And I said to them, “You see the trouble that we are in, how Jerusalem lies desolate and her gates have burned with fire. Come, let us build the wall of Jerusalem, so that we are no longer a reproach.”

—NEHEMIAH 2:17

Guthrum’s sudden conversion to the Christianity of the Anglo-Saxons and the taking of the Saxon name Æthelstan may have been difficult to believe. Was the Viking king’s sudden embracing of the Christian faith a genuine and heartfelt repentance of his pagan past? Or was it a pragmatic decision, cunningly chosen to exploit the weakness and gullibility of Alfred’s faith? The scholarly method tends to veer toward the more cynical interpretation, presupposing that only the basest motivations lay behind every decision: Guthrum must have received baptism because it bought him time to remove his troops peacefully, only to strike again at a later date. Or possibly, Guthrum had resigned himself to the fact that Alfred would remain in control of Wessex, and the conquered Viking saw that as a godson to the only reigning Saxon king he would be woven into the web of Saxon nobles and given opportunities to increase his own power and wealth.

Jesus described in a parable the problem of the short-lived conversion, likening the temporary convert to seed thrown onto rocky soil where its roots could not grow deep (Matthew 13:3–9). The seed sprouts at first, but with such shallow roots and impeded by the rocky soil, it is unable to endure the heat of the afternoon sun and quickly withers and shrivels away. Other seed is eaten up immediately by the birds or choked to death by crowding thorns. But some seed falls on good soil and endures throughout the growing season, bringing in a bountiful harvest.

The true convert, Jesus later explained, was like this enduring seed. His faith persevered to the end of his fruitful life. So what kind of seed was Æthelstan? Was this new faith to be quickly choked out by the cares of the world? Would it lack perseverance? Or would his profession of faith endure to the end? With great concern, Alfred waited for the answer to this question.

The arrival of a fresh band of plunder-eager Vikings provided the first test of Æthelstan’s sincerity. In the late autumn of 878, this new Danish army camped at Fullham, on the northern bank of the Thames, just west of London. Then, having settled in for the winter, the Fullham Vikings sent word to Æthelstan in Cirencester, seeking to form a mutually profitable alliance with the Viking by which they might plunder the kingdom of Wessex.

In Winchester, Alfred received regular messages from his thegns about the movements of this new band of Vikings and of Æthelstan, who was still camped at Cirencester, perched menacingly on Alfred’s northern border. From the intelligence he was able to gather, it seemed likely he would soon be facing his godson in battle once more, reinforced with a fresh supply of Danish warriors. Then, doubling his suspicions, one afternoon shortly after the Vikings made their camp on the bank of the Thames, all of Wessex fell under a shadow of terrible darkness as a shield as black as death slowly swallowed the sun and all its brightness and heat.

This solar eclipse was reported by a number of contemporary Anglo-Saxon historians. And though it was understood by Alfred and all the thegns of his court that the eclipse of the sun was always a significant portent, it was unclear just how this particular omen should be interpreted. Did it signal the apostasy of Æthelstan and one more devastating Danish assault on the nation of Wessex? Or was it a confirmation that Alfred’s victory at Edington had made his rule over Wessex sure and unequivocal?

The answer to these questions was soon made clear. Æthelstan refused the invitation from the Vikings at Fullham and sent their emissaries away from his court empty-handed. The Vikings of Fullham, seeing there was no chance of an alliance with Æthelstan and realizing the resolve of Alfred and his battle-hardened men, abandoned their hopes for easy Saxon plunder and at the end of winter climbed back into their ships to sail for the European continent where resistance to plundering bands was less resolute.

Sailing away in 879, these Vikings established a base in Ghent and spent the next several years slaughtering and plundering the surrounding monasteries and convents. Æthelstan, however, stayed true to the vows of his baptism and pulled his own troops away from the northern border of Wessex, leaving Cirencester to march back to East Anglia, where he settled into life as a Christian king, ruling over the people of East Anglia.

Though it may be difficult to be entirely rid of suspicions about the sincerity of Æthelstan’s faith, the evidence indicates that Æthelstan was the good seed, fallen on fertile soil and yielding a bountiful harvest. He refused to join the Viking raiders in their planned attack on Wessex, and throughout the years, he maintained the peace between himself and Alfred, entering into several treaties with the Wessex king. After his baptism, he never gave reason to believe that he was anything other than a sincere Christian.

When the East Anglian king later minted his own coinage, it was his Christian name—Æthelstan—that appeared on every coin, rather than his former Viking name, Guthrum. During the following decades, however, the coin to become the most popular coin in all of Danish East Anglia was the Saint Edmund penny, a silver coin that had been minted to commemorate the martyrdom of Edmund, the Christian king of East Anglia who had been struck down by the pagan chieftains Ubbe and Ivar, Guthrum’s former comrades. What a tremendous irony that within two decades of Edmund’s martyrdom, his murderers would be converted to his faith and would begin issuing commemorative coins to remember his death.

Ten years later, when King Æthelstan died, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded his death and described him as the northern king, whose baptismal name was Æthelstan, the godson of Alfred. No mention was made of his life as a Viking or his years of waging war against Wessex. He was simply Alfred’s godson.

The departure of the Viking force that had been encamped at Fullham, together with the new alliance formed with Æthelstan, left Alfred and his weary kingdom with an unexpected respite from military campaigns. Alfred understood that this peace would only be temporary, since other Northmen seeking plunder would inevitably come to try their luck at despoiling the wealth of Wessex. Therefore, this respite from the Viking-inflicted bloodshed could not be spent in peaceful rest and relaxation, feasting and drinking in the mead hall, and enjoying the intensely refreshing English summer. Rather, this was a surprising lull in the storm that offered a brief, but much needed, chance to rethink the organization of the defenses of Wessex and to better prepare the Saxon military for fighting off future invasions. If Alfred was to hold together the last Anglo-Saxon nation against future Viking onslaughts, then the Wessex military needed to be restructured to better respond to the Danish threat, and this moment of peace offered the king of Wessex time to accomplish just that.

The necessary military reforms required Alfred to give some thought to the strengths of the Viking armies and how they had managed to exploit the weaknesses of the defenses of Wessex. It was now clear that the real strength of the Vikings was not necessarily their ferocity in battle. The Wessex army had regularly been able to hold their shieldwall while facing down their Viking enemies. The problem the Saxons repeatedly encountered was the swiftness and cunning of the Viking armies.

