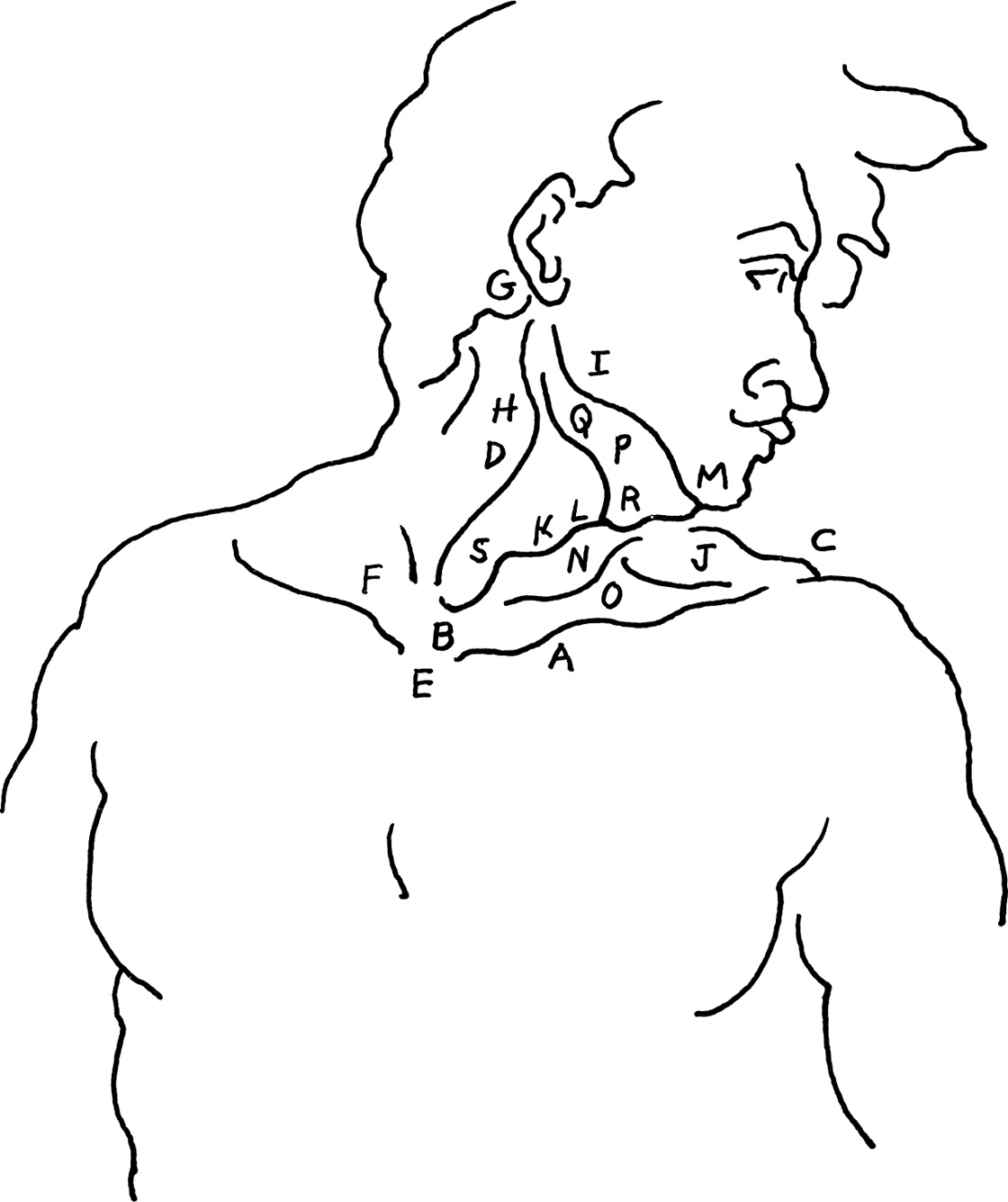

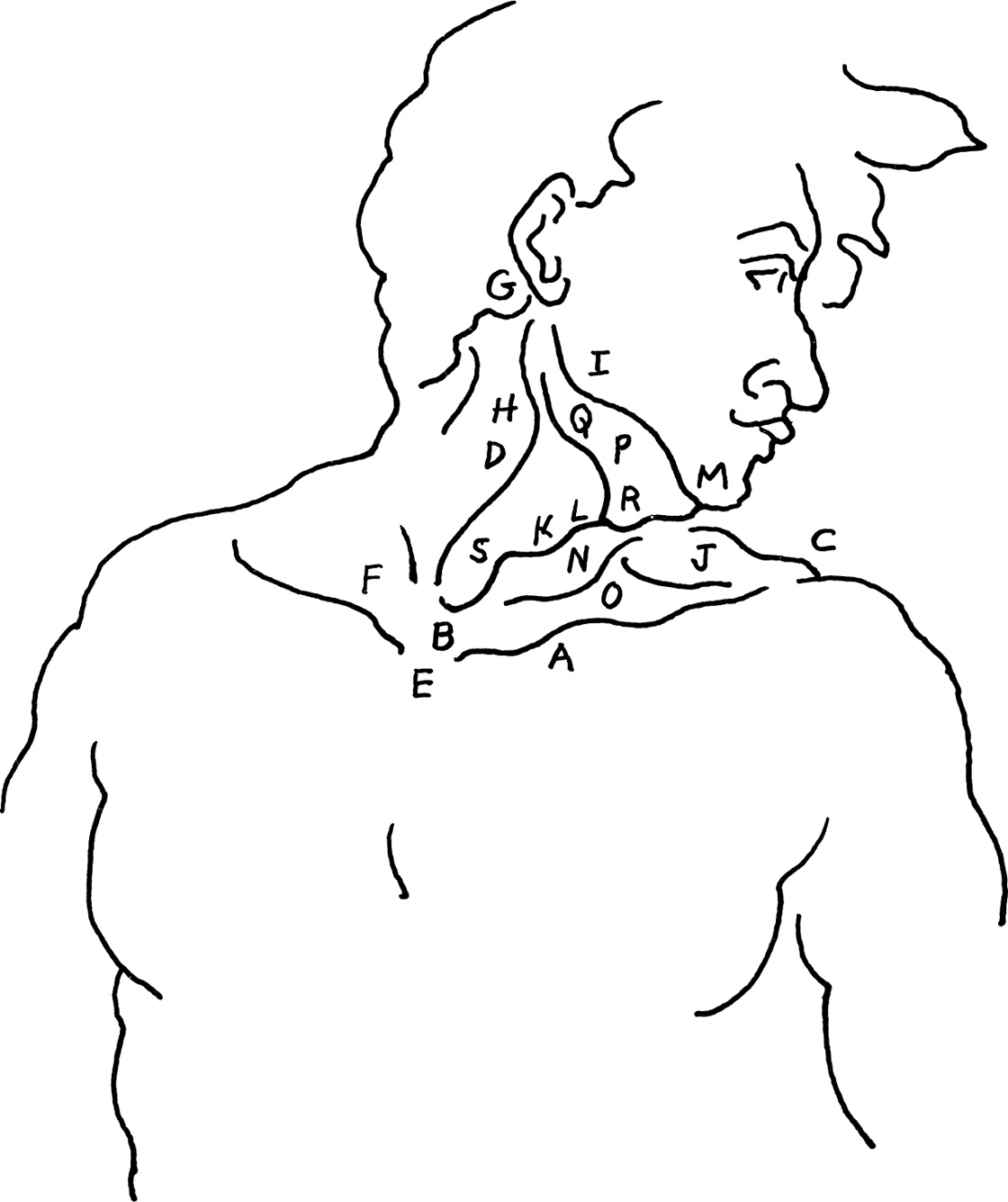

The inner base of the column of the neck arises out of the circle of the first ribs and follows the curve of the spinal column at the back. At the front, the lower limit of the neck is formed on each side by the clavicle (A), from the jugular notch (B) (or pit of the neck) to the acromion process (C) at the side.

