1

Economics and Liberating Theory

Unlike mainstream economists, political economists have always tried to situate the study of economics within the broader project of understanding how society functions. However, dissatisfaction with the traditional political economy theory of social change known as historical materialism has increased to the point where many modern political economists and social activists no longer espouse it, and most who still call themselves historical materialists have modified their theory considerably to accommodate insights about the importance of gender relations, race relations, and the “human factor” in understanding social stability and social change. The liberating theory presented in this chapter attempts to transcend historical materialism without throwing out the baby with the bath water. It incorporates insights from feminism, anti-colonial and antiracist movements, and anarchism, as well as from mainstream psychology, sociology, and evolutionary biology where useful. Liberating theory attempts to understand the relationship between economic, political, kinship and cultural activities, and the forces behind social stability and social change, in a way that neither over nor underestimates the importance of economic dynamics, and neither over nor underestimates the importance of human agency compared to social forces. Whether the theory of people and society that follows accomplishes all this while avoiding unwarranted assumptions and unnecessary idiosyncrasies is for you, the reader, to judge.1

People usually define and fulfill their needs and desires in cooperation with others – which makes us a social species. Because each of us assesses our options and chooses from among them on the basis of our evaluation of their consequences we are also a self-conscious species. Finally, in seeking to meet the needs we identify today, we choose to act in ways that sometimes change our human characteristics, and thereby change our needs and preferences tomorrow. In this sense people are self-creative.

Throughout history people have created social institutions to help meet their most urgent needs and desires. To satisfy our economic needs we have tried a variety of arrangements – feudalism, capitalism, and centrally planned “socialism” to name a few – that assign duties and rewards among economic participants in different ways. But we have also created different kinds of kinship relations through which people seek to satisfy sexual needs and accomplish child rearing and educational goals, as well as different religious, community, and political organizations and institutions for meeting cultural needs and achieving political goals. Of course the particular social arrangements in different spheres of social life, and the relations among them, vary from society to society. But what is common to all human societies is the elaboration of social relationships for the joint identification and pursuit of individual need fulfillment.

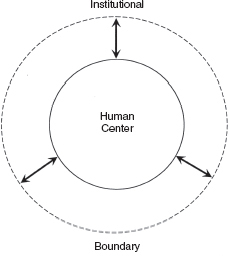

To develop a theory that expresses this view of humans – as a self-conscious, self-creative, social species – and this view of society – as a web of interconnected spheres of social life – we first concentrate on concepts helpful for thinking about people, or the human center, and next on concepts that help us understand social institutions, or the institutional boundary within which individuals function. After which we move on to explore the relationship between the human center and institutional boundary, and the possible relations between four spheres of social life.

Natural, Species, and Derived Needs and Potentials

All people, simply by virtue of being modern humans, have certain needs, capacities, and powers. Some of these, like the needs for food and sex, or the capacities to eat and copulate, we share with other living creatures. These are our natural needs and potentials. Others, however, such as the needs for knowledge, creative activity, and love, and the powers to conceptualize, plan ahead, evaluate alternatives, and experience complex emotions, are more distinctly human. These are our species needs and potentials. Finally, most of our needs and powers, like the desire for a particular singer’s recordings, or the need to share feelings with a particular loved one, or the ability to play a guitar or repair a roof, we develop over the course of our lives. These are our derived needs and potentials.

In short, every person has natural attributes similar to those of other animals, and species characteristics shared only with other modern humans – both of which can be thought of as genetically “wired-in.” Based on these genetic potentials people develop more specific derived needs and capacities as a result of their particular life experiences. While our natural and species needs and powers are the results of past human evolution and are not subject to modification by individual or social activity, our derived needs and powers are subject to modification by individual activity and are very dependent on social environment – as explained below. Since a few species needs and powers are especially critical to understanding how humans and human societies work, I discuss them before explaining how derived needs and powers develop.