Between the inexhaustible network of rivers criss-crossing the British countryside—which the Danes were able to exploit with their shallow draft boats and expert seamanship—and the still-functional Roman road system that afforded great mobility to mounted Danish troops, the Vikings were able to move at a speed that no Saxon fyrd could match. They struck and plundered the easily gained wealth of undefended towns and then moved on long before any military aid could be sent to defend the victims of the raid. Then, on the rare occasions when the Saxon fyrds were able to respond quickly enough to actually corner the Viking raiders, the Danes merely fortified whatever town had last fallen victim to them and waited for the Saxons to tire of the siege and resign themselves to paying the danegeld.

If Wessex was to resist future Viking assaults, then it was imperative that Alfred construct a defensive system capable of countering the incredibly swift mobility of the Viking troops, a system that would rob the Danes of the ability to wait out a protracted siege only to be rewarded with a payment of danegeld.

The king had always maintained a small force of professional soldiers attached to his court who were capable of responding quickly to military threats. These were the men who dwelt in Alfred’s hall, drinking his mead and pledging him their blades. They were a stouthearted troop—faithful, intrepid, and sword-savvy. But this force of loyal thegns numbered less than two hundred men and thus was far too small to face the larger raiding armies of more than one thousand Northmen, which had begun to plague England during Alfred’s reign.

The larger voluntary shire fyrds, which formed the bulk of Wessex’s military might, were drawn from the landowning noblemen and other freemen of Wessex. They could be a fierce force when they stood defending the farms, homesteads, and villages of their native land, but they could be painfully slow to mobilize, often requiring weeks to wrap up their obligations at home and finally prepare themselves for battle. When they were finally mobilized, the work that had been left undone on the farms and in the shops back at home, as well as the families that had been left unguarded, weighed heavily on their minds. Thus their loyalty to the ongoing military campaign would frequently begin to wane when the campaign dragged on indefinitely during the siege of a Viking fortification and kept them from fulfilling their duties at home.

Rectifying this problem would require that Alfred effect a massive reform of the Wessex military. To quickly field an army large enough to fend off the Viking armies, Alfred could no longer rely on the sluggish response of the traditional fyrd. Instead, he would need to maintain a large standing army of soldiers skilled in war craft who were ready to respond to an invading army at a moment’s notice.

Alfred divided the entire Wessex fyrd into halves and insisted that each half take turns mobilizing and preparing for combat. This left each town with half of their combat-eligible noblemen and freemen overseeing the work in the fields and other necessary chores, while the other half provided the necessary military service, waiting battle-ready to respond to any possible Viking attacks. Although this put a heavy strain on the local economies by permanently absenting half of the landowners, it guaranteed that, even in moments of national emergency, no more than half of the leading men would be called away for fyrd service. Since the rotation between working at home and standing ready in the fyrd was scheduled and predictable, the disruption of the work schedule was much more easily mitigated.

The men in this new standing army were divided into two sections. One portion became a highly mobile army, camped in the fields of Wessex and waiting for news of any possible threat to the Saxon peace. The men of this army were required to provide their own horses, as well as enough food for sixty days, giving this large army the ability to travel the length of the nation in several days and to wage war at a moment’s notice. The other portion of the standing army was assigned to guard a collection of fortified cities and towns spaced evenly across the breadth of Wessex. This division of the military provided Alfred with a highly mobile offensive force, which could travel quickly to confront any intruding threat, as well as a defensive garrison guarding each of the fortified cities. Thus Alfred ensured that no matter where he moved his mobile force, the cities of Wessex were protected.

By keeping a defensive force in these cities, Alfred robbed wandering Viking armies of the ability to easily seize an unprotected city and fortify it against the Saxon army. Additionally, the knowledge that there was another army guarding the families and farms left behind gave peace of mind to the soldiers serving in the mobile army and the ability to more resolutely pursue their enemies far and wide. And, since the military also acted as the Anglo-Saxon “police force,” the presence of an organized force throughout the nation significantly improved the law and order of the cities, towns, and villages of Wessex.

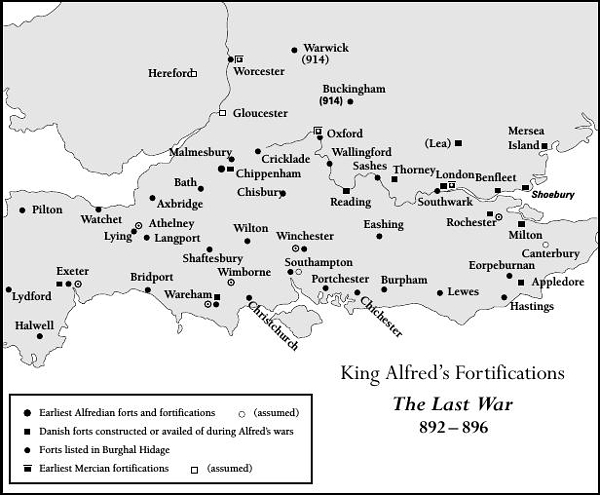

Alfred’s innovations in organizing the garrisons that would defend the fortified cities of Wessex constitute probably the greatest administrative accomplishment of his reign. First, the king carefully selected thirty Wessex cities to receive garrison forces from the rotating fyrd. Each of these cities was positioned within around twenty miles (or one day’s march) of one another, forming a network of fortified cities that covered the extent of Wessex.

© MARK ROSS/SURFACEWORKS

Some of these cities, such as Bath, Chichester, Hastings, and Winchester, had long histories that reached back to the Roman occupation of Britain. The unusually regular grids of the ancient streets provided a helpful footing upon which Alfred built, exploiting the firm foundations the Roman ruins offered as well as maintaining the efficiency of the older city layouts. Some cities, like Cissanbyrig, Brydian, and Halwell, were built on the ancient Iron Age hill-forts taking advantage of the defenses offered by their lofty heights and still-standing earthwork walls. Other city-fortresses were built as entirely new constructions, where no significant settlement had previously stood. Each city’s location was carefully chosen to ensure that all the major passages through Wessex, both by road and by river, were guarded by not just one but several of Alfred’s new fortresses. Roads connecting these cities were constructed and maintained to ensure that each garrison could swiftly send news, supplies, or reinforcements to neighboring garrisons, allowing the nation as a whole to respond swiftly to any attempted invasion.

Next, Alfred ordered that each of these cities be fortified with a defensive wall capable of withstanding an assault by Danish attackers. The construction of these defenses transformed a selected city into a burh, the Anglo-Saxon word for a fortified dwelling. Many English towns still carry the remnants of this designation in their names; the suffixes -bourgh or -bury indicate their former classification as an ancient burh.