In this drawing, the head, and the neck which always moves with it, are rotated to the viewer’s right. The sternocleidomastoideus (D), the most prominent muscle in the neck, spirals vertically downward, filling a large portion of this mass. This rotator, sometimes called the “bonnet string” muscle, extends from its cordlike origin in the manubrium (E) of the sternum and the inner third of the clavicle (F) to the mastoid process (G) behind the ear. The sternal head (H) swells just below the angle of the jaw (I) as it pulls the head back and rotates it toward the trapezius (J) at the side.

With the rotation of the head and neck, the prominent landmark of the thyroid cartilage or Adam’s apple of the larynx (K) is also pulled to the side. The middle line of the neck (L) that runs from the mental protuberance (M) (the center of the chin bone) to the pit of the neck (B) overlaps the relaxed sternocleidomastoideus (N) on the other side. This lowered sternocleidomastoideus is pushed obliquely toward the posterior triangle of the neck (O) and overlaps the anterior edge of the trapezius (J) at the shoulder.

A shaded down plane marks the submaxillary or digastric triangle and the area of the mylohyoid muscle (P). The posterior belly of the digastric muscle (Q) moves along the lower border of this triangle to the hyoid bone (R) at the front.

The thyroid cartilage (K), which is very prominent in the male neck, is accented by the strong contoured hatchings (S) that mark its down plane.

Domenico Beccafumi (1485/6-1551)

STUDY FOR PART OF THE MOSAIC FRIEZE OF THE SIENA CATHEDRAL PAVEMENT

pen and bistre wash

8″ × 11 5/8″ (203 × 295 mm)

Bequest of Meta and Paul J. Sachs

Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge

The contour of Michelangelo’s lines suggest the ball and egg shape of the head. The cylinder of the neck is formed on the spinal column, follows its curve, and takes on its supple character. At about the level of the middle of the ear, Michelangelo’s strong curve at the back of the head suggests the occipital protuberance (A), which is the upper limit of the neck. Below this eminence lies the bony ring of the atlas—the first cervical vertebra—on which the head moves forward and backward in flexion and extension, and beneath it, the axis on which the head is rotated. Together with the five vertebrae below, they form the back of the column of the neck.

Powerful ligaments and muscles, called the strong chords of the neck, connect the base of the skull and the vertebral column. They help to keep the head erect and assist in its movements. The trapezius or table muscle (B) moves down from its origin in the occipital protuberance. Molding itself on the deeper layers of muscle, the trapezius creates a longitudinal elevation (C) on each side of the nuchal furrow, the central furrow of the neck. This furrow follows down along the spines of the vertebrae to the important landmark of the seventh cervical or vertebra prominens (D). An imaginary line drawn from the seventh cervical to the acromion process (E) of the scapula defines the lower border of the posterior of the neck.

The outline of the upper section of the trapezius (F) is widened by the mass of the scalenus and the levator anguli scapulae beneath. The upper mass of the sternocleidomastoideus (G) outlines the neck above. Below, the outline changes direction as the fibers of the trapezius project obliquely upward from the acromion process (H) to about the fifth vertebra (I).

Michelangelo places the plane break along the upper edge of the trapezius (J) where a transverse fold (K) marks the sternocleidomastoideus (G) as it twists into the trapezius. In the light area, he subdues the contrast at the nuchal furrow, and in the dark mass of the face, he minimizes the reflected light to unify his two big values.

Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564)

FIGURE STUDY FOR THE BATTLE OF CASCINA

black chalk over stylus

7 5/8″ × 10 1/2″ (194 × 267 mm)

Albertina, Vienna

The sternocleidomastoideus (A), coursing down from its mastoid and occipital insertions behind the ear (B) to its origins in the sternum (C) and the inner clavicle (D), covers a wide area of the lateral region of the neck. Boucher has emphasized its middle portion (E) with contoured hatchings. At the pit of the neck (C), where the two sides of this “bonnet string” muscle (the sternocleidomastoideus) meet the front line of the neck, he has placed a dark accent.

