CHAPTER 3

Intermezzo:

the key ingredient of an ideal diet is you

What’s more (un)healthy, carbohydrates or fat?

If it’s the case that a certain, moderate amount of protein is best for us (not too little, not too much), that inevitably means we can, or even must, tuck in to other kinds of food. Protein usually makes up only about 15 per cent of our calorific intake, so in purely arithmetical terms that leaves 85 per cent of our plate empty. What should we fill it with? Which of the main food groups should make up the difference? Carbohydrates or fat? Which of those is the healthier option?

That sounds like a simple, harmless question. But anyone who asks it should be prepared to face the consequences. It’s like diving into the Amazon River filled with masses of underfed piranhas. There is no question that divides people so aggressively as this, and, depending on how you answer it, you will sooner or later find yourself in one of two camps that are deeply hostile to each other.

The answer used to be clear: eat as many carbohydrates as you can and avoid food that’s high in fat. This is the position of the traditional low-fat faction. For them, eating fat only makes you fat, because it contains more calories per gram than carbohydrates.

Saturated fatty acids also make you ill by increasing the levels of cholesterol in the blood. I’ll take a much closer look at the different kinds of fat later in this book, but, briefly, saturated fats are mainly found in animal products — e.g. meat, sausages, full-fat milk, cheese, butter. These fats do indeed increase blood-cholesterol levels, not least of all the harmful LDL type — but more on that later, too. The cholesterol accumulates in the walls of our arteries (atherosclerosis),1 which increases the risk of coronary infarction (heart attack) or, when the infarction (blockage) happens in the brain, a stroke (brain attack):

Saturated fats → increased cholesterol levels → infarction

Solution: low-fat diet

The low-fat approach still dominates in the media and enjoys the most ‘official’ support, for example from the German Nutrition Society (DGE). The consequence of following a low-fat diet is often that we eat more low-fat carbohydrates in the form of bread, pasta, rice, and potatoes. These are generally considered ‘staple foods’.

Bread, pasta, rice, and potatoes? Sorry, what? To any proponent of the low-carb approach, that sounds like a carefully selected mix of poisons. Low-carb protagonists and other critics of the mainstream position argue as follows: despite the fact that public-health authorities have been warning us urgently since at least the 1980s about the supposed dangers of eating too much fat, and, despite the fact that one low-fat product after the next has taken over our supermarket shelves as a result of those warnings, this has clearly not made us all slimmer and healthier human beings. On the contrary, obesity and diabetes have mushroomed in the same period. It’s no wonder, say the low-carb community, since fat, and not least of all saturated fats, have been unfairly demonised. The real danger lurks elsewhere.

The latest incarnation of the low-carb diet is known as LCHF, which stands for ‘low-carb-high-fat’. In an LCHF diet, all ‘natural’ fats are expressly welcome — including butter, cream, cheese, full-fat milk, and oils such as olive and coconut oil. Margarine, on the other hand, as an oil that has undergone an industrial hardening process to make it artificially spreadable, is rejected.

However, the biggest bad guys for the LCHF camp are the carbs. Top of the blacklist is sugar, closely followed by … bread, pasta, rice, and potatoes. Furthermore, the LCHF diet recommends avoiding any vegetables that grow below the ground rather than above it. ‘Below the ground’ is synonymous with starch, and starch is a highly concentrated carbohydrate made up of long chains of many sugar (glucose) molecules and therefore not good. This rule means potatoes are taboo, as are carrots, beetroot, and parsnips, for example. Vegetables such as lettuce, any kind of cabbage, tomatoes, broccoli, zucchinis (courgettes), and eggplants (aubergines) are preferred.