Though the Romans and the Iron Age tribes who inhabited southern Britain many centuries before the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons had often fortified their cities with earthwork defenses of moats and dykes, as well as wooden and occasionally stone walls, the defenses erected in Wessex during Alfred’s reign were the first defensive fortifications built in Wessex throughout the Anglo-Saxon era. A deep moat and a newly constructed wall encircling the city defended each of the thirty burhs.

Where possible, the Saxons used ancient Roman or Iron Age moats and walls, rebuilding the ancient stone walls and deepening the defensive ditches. But many of the new burhs lacked any preexisting fortifications and required that the entire ditch and wall structure be built fresh. In these cases, the Saxons opted primarily for the swifter method of building with wood, rather than stone. The burh walls included a fighting platform circling the inside of the palisade, from which the defenders could fire arrows or even stones on an attacking force. Many of the walls were also equipped with defensive towers and gatehouses.

After the walls were constructed, Alfred devised a unique method of calculating the troops to be stationed within each burh at any given time. The wall of each burh was measured in “poles,” an Anglo-Saxon unit of length that corresponded to approximately five and a half yards. One pole of fortified wall required four men to properly defend it. Each of these men represented one “hide” of the surrounding farmland. A hide covered approximately 120 acres. Thus, it was considered reasonable to expect that 120 acres’ worth of farmland, or one Anglo-Saxon hide, could supply one man, suited for combat, to defend the fortified walls of the burh. This created a convenient formula for coordinating the size of a burh’s wall with the number of men expected to defend that wall, as well as the amount of surrounding farmland necessary to support such a force.

A manuscript dating from shortly after Alfred’s reign, known as the Burghal Hideage, preserves the total hides prescribed for each of the Wessex burhs. As many of the old city walls of Alfred’s burhs have been discovered and measured out, it is shocking how closely these measurements, when run through the formula described above, correspond to the number of hides assigned in the Burghal Hideage. For instance, the Saxon walls of Alfred’s capital city, Winchester, have been measured recently at 3,318 yards. The Burghal Hideage assigned 2,400 hides to the city, requiring that the city wall be defended by the same number of soldiers. At four men per pole, this suggests a total wall length of 600 poles. If each pole stood for 5.5 yards, then the walled perimeter would need to measure a total of 3,300 yards. When compared to the 3,318-yard measurement calculated by modern archaeologists, the numbers listed in the Burghal Hideage are remarkably close.

The much smaller burh of Porchester offers a similar testimony. The archaeological evidence suggests a measurement of 697 yards for the original perimeter of the ancient walls. The Burghal Hideage assigned 500 hides to Portchester, or 500 men for the burh’s defenses. These men could guard 125 poles of city wall, or 687.5 yards.

Alfred set about reworking the network of roads and public places inside the walls with an eye toward ensuring that the burhs would be well prepared to respond swiftly and efficiently to the unpredictable attacks of a besieging army. The king took his inspiration for these new city plans from the pattern used by ancient Roman camps, a pattern still apparent in the road layout of many of the Saxon cities with a Roman history.

Each burh was equipped with one wide street that ran across the diameter of the city, the “high” street, which allowed for the quick movement of troops from one side of the city to the other in order to respond swiftly to the changing tactics of the attacking army. Smaller streets were constructed running parallel or at right angles to the high street, offering quick access to each segment of the wall. Another street was built along the perimeter of the city wall.

This network of roads ensured that a commander could quickly reposition his troops along the city wall to maintain a wall that was properly fortified at all the key points. And though Alfred’s thoughts were all of gory battles and bitter sieges when he conceived this layout, the efficiency of his new system became more evident in the mundane daily tasks than it did in any particular combat engagement. It was in the everyday routine of gathering at the carefully planned marketplace or in the weekly habit of walking to Sunday morning worship in the burh minster, that the sensible road pattern became evident. Alfred’s layouts are still used in numerous cities, testifying to the efficiency of his plans.

Much like Alfred’s new street layouts, the system of defensive burhs, described in the Burghal Hideage, was first conceived as a military innovation. But after it had been implemented, it was discovered that this new system radically improved the efficiency with which the king could administrate his kingdom. The network of burhs and the roads that connected them provided travelers and traders the ability to move across Wessex, stopping every night at a walled and garrisoned burh where peace and safety could be guaranteed.

With the safety afforded by the defenses of the burhs, the surrounding areas naturally gravitated toward bringing their produce and wares to the well-protected and well-governed markets. In later generations, kings of Wessex required that all trade occur within one of the designated burh markets, where the king’s reeves could ensure that proper taxes were paid to the crown on all sales. An alternative Anglo-Saxon word for burh was tun, a term that also referred to a fortified or walled settlement. To this day, an English town, or tun, must feature a town marketplace in order to qualify as a “town.” Without this marketplace, it can only be considered a “village.” (After a town has a cathedral, it has earned the distinction of “city.”)

Under Alfred and the protection that the Burghal Hideage ensured, trade and industry began to thrive in Wessex. Seeing the importance of this element of the economy, Alfred also undertook a major renovation of the Saxon currency. When he came to power, only two mints could be found in the nations of the Saxons, one in London and the other in Canterbury. And these two mints produced an extremely crude coin, boasting a severely debased silver content of 20 percent. A thriving industry of trade would require that these deficiencies be fixed. Soon Alfred was giving his attention to these problems.

By the time of Alfred’s death, the number of mints under the control of the Wessex crown had more than quadrupled. The new silver pennies that Alfred had ordered to be produced were almost pure silver and, even with this much higher degree of purity, still significantly outweighed the previous coinage. In order to mint these new silver pennies, four of the earlier pennies needed to be melted down to provide enough silver for one new penny. The cost was substantial, but the king believed that a restored confidence in the currency would attract the attention of Europe’s traders and eventually would bring a much greater amount of wealth to the nation.

In addition to this penny, Alfred also introduced the half-penny to the English currency. This smaller coin gave merchants the ability to more conveniently sell smaller items. Altogether, Alfred’s innovations had a tremendous impact on the economy of Wessex, catching the attention of merchants throughout Europe who were drawn to the wealth of the newly thriving English nation.

Although the years following Alfred’s victory over Guthrum were characterized by peace within the borders of Wessex, this was only relative to the earlier years of constant Viking occupation. Alfred still had to contend with regular raiding parties of freebooting Danes striking quickly along the coasts and rivers of the Anglo-Saxons, searching for easy plunder. In the year 882, the king received word of one such fleet of Vikings sailing off the coast of Wessex, hunting for easy spoils. Alfred moved quickly to intercept the Viking naval force and engage the invading pirates in ship-to-ship combat.

