THE INTEGRITY OF A SOLDIER

Charles Bates,

As told to Stephanie J. Fetsko

Born in 1916 in the Lawrenceville section of Pittsburgh, Charles Bates was the son of a steel construction worker. He was one of thirteen children, of whom seven died in infancy or early childhood. “Today my parents would have been investigated by Allegheny County Child and Youth Services, but that didn’t happen back then,” Charlie says. When he was five, his Irish Catholic parents moved the family to the predominantly German working-class suburb of Millvale, just across the Allegheny River from Pittsburgh. Charlie quit high school to help his family after his sophomore year. He was glad that he learned how to type in high school, as it was a skill that served him well for a lifetime career in the military.

Charlie knew he wanted to be a soldier even at the young age of fourteen. He did not pick a particularly propitious time to quit school. “It was 1932, and we were at the bottom of the Depression,” he says. Two years later, he entered the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps. Charlie loved it. “The CCC was a lot like the army,” he recalls joyously. “You lived forty-four men to a barracks, two hundred to a camp. A potbellied stove was our only heat. We fell out for reveille early and raised the American flag.” Like every other young man in the CCC, Bates earned a dollar a day. “We had to send twenty-five dollars home every month,” he says. “We got to keep five dollars. I saved my money. I worked at a camp on Tussey Mountain in Centre County, Pennsylvania, making firebreaks by hand with a rake, clearing brush.” At times they were even shot at by careless hunters and they had to hit the ground. Charlie says that the year he served in the CCC was his transition from a boy to a man.

Upon his discharge from the CCC, Bates got a job at McCann’s in downtown Pittsburgh working as a warehouseman. He tried to enlist in the army in early 1941, but they refused him due to his bad teeth. Then, on December 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. The United States was at war, and everything changed.

On January 12, 1942, only a month and five days after Pearl Harbor, Charlie joined the U.S. Army Air Corps. He was twenty-five years old. The army accepted him on waivers due to his dental problems, which were later corrected by an army dentist. He entered the military as a buck private, just like nearly every other guy entering the service.

Charlie was sent to Kessler Army Air Corps Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, for six weeks of indoctrination and training. “It was strict, but far from the rigorous training you often hear about,” he says. On February 26, 1942, Charlie and his fellow inductees embarked on a troop ship, the USS Haan, with no knowledge of their destination. They left the port of New Orleans and sailed into the Gulf of Mexico, which Charlie says was “infested with enemy submarines.” They proceeded through the famed engineering marvel, the Panama Canal, that Charlie had read about as a child.

His assignment as an aviation gasoline supply technician was to maintain the transfer of high-octane gasoline from oceangoing tankers from the Balboa docks to a jungle tank storage area approximately ten miles from the docks. Planes, ships, barges and other military forms of transportation utilized this fuel. In Panama, he was under an American civilian engineer, Mr. Lewis, whom Charlie describes as the “meanest man in the world” but who, oddly, “liked me.” Lewis said, “I want a man with stripes,” and in a year, Charlie had three stripes as a sergeant. Mr. Lewis invited Charlie to his home in Panama City. There he demonstrated his short temper and meanness by knocking his plate of fried eggs to the floor, complaining to his wife that he didn’t like the edges fried crisp. Lewis was on the phone once when lightning struck the line. The lightning knocked him down. He was so hated that one of Charlie’s fellow GIs asked, “Shall we call the ambulance for the SOB?” They did, and Lewis recovered.

There were about seventeen civilian Panamanian workers and one soldier who assisted Charlie in moving the gasoline. As they emptied the gasoline tanks, they replaced the gasoline with water to prevent explosion under the hot tropical sun. They had no mishaps. Since Charlie worked in a land of foreigners, he quickly learned some working Spanish words. He at least learned enough words to keep the fuel from blowing up or catching fire with the phrases “no fumar aqui” (no smoking here) and “muy peligroso” (very dangerous). Once in 1943, Charlie and his Panamanian crew were unloading a British tanker in the canal when a U.S. Marine demanded an ID from a British sailor. The drunken sailor, returning to his ship, said, “Go f--- yourself!” The marine shot him once in the stomach. Bates yelled to his Panamanian crew, “Abajo!” and everybody hit the ground. Charlie was afraid the marine would spray the entire group with bullets.

Only four days after Pearl Harbor, Pittsburghers in large numbers stopped at these war bond booths on Oliver Avenue at Smithfield Street, unmindful of the snowfall. Carnegie Public Library.

Loneliness and despondency took a surprising toll. A number of young soldiers committed suicide, a fact that was not publicized for fear of further demoralization. One barracks had so many suicides that it was even referred to as the “suicide barracks.” Even in his own barracks, Charlie awoke one night to the sound of a fellow soldier struggling to hold a rifle butt between his feet while aiming the muzzle at his head. Realizing that the solider was distraught over a recently received “Dear John” letter and intent on suicide with Charlie’s weapon, Charlie shouted at him, “Not with my gun, you don’t!” The reprimand was enough to jolt the soldier to his senses and save his life.