Human beings have intellectual tools that permit them to understand and situate themselves in their surroundings. This is not to say that everyone accurately understands the world and her position in it. No doubt, most of us deceive ourselves greatly much of the time! But an incessant striving to develop some interpretation of our relationship with our surroundings is a characteristic of normally functioning human beings. We commonly call the need and ability to do this consciousness, a trait that makes human systems much more complicated than non-human systems. It is consciousness that allows humans to be self-creative – to select our activities in light of their preconceived effects on our surroundings and ourselves. One effect our activities have is to fulfill our present needs and desires, more or less fully, which we can call fulfillment effects. But another consequence of our activities is to reinforce or transform our derived characteristics, and thereby the needs and capacities that depend on them. Our ability to analyze, evaluate, and take what we can call the human development effects of our choices into account is why humans are the “subjects” as well as the “objects” of our histories.

The human capacity to act purposefully implies the need to exercise that capacity. Not only can we analyze and evaluate the effects of our actions, we need to exercise choice over alternatives, and we therefore need to be in positions to do so. While some call this the “need for freedom,” it bears pointing out that the human “need for freedom” goes beyond that of many animal species. There are animals that cannot be domesticated or will not reproduce in captivity, thereby exhibiting an innate “need for freedom.” But the human need to employ our powers of consciousness requires freedom beyond the “physical freedom” some animal species require as well. People require freedom to choose and direct their own activities in accord with their understanding and evaluation of the effects of that activity. In Chapter 2 I will define the concept “self-management” to express this peculiarly human species need in a way that subsumes the better known concept “individual freedom” as a special case.

Human beings are a social species in a number of important ways. First, the vast majority of our needs and potentials can only be satisfied and developed in conjunction with others. Needs for sexual and emotional gratification can only be pursued in relations with others. Intellectual and communicative potentials can only be developed in relations with others. Needs for camaraderie, community, and social esteem can only be satisfied in relation with others.

Second, needs and potentials that might, conceivably, be pursued independently, seldom are. For example, people could try to satisfy their economic needs self-sufficiently, but we seldom have done so since establishing social relationships that define and mediate divisions of duties and rewards has always proved so much more efficient. And the same holds true for spiritual, cultural, and most other needs. Even when desires might be pursued individually, people have generally found it more fruitful to pursue them jointly.

Third, human consciousness contributes a special character to our sociability. There are other animal species which are social in the sense that many of their needs can only be satisfied with others. But humans have the ability to understand and plan their activity, and since we recognize this ability in others we logically hold them accountable for their choices, and expect them to do likewise. Peter Marin expressed this aspect of the human condition eloquently in an essay titled “The Human Harvest” published in Mother Jones (December, 1976: 38).

Kant called the realm of connection the kingdom of ends. Erich Gutkind’s name for it was the absolute collective. My own term for the same thing is the human harvest – by which I mean the webs of connection in which all human goods are clearly the results of a collective labor that morally binds us irrevocably to distant others. Even the words we use, the gestures we make, and the ideas we have, come to us already worn smooth by the labor of others, and they confer upon us an immense debt we do not fully acknowledge.

Bertell Ollman explains it is the individualistic, not the social interpretation of human beings that is unrealistic when examined closely (Alienation, Cambridge University Press, 1973: 108):

The individual cannot escape his dependence on society even when he acts on his own. A scientist who spends his lifetime in a laboratory may delude himself that he is a modern version of Robinson Crusoe, but the material of his activity and the apparatus and skills with which he operates are social products. They are inerasable signs of the cooperation which binds men together. The very language in which a scientist thinks has been learned in a particular society. Social context also determines the career and other life goals that an individual adopts. No one becomes a scientist or even wants to become one in a society which does not have any. In short, man’s consciousness of himself and of his relations with others and with nature is that of a social being, since the manner in which he conceives of anything is a function of his society.

In sum, there never was a Hobbesian “state of nature” where individuals roamed the wilds in a “natural” state of war with one another. Human beings have always lived in social units such as clans and tribes. The roots of our sociality – our “realm of connection” or “human harvest” – are both physical-emotional and mental-conceptual. The unique aspect of human sociality is that the “webs of connection” that inevitably connect all human beings are woven not just by a “resonance of the flesh” but by a shared consciousness and mutual accountability as well. Individual humans do not exist in isolation from their species community. It is not possible to fulfill our needs and employ our powers independently of others. And we have never lived except in active interrelation with one another. But the fact that human beings are inherently social does not mean that all institutions meet our social needs and develop our social capacities equally well. For example, in later chapters I will criticize markets for failing to adequately account for, express, and facilitate human sociality.