A small, shaded area indicates the sternoclavicular fosset (F), where the clavicular portion of the sternocleidomastoideus inserts into the inner third of the clavicle. Above and behind this, a deeper depression (G), called the “salt box,” marks the area of the posterior triangle of the neck. This area is bounded in the front by the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoideus (H), in the back by the anterior edge of the trapezius (I) and below by the middle third of the clavicle (J). In the rotated and laterally inclined head, the posterior triangle is rounded out by the combined mass (K) of the three scaleni and the levator anguli scapulae that converge like the sternocleidomastoideus to the area behind the ear.

The column of the neck always curves slightly forward along with the curve of the vertebral column. This forward thrust is stronger in the female. Boucher has also softened the sharp prominence of the thyroid cartilage (L) in this female throat, but at the same time he has slightly filled out the area directly below (M) to allow for the larger thyroid gland in women.

Note how the base of the skull (N) at the back is well above the chin (O) and mental protuberance of the lower jaw. The long, graceful line of the trapezius (I) at the back of the neck, emphasizing the more flowing lines of the female, is broken up into three convex movements of varying lengths, rhythmically reflecting the influence of the underlying muscles.

François Boucher (1703-1770)

SEATED NUDE FACING RIGHT AND RECLINING ON CUSHIONS

chalk on gray paper

11 13/16″ × 15 7/16″ (300 × 392 mm)

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Movements of the head are usually combined. The head of Michelangelo’s model is extended upward, rotated, and slightly inclined to the right. At the back, the strong chords of the neck are assisted by the two sides of the trapezius acting together to cause extension of the neck and head.

The sternocleidomastoideus (A) contracts in the rotating of the head. This muscle is the dividing line between the two principal triangles of the neck, the almost hidden posterior triangle (B), and the anterior triangle (EDJ) at the front. The anterior triangle is defined above by the lower line of the jaw (C), in front by the imaginary center line of the neck (ED), and by the inner border of the sternocleidomastoideus (A).

The upper portion of the anterior triangle that lies under the chin (EGJ) is separated from the rest by the posterior portion of the digastric muscle (F) and the hyoid or tongue bone (G). This area is called the submaxillary or digastric triangle. A slight hollow in its center (E), marks the interval between the two bellies of the anterior digastric muscle lying over the broad mylohyoid muscle that fills this triangle.

Below the hyoid bone along the midline of the neck, a larger hollow (H) outlines the thyroid notch at the center of the thyroid cartilage or Adam’s apple.

At the side, the line of the omohyoid (I) moves down and outward from the hyoid bone, dividing the lower area of the anterior triangle into the superior (J) and inferior (K) carotid triangles. A transverse furrow separates the thyroid (H) and cricoid (L) cartilages. Below this, the masses of the thyroid gland and trachea or windpipe move down behind the pit of the neck (M). The clavicle (N) follows the upraised arm and approaches the column of the neck.

Michelangelo places his dominant plane break and strongest contrast along the edge of the most projecting part, the thyroid cartilage (H). Gradually softening this contrast, he moves his plane break downward along the throat, and upward along the anterior belly of the digastric muscle (E).

Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564)

STUDIES FOR THE CRUCIFIED HAMAN

red chalk

7 1/2″ × 10″ (191 × 254 mm)

Teyler Museum, Haarlem

Flexion of the neck and head is principally initiated by the three scaleni muscles in the lower neck and by the two sides of the sternocleidomastoideus (A), acting in unison. At the base of the skull (B), the condyles of the occipital roll upon the surface of the atlas or first cervical vertebra, and the head moves downward. When gravity begins to influence the downward movement of the weight of the skull, the antagonistic muscles, the strong chords of the back and the trapezius (C), take over to regulate the action of gravity upon the fall of the head.

The downward flowing hair counterbalances the upward thrust of the body lines, harmonizes with the flexion movement of the head, and by near parallelism, draws attention to the face.

In the highlight of the hair, Degas strikes two oblique lines (D), one curved to give the contour of the skull, and an adjacent straight line to turn the plane. Below this, the movement is continued with three straight lines (E) marking the important plane change of the occipital protuberance at the back of the skull.

At the back of the neck (F), short convex lines break up the larger movement, suggesting the strong chords beneath the mass of the trapezius and the prominence of the seventh cervical vertebra (G) and two or three dorsal vertebrae.