The Saxon sailors, led by Alfred, still fighting like a wild boar, overtook four Danish boats. They boarded the Viking vessels and set to work with axe and sword, hewing and slashing their way through the Danish fleet. The crews of the first two Viking ships were entirely slaughtered within minutes. Then, as the bloodied but still battle-hungry Saxons spilled into the hull of the next ship, cutting their way on board, the Vikings quickly lost their stomach for the fight. They surrendered and begged for mercy from Alfred, as the historian records, “on bended knee.”

It is interesting that several years after wresting his great victory from Guthrum and establishing peace throughout Wessex, Alfred could still be found personally commanding these smaller combat missions. Though the king was not present for each and every military engagement fought by the Wessex troops, Alfred, until his death, regularly took his sword, shield, and spear into battle, standing shoulder to shoulder in the shieldwall with his countrymen. In the Anglo-Saxon world, combat was the duty of the ruling class; and the king, his thegns, the noblemen, and other rulers of the English people always filled the ranks of the Wessex shieldwall.

Thus, it was the landed class, not the peasants or slaves, who responded to the summons of the fyrd and were expected to die on the battlefield. Though this system may have had its faults, when compared to modern societies where liberty has made great advances against this class system, there remains something about the Anglo-Saxon mentality that was nobler than the governing practices of modern nations. In Alfred’s day, no man could order another into combat to face a gory death in battle if he wasn’t prepared to stand next to him in that same perilous fight. The image of a king ordering his troops to battle while he sat luxuriously pavilioned far from the place of slaughter was the innovation of a much later age and inconceivable to the Anglo-Saxon mind.

In the year 885, Alfred’s many innovations for the defenses of his territories were put to the test. The Danish army, who had earlier camped at Fullham near London and had tested the sincerity of Æthelstan’s baptismal vows, suddenly returned to Wessex hoping to find that several years of peace from Viking raids would have caused the Anglo-Saxons to grow complacent, lax, and vulnerable. This particular raiding army had spent the intervening seven years between their departure from England and their sudden return pillaging the abbeys, priories, and monasteries of northern Europe.

Alfred had actually carefully followed their gruesome career throughout the Franks’ river systems and knew full well of their bloody attack on the ancient monastery of Saint Bertin in West Francia; their progress into Flanders where they forced the people of Ghent to shelter them through the winter; their seizing of horses for their entire force, making their raiding army a mounted troop; their ravaging up the river Oise to Rheims; their attack on the convent of Condé, where the nuns were forced at sword point to provide for their Viking guests for an entire year; their slaughter up and down the rivers Lys, Scheldt, Meuse, Rhine, Moselle, and finally the Somme. And Alfred heard how this particular force had been rewarded for their theft and murder with repeated payments of the danegeld by the Christian rulers in Europe, men like Charles the Fat and Carloman. Then, in the early winter months of 885, Alfred received the ominous message that this army had divided its forces into two, one half choosing to push deeper into East Francia, while the other half returned to England expecting to be rewarded with a tremendous harvest of plunder in those fields that had been left fallow for so long.

By the time the Britain-bound portion of the Viking fleet landed on the shores of Kent, the English winter was well under way. For the last several years, the Danish policy had been to choose a strategic wintering point, a well-provisioned and poorly defended site, which could be overthrown quickly, held throughout the winter, drained of its wealth and stores, and then abandoned in spring as the river waters surged and other potential victims beckoned.

Their arrival on the shores of England late into the season put the Danes significantly behind schedule, so they wasted little time in selecting their target and striking swiftly. The Viking army chose the city of Rochester, a former Roman settlement sitting on the banks of the river Medway a short distance from the river mouth, where the waters mingle with the Thames in the Thames estuary before flowing into the North Sea.

At the beginning of the seventh century, Rochester had been converted to the Christian faith by the missionary Justus, who had been sent to the city by the newly arrived Augustine of Canterbury. As a result of Justus’s efforts, England’s second oldest cathedral was soon built in Rochester, bringing to the ancient city, over the following centuries, all the wealth such an eminent cathedral might attract. This meant that the city of Rochester was blessed with two of the Vikings’ favorite features—a navigable river and a wealthy church.

Although the city of Rochester sat in Kent and was therefore not included in Alfred’s plans for the reconstruction of the defenses of Wessex, the subkingdoms Alfred ruled—Kent, Essex, and Sussex—had all undergone similar programs of reform. Thus the city walls of Rochester had been quite recently refortified to ensure they were constructed to provide the same sort of protection offered in any of the burhs of Wessex. Additionally, the nobles and landowners had organized a garrisoned fighting force equivalent to the stipulations of the Burghal Hideage, a force sufficient to ensure that the newly constructed walls were well defended. For the Vikings, the strength of Rochester would prove to be astonishing.

It would seem that the time elapsed from the moment the dreaded Viking longboats came into view, their dragon-carved prows slicing through the foamy waters of the Thames estuary and then turning to sail up the mouth of the Medway, until the pillaging Danes spilled out of their ships to charge the city would have left little time for a warning to have traveled through enough of the surrounding region to gather any sort of significant fighting force within the city walls.

And so when the Viking horde charged the gates of Rochester splitting the air with their gore-hungry screams, they fully expected to spend little more than a moment hewing through the city’s defenses, leaving the rest of their afternoon free for despoiling the city and the surrounding countryside. That the gates had been bolted against them was not a great surprise to the attacking Danes. But when they drew near the walls to begin smashing down the massive city doors, they were astonished to discover that the many fighting platforms situated along the towering city walls were manned by a substantial contingent of battle-ready Kentish men who eagerly greeted the startled Vikings with a shower of arrows, spears, and rocks.

The initial chaos of the desperate flight from the walls of Rochester, accompanied by the terrifying chorus of shrieks and howls of those who had fallen in the artillery-inflicted carnage, suggested for a brief moment that the Viking force would fall into a total and easily conquered pandemonium. But the disciplined and battle-savvy Danes quickly regained their composure and regrouped just beyond the range of the Kentish archery.

The Viking chieftains were resilient and able to reassess a situation and quickly change their tactics to suit the ever-shifting challenges they faced on the battlefield. Seeing that a direct assault on the walls of Rochester was likely to cost the lives of a great number of Vikings, the Danes resigned themselves to a prolonged siege. Confident in their ability to outlast whatever provisions the men of Kent had hoarded within the city walls, the Danes settled in to wait until the hunger pains of Rochester drove the men to accept the terms of the Northmen—to pay the danegeld.