What exactly does the low-carb community have against carbohydrates? Three arguments tip the scales for them:

Carbohydrates → spikes in blood sugar and insulin levels → fat storage/geriatric diseases

Solution: low-carb diet

The above is merely a rough outline of the two opposing positions to provide a general orientation. The details are so complex that I need to explain them progressively, one at a time. But before I move on to those details, let’s turn briefly to another question: mightn’t we expect this issue to have been resolved, after decades of scientific research have been dedicated to it? Surely it can’t be so difficult to reach a conclusion about which of these two opposing schools of thought is correct, can it? However, the fact is that as soon as you begin to compare the pros and cons of each standpoint, it becomes clear that reaching an unambiguous verdict is extremely difficult, if not completely impossible. Strange, isn’t it? Astonishing, even. That there can be two so diametrically opposed camps, both of which can be supported with thoroughly reasonable arguments and evidence — from biochemical processes to individual case studies and systematically planned experiments. Where does this intractable contradiction come from?

To put it another way: how probable is it that every proponent of the traditional low-fat position has been wrong for decades? Conversely, how likely is it that every one of the very sizeable number of that position’s critics — who include members of prestigious universities and research institutes — is a charlatan or a fool? And if neither of those turn out to be true, then where does our intractable contradiction leave us? If it can’t be resolved, can it at least be mitigated?

This dichotomy plagued me for months. The main aim of The Diet Compass is to compile from all the research findings and various diet concepts an eating plan that unites all the positive health aspects without adhering to any camp or ideology. For a long time, I assumed there would turn out to be one diet plan that would be worthy of being called the ideal diet, an optimum eating strategy that would meet our bodies’ needs better than any other. It would then follow logically that there was an optimum amount of carbohydrates and fat. What’s better for our health, a low-fat-high-carb or a low-carb-high-fat diet? LFHC or LCHF, that is the question!

For some time, those eight, or rather four, letters almost drove me crazy. After agonising back and forth, however, I gradually came to a realisation. A conviction that my basic assumption was wrong. The deeper I delved, the clearer it became that any attempt to define one perfect diet for everyone is not only impossible, but, in fact, counterproductive — especially as far as the relative proportion of carbohydrates and fats is concerned.

There are two reasons for this. Firstly, it turns out that the question whether carbohydrates are unhealthier than fats, or the other way round, is not the crux of the matter. Rather, the crucial issue is the type of carbohydrates or fats. Quality is far more important than quantity. Some carbohydrates and some fats are healthy, others not so much. So the line isn’t between carbohydrates and fats. Such a line is artificial and unproductive. To a certain degree, this overarching principle applies to us all.

Yet there is one important exception: recent research indicates that we vary in the amount of carbohydrate we can tolerate. Some people have a metabolic problem with carbohydrates, and their numbers appear to be growing. Such people suffer from a kind of ‘carbohydrate intolerance’. For them, a reduced-carb, high-fat diet is to be recommended. What’s more, discovering low-carb eating is often a revelation for such people after years of frustration — a kind of liberation. They can satisfy their hunger at last, those extra kilos finally fall away as soon as they change their eating habits, and they rapidly feel much better.

If you happen to be one of those who are intolerant to carbohydrates, then it is not only the quality of the carbs and fats that are important, but also their relative quantities in your diet. In a nutshell, low-carb-high-fat is the best option for you (I examine this particular case in more detail in chapter 5).

For now, let’s stick with the bigger picture. The fact that some people’s bodies only respond favourably to a low-carb diet might cast an interesting light on the long-running dispute between the low-carb and low-fat factions: why is the low-carb movement so stubbornly opposed to the mainstream (low-fat) position, with their opposition always taking on a new guise? The answer is that it is because bread, pasta, rice, and potatoes actually can become a toxic mix. Not for everyone, for sure, and probably not for most of us, in fact (which is why it’s the traditional view). But it is the case for a certain group of people, for some of whom the situation is aggravated by other circumstances. Again, I’ll discuss later in this book what those circumstances are and whether you are one of the people whose bodies can’t tolerate too many carbohydrates. In this chapter, I want to take a slightly closer look at the overall situation and outline how both a high-carb diet and a high-fat diet can be very healthy, in principle. Let’s start with the carbs, before we turn to the fats.