The flexion and rotation of the head causes the angle of the jaw (H) to push the sternocleidomastoideus (A) against the side of the trapezius (I), creating the deep flexion folds in the neck.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

AFTER THE BATH

charcoal on yellow tracing paper

13 7/8″ × 10″ (352 × 254 mm)

Clark Art Institute, Williamstown

The rotating head pulls upon the muscle and skin of the neck, causing the forms on that side to stand out firm and round (A). At the other side, the neck is crossed by oblique wrinkles between the sternocleidomastoideus (B) and the trapezius (C).

As the column of the neck curves forward, the seventh cervical vertebra (D) stands out in the midline of the back, and the forward and rotary motion is echoed in the folds of the gown.

Drapery covers like a second flesh. Its contours should harmonize with and give “clues” to the body forms over which it lies. Note how the fold at the back of the neck (E) curves, not just up to the line of the neck, but out and around the cylinder, helping to describe its form. This fold contours down over the shapes of the back in a sweeping curve that breaks up into smaller segments that converge with other curves from above and below to a common source at the vertebral column (F) in the back.

The observant artist knows that different kinds of cloth each have their individual “cluster characteristics,” just as do the different species of trees in the landscape. The particular construction of the cloth, its texture and density, determine the types of forms that it takes as it falls over the figure.

Finally, the artist concerns himself with the varied design arrangements of the lines, shapes, sizes, and directions of the material in his figure drawing. In the headpiece, Raphael creates an interesting arrangement of varied contour lines playing over the skull. But he is careful to give predominance to the band tied behind at the important plane break of the occipital protuberance (G).

Raphael Sanzio (1483-1520)

DOUBLE STUDY OF KNEELING WOMAN

black chalk

15 9/16″ × 9 7/8″ (395 × 251 mm)

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Rubens has subdued the details of the neck in order to emphasize the face of his model. Lateral inclination of the head or tilting of the head to the side is usually accompanied by rotation toward the shoulder. Here this action of lateral inclination is produced by the simultaneous contraction of the extensors and flexors on the right-hand side.

At the other side of the neck, the long graceful spiral of the trapezius (A) and the upper portion of the sternocleidomastoideus (B) reflect the curve of the backbone. On the inner side, a short curved line suggests the other sternocleidomastoideus (C) bending slightly toward the posterior triangle (D) of the neck, and overlapping the area of the cast shadow, which represents the direction of the upper trapezius (E).

The larger thyroid gland of the female helps soften the protrusions of the throat. In the fullness beneath the jaw and throughout the drawing, Rubens has emphasized the more delicate feminine qualities in his line and modeling.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640)

YOUNG WOMAN WITH CROSSED HANDS

black and red chalk, heightened with white

18 1/2″ × 14 1/8″ (470 × 358 mm)

Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Historically, in their analysis of growth and form and in the search after harmonic mathematical relationships in the shapes of the human head and features, artists and scientists have created a variety of geometric arrangements by which to compare these forms.

The artist knows that in order to create, he must exaggerate reality. But to do this, he must have an idea of what reality is to begin with. Once familiar with the norms or standards, the variations can easily be perceived and played upon. These diverse and only generally accurate artistic canons should be no more than guides and secondary to artistic needs.

Here Dürer experiments with a block or cube, which he divides into a network of rectangular coordinates of seven units horizontally, four equal divisions vertically, with additional subdivisions for the eye and ear.

The ovoid shape of the cranium dominates Dürer’s contructed head. The facial portion of the skull lies below the brows and in front of the ears. Dürer places the high point of his skull (A) above the mastoid process (B), and the wide point (C) at about the level of the glabella of the frontal bone (D).

Note how Dürer ignores his original line (E) in order to give the cylinder of the neck the forward thrust of the spine. The depth line of the neck (F) is four-sevenths the length of the total block, and forms a right angle with the limiting line (G) of the lower face.

With the exception of his enlargement of the area between the hairline (H) or widow’s peak, and the crown (I), Dürer’s breakup follows the traditional three equal divisions between hairline (H) and brow (J), brow to base of nose (K), and base of nose to base of chin (L).