People are more than their constantly developing needs and powers. At any moment we have particular personality traits, skills, ideas, and attitudes. These human characteristics play a crucial mediating role. On the one hand they largely determine the activities we will select by defining the goals of these activities – our present needs, desires, or preferences. On the other hand, the characteristics themselves are merely the cumulative imprint of our past activities on our innate potentials. What is important regarding human characteristics is to neither underestimate nor overestimate their permanence. Although I have emphasized that people derive needs, powers, and characteristics over their life time as the result of their activities, we are never completely free to do so at any point in time. Not only are people limited by the particular menu of role offerings of the social institutions that surround them, they are constrained at any moment by the personalities, skills, knowledge, and values they have accumulated as of that moment themselves. But even though character structures may persist over long periods of time, they are not totally invariant. Any change in the nature of our activities that persists long enough can lead to changes in our personalities, skills, ideas, and values, as well as changes in our derived needs and desires that depend on them.

A full theory of human development would have to explain how personalities, skills, ideas, and values form, why they usually persist but occasionally change, and what relationship exists between these semi-permanent structures and people’s needs and capacities. No such psychological theory now exists, nor is visible on the horizon. But fortunately, a few “low level” insights are sufficient for our purposes.

The Relation of Consciousness to Activity

The fact that our knowledge and values influence our choice of activities is easy to understand. The manner in which our activities influence our consciousness and the importance of this relation is less apparent. A need that frequently arises from the fact that we see ourselves as choosing among alternatives is the need to interpret our choices in a positive light. If we saw our behavior as completely beyond our own control, there would be no need to justify it, even to ourselves. But to the extent that we see ourselves as choosing among options, it can be very uncomfortable if we are not able to “rationalize” our decisions. This is not to say that people always succeed in justifying their actions, even to themselves. Nor is all behavior equally easy to rationalize! Rather, the point is that striving to minimize what some psychologists call “cognitive dissonance” is a corollary of our power of consciousness. The tendency to minimize cognitive dissonance creates a subtle duality to the relationship between thought and action in which each influences the other, rather than a unidirectional causality. When we fulfill needs through particular activities we are induced to mold our thoughts to justify or rationalize both the logic and merit of those activities, thereby generating consciousness-personality structures that can have a permanence beyond that of the activities that formed them.

The Possibility of Detrimental Character Structures

An individual’s ability to mold her needs and powers at any moment is constrained by her previously developed personality, skills, and consciousness. But these characteristics were not always “givens” that must be worked with; they are the products of previously chosen activities in combination with “given” genetic potentials. So why would anyone choose to engage in activities that result in characteristics detrimental to future need fulfillment? One possibility is that someone else, who does not hold our interests foremost, made the decision for us. Another obvious possibility is that we failed to recognize important developmental effects of current activities chosen primarily to fulfill pressing immediate needs. But imposed choices and personal mistakes are not the most interesting possibilities. At any moment we have a host of active needs and powers. Depending on our physical and social environment it may not always be possible to fulfill and develop them all simultaneously. In many situations it is only possible to meet current needs at the expense of generating habits of thinking and behaving that prove detrimental to achieving greater fulfillment later. This can explain why someone might make choices that develop detrimental character traits even if they are aware of the long run consequences.

In sum, people are self-creative within the limits defined by human nature, but this must be interpreted carefully. At any moment each individual is constrained by her previously developed human characteristics. Moreover, as individuals we are powerless to change the social roles defined by society’s major institutions within which most of our activity must take place. So as individuals we are to some extent powerless to affect the kind of behavior that will mold our future character traits. Hence, these traits, and any desires that may depend on them, may remain beyond our reach, and our power of self-generation is effectively constrained by the social situations in which we find ourselves. But in the sense that these social situations are ultimately human creations, and to the extent that individuals have maneuverability within given social situations, the potential for self-creation is preserved. In other words, we humans are both the subjects and the objects of our history.

We therefore define the concept of the Human Center to incorporate these conclusions:

People “create” themselves, but only in closely defined settings which place important limitations on their options. Besides the limitations of our genetic potential and the natural environment, the most important settings that structure people’s self-creative efforts are social institutions which establish the patterns of expectation within which human activity must occur.

