly seems to have wished it were otherwise.

Rape was punishable by death in the French navy. Failing to declare a pregnancy, too, was illegal – also punishable by death, even if this was rarely enforced. By contrast, allowing a woman on board ship was only punishable by a few weeks’ arrest or a minor fine. And the French, in the navy as elsewhere, were scrupulous administrators of paperwork. I find it difficult to imagine that if the servant of the King’s Naturalist on board a naval vessel had been raped, and/or fallen pregnant, that complaints would not have been lodged, that paperwork would not have been completed, that the perpetrators would not have been punished and that the records would not have been found, or that Jeanne herself, who carried those two pistols in her belt at all times, would not have exacted her own reprisals. At the very least, bitter commentary would surely have slipped into Commerson’s private journals and letters.

And finally, what naval commander could afford to overlook such a serious breach of discipline, when both Bougainville and La Giraudais had explicitly given orders to ensure that she was not to suffer any unpleasantness?

You can read whatever you want into this incident. Perhaps I’m reading what I want into it. Many things happened on this journey for which there is no evidence, but history is not the place to discuss them. Personally, I can see no reason why, in an age where women’s lives were so constrained, where women were denied so much and permitted to achieve so little, this one woman who managed to escape the constraints of her sex to travel the globe should be a victim instead of a hero.

There is no evidence of a rape. There is no evidence of a pregnancy. But it’s clear that Jeanne’s true identity, from here on, must well and truly have been known to everyone.