Having been startled once by the Saxon’s strength, however, the Northmen decided to ensure that their siege was conducted from the safety of a properly fortified position. Soon the Danes began digging a circle of ditch and dike earthwork defenses, constructing a carefully barricaded camp just beyond the gates of Rochester. As the excavation began, another contingent of the Vikings searched out the nearest pastures to find forage for the multitude of horses the Viking troops had brought with them from Normandy in the hopes of using their mounts to wander far and wide from the Kentish river systems. During the following days, the Danes mounted a series of attacks against the defenses of Rochester in the hopes of finding some weakness in the Kentish fortress, some chink in the Saxon armor. But they found none and were driven back from Rochester’s walls on every occasion. Still it seemed that it would only be a matter of time before the besieged city’s determination flagged and the danegeld would ultimately be surrendered.

Although the Viking commanders expected that a shire fyrd would eventually be mustered to contend with them, it was assumed that the gathering of the fyrd would take some time and that by the time the Saxon army arrived, the earthwork fortress would provide more than enough protection to the Danish army. Whatever help Rochester might receive, the Vikings were confident that the siege of the city would continue regardless.

To the stupefying horror of the Vikings, however, only a few days after the raiding army beached its longboats on the banks of the Medway, they received word that an enormous throng of Saxon soldiers was swiftly approaching on horseback. Hardly had the message been brought to the ears of the Viking commanders than the approaching army crested the horizon, innumerable and riding hard, rushing to relieve the besieged city. Not only was this army much larger than expected (being the newly formed standing army of Wessex, rather than the traditional ad hoc shire fyrd), but the ranks of this new force were filled with Saxon men who had spent months training and preparing specifically for a battle such as this. Resolute and battle-hungry, the Wessex forces galloped, with the king of Wessex himself, King Alfred, riding in the vanguard.

The Northmen were thunderstruck. Their typical cool-headed composure evaporated, and they were overwhelmed by a desperate terror and a desire to be as far away from the Anglo-Saxon army as possible. The idea of forming a shieldwall to face Alfred was unthinkable. But the chance of successfully defending the only partially constructed earthwork fortification was equally hopeless. The only attractive option to any of the Viking minds was a dash for safety. The fortress was abandoned. The horses brought across the sea from Europe were left behind. The many Flemish, Frankish, and Anglo-Saxon captives, whom the Vikings had been collecting with the plans of placing them on the lucrative slave market, were all abandoned. In an instant, everything was left behind in one desperate sprint to the Viking longboats.

In the bedlam of the hasty retreat, the Danish army was divided in half. One half managed to reach the beached ships ahead of the advancing Saxons and was able to sail safely down the Medway into the Thames estuary; and without even looking back, they crossed the channel and returned to Europe. The remaining troop of Vikings, overtaken by the cavalry of Wessex, threw themselves on Alfred’s mercy, hoping the king would be willing to offer them some terms of peace.

Fortunately for this band of stranded Danes, the king was prepared to be compassionate and allowed them to leave in peace, having taken a selection of Viking hostages and received their vows never again to plunder within Alfred’s borders. Perhaps it was a disappointment for the Wessex army to have trained intensely for years and ridden hard for several days only to have the Danes flee the moment the Wessex army approached. But clearly there was good reason to consider the episode a victory for the Anglo-Saxons. Rochester was liberated. The slaves and horses held by the Danes had been abandoned to the Saxons. The Vikings had fled without receiving one piece of danegeld.

There was also good reason to be unsatisfied with the outcome of this encounter. Predictably, the terms of peace the Vikings had used to purchase their freedom were quickly broken as the army again plundered south of the Thames, within Alfred’s land. Even more disconcerting, this raiding band seemed to be working in conjunction with another Danish force based in East Anglia. Though King Æthelstan had proved faithful to his vows and never again raided in Wessex, not all of the noblemen under the converted Viking were as prepared to honor the terms of Æthelstan’s peace with Alfred. Wanting to send a picture of the power of Wessex to the East Anglian kingdom, Alfred ordered the English navy, loaded with the fighting men of Kent, to move north up the coastline of Kent seeking out opportunities to challenge the Viking fleets.

Upon reaching the mouth of the river Stour, the Wessex fleet immediately encountered a line of sixteen Danish longboats, fully rigged for battle. Immediately the Vikings advanced to meet the Saxons, and a vicious sea battle commenced. Assuming the Viking vessels were manned by an average of thirty men per ship, the Danish force likely had nearly five hundred men in the engagement. It is not known exactly how many fighting men the Wessex navy brought, but it is likely that the English force significantly outnumbered the Danes. Hours of fierce ship-to-ship combat followed, punctuated by occasional intense chases as one ship broke free of the flotilla and rowed madly for safety only to be overtaken, boarded, and forced back into the fight; finally the slaughter ended with every single Viking boat captured, her crews dispatched, and her plunder seized.

Exulting in the triumph and heavy-laden with their pillaged winnings, the Wessex navy finally regrouped and turned to move back down the Stour, anxious to return home and begin the celebrations. However, from the moment the naval combat had begun, word of the arrival of the Wessex fleet and her bold attack on the Danes had been passed to every Viking crew in the vicinity. By the time the Anglo-Saxons had hoisted their sails to begin a leisurely journey home, an enormous Danish fleet had gathered to meet the Saxon navy at the mouth of the Stour and exact their revenge. This time it was the Saxons who were outnumbered as the swelling tidal waters of the Stour teemed with Viking longboats, swarming the battle-weary Saxon fleet. The battle ended poorly for the Saxons that day as all was lost to the victorious Viking navy.

This series of engagements provided Alfred with several important lessons. First, the theory behind his massive reorganization of the Wessex defenses was perfectly sound. A network of well-fortified burhs, combined with a swiftly moving standing army had the potential to completely immunize Wessex from the tactics of the Danish raiding armies that had so plagued the Anglo-Saxons. But the second lesson proved more discouraging. The Danes still ruled the sea. Until Wessex could rob the Vikings of this strength, until Alfred could successfully defend his own shorelines, England would never truly be free from the plague of the Northmen.

The thought that the Danes still dominated the coasts of Britain weighed heavily on Alfred’s mind, and he often turned his mind to the problem of his navy, wondering how the Saxons could possibly find an advantage over the navies of the Danes. Alfred, however, was not interested in finding the solution to this problem purely out of a concern for the coasts of Britain. In truth, the king had always been transfixed by the sea and eagerly sought opportunities to sail. Had the obligations of the crown not demanded that he devote his life to the land of Wessex, Alfred would very likely have earned a reputation as an explorer on the sea, the “path of the daring.” Alfred’s writings regularly employed nautical images and metaphors that hint at the spell the sea had cast on Alfred’s mind. Thus, thinking through the renovation of his navy was in many ways an entertaining hobby more than a kingly duty.