Social institutions are simply conglomerations of interrelated roles. If we consider a factory, the land it sits on is part of the natural environment. The buildings, assembly lines, raw materials, and products are part of the “built” environment. Ruth, Joe, and Sam, the people who work in or own the factory, are part of society’s human center. However, the factory as an institution consists of the roles and the relationships between those roles: assembly line worker, maintenance worker, foreman, supervisor, plant manager, union steward, minority stockholder, majority stockholder, etc. Similarly, the market as an institution consists of the roles of buyers and sellers. It is neither the place where buying and selling occurs, nor the actual people who buy and sell. It is not even the actual behavior of buying and selling. Actual behavior belongs in the sphere of human activity, or history itself, and is not the same as the social institution that produces that history in interaction with the human center. Rather, the market as an institution is the commonly held expectation that the social activity of exchanging goods and services will take place through the activity of consensual buying and selling.

We must be careful to define roles and institutions apart from whether or not the expectations that establish them will continue to be fulfilled, because to think of roles and institutions as fulfilled expectations lends them a permanence they may not deserve. Obviously a social institution only lasts if the commonly held expectation about behavior patterns is confirmed by repeated actual behavior patterns. But if institutions are defined as fulfilled expectations about behavior patterns it becomes difficult to understand how institutions might change. We want to be very careful not to prejudge the stability of particular institutions, so we define institutions as commonly held expectations and leave the question of whether or not these expectations will continue to be fulfilled – that is, whether or not any particular institution will persist or be transformed – an open question.

Why Must There Be Social Institutions?

If we were all mind readers, or if we had infinite time to consult with one another, human societies might not require mediating institutions. But if there is to be a “division of labor,” and if we are neither omniscient nor immortal, people must act on the basis of expectations about other people’s behavior. If I make a pair of shoes in order to sell them to pay a dentist to fill my daughter’s cavities, I am expecting others to play the role of shoe buyer, and dentists to render their services for a fee. I neither read the minds of the shoe buyers and dentist, nor take the time to arrange and confirm all these coordinated activities before proceeding to make the shoes. Instead I act on the basis of expectations about others’ behavior.

So institutions are the necessary consequence of human sociability combined with our lack of omniscience and our mortality – which has important implications for the tendency among some anarchists to conceive of the goal of liberation as the abolition of all institutions. Anarchists correctly note that individuals are not completely “free” as long as institutional constraints exist. Any institutional boundary makes some individual choices easier and others harder, and therefore infringes on individual freedom to some extent. But abolishing social institutions is impossible for the human species. The relevant question about institutions, therefore, should not be whether we want them to exist, but whether any particular institution poses unnecessarily oppressive limitations, or instead promotes human development and fulfillment to the maximum extent possible.

In conclusion, if one insists on asking where, exactly, the Institutional Boundary is to be found, the answer is that, as commonly held expectations about individual behavior patterns, social institutions are a very practical and limited kind of mental phenomenon. As a matter of fact they are a kind of mental phenomenon that other social animals share – baboons, elephants, wolves, and a number of bird species have received much study. But just because our definition of roles and institutions locates them in people’s minds, where we have also located consciousness, does not mean there is not an important distinction between the two. It is human consciousness that provides the potential for purposefully changing our institutions. As best we know, animals cannot change their institutions since they did not create them in the first place. Other animals receive their institutions as part of their genetic inheritance that comes already “wired in.” We humans inherit only the necessity of creating some social institutions due to our sociality and lack of omniscience. But the specific creations are, within the limits of our potentials, ours to design.2

| • | The Institutional Boundary is society’s particular set of social institutions that are each a conglomeration of interconnected roles, or commonly held expectations about appropriate behavior patterns. We define these roles independently of whether or not the expectations they represent will continue to be fulfilled, and apart from whatever incentives do or do not exist for individuals to choose to behave in their accord. The Institutional Boundary is necessary in any human society since we are neither immortal nor omniscient, and is distinct from both human consciousness and activity. It is human consciousness that makes possible purposeful transformations of the Institutional Boundary through human activity. |

Figure 1.1 Human Center and Institutional Boundary

A social theory useful for pursuing human liberation must highlight the relationship between social institutions and human characteristics. But it is also important to distinguish between different areas, or spheres of social life, and consider the possible relationships between them. In Liberating Theory seven progressive authors called our treatment of these issues “complementary holism.”

