10

children on the homestead

This book is probably not the place for an extended discussion of our parenting and educational philosophies, but in the interest of full disclosure, I should probably mention that our sons are educated at home via a life-learning process most popularly known as “unschooling.” I don’t think children have to be unschooled or homeschooled to be incorporated into a homestead, but it sure doesn’t hurt, if only because it means they’re around a heck of a lot more than they’d be if they were in school. A while back, Penny and I calculated how many hours our sons would have passed in school if we’d made that choice many years ago. For Fin, who is at an age that would correspond with seventh grade, it was 9,000 hours, not counting commuting time and homework.

Driving Melvin’s cows down for milking

In any event, incorporating our children into the day-in, day-out work and play of our homestead is a defining motivation. As adults, Penny and I know how good it feels to be capable and to feel as if we are contributing to something that is both productive and tangible. This is not something children are often able to experience in modern first-world cultures, since the vast majority of the hands-on labor necessary to provide the essentials of our survival has been subcontracted, either to technology or to underpaid (and all too often flat-out exploited) workers.

Clearly children benefit from precisely the same sense of satisfaction that comes of feeling needed. Of feeling and actually being useful. Of knowing that their efforts matter, that they are part of something that is larger than themselves but is also not abstract, as so much of contemporary childhood experience has come to be, rooted as it is in digitized interactions and make-believe worlds.

Sometimes I think about how much my sons love to drive our neighbor’s cows down to his barn for evening milking. Melvin pastures his small herd of Holstein, Jersey, and Brown Swiss in a field that abuts our southern boundary, and in the late afternoons, the boys scamper across the property line and circle around the cows, pushing them toward the barnyard that’s nearly half a mile away.

Penny and I used to think Fin and Rye coveted this task primarily because it’s fun, but we’ve come to understand that the attraction runs deeper: They love to drive Melvin’s cows because it is a tangible expression of their usefulness in the living, breathing, mooing world they inhabit. How can moving fifty 1,200-pound animals not bolster our sons’ confidence and, with it, their sense of capability? Fin and Rye are not paid to drive Melvin’s cows, and they receive no particular praise. Melvin thanks them, but never profusely. Driving the cows is something they are called to do for no other reason than it provides them a small measure by which to understand their role on this homestead, in this community, and even as people.

Before I go much farther, it seems important to address the role of patience when it comes to incorporating children into the homestead. Learning the patience to allow Fin and Rye to “help,” particularly in the early years, was no small task for Penny and me. It was during this period that Penny learned to make maps of each garden, rather than relying on the stakes she’d previously used to mark specific varieties, because the stakes were just too tempting for little hands to rearrange. The boys were constantly creating general disorder in the gardens, yet we wanted them to be in there with us, and so we had to devise ways to make it workable, even as we stretched the frayed limits of our patience and desire for orderliness.

How many bent-over nails have I pulled and replaced? How many seedlings has Penny replanted, their predecessors having been pulled by the boys in their attempt to “weed” the garden? How many boards have I had to help the boys cut through with a handsaw, all the while knowing it would be so much easier and quicker to push them aside and pick up the circular saw? How many more hours has it taken us to perform the simplest of tasks, and how frequently have we been sorely tempted to push our sons aside? The answer to all these questions, of course, is an awful lot. More than I even care to admit.

But over the past few years, we’ve witnessed a transformation in our sons. I suppose you might call it a return on our investment of patience and also our ability to let go of our expectations for how long a particular task might take or what it might look like when it was finished. Or you might just call it the inevitable maturing of their skills and judgment. Whatever you call it, Fin and Rye have evolved into truly productive contributors to our family’s health and wellbeing. When we slaughter pigs, they are right alongside us, capable of wielding both gun and knife. When we split wood, they split with us, and the piles around their splitting block grow almost as quickly as do Penny’s or mine. Our sons know which wild mushrooms are delicious and safe to eat and which can kill in minutes, and they can drive 12-penny nails with three precise swings of their hammers.

Just as Penny and I did not learn these skills because we hope to gird ourselves against the collapse of modern society and the inevitable chaos that will result, we did not facilitate our sons’ learning of these skills because we believe their survival is dependent on them. Rather, we believe that the resourcefulness and confidence their hands-on capabilities engender—along with the inevitable failures along the path toward attaining these skills—will provide the foundation necessary to support them no matter what career or lifestyle they choose.

I don’t mean to suggest that Fin and Rye are worker bees, always eager to tackle whatever project needs doing. Like most kids, they have their own agendas, and those agendas often clash with their parents’ wishes. But in those moments when we truly do need them, they almost always rise to the challenge. I believe that’s at least in part due to the fact that they know how useful they are.

youth at risk

There’s no question that incorporating Fin and Rye into our homestead has necessitated exposing them to a degree of physical risk that’s absent from most children’s lives in 21st-century first-world countries, although it’s worth noting that according to the National Highway and Traffic Safety Association, the leading cause of death for children 2 to 14 years old is car accidents.