Note how the top of the brow (J) and the base of the nose (K) are horizontally coincident or level with the top and bottom of the ear, and how the front of the eye lines up with the back of the nose.

Had the drawing progressed further in detail, other relationships would have become evident. But it is clear that the artist knows that one secret of likeness lies in comparisons made possible by the use of a structural system such as this one.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528)

CONSTRUCTED HEAD OF A MAN IN PROFILE

pen and brown and red inks

9 9/16″ × 7 1/2″ (243 × 189 mm)

Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

If you want to learn to draw good heads, you must learn to draw good skulls. This drawing by Baldung shows how the head in old age provides a good subject for study of the bony scaffolding upon which the head is based. The effects of time and gravity upon the skin tissues render the facial muscles more obvious and the planes of the face easier to place.

The facial muscles differ from most muscles in that instead of moving one bone upon another, they mostly move the skin. While they may have some attachment to the bones of the face, their insertions are into the skin. The fibers of the muscles of the face tend to converge toward the oral region, the area of the mouth.

Observation shows us that wrinkles form at about right angles to the direction of the muscles that cause them. The prominent nasolabial furrow (A), which separates the wing of the nose from the cheek, forms in a direction contrary to the buccinator (B), zygomatic minor (C), and levator labii superioris (D) muscles.

The horizontal furrows (E) of the frontal eminence are at tight angles to the vertical occipitofrontalis muscle (F). The furrows (E) and the form of the eyebrows (G) below reveal the shape and values of the frontal eminences (H) and the superciliary eminences (I) of the skull beneath. Above this, Baldung places the plane break of the forehead (J), which is broken at the side by the superficial temporal vein (K) commonly seen in the aged.

The infrapalpebraral furrow (L) spirals down along the edge of the “tear bag” (M), extending down to the infraorbital region (N), over the plane break on the malar (O), and down the front of the masseter (P) muscles.

Furrows move like rivers through valleys in the aged faces in master drawings and in the elderly around us. Tracing their course can provide profitable insights into the form and function of the muscles and bones of the face.

Hans Baidung (1484-1545)

HEAD OF SATURN

black chalk

Albertina, Vienna

The superficial muscles of the face are called the muscles of facial expression. Besides influencing our expressions, they also perform major functions such as closing the eyelids, opening and closing the lips, and auxiliary functions during eating and speaking.

The facial muscles greatly vary in size, shape, and strength. They are not always easily distinguishable, as they sometimes exchange their fiber bundles, and they are not all located on a superficial level. They are sometimes grouped in relation to the openings which they modify, such as the orbit of the eye, the nasal aperture, and the mouth. Again, they can be placed by facial region: orbital (A), supraorbital (B), infraorbital (C), nasal (D), zygomatic (E), temporal (F), auricular (G), parotid-masseteric (H), buccal (I), oral (J), and mental (K).

Seeing muscles in terms of similarity in shape—such as the circular orbicularis palpebrarum surrounding the eye, and the orbicularis oris surrounding the mouth—may help you to remember them. In the mental or chin region, it is valuable to contrast the shapes and functions of the depressor anguli oris or triangularis (L), which lowers the corner of the mouth, with the square muscle of the lower lip or the depressor labii inferioris (M), which causes the lip to protrude when you pout.

Fouquet’s heavy-set model is middle-aged, so his wrinkles are not emphasized. Nevertheless, in order to create plane change, the nasolabial (N) and the mentilabial (O) furrows are almost always needed. The “commissural” furrow (P) at the angle of the mouth and the vertical frown line (Q) also help to break the horizontal direction of the adjacent furrows and add a note of seriousness to the face.

Jean Fouquet (1415-1481)

PORTRAIT OF AN ECCLESIASTIC

silverpoint on paper, black chalk.

7 11/16″ × 5 5/16″ (195 × 135 mm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

At the halfway point of the head, the eye sits well within the orbital cavity of the skull. It is protected above by the supercilliary eminence (A) and by the external angular process (B) of the frontal bone. The tear bag of the lower lid (C) lies along the infraorbital margin (D) of the malar or zygomatic bone. Note that the outer corner of the eye (E) sits higher and further back than the inner corner. The eyebrow (F) rides the upper rim of the orbit and the line fades in the highlight as it rises over the external angular process.