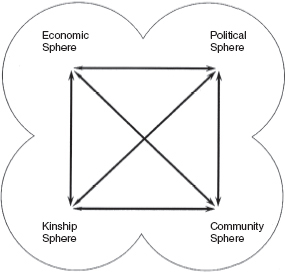

The economy is not the only “sphere” of social activity. In addition to creating economic institutions to organize our efforts to meet material needs and desires, people have organized community institutions for addressing our cultural and spiritual needs, intricate “sex-gender,” or “kinship” systems for satisfying our sexual needs and discharging our parental functions, and elaborate political systems for mediating social conflicts and enforcing social decisions. So in addition to the economic sphere of social life we have what we call a community sphere, a kinship sphere,3 and a political sphere as well. In this book we will be primarily concerned with evaluating the performance of the economic sphere, but the possible relationships between the economy and other spheres of social life are worthy of some consideration.

A monist paradigm presumes that one of the spheres of social life is always dominant in every society. For example, historical materialism considers the economic sphere to be dominant – even if only in the “last instance” – whereas feminist theories often treat the kinship or reproductive sphere as the most important, while anarchists trace all authority back to the political sphere. In contrast, complementary holism does not believe that any pattern of dominance among the four spheres of social life can be deduced from theoretical principles alone, and therefore known a priori to be true for all societies. Instead, complementary holism insists that any pattern of dominance (or non-dominance) is possible in theory, and therefore which sphere(s) are more or less dominant in any particular society can only be determined by an empirical study of that society.

All four spheres are socially necessary. Any society that failed to produce and distribute the material means of life would cease to exist. Many Marxists argue that this implies that the economic sphere, or what they call the economic “base” or “mode of production,” is necessarily dominant in any and all human societies. However, any society that failed to procreate and rear the next generation would also cease to exist. So the kinship or reproductive sphere of social life is just as socially necessary as the economic sphere. And any society that failed to mediate conflicts among its members would disintegrate. Which means the political sphere of social life is necessary as well. Finally, since all societies have existed in the context of other, historically distinct societies, and many contain more than one historically distinct community, all societies have had to establish some kind of relations with other social communities, and most have had to define relations among internal communities as well. This means that the community sphere of social life is as necessary as the political, kinship, and economic spheres.

Besides being necessary, each of the four spheres is usually governed by major social institutions which have significant impacts on people’s characteristics and behavior. This, more than their “social necessity,” is why complementary holism recognizes that all four spheres are important. But this does not imply any particular pattern of dominance. According to complementary holism there are a number of possible kinds of relations among spheres, and which possibility pertains in a particular society, at a particular time, must be determined by empirical investigation.

Figure 1.2 Four Spheres of Social Life

Relations between Center, Boundary, and Spheres

The human center and institutional boundary, together with the four spheres of social life, are useful conceptual building blocks for an emancipatory social theory. The concepts human center and institutional boundary include all four kinds of social activity, but distinguish between people and institutions. The spheres of social activity encompass both the human and institutional aspects of a kind of social activity, but distinguish between different primary functions of different activities. The possible relations between center and boundary, and between different spheres, is obviously critical.

It is evident that if a society is to be stable people must generally fit the roles they are going to fill. Actual behavior must generally conform to the expected patterns of behavior defined by society’s major social institutions. People must choose activities in accord with the roles available, and this requires that people’s personalities, skills, and consciousness be such that they do so. We must be capable and willing to do what is required of us. In other words, there must be conformity between society’s human center and institutional boundary for social stability.

Suppose this were not the case. For example, suppose South African whites had shed their racist consciousness overnight, but all the institutions of apartheid had remained intact. Unless the institutions of apartheid were also changed, rationalization of continued participation in institutions guided by racist norms would eventually regenerate racist consciousness among South African whites. Or, on a smaller scale, suppose one professor eliminates grades, makes papers optional, and no longer dictates course curriculum nor delivers monologues for lectures, but instead simply awaits student initiatives. If students arrive conditioned to respond to grading incentives alone, and wanting to be led or entertained by the instructor, then the elimination of authoritarianism in the institutional structures of a single classroom in the context of continued authoritarian expectations in the student body would result in very little learning indeed.

Social Stability and Social Change

Whether the result of any “discrepancy” between the human center and institutional boundary will lead to a re-molding of the center to conform with an unchanged boundary, or to changes in the boundary that make it more compatible with the human center cannot be known in advance. But in either case stabilizing forces within societies act to bring the center and boundary into conformity, and lack of conformity is a sign of social instability.