Still, as a culture, we’ve become socialized to the risks inherent to vehicle travel, as well as the risks associated with consuming nutritionally bereft food, and physical inactivity, which according to the British medical journal The Lancet kills as many people annually as does smoking. Culturally speaking, we’re much less accepting of the risks—both perceived and real—that accompany many of the tools and tasks my sons engage with on a day-to-day basis.

This is a huge subject, but in short, Penny and I believe the invisible psychic and emotional risk of not exposing our children to these tools and tasks is far greater and ultimately more damaging than the risk of bodily injury. Furthermore, because the latter risk is the one that seems most visceral—after all, wounds to the psyche don’t bleed—we grant it more power than it deserves. It is difficult to see a child’s eroding sense of confidence and to articulate all the risks of that erosion; it is not difficult to see the wound left by the knife’s blade or from falling out of a tree.

Penny and I have noticed that the more we trust our children, the more trustworthy they become. The more responsibility we allow them, the more responsible they become. This seems like such an obvious equation, yet it’s one that has nearly been lost from our fearful and litigious society, which seems to believe that children are not to be trusted, nor granted responsibility, for fear they might be injured.

It is certainly not my place to advise parents on how much physical risk they should expose their child to. Obviously, any potentially dangerous tools and activities should be approached with commonsense caution, instruction, and supervision—and even still, physical risk cannot be eliminated. But in our opinion, the greater danger is not exposing our children to these risks in the first place. Penny and I consider it our responsibility to provide them with opportunities to become confident and proficient with the tasks and tools central to our work on this land.

incorporating kids into the working homestead

Over the dozen years we’ve been parents, we’ve developed a handful of tricks for incorporating the boys into our homestead. Two of those, patience and letting go of specific outcomes and expectations, are discussed above, and for good reason: They’re the hardest. Or at least, they were the hardest for us. Beyond that, there are a number of pragmatic ways to easily incorporate children of all ages into the homestead.

Since before the boys could walk, we’ve done everything we can to encourage their participation in chores and projects. In the early days, this literally meant wearing them on our chests or backs as we went about our business; as they grew older, it meant slowing our pace to a toddler’s wobbly shuffle and holding their hands as we made our rounds. Our feeling was that if our activities were “imprinted” on them from an early age, they wouldn’t feel like chores so much as just the way things were.

As soon as Fin could sit up unassisted, we dumped a pile of sand at the corner of what was then our primary garden. We populated the pile with numerous handed-down Tonka trucks and tractors, along with small shovels and implements of sandbox mayhem. This way, Penny and I could seed, weed, amend, and tend while the boys played, pushed, built, and bickered. As they got older and it became safe to do so, we situated a small wading pool by the garden’s edge so the boys could splash to their hearts’ content while we sweated and toiled in the rows. From time to time, one or both of the boys would toddle over to cover some seeds or—their favorite—squish a potato beetle.

About this time, Penny devoted a corner of one of our plastic hoop houses to “work” space for the boys, and they spent countless late-winter and early-spring hours in the greenhouse playing in the soil, while only inches away on the cold side of the plastic, the snow still lay 2 feet deep. When she seeded flats on the porch, she provided Fin and Rye with a soil-filled flat of their own, through which they contentedly pushed their small tractors and dozers back and forth, back and forth.

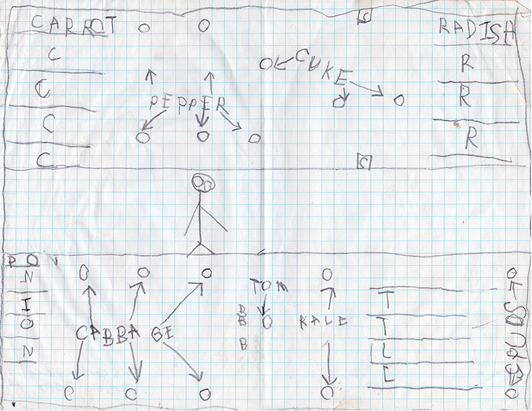

This lasted until the boys were about four, at which point, having been socialized to the garden almost since birth, each claimed a bed for his own. They painted crude signs to mark their territory and planted their favorite crops. Peas. Carrots. Potatoes. Garlic. Sweet corn. Keeping it a positive experience for all required us to pitch in; we allowed them to do the parts they wanted, and we picked up the slack when it came to the tasks they avoided, such as weeding.

Whatever efforts we invested have been repaid in full. The boys are now capable gardeners, though of course they’re still more interested in the harvest than anything else. And eating: They’re very interested in eating the vegetables they grow. From what we’ve heard from other parents, this phenomenon is not unique to our children.