It would not be until many years later that Alfred would finally have the opportunity to act upon some of the innovations he had concocted in his daydreams about the Saxon ships. Toward the end of his reign in the year 896, Alfred finally had the opportunity to give his full attention to the Wessex navy and ordered the construction of a fleet of Saxon ships according to a new set of specifications. With an eye toward combating the deadly longboats, having felt the power of these lethal ships skillfully constructed of ash wood, Alfred insisted that the new Saxon boats be almost doubled in size, with sixty oars per ship.

This new design placed more men at the oar, with the hopes of increasing speed in close chases, but more important it ensured that the English boats would arrive for combat with twice the number of soldiers ready for battle. Boarding one of Alfred’s longboats would be a much more formidable task. Contemporary accounts of Alfred’s new vessels state that the new ships sailed faster, handled better, and rode higher in the water than any other naval design (a tremendous advantage in ship-to-ship fighting). To train his new navy, Alfred recruited a number of experienced Frisian sailors from the continent, men well reputed for their seamanship.

Alfred’s foray into shipbuilding and his organization of a standing naval force won for him the title “the Father of England’s navy.” Predictably, this designation is hotly contested by military historians since it is impossible to trace an unbroken line of descent from Alfred’s organization of the Wessex naval forces all the way down to the United Kingdom’s present Royal Navy. That position is more likely held by Henry VIII. Thus, the concern to “demythologize” Alfred the Great compels some to object to this title being given to the king of Wessex. But it seems that King Alfred played enough of a prominent role in the origins of the English naval forces that he could reasonably claim some portion of this honorary title.

Alfred’s shipbuilding innovations have been the focus of a great deal of scholarly scorn because of a skirmish between Saxon and Danish forces that was fought shortly after the new fleet was constructed. In the year 896, Danish longboats struck again all along the southern coast of Wessex, plundering and pillaging the Saxon shore. In response to this threat, Alfred commanded his new ships to patrol the coastal waters, looking for an opportunity to punish the Viking pirates. Finally, word came to him that six Danish longboats were looting the coastal villages of the Isle of Wight and the shores of Devon. Alfred sent nine of the newly constructed Saxon ships, manned with mixed crews of Frisian and Wessex sailors, to engage the Northmen. The Wessex fleet, after much searching, overtook the Danish longboats as they rested at the mouth of one of the many rivers that emptied into the channel.

The Vikings were caught in a difficult position. The ships of Wessex had effectively cut off their opportunity to sail out the mouth of the river. If they attempted to row upstream, they would eventually be overtaken by the new large Saxon vessels and would only be that much more exhausted for the inevitable combat. And, to make matters much worse, the Saxon fleet had arrived just after half of the Viking force had beached their ships and disembarked to scout out the woods behind the beach.

Thus, as the Wessex ships cut off the escape to the channel and began closing in on the now panicking Vikings, half of the Viking ships sat beached on the shore and unmanned while the other three sat in the water trying to decide how to escape. As the tide ebbed and the waters of the bay slowly drained out, the three Danish vessels still afloat decided to make a run for it, rowing hard for the mouth of the bay, hoping desperately to find some gap in the Saxon blockade through which they could shoot to freedom.

But they could find no gap. All three of the fleeing Danish ships were easily overtaken before they had reached the mouth of the river. Then, in the shallow waters of the bay, the Saxon marines boarded the Viking vessels and turned their Danish hulls into floating fields of slaughter. They cut their way on board, and they waded through the muck and blood-filled bilge of the Viking boats. Significantly outmanned, the Danish sailors were ruthlessly slaughtered, having had little hope of escape. However, since this sea combat unfolded as the flotilla drifted in the ebbing tide, the flood soon drained out of the estuary leaving the longboats stuck fast in the sloppy muck of the muddy river banks. But not all of the ships were equally stranded in the mire. One of the Viking ships was able to break free from the grasp of the Saxon fleet and made for the open water of the channel. By the time they had shaken themselves free from the English sailors, there were only five surviving Vikings left in the ship.

The Saxon ships were all stuck fast in the mud, having been beached by the retreating tide of the estuary along with the five remaining Danish crafts. As the historical account records, they were “very awkwardly aground.” Three of the Saxon ships had been stuck fast on the same side of the river as the three Viking ships, which had been previously beached by the Danes who were scouting out the surrounding woods. The remainder of the Saxon fleet was grounded on the other side of the river, leaving the three Wessex ships separated from the rest of their navy. Meanwhile the Vikings who had been exploring the neighboring forest had now returned and, after evaluating the situation, decided their only chance of survival was to launch an attack on the crews of the three Saxon vessels beached on their side of the river.

Seeing the approaching Danes, the Saxons quickly clambered out of their beached craft and made ready for the coming melee. It was a sloppy affair, splashing into combat through the shallow tidal pools and fighting the pagan raiders in the muck and mire of the muddy river bank. Somewhere in the midst of this fight, the tide turned and the flow returned its waters to the bay. By the time the tide began to rush back up the river mouth, filling the estuary and washing clean the bloody gore of the afternoon’s combat, the Saxons had forced the Danish pirates to pay a heavy price. One hundred and twenty Vikings lay hewn down in the mud, compared to sixty-two Saxons cut down in the skirmish. As the river climbed back up the shoreline and began to lap at the grounded ships, the crews, seeing that their ships would soon be floating free in the rising waters, turned from the fight to return to their boats. The longboats of the Vikings were the first to be freed by the rising tide, giving them the opportunity to sail free from the bloodied estuary well ahead of the Saxon ships.

The battle on the riverbank had taken its toll on the Viking crews, who were now badly wounded, battle-weary, and numbering significantly fewer than when they had first begun their raiding. As they fled back to Viking-held Northumbria, they were hard-pressed to make progress against the contrary winds and tempestuous seas off the coast of Sussex. Lacking the strength to press on, two of the three fleeing ships were cast onto the shores of Sussex.

Unfortunately for the crews of these two vessels, word had already been sent to the fyrd of Sussex, alerting the shire to the approach of the limping Viking fleet. Thus, as the Vikings stepped ashore on the coast of Sussex looking for a moment’s respite, they were greeted by a large armed force, who immediately took them prisoner and marched them straight back to Winchester to be tried by King Alfred in his capital city. Alfred, at this point in his life, was in no mood to extend mercy to these brigands and ordered them hung as an example to any Dane who looked at the villages and monasteries of Wessex with piratical longing. Only one Viking crew returned to Northumbria, heavily wounded and probably ruing their earlier eagerness for a life of plunder.