This is not to say that the human centers and institutional boundaries of all human societies are equally easy to stabilize. While we are always being socialized by the institutions we confront, this process can run into more or fewer obstacles depending on the extent to which particular institutional structures are compatible or incompatible with innate human potentials. In other words, just as there are always stabilizing forces at work in societies, there are often destabilizing forces as well resulting from institutional incompatibilities with fundamental human needs. For example, no matter how well oiled the socialization processes of a slave society, there remains a fundamental incompatibility between the social role of slave and the innate human potential and need for self-management. That incompatibility is a constant source of potential instability in societies that seek to confine people to slave status.

Similarly, it is possible for dynamics in one sphere to reinforce or destabilize dynamics in another sphere of social life. For example, it might be that the functioning of the nuclear family produces authoritarian personality structures that reinforce authoritarian dynamics in economic relations. Dynamics in economic hierarchies might also reinforce patriarchal hierarchies in families. In this case authoritarian dynamics in the economic and kinship spheres would be mutually reinforcing. Or, hierarchies in one sphere sometimes accommodate hierarchies in other spheres. For example, the assignment of people to economic roles might accommodate prevailing hierarchies in community and kinship spheres by placing minorities and women into inferior economic positions.

On the other hand, it is also possible for the activity in one sphere to disrupt the manner in which activity is organized in another sphere. For example, the educational system as one component of the kinship sphere might graduate more people seeking a particular kind of economic role than the economic sphere can provide under its current organization. This would produce destabilizing expectations and demands in the economic sphere, and/or the educational system in the kinship sphere. Some argued this was the case during the 1960s and 1970s in the US when college education was expanded greatly and produced “too many” with higher level thinking skills for the number of positions permitting the exercise of such potentials in the monopoly capitalist US economy – giving rise to a “student movement.” In any case, at the broadest level, there can be either stabilizing or destabilizing relations among spheres.

The stabilizing and destabilizing forces that exist between center and boundary and among different spheres of social life operate constantly whether people in the society are aware of them or not. But these ever present forces for stability and change are usually complemented by self-conscious efforts of particular social groups seeking to maintain or transform the status quo. Particular ways of organizing the economy may generate privileged and disadvantaged classes. Similarly, the organization of kinship or reproductive activity may distribute the burdens and benefits unequally between gender groups – for example granting men more of the benefits while assigning them fewer of the burdens of kinship activity than women. And particular community institutions may not serve the needs of all community groups equally well, for example denying racial or religious minorities rights or opportunities enjoyed by majority communities. Therefore, apart from underlying forces that stabilize or destabilize societies, groups who enjoy more of the benefits and shoulder fewer of the burdens of social cooperation in any sphere have an interest in acting to preserve the status quo. While groups who suffer more of the burdens and enjoy fewer of the benefits under existing arrangements in any sphere can become agents for social change. In this way groups that are either privileged or disadvantaged by the rules of engagement in any of the four spheres of social life can become agents of history. The key to understanding the importance of classes without neglecting or underestimating the importance of privileged and disadvantaged groups defined by community, kinship or political relations is to recognize that only some agents of history are economic groups, or classes. Racial, ethnic, religious, and national “community” groups; women, men, heterosexual, and homosexual “gender” groups; and enfranchised, disenfranchised, bureaucrats, and military “political” groups can also be self-conscious agents working to preserve or change the status quo, which consists not only of the reigning economic relations, but the dominant gender, community, and political relations as well.4

Digesting this dense presentation of something as complicated as a theory of society is a challenge for any reader. Unfortunately we can only afford limited space here to briefly discuss a few examples of how it can be applied.