Lots of carbs: from Okinawa to the Adventists

In recent years especially, damning carbohydrates lock, stock, and barrel has almost become a national sport. My advice is to remember the diet of the elderly Okinawans whenever talk turns to ‘bad carbs’. The Okinawans are among the healthiest people in the world — and what do they eat? Mainly carbohydrates! Carbohydrates used to account for no less than 85 per cent of the calories in their diet. Although it has changed over the decades, that proportion is still high today, standing at almost 60 per cent.

In the traditional Okinawan diet, only 6 per cent of the energy came from fats. That figure really bears thinking about: ‘low-fat’ is usually applied to a diet in which the proportion of fat is 30 per cent or less. So to describe the traditional Okinawan diet as ‘low-fat’ would be a massive understatement: it is (or was) a ‘very low-fat’ diet.

And it really doesn’t appear to have done the Okinawans any harm. Indeed, Okinawa islanders of the older generation don’t just live to an unusually great age, they also suffer considerably less from cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and dementia than the likes of us. There are around 50 centenarians in every 100,000 Okinawans — more than twice as many as there are in industrialised countries (Germany currently has ‘only’ 22 centenarians per 100,000 inhabitants).2 In other words, carbohydrates cannot per se be so terribly toxic.

And here comes the big ‘but’: on closer inspection, it turns out that Okinawa is a very special case, which can only be applied in very limited terms to the situation we live in. As mentioned previously, Okinawans used to eat very little overall. Their aversion to overeating goes back to a Confucian teaching called hara hachi bu, which can be loosely translated as ‘eat until you are 80 per cent full’. The Okinawans’ good health and longevity could well be due to this ‘calorie restriction’. That would be my best guess, in view of the fact that dietary restriction is one of the best ways of extending the life span of a wide range of organisms and animal species — yeasts, worms, flies, fish, mice, and even monkeys.3

Ultimately, the crucial factor for the longevity of the traditional Okinawa islanders is simply not known. We don’t have that knowledge. This is compounded by the fact that the Okinawans’ lifestyle and culture are so radically different from our own, not to mention the genetic differences, and it becomes legitimate to ask to what extent they might serve as a realistic model for us. I think they can do so only in a modest way, at least as far as the relative proportions of food from the main food groups is concerned.

The same applies to many other remarkably healthy ethnic groups that have attracted the interest of researchers in recent years, such as the Tsimané. They are hunter-gatherers who live on the banks of a tributary of the Amazon River in Bolivia. Atherosclerosis is virtually unknown among the Tsimané, a fact that’s equally astonishing and encouraging. It could mean that the crucial factor for this leading killer disease is largely self-inflicted, and therefore avoidable. In other words, atherosclerosis is probably not an inevitable consequence of ageing, although that’s usually the explanation we’re given for the condition.

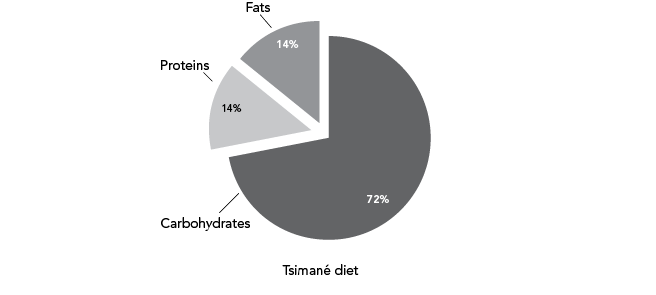

The diet of the Tsimané consists of no less than 72 per cent carbohydrates, while 14 per cent of their calories come from fat, and another 14 per cent from protein. Their diet is predominantly vegetarian. Is it the Tsimané’s diet that protects their hearts from disease? Maybe. Or it could be their lifestyle as a whole. The Tsimané live in simple thatched huts without running water or electricity. Hunting — sometimes still with bows and arrows — can take eight hours or longer and can involve the Tsimané trekking up to 18 kilometres through the rainforest. That means they literally spend all day on their feet, spending less than 10 per cent of the time sitting.4 Therefore, the lesson we might learn from this is not that eating lots of carbohydrates is good for your health, but that eating a natural diet consisting principally of (high-carb) vegetables, combined with lots and lots of physical exercise, is extremely good for your health.