The layman tends to see a person in terms of the details of their features. The artist, on the other hand, thinks in terms of the underlying structure of the skull so that the features are positioned correctly on the skull and in relation to each other. This will insure a good foundation for both likeness and perspective.

Dürer treated the lids as ribbons of flesh moving over the sphere of the eye and he made certain that the upper lid just cleared the pupil. The curve of this lid follows the shape of the eyeball to its highest point (G) just above the black spot of the iris that is raised by the transparent mound of the cornea. This upper lid is usually drenched in shadow by the mass above. But since it is an up plane, which normally catches the light, the artist either minimizes this cast shadow, as Dürer did, or eliminates it entirely.

Two little, wet highlights in the dark pupil of the near eye reflect multiple light sources. A dark accent in the iris where it meets the sclera or “white of the eye” (H) gives the gradation of value in the iris, as well as the illusion of the mound of the cornea lying over it.

The near eye is spherical in shape and the little highlights in the iris are side by side horizontally. In the distant eye, the lower lid (I) curves sharply behind the eyeball, and both the sphere of the iris and the highlight within it become ellipses as they move into perspective.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528)

PORTRAIT OF HIS MOTHER

charcoal

16 5/8″ × 12″ (421 × 303 mm)

Staatliche Museen, Berlin

The landmarks of the nose are easily defined in the time-worn face of Dürer’s line and wash drawing. In studying the nose, the artist must first learn something of its basic structure and its parts. He must then examine and compare the sizes, shapes, directions, and positional relationships of these parts. Finally, he can give form and individuality to these parts in his drawing by the way in which he assembles and designs these elements.

The form of the nose depends on the size and shape of the nasal bones and the nasal cartilage. The bony pyramid of the nasal bone (A) runs from the root of the nose (B) just below the glabella (C) to about mid-nose. Dürer clues us to its end by angling it slightly (D) where the bone turns to cartilage. The line moves inward to form half of the septal angle (E) at the midline of the nose. The lower lateral, comma, or alar cartilage (F) curves from behind, creating the wings or alae (G) and the central bulb (H), and then curves over the tip or dome (I), folding back upon itself and helping to form the inner nostril (J). Dürer marks the cleft at the meeting of the two halves of this cartilage by a short line (K).

The septal cartilage that divides the nasal passage under the tip of the nose is not visible on this lowered head, and the curve of the reflected light (L) on the nasal wing is our only indication of the nostrils. Dürer breaks the plane at the tip of the nose (M), on the wing or ala (G), and at the side of the nasal bone (N), where a transitional halftone (O) eases us into the highlight (P).

The horizontal furrow (Q) at the root of the nose forms at right angles to the vertical pyramidalis nasi or procerus muscle (R) at the sides of the bridge of the nose. The compressor nasi (S) lies on either side of the upper lateral cartilage. Tiny dilator and depressor muscles on the wing of the nose also contribute to the form. They become prominent during times of great exertion and in expressions of strong emotions.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528)

STUDY FOR SAINT JEROME (PORTRAIT OF A MAN OF NINETY-THREE)

brush and black ink, heightened with white, on gray violet tinted paper

16 1/2″ × 11 1/8″ (420 × 282 mm)

Albertina, Vienna

The oral region includes the mouth, the teeth, and the tongue. The obicularis oris muscle (A) circles the mouth, creating the thickness of the lips. The outer surface of the lips (B), called the red margin or vermillion zone, varies greatly in individuals. It is generally thicker at the middle tubercle of the upper lip (C), which forms the central section of the lip. Both lips taper to meet the corner or angle of the mouth (D).

The upper lip extends to the base of the nose, out to the nasolabial furrow (E) at the edge of the buccal region of the cheeks (F), and down to the opening of the mouth. The line of this opening and the mass of the upper lip form a cupid’s bow, a shape that curves around the cylinder of the mouth following the curved form of the teeth. If you divide the distance between the base of the nose and the base of the mental eminence or chin (G) into three parts, you will note that di Credi has placed the slit of the mouth at the upper third division.