Charlie and the other soldiers went into Panama City on leave to go dancing. His officers ordered them to be careful about disclosing information to the girls with whom they spent their time for fear of German spies who were willing to pay for information. Charlie wonders how well the men took heed of this warning, especially under the influence of alcohol. “The soldiers were not at all careful,” he says. “Venereal disease was so widespread that they had a doctor inspect us. It was always a surprise visit.” The doctor came about every two or three months, often in the middle of the night. The GIs crudely called it a “short-arm inspection.” Soldiers went to Coconut Grove, a prostitution district. The potential for violence was incredible. Once a soldier had been returned to the base for fighting in Panama City and was incarcerated in the guardhouse. Prisoners were permitted exercise under armed guard, but when “the prisoner was giving him a hard time, the guard shot him right in the head,” Charlie relates. He did not witness the incident, but word of it quickly traveled across the base. Charlie found this job in Panama interesting and exciting work but obtained great satisfaction and a sense of relief when his tour of duty was completed. Charlie served twenty-eight months there.

On July 4, 1944, Charlie returned to the United States. He was sent to the Aviation Battalion at Geiger Air Corps Base in Spokane, Washington, for a short tour of duty until his transfer request came through for Hamilton Army Air Corps Base near San Raphael, California. In 1945, his work involved being an airplane flight dispatcher at Hammer Army Air Corps Base in Fresno, California. In an interesting story, one of the staff sergeants had a hot date. He was the engineer on a flight to San Francisco and talked Charlie into taking over for him. He told Charlie, “There’s nothing to it. You just watch the altimeter and the cylinder head temperature and a few other dials.” The flight arrived without incident, but the colonel wrote in his report, “Next time send me an engineer who knows what he’s doing.”

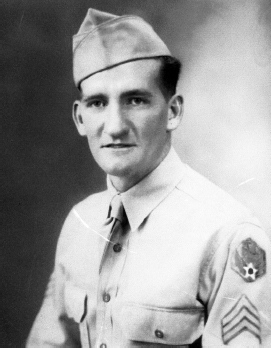

Sergeant Charles Bates, U.S. Army Air Corps. Charles Bates.

Since the war was coming to an end and many air bases were starting to close down, the army needed to supply logistical personnel to aid in handling the closures. The military assigned Bates, along with ten soldiers who had no prior experience in this capacity and were waiting to be discharged from the service, to close the bases. He was able to train them to accomplish the assignment with precision and accuracy. In addition, his role was to assist in closing the hospital’s eight surgical operating units.

After the war ended in August 1945, Charlie, still haunted by his memories of the Great Depression, decided to make the military his career. He volunteered for the U.S. occupation of Japan. His Japanese tour was from March 1947 to September 1948. During this time, Charlie was promoted to staff sergeant, serving as warehouse supervisor while with the 591st Air Material Squadron, Ashiya Air Base, Japan. He worked in logistics, keeping track of inventory and ordering parts. It was a very pleasant and interesting experience to learn the culture of the Far East. He had a very unusual meeting with some people who were in Japan when Hiroshima was bombed. He says that it was a pleasure to speak with a German priest and several groups of Catholic nuns from Ireland, England, France and Germany who aided the elderly people left to die in the streets of Kokura, Japan. He recalls a happy memory of a time when his unit had some surplus nylon parachutes that were to be destroyed. When the nuns who worked at one of the orphanages became aware of this, they asked if they could use this material for making clothing. So he donated the parachutes. Later, Charlie learned that the nuns had made beautiful First Holy Communion dresses for the Japanese children.

The August 15, 1945 issue of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette announced the end of the war. Cartoonist Cy Hungerford held out the prospect for a world without war. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.

Once back in the United States, Bates took advantage of every educational opportunity to which he was entitled that he believed would advance his military career. His military courses included personnel management; redistribution and marketing; equipment cooling specialist; refrigeration and air conditioning specialist; and automotive and diesel repairman. After serving assignments as close to home as the Pittsburgh airport in Coraopolis and as remote as Grand Forks, North Dakota, Master Sergeant Charles Bates retired from the 464 3rd Support Squadron, Semi-Automatic Ground Environment, on May 30, 1962. He was ready to head back home to Pittsburgh. Charlie became a civilian and received his retirement orders from the armed forces after service of twenty years, four months and eleven days.

When Charlie served as a disposal agent at the Greater Pittsburgh Airport Air Reserve Center in Pittsburgh in 1985, a Pittsburgh newspaper interviewed him regarding a mysterious phone call he received while working at the center. This call concerned the B-25 bomber that had crashed into the Monongahela River. This plane had been an inventoried item that was sold. The mysterious caller inquired whether he could purchase parts of a similar plane, making it appear as though the plane had been found. Bates informed the caller that he would have to contact the plane’s owner. When the caller was asked for his name, he ended the call. The mystery of the B-25 bomber, known as the Ghost Bomber of the Monongahela, began on January 31, 1956, and continues to this day.

In civilian life, Charlie remains active in the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). He helped his community preserve a World War II monument in a park near his home. A very interesting person who has a very positive attitude about his life and career as a soldier, Bates loved the military and has no regrets about participating in a part of history that will never be forgotten. He is proud to have served his country and would do it again. He feels that the United States’ involvement in World War II was a necessity that helped regain peace and balance in the world. His other great love was his wife, Mary, to whom he was married in 1948. They were married for fifty-six years. Charlie described her as a very compassionate and loving person, and it was not until after her death that he found that she had kept every letter he had written to her while he was overseas in the service. Charlie thought the world of Mary and deeply appreciated her loving devotion and her support of his military career.