According to Germany’s National Nutrition Survey, carbohydrates account for less than 50 per cent of Germans’ calorific intake (approximately 47 per cent), while fats account for 36 per cent. That means the German diet is much less carb-heavy and more fat-heavy than that of either the Okinawans or the Tsimané.5 This could lead us to conclude that Germans and those from similarly affluent countries should eat less fat and more carbohydrates. And that is precisely the message propagated by the German Nutrition Society (DGE) and other proponents of the low-fat approach. The DGE guidelines state that at least 50 per cent of the calories we ingest should come from carbohydrates.6 And there’s no doubt that this recommendation can lead to a very healthy diet.

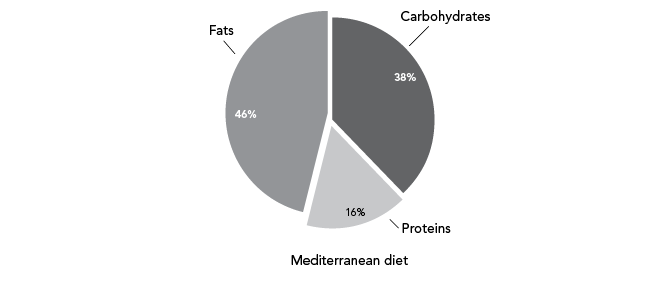

It can, but it doesn’t have to. Firstly, it doesn’t necessarily follow that more carbohydrates make for a healthier diet — it’s no secret that sugar is a carbohydrate and not a beneficial vitamin. Secondly, and more importantly (since the DGE does not, of course, advise eating more sugar, although there are unfortunately some low-fat fans and gurus of veganism7 who play down the dangers of sugar), there are certainly high-fat diets that have repeatedly been shown in studies to be extremely healthy. Incidentally, the best known of these is not only world famous, but also considered by many leading nutrition scientists — including Walter Willett of Harvard University8 — to be the ultimate healthy diet: the so-called Mediterranean diet. Depending on how it’s followed, the proportion of calories in the Mediterranean diet that come from fat can reach 40 per cent or even higher (while carbohydrates typically account for less than 40 per cent).

Since the staple-nutrient fat has been demonised for so long and is still seen by many people as a kind of poison and the quickest way to gain weight, I think it’s worth taking a closer look at the healthy, high-fat Mediterranean diet. The results produced in recent years by many scientific studies of this way of eating show that there is simply no rational basis for our fatphobia. To be clear from the outset: just as it is possible to live very healthily to a very old age on a high-carb diet, it is also possible to do so on a high-fat diet. The following is a graphic summary of main points so far:9

The traditional diet in Okinawa is extremely rich in carbohydrates, extremely poor in fats, and very healthy.

The diet of the Tsimané contains a slightly smaller proportion of carbohydrates and slightly more fat. It is also very healthy.

The diet of the Adventists is still carb-heavy. It contains relatively little fat, but still enough to mean it no longer warrants the designation ‘low-fat diet’. It is also very healthy.

The Mediterranean diet typically contains more fat than carbohydrates. And it is also very healthy.

The high-fat Mediterranean diet: so healthy they had to abandon the experiment early

The Mediterranean diet gets its name, of course, from the fact that it’s based on the traditional eating habits of people who live in that part of Europe — in particular, in southern Italy and Greece, especially on the island of Crete. The name is somewhat misleading as there’s no one, single Mediterranean way of eating. Just to be quite clear: someone visiting a branch of McDonald’s looking out on the port of Genoa cannot claim to be eating ‘Mediterranean food’. What I mean by this is that the modern eating habits of many Mediterraneans do not necessarily count as a Mediterranean diet in the sense that excites so many nutrition scientists.