Strangely, modern historians seem almost universally to interpret this naval encounter as a complete failure on Alfred’s part. The debate focuses on the evaluation of the king’s new designs for the construction of the Wessex ships, questioning whether the king’s innovations were effective. The scholarly bias is inexplicably against the king of Wessex on this issue, arguing that the encounter with the Viking fleet at the river mouth proved Alfred’s design was a disaster and a total failure. The point is made that the king’s demand for a larger hull, making room for sixty oars rather than for thirty, must have resulted in a significantly deeper draft. This deeper draft, they speculate, must have caused the Saxon vessels to more easily run aground during the naval battle in the shallow estuary, giving the Vikings, whose longboats must have had a shallower draft, the advantage in the fight.

It would be difficult to deny that Alfred’s design likely resulted in a deeper draft, though the historical account insists that they were more maneuverable than other ships. But it is impossible to insist that this was the primary reason the Wessex ships ran aground. Even if Alfred’s new design did result in a deeper draft, the manpower the new design afforded surely also added significantly to the speed with which the Wessex ships were able to cut off the Vikings at the river mouth, as well as to the numbers with which the Saxons were able to attack the Vikings in the ship-to-ship combat and in the following melee on the beach. Clearly, the entire encounter was a victory for the Saxons, to which the new ship designs contributed greatly, contrary to the miserly estimation of the scholarly world.

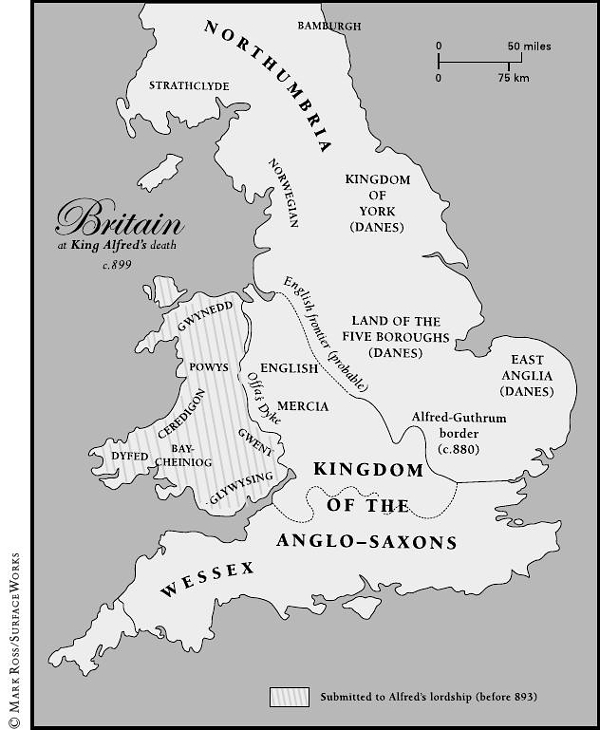

Part of the final settlement between Alfred and Æthelstan had been a treaty that formally established the border between the territories of the two kings. Since Ceolwulf, the Mercian puppet king installed by the Danes, had been moved along, Æthelstan now controlled Mercia as well as East Anglia. In the treaty drawn up between Alfred and Æthelstan, however, Mercia was to be divided between the Saxons and the Danes. Although negotiations continued regarding the specifics of this new boundary, the treaty eventually decreed that the border between the English territory and Viking land ran up the Thames, then up the Lea to its beginning. From there the border ran in a straight line to Bedford, at which point it met the Ouse, which it followed to Watling Street. All the land to the northeast of this line was designated as the Danelaw, the territory of the Danish kings. The land to the south and west of this negotiated border was left to Wessex and Mercia. This remaining portion of Anglo-Saxon Mercia was governed by an ealdorman named Æthelred, who had been chosen by the consensus of the rest of the Mercian ealdormen.

However, by the year 881, the northern Welsh kingdoms of Gwynedd and Powys had allied themselves with the Viking forces who held Northumbria and began to threaten both the southern Welsh kingdoms as well as the remaining portion of Mercia, now ruled by ealdorman Æthelred. After the Mercians suffered a major defeat at the battle of Conwy, they sought the assistance of Wessex, offering Alfred the position of king over Mercia, although Æthelred would still remain in place as the immediate Mercian ruler. Alfred agreed to this arrangement, taking Mercia and then the kingdoms of southern Wales into his protection. This new arrangement left Alfred as the only ruling Saxon left on English soil. Alfred was no longer merely the king of Wessex. He was now the king of the Anglo-Saxons.

Alfred’s new position as Mercian overlord could have offered the king many easy opportunities for taking advantage of the weakened kingdom, giving him chances to exploit the kingdom through taxes or make unreasonable demands for military service. However, Alfred had an enduring fondness for Mercia for a number of reasons. While still a young boy, Alfred had watched his older sister Æthelswith leave Wessex to marry the Mercian king Burgred, in an attempt to cement the friendship between these two kingdoms. The bond forged by this marriage held fast when the Mercian city of Nottingham was captured by the Danish raiding army in 867 and Alfred, still a young prince, had ridden with his older brother, King Æthelred, and the army of Wessex to deliver his sister’s nation from the Viking plague.

Though that particular siege ended with the Danes marching peacefully from the city with their pockets jingling with the danegeld, for Alfred the siege still seemed to end well, since he found, sometime during that siege, a Mercian bride of his own—Ealswith. Now Alfred offered to renew his commitment to this important ally. He sent his daughter, his firstborn child Æthelflæd, to be the wife of ealdorman Æthelred.

Ealswith had born Æthelflæd to Alfred at approximately the same time the prince had been fighting his first great battle, the battle of Ashdown. This young princess of Wessex grew up in the turbulent and eventful court of her father, throughout the most perilous years of the king’s reign. She had been old enough to remember vividly the night the family rushed from Chippenham under cover of darkness during Guthrum’s surprise winter attack. And she well remembered the darkest days of Wessex, hiding in Athelney with her parents, ever watchful of the Danish prowlers who hunted her and her family. She had also experienced firsthand the splendor of kingship as her father’s ultimate victory over Guthrum and his growing renown had brought fame and fortune to the once-destitute court of Wessex. Æthelflæd was thus a tremendous blessing to be granted to any ealdorman, since with her went the wisdom and experience of the Wessex court, as well as the love and affection of the great king.