South Africa between 1948 and 1994 is a useful case to consider. Of course during those years the economy generated privileged and exploited classes – capitalists and workers, landowners and tenants, etc. Patriarchal gender relations also disadvantaged women compared to men in South Africa, and undemocratic political institutions empowered a minority and disenfranchised the majority. But the most important social relations, from which the system derived its name, apartheid, were rules for classifying citizens into different communities – whites, colored, blacks – and laws defining different rights and obligations for people according to their community status. The relations of apartheid created oppressor and oppressed racial community groups who played the principal roles in the epic struggle to preserve or overthrow the status quo in South Africa. In other words, an open minded, reality-based analysis of what made this particular society “tick” would have rather easily come to the conclusion that the community sphere of social life was dominant, the struggle to preserve or overthrow apartheid relations between the white, colored, and majority black communities was central, racial dynamics affected class and gender dynamics more than the reverse, and during these years racial struggle was the “driving force” behind historical change. Because it holds that (1) any pattern of dominance is theoretically possible, and (2) empirical analysis is the only way to discover the pattern of dominance in a particular society, the complementary holist framework outlined in this chapter facilitates coming to this accurate evaluation.

This perspective need not deny that classes, or gender groups for that matter, also played significant roles in South Africa under apartheid. But a social theory that recognizes multiple spheres of social life, and understands that privileged and disadvantaged groups can emerge from any area where the burdens and benefits of social cooperation are not distributed equally, can help us avoid neglecting important agents of history. Unlike a monist theory like historical materialism which insists on prioritizing class, it can help us avoid misunderstanding what is actually going on in a situation like South Africa under apartheid. Complementary holism can also help us understand why not all forms of oppression will be redressed by a social revolution in only one sphere of social life – as important as that change may be. For example, while the overthrow of apartheid largely eliminated one form of oppression in South Africa, it has become apparent over the past two decades that it did little to change class oppression or exploitation.

But how might complementary holism be applied to help understand recent events? At the risk of underappreciating the severity of previous crises in the periphery of the global economy – such as the debt crisis and lost decade of the 1980s in Latin America and Africa, and the East Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s which Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman called “the greatest economic falling from grace since the Great Depression” – 2008 marked the beginning of economic turmoil unseen in the advanced economies since the 1930s. So if there was ever a time when economic dynamics and class struggle should have surged to the fore – or exhibited their “dominance” – this should be it.

Far from denying that economic dynamics and class struggle can be dominant, complementary holism holds that this is quite possible. Moreover, since according to complementary holism patterns of dominance can change, it is important for analysts using this social theory to be sensitive to any shifts. The response of the ruling class to an economic crisis of its making – bail out banks and creditors while subjecting the working majority to punishing austerity, no matter how counterproductive to economic recovery – demonstrates that far from being sated, ruling class appetite for class war has increased since 2008. We have also now seen popular uprisings in response such as Los Indignados in Spain, Un-Cut in the UK, and Occupy Wall Street in the US, screaming “no” to more economic deprivation. These are all signs that economic dynamics and class struggle are now more “front and center.” However, even during these years of extreme economic crisis and heightened class struggle it would be a mistake to underappreciate the importance of dynamics in other spheres of social life and non-class agents of history prominent in recent struggles around the world.

It would be a mistake to interpret movements like Occupy as merely challenges to class exploitation. While the 1% versus the 99% slogan nicely captures the economic component, unlike the mainstream US labor movement, Occupy also challenged the pretense that the US political system is any longer remotely democratic. Occupy has been just as critical of money taking over politics symbolized by the Citizens v. United Supreme Court decision, and of the corporate dominated, two-party duopoly as it has been of escalating economic inequality. After several weeks reporters from the Public Broadcasting System covering the occupation at Zuccotti Park asked demonstrators there: “OK, we know what you’re against – all the wealth going to the top 1% – but what are you for?” The demonstrators answered: “See our General Assembly? See us making decisions democratically? That is what we want. We want real democracy!” In other words, Occupy was a popular protest against a political system devoid of meaningful democracy as well as a protest against economic inequality.

Moreover, if we look around the world unencumbered by a monist theory which presumes economic dominance, it is apparent that more has changed in some non-economic spheres than in the economy since the onset of the economic crisis. And who is to say these changes are somehow of less significance? The truth is that at least as of the time of the writing of this second edition, there has been practically no change in the economic system, as neoliberalism remains on the throne everywhere it was prior to the crisis, despite its disastrous consequences. In the international economy the same kind of treaties are being negotiated. As a matter of fact, environmental provisions in the international economic treaties negotiated by the Bush administration between 2000 and 2008 had more teeth than environmental provisions do in the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement now being negotiated under even greater secrecy by the Obama administration. Domestically, center-left as well as right-wing governments in Europe and North America continue to preside over financial bailouts and fiscal austerity in one country after another, with only a difference in rhetoric. In short, despite all the economic turmoil, and change from “cold” to “hot” class war, there has been virtually no change in economic power or policy, and even less movement toward economic system change. At the same time, at least in the US we have seen a dramatic change in the kinship sphere of social life: The gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) movement, the only progressive movement which has been on the offensive instead of defensive recently, has achieved a major shift in popular consciousness regarding homosexuality and has made significant progress toward converting increasing popular tolerance toward sexual preference into greater political and institutional equality.