Okay, that kind of goes without saying, but it actually goes a step further. Even your usual margherita pizza or spaghetti bolognese (which used to be one of my favourite meals) are not dishes that experts would describe as typical examples of food from a Mediterranean diet. Again: for nutrition researchers, pasta is not the be-all and end-all of the Mediterranean diet, despite the fact that we tend to equate Mediterranean food with huge piles of pasta. So you might argue that the term ‘Mediterranean diet’ is not particularly apt. Personally, I think life’s too short to get upset about terminology. I think it’s more important to be clear about what I mean when I talk about the Mediterranean diet in the context of modern nutrition science. So here are the key components of a Mediterranean diet:

You can easily work out your own ‘Mediterranean factor’ with the aid of a short questionnaire that’s used in experiments to test how closely subjects adhere to the Mediterranean way of eating (see fig. 3.1). The more points you get, the more Mediterranean your diet is, in the idealised, nutrition-science sense of the term. The ‘Mediterranean factor’ resulting from this questionnaire is more than just a bit of fun. The higher your result, for example, the lower your risk of developing high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity — and in particular, obesity in the abdominal region.

It’s particularly remarkable that fats play such a significant part in this effect. We see that it is the very foodstuffs that are highest in fat content and which we usually consider fattening that are helpful in losing weight with the Mediterranean diet. Nuts, for example, have been associated in scientific studies with the most reduced risk of abdominal obesity. In other words, regularly snacking on nuts is more likely to help you achieve a flat tummy than not eating nuts at all. And according to such analyses, even olive oil is a ‘slimming food’! (While, conversely, totally fat-free soft drinks are among the most fattening foods — more on that in the coming chapters.)11 Results like these provide initial indications that the fat we eat is not automatically stored as fat by our bodies. Fat doesn’t necessarily make you fat. And for some high-fat foods, such as nuts and olive oil, the opposite is true.

TEST YOUR ‘MEDITERRANEAN FACTOR’

|

Question |

If applicable, add 1 point |

|

Do you use olive oil as your main source of fat when cooking? |

Yes |

|

How much olive oil do you eat per day? |

At least 4 tablespoons |

|

How many portions of vegetables do you eat per day? (1 portion = 200 grams) |

At least 2 (of which at least one is raw vegetables or salad) |

|

How much fruit do you eat per day? |

At least 3 portions |

|

How many portions of red or processed meat do you eat per day? (1 portion = 100 to 150 grams) |

Fewer than 1 |

|

How many portions of butter, margarine, or cream do you eat per day? (1 portion = 12 grams) |

Fewer than 1 |

|

How many soft drinks do you drink per day? |

Fewer than 1 |

|

How much wine do you drink per week? |

At least 7 glasses (of 100 mL, which is about one bottle) |

|

How many portions of pulses (beans, lentils, chickpeas) do you eat per week? (1 portion = 150 grams) |

At least 3 |

|

How many portions of fish do you eat per week? (1 portion = 150 grams) |

At least 3 |

|

How many portions of sweets and confectionaries (cakes, biscuits, etc.) do you eat per week? |

Fewer than 3 |

|

How many portions of nuts do you eat per week? (1 portion = 30 grams) |

At least 3 |

|

Do you prefer white meat, such as chicken or turkey, to red meat, such as burgers and sausages? |

Yes |

|

How many times a week do you eat sofrito (a tomato, onion, garlic, and olive-oil sauce)? |

At least 2 |

Fig. 3.1 This questionnaire is used by researchers to sound out how closely someone adheres to the idealised Mediterranean diet, which has been shown to be extremely healthy in many tests. The more points you scored, the more ‘Mediterranean’ your diet is. The risk of a serious cardiovascular event (stroke, heart attack) is more than 50 per cent lower for those who score 10 points or more, compared to those who score 7 or less. The three aspects of this diet that contribute most to lowering that risk are (in order of significance): vegetables, nuts, and wine.12

All of these results stem from purely observational studies, which do not take into account cause-and-effect relationships. For example, they can’t give us information on whether nuts and olive oil are the actual cause of the beneficial effect recorded. However, there have now been several experiments that provide impressive confirmation of the observations made.