As they demonstrated sound judgment and the necessary physical strength, their responsibilities expanded. After several busted “kid” tools, we learned it was well worth equipping them with high-quality implements, and that the initial higher cost was mitigated by durability. Emergency shovels designed for cars or camping are perfect for young hands, as are small camping axes and hatchets, which enabled them to fell small trees and de-limb branches right alongside us.

capable kids: tools for young hands

When they reached the age of four, respectively, Fin and Rye started asking for knives. This seemed young to us, but they’d watched us use our belt and pocketknives multiple times each day since they were born, and they understood that if they were going to be part of the “team,” they’d need their own cutting implement. Not without reservations, we presented them with locking-blade pocketknives, which they were initially allowed to use only in designated areas, under our supervision, until they’d gained the skill necessary to wield them unsupervised. Did they cut themselves? Of course they did, though never seriously. But even a deep cut is worth the confidence, skill, and feeling of being trusted those knives helped engender. When they did cut themselves, rather than exclaim over the blood and pain, we calmly reminded them where the bandages were. “Go ahead and clean it out and put a bandage on it.” Now we rarely know if one of them is injured until we see the bandage at day’s end.

These days, there are few tools Fin and Rye aren’t capable of using or have not been allowed to use. The chain saw is one; they’re simply not yet strong enough to counter the reactive forces of a saw. The table saw is another, but that’s probably not too far off, although table saws are probably responsible for more severed fingers than any other common power tool and must be approached with utmost caution.

The boys own and shoot guns; they now possess numerous knives, hatchets, and axes; are very capable with jigsaws and chop saws; and can drive both truck and tractor. They have not gained access to these implements at a prescribed age, but rather as they have demonstrated both the physical and mental capabilities. We do not believe that responsibility has birthdays.

Not long ago, I watched while Rye cut down a red maple tree for his sugar wood stash. Already, he had a good pile going, stacked and under cover, drying for the season to come. Anyway, he dropped the tree with his ax, and as I watched him land swing after swing with remarkable accuracy, I couldn’t help but wonder what it must feel like for a barely nine-year-old to have such mastery over a tool. I know the satisfaction it gives me to wield these implements with something approaching grace. It is a powerful and empowering thing and not something that should be reserved for adults alone.

sharing the load: children and chores

Often, other parents ask us if Fin and Rye have mandatory chores around the homestead. The short answer to this question is no, but that’s also not quite the most accurate answer, so I’ll expand on it a bit.

Penny and I feel as if our primary objective is to instill in our sons a sense of appreciation and affection for the hard-but-honest work of running a farm or homestead. Along those lines, we have always tried to model how much we value and appreciate this work, even in those moments when appreciation is farthest from our minds. And those moments certainly happen. There are times when we can’t fake it, when we’re tired or in a bad mood or one of us slips in manure while carrying a dozen eggs and . . . you get the picture. But by and large, we manage to approach even the least pleasant task with good humor, in part, because we genuinely feel that good humor.

As the boys have grown older, we have sought ways for them to contribute in the context of self-directed chores. We’ve facilitated various chore-based enterprises for them, from raising turkeys and ducks for sale, to their current small herd of goats. The boys know they have to do the work necessary to properly care for these creatures, but because they feel ownership, it does not feel like a burden, and that sense of burden is precisely what we’re hoping to avoid. We know of many adults who grew up on farms and never want to set foot in a barn again, in large part, because they have painful memories of being forced to do chores while their friends gathered for a game of baseball or hide-and-seek.

Of course, Fin and Rye do contribute to the household needs beyond caring for their own animals, and this happens more and more as they mature. They have always loved and been involved in haying, for example, and they like splitting wood. They are extremely helpful during slaughter or whenever we need to move the sheep from one pasture to another. As they’ve grown older, we expect more help from them, but we still allow them to have some autonomy over what form that help takes. For instance, this winter Fin has chosen to keep the kitchen woodbox full, and on the few occasions when I’ve stepped in because he forgot or got distracted, he’s come running. “That’s my job,” he says. “Hand me that wood.” In short, they know they need to chip in to keep things running around here, but we let them choose what their chipping in consists of. This keeps things positive and more fun for everyone, though we’re still waiting for them to choose washing dishes.

One final word on working together as a family: Rather than determine we’re going to work on a project for a set amount of time, Penny and I prefer to set a specific goal of finishing that project or at least a predetermined portion of it. The idea is to set reasonable goals that can actually be met and also to instill the importance of sticking with a project until it’s finished, and not merely until the clock says it’s time to stop, because a homestead is not a 9 to 5 prospect. We also emphasize that by making it a team effort, we’ll be finished more quickly and have more time for other activities. “Let’s get this pile of firewood finished so we can sneak in a mushroom walk before dinner,” I’ll say. Or “Once all this hay is in the barn, I’ll race you to the pond.” The beauty of this approach is that not only does it motivate the boys, it motivates us.