Æthelflæd lived as the wife of the ealdorman of Mercia for twenty years, until Æthelred’s death around the year 908. Throughout his reign, Æthelflæd proved an invaluable aid to her husband as he sought to rebuild the infrastructure of Mercia, which had been ravaged by the concerted actions of pillaging Vikings and cowardly rulers over the course of decades. Since Mercia essentially formed the bulk of the Anglo-Saxon border with the Danelaw, the rebuilding of this nation was essential to ensure the future safety of the Saxons against the Danes.

Æthelred fell gravely ill with a debilitating illness several years before his death, and Æthelflæd ruled the kingdom in his place. Surprisingly, after her husband’s death, the Mercian nation continued to recognize her authority, making her one of the few Anglo-Saxon women to have wielded any sort of political power. Her people lovingly referred to the tough and battle-savvy woman as the Myrcna hlœfdige, or the “Lady of Mercia.” During her reign, Æthelflæd ordered the remodeling of a number of the Mercian towns into new Wessex-style burhs, following carefully the patterns and strategies she had learned at the feet of her father. This project expanded Alfred’s burghal defense system across all of Mercia. One generation later, Æthelflæd’s efforts to reorganize and strengthen Mercia against the Viking raiders became the critical foundation for a major Wessex campaign against the Danelaw, which finally dislodged the Vikings from the island of Britain entirely.

On several different occasions, Æthelflæd played the Old Testament Deborah and led the armies of Mercia in battle against the Danes to the north, driving the Viking armies from her northern borders.

Alfred’s first son, Edward, was born shortly after Æthelflæd and shared with his sister a clear childhood memory of their terrifying flight from Guthrum’s advancing forces. And though the two children shared many of the same dangers in their early years and learned together the same lessons that later shaped Æthelflæd into the great “Lady of the Mercians,” Edward, as the oldest son, was still set apart from Æthelflæd, being groomed from birth to take his father’s place as king of the Anglo-Saxons. What his sister picked up about kingship and war craft by careful observation from a safe distance, Edward learned in a sometimes dangerously close proximity—standing in Alfred’s court, witnessing charters, and personally leading the warriors of Wessex into battle against the Vikings, all before he had turned twenty years old.

In years to come, however, when Edward (later known as “Edward the Elder”) was to be crowned king of the Anglo-Saxons, he sent his son Æthelstan to be raised by Æthelflæd. King Æthelstan, having been raised under the tutelage of Alfred’s firstborn daughter, would be the king who would ultimately drive the Vikings from his territories, finally uniting all of the Anglo-Saxons under one crown.

Alfred’s other children are mentioned less in the historical accounts, so it is difficult to say much about their lives. His second daughter, Æthelgifu, was troubled by an illness of some sort, which forced her to keep her face always mysteriously covered. Eventually, the young princess, troubled by her illness, decided to devote herself to the service of God and took monastic vows as a nun.

Her father had ordered two monasteries to be built—the first was in the marshy wastes of Athelney and was given to a community of monks; the second was constructed at the gates of his Shaftesbury burh, and was given to his daughter Æthelgifu to rule as the abbess. Alfred ensured that the financial support for this institution was well established by endowing the abbey with a number of surrounding estates.

Between the prestige of the royal abbess and the wealth of the abbey’s generous endowments, the Shaftesbury abbey’s renown spread quickly. Soon Æthelgifu was joined by a number of other women who chose to devote their virginity to God at Shaftesbury. Strangely, Alfred had a much more difficult time establishing the monastery at Athelney since the Anglo-Saxon men seemed far less eager to take monastic vows that would dedicate them to a life of celibacy, prayer, and meditation on the Scriptures. To man the Athelney monastery, Alfred eventually had to resort to recruiting men from abroad, drawing from Wales, Old Saxony, Flanders, and even some of the young Danes.

Alfred’s youngest daughter, Ælfthryth, was given as wife to Baldwin II, the Count of Flanders. Even before this marriage into the house of Wessex, Baldwin already had several close connections to Alfred’s family. First, his mother was Judith, the daughter of Charles the Bald, who had become the unfortunate young second wife of Alfred’s father, shortly before his death. As the widowed queen of Wessex, she had then been shamefully taken as wife by Alfred’s older brother Æthelbald in a desperate attempt to demonstrate his own right to the throne. His subsequent reign was brief and tragic. After Æthelbald’s death in 860, Judith, now having reigned twice as the queen of Wessex despite being only sixteen years old, sold all her English property and returned home to West Francia. Her dismayed father placed her in the care of a monastery until he could once more arrange a suitable marriage for her. However, Judith outraged her family when the monks who served as her guardians reported that she had eloped with a mysterious count named Baldwin. Initially enraged and set on having the marriage annulled, her father eventually accepted his new son-in-law and entrusted him with the task of ruling the Viking-ravaged coast of Flanders.

Sitting opposite the channel from Alfred’s Kent, the region of Flanders had been equally despoiled by the intensifying Viking raids throughout the 860s to the 880s. As Count Baldwin and his son after him sought to defend their shores from the Danish scourge, it was only natural that the Counts of Flanders work in close cooperation with the Wessex king, who was essentially fighting the same battle as the Flemish. As a result of this partnership, the two kingdoms began to exchange defensive strategies and military intelligence. This partnership eventually led to increased trade between the two regions as well as a deeper bond of friendship and cooperation between their clergies.

Finally, this alliance was sealed when Alfred’s daughter, Ælfthryth, was given as bride to Count Baldwin II. Of Countess Ælfthryth little is known, except that her husband granted her request that at his death, rather than be buried at Saint Bertin in Saint Omer where only the male line of his family was permitted to be buried, he would instead be buried at the Abbey of Saint Peter in Ghent, where Ælfthryth could eventually be buried next to him. Whatever romance lies behind the story of this shared tomb can only be filled in by imagination.

Alfred’s youngest son, Æthelweard, had a very different childhood from his older brother Edward’s. Born in the year 880, Æthelweard’s boyhood coincided with the peace and prosperity of Alfred’s golden age. And while Æthelflæd and Edward had lived their youths as permanent fixtures of Alfred’s court, learning how to rule, Æthelweard devoted his life from an early age to learning the liberal arts. If Alfred’s will can be taken as evidence of his fatherly affections, then Æthelweard was clearly a well-loved son, receiving dozens of royal estates throughout Wessex at his father’s death. At his death, the prince was buried at the New Minster in Winchester, suggesting an enduring favor in the royal court throughout his brother’s reign as well.