A few years ago, a team of Spanish researchers carried out a large-scale study on the effects of the Mediterranean diet with almost 7,500 test subjects. Half the subjects were instructed to follow a high-fat Mediterranean diet closely. The other half were the control group, and were called on to pursue a diet less rich in fat.

All the test subjects had an increased risk of a cardiovascular-disease event, and the researchers wanted to find out whether that risk could best be reduced by following a high-fat or a low-fat diet. ‘What a question!’ you might be saying right now, shaking your head in disbelief. Of course anyone who wants to protect their heart should avoid fat as much as possible.

To help the Mediterranean-diet group keep up their abundant consumption of fat, half of that group were given a free litre of olive oil every week to use as they wished. The other half were given free supplies of nuts (a 30 gram per day portion of mixed walnuts, hazelnuts, and almonds). In this way, the Mediterranean half of the subjects were subdivided into two groups — an olive-oil group and a nuts group. The low-fat half of the subjects were not given any free food supplies.

The results of the experiment were dramatic. It went so spectacularly well for the subjects who followed the Mediterranean diet and, by comparison, so badly for the control group, that the ethical review board recommended abandoning the experiment after a few years. In their opinion, the ongoing results showed it was no longer justifiable to continue to deny the control group a beneficial high-fat diet.

In particular, the Mediterranean diet drastically reduced the risk — relative to the control group — of suffering a stroke. It went down by 33 per cent in the olive-oil group and by 46 per cent for the group eating extra portions of nuts. Follow-up analyses also revealed that those who scored 8 or 9 points on the Mediterranean-factor questionnaire saw their risk of a severe cardiovascular event such as a stroke or a heart attack reduced by 28 per cent compared to those who scored 7 points or less. For those who scored between 10 and the maximum 14 points, that risk was reduced by no less than 53 per cent.13 In short: the more Mediterranean your diet is, the better it is for your heart.

The Mediterranean diet had already gained a certain popularity thanks to earlier positive research results, but, when the Spanish study was published in the renowned medical journal The New England Journal of Medicine in 2013,14 it became popular around the world (in fact, years earlier, a similar experiment in France had had to be discontinued early due to similarly spectacular results15).

And reports on the beneficial effects of the Mediterranean diet continue to appear regularly. Recent research, for example, shows a Mediterranean diet is associated with a measurable reduction in brain atrophy in old age.16 For some people, such a diet has an astoundingly beneficial effect in combating depression.17

It’s not only the Mediterranean diet itself that has risen in popularity; fat is also experiencing a real comeback thanks to these and many more positive research results. You might say low-fat diets are becoming increasingly passé, while fat has become increasingly in vogue in recent years. And understandably so! Mediterranean food is not only healthy, but also delicious, as I’m sure many people will agree.

This is due in no small part to the olive oil that features so predominantly in the Mediterranean diet, and not only because it tastes good itself. Olive oil also enhances the flavour of any other ingredients. Have you ever tried to clean oil or fat from a frying pan using only a kitchen sponge — without detergent? With water that’s only lukewarm? Everybody knows fat is sticky; it smears and is hard to remove. And the same is true of its behaviour in your mouth. Fat gives food a pleasant consistency, and sticks flavours to your palate, as it were. It adheres to the inside of your mouth as it does to a pan, which allows it to fully develop its aroma rather than being washed down with the food immediately. So fat is a kind of natural flavour enhancer. Great!

Still: all this enthusiasm for fat should not belie the fact that even the mostly high-fat Mediterranean diet (there are also lower-fat versions) is ‘only’ one of the ways to eat more healthily. Incidentally, in the Spanish experiment, the proportion of fat in the diet of the Mediterranean group was 41 per cent, which may be high, but that figure for the control group, who had been asked to eat less fat, was still a relatively high 37 per cent. The fact that there was such a marked difference in the groups’ risk of suffering a stroke shows once again that it is not the absolute amount of fat eaten that’s important, but the overall character of the diet followed. In concrete terms: I don’t believe that it is simply the high-fat nature of the Mediterranean diet that makes it so healthy — in the same way that, conversely, it is not the huge amount of carbohydrates in their traditional diets that’s responsible for the excellent health and longevity of the Okinawans or the Tsimané. It’s far more likely that the secret of healthy-eating cultures, from the islands of Okinawa to the rainforests of Bolivia and certain parts of the Mediterranean, lies in the fact that all those cultures eat a diet of real, natural food rather than industrially produced fast food. Their diet is sourced straight from nature and mainly, although not exclusively, from plants.18