We have also witnessed dramatic changes in power and relations among major international “communities.” The Latin America “community” of nations has continued to make historic strides in freeing itself from domination by the “northern colossus.” Despite differences between the more “radical” bloc of Venezuela, Bolivia, Cuba, Ecuador, and Nicaragua, and the more moderate bloc of Uruguay, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Costa Rica, Latin America as a whole has greatly reduced US military power in the region, forged new international organizations of their own like ALBA and the Bank of the South while reducing US influence within the OAS, and reduced regional economic dependence on the US as well. By far the largest popular uprising in the past six years, the remarkable Arab Spring, was not primarily about economic issues in which protagonists were opposing classes.5 The Arab Spring was primarily a revolt against corrupt, authoritarian political regimes and their quisling peace with US–Israeli dominance over the region, i.e. it was primarily a revolt challenging the political status quo within several Arab countries, and disempowerment of the majority Arab “community” in the region as a whole. While, like Occupy, the Arab Spring has been quieted for the moment, combined with a partial US military retreat from the region, the Arab Spring has already shaken up relations among country, religious, and ethnic “communities” in the Mideast to an extent unseen since the end of World War II. Finally, the changes from a bipolar world between 1945 and 1989 where the US and Soviet Union “competed” as reigning superpowers, to a unipolar world between 1989 and 2010 with the US as lone superpower, to a world now adjusting to the rise of a new superpower, China, have all been transformations of historic importance in the community sphere of global society.

In any case, hopefully the conceptions of human beings, social institutions, and multiple spheres of social life comprising the skeleton of a “liberating” social theory summarized briefly in this chapter provide a proper setting for our study of “political economy” – one that neither overstates nor understates the role of economics in the social sciences. In Chapter 2 we proceed to think about how to evaluate the performance of any economy.

The original formulation can be found in Liberating Theory (South End Press, 1986) by Michael Albert, Leslie Cagan, Noam Chomsky, Robin Hahnel, Mel King, Lydia Sargent, and Holly Sklar. |

|

Thorstein Veblen, father of institutionalist economics, and Talcott Parsons, a giant of modern sociology, both underestimated the potential for applying the human tool of consciousness to the task of analyzing and evaluating the effects of institutions with a mind to changing them for the better. This led Veblen to overstate his case against what he termed “teleological” theories of history, i.e., ones that held onto the possibility of social progress. The same failure rendered Parsonian sociology powerless to explain the process of social change. |

|

Anthropologists often study what they refer to as “kinship systems.” However, feminists more often use the phrase “reproductive sphere.” In either case, this is the “sphere of social life” primarily concerned with the procreation and education of the next generation to become adult members of society. |

|

Broadly speaking the term “economism” means attributing greater importance to the economy than is warranted. It can take the form of assuming dynamics in the economic sphere are more important than dynamics in other spheres when this, in fact, is not the case in some particular society. It can also take the form of assuming that classes are more important agents of social change, and racial, gender, or political groups are less important “agents of history” than they actually are in a particular situation. |

|

Of course a majority who participated in the Arab Spring were from the working class, of course they were economically oppressed, and of course improvements in their economic conditions were called for. But this does not mean the Arab Spring was primarily a class movement, focused primarily on economic issues. Since ruling classes are small compared to working classes everywhere, the working class must necessarily comprise a large part of any movement that is popular, which does not mean that the movement is primarily about economic exploitation. A majority of African-Americans who participated in the civil rights movement of the 1960s were working class, and their deplorable economic conditions were among their grievances. But it would be inaccurate to conclude that the US civil rights movement of the 1960s was therefore primarily a class movement, focused primarily on economic exploitation. It was a movement in which an historically oppressed racial group, African-Americans, emerged as an agent of history and fought with some success against institutions and racist ideology that oppressed them specifically as a minority community. |