Why it’s so important that you shape your own diet

Most diet books side with a particular nutritional approach, supporting some ‘program’, whether it be vegetarianism, veganism, low-fat, low-carb, Paleo, pineapples, or some variation on the Mediterranean diet. They then proceed to ‘prove’, on the basis of some carefully selected studies, why their program is better than all the others.

On the one hand, such an extremely limited and partisan view can make life easier. But on the other, it means forcing people completely arbitrarily to follow one program, one doctrine of salvation. If you eat exactly like this (i.e. like Tsimané hunter, or an Okinawan islander, or like X or Y from some mountainous Mediterranean region), you will lose weight and live a long and healthy life. Yet there is no objective reason to follow any particular set of recommendations, since there are demonstrably many dietary approaches that can help you live long and stay healthy.

So we are justified in approaching this issue with a more open mind, and that strikes me as eminently sensible, since everyone’s body is different. Rather than desperately forcing a diet on our bodies, we should be listening to them, feeling their responses, and experimenting with different ways of eating, irrespective of any dogmas and ideologies, to find out how our bodies react to various types of diet. This is the best way to find out what — within the bounds of the recommendable — is right for you. Slavishly following a specific diet usually only leads to abandoning it. There’s no such thing as the ideal diet, even though most diet gurus and even ‘official’ institutions often insinuate that there is.

At first, the realisation that we are all different appears to make the task of finding a healthy diet more complicated. There’s no one set of strict recommendations that are valid for everyone under all circumstances. At the same time, it means you have more options for shaping your own diet. Don’t become a slave to any particular diet program by listening to some outside authority more than to your own body. Always bear in mind: your body is an authority, too.

What typically happens when we go on a diet? For a while, we try to keep it up, in defiance of the signals from our body — only to give up at some point, in frustration or disgust. No wonder! That diet is an alien program that we try to impose on our bodies. It seems to me that both the initial success and the prompt failure of many diets is inevitable due to their inflexible, pared-down nature. At the very beginning, they work because we’re highly motivated — but also, and equally importantly, because the unusual fare we’re eating simply goes against the grain. We don’t really know what we should cook, the recipes aren’t tasty, the food gives us wind, the food makes us feel sick … We eat less as a result and that of course leads to weight loss. But then sooner or later, we abandon the diet for precisely the same reasons. (The only time when this isn’t the case is when we accidentally stumble upon a diet plan that happens to suit us perfectly.)

A good friend of mine tells me that every time she consumes too much olive oil and nuts (at my house), she has a sleepless night, plagued by a feeling that she is ‘blocked up’ inside. Clearly, a low-fat diet would be easier on her digestion. Forcing her onto a high-fat, low-carb diet would just be counterproductive.

As we know, the best criterion for a successful diet is that we can stay on it, which can only be the case in the long term if it doesn’t feel too much like we have to ‘endure’ the diet. Thus, although it appears to complicate the matter, we can almost consider it a stroke of luck that there’s no such thing as one route to diet success that is paved with gold, but rather many different pathways. After all, what it means is that you can largely put together your own diet plan, one that suits your own body. And that, in turn, makes it more likely that you will then stick to it.

As we have seen, there are limitations to the amount we can manipulate our protein intake. As far as carbohydrate and fat are concerned, there’s more room to manoeuvre, at least in their proportions relative to each other, for the simple reason that those relative amounts are not important for most of us. What is more important is that we choose the healthy carbohydrates and fats. Recognising which carbohydrates and fats they are, and which we should be avoiding, is the subject of the following chapters. Let’s start by looking at carbohydrates, and straightaway let’s examine the most seductive, but also the most pernicious of the carbohydrates: sugar.