The highlight (H) runs along the rim of the upper lip on the long, thin, light area called the new skin. It curves down at the center to accentuate the shallow vertical groove of the philtrum (H), the groove above the cupid’s bow. In the lower lip, the highlights in the top plane follow the contour of the skin creases. Small highlights (I) at either end mark its outer limit at the angle of the mouth (D), and a dark accent (J) below shows the down plane where the lower lip meets the mentilabial furrow, the groove between the chin and lip area.

The central fibers of the obicularis oris (A) close and compress the mouth, and its outer fibers project the lips forward, as in pouting. Superficial and deep muscles converge upon the obicularis oris from all sides to raise, lower, and expand the lips, and to contribute significantly to the range of facial expressions.

Lorenzo di Credi (c. 1458-1537)

HEAD OF A YOUNG MAN

black chalk and ink on pink paper

7 1/8″ × 5 3/8″ (180 × 138 mm)

Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam

This page of features delicately drawn by Michelangelo provides a good example of the auricle or external ear. The ear is connected to the skull by ligaments and muscles and consists of cartilage shaped for the collection of sound waves. Seen in profile, it lies behind the center-line of the head, behind and above the ramus or vertical portion of the jawbone, and above the mastoid process of the temporal bone of the skull.

The curved outer rim of the ear is called the helix (A). Inside this is the broader, curved ridge of the antihelix (B). In its upper and forward portion, the antihelix forms two separate ridges, called the crura (C), which create a small triangular fossa or depression (D).

Michelangelo places a large area of darks in the deep cavity of the lower ear, called the concha (E), that lies in from the lower portion of the antihelix (B). This area is bounded in the front by the small prominence of the tragus (F). The tragus, from which grow fine filtering hairs, overhangs the small black area that marks the opening of the auditory canal (G), leading to the inner ear. Another small tubercle, the antitragus (H), is the cartilage that sits opposite the tragus; the two are separated by the intertragic notch (I). Below this notch lies the soft oval form of the lobe (J).

The auricular muscles lie above, in front, and behind the ear, and help maintain it in its position on the skull, but otherwise are of little use to artists. Michelangelo has placed a slight angle in the long curve of the helix at the slight rise of the Darwinian tubercle (K). This evolutionary leftover represents the extreme point of the very movable ear that we can still observe in animals such as the horse.

Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564)

SKETCHES OF HEADS AND FEATURES

pen and ink

8 1/4″ × 10″ (206 × 255 mm)

Kunsthalle, Hamburg

In order to master the finer gradations of human expressions, a careful study of the muscles of the face is of great importance. It is helpful to examine Leonardo’s five heads, which suggest a graduated series of emotions ranging from a pleased countenance, through grinning and smiling, to violent laughter.

The man with the bald head, which is crowned with oak leaves, gives the appearance of self-satisfaction. The head is upright with no inclination and the central fibers of the orbicularis oris (A) compress the lips firmly. The strong contrast between the pupil and the iris give the eye the bright sparkle of a pleased or bemused state of mind and the “crow’s feet” (B) at the corner of the eye suggest his tendency to smile frequently.

The head on the lower right exhibits a stubborn grin activated by the risorius muscle (C), with little expression about the eyes. It is a short step between this expression and that of the grinning woman at the extreme left. Here the risorius (C) together with the zygomatic major (D) and the zygomatic minor (E) muscles pull the lips back and upward. This deepens the nasolabial furrow (F) and, with the orbicularis palpebrarum (also called the orbicularis oculi) muscle surrounding the eye, causes wrinkles to form at the corners of the eye (G).

The figure in the background at the upper right suggests a false smile. The angles of his mouth are spread by the risorius (C) as in a very wide grin. In a true smile, the action of the two zygomatic muscles (H) and the lower portion of the orbicularis palpebrarum muscle (I) would have raised the nasolabial furrow (F) much higher, causing crow’s feet to form at the corners of the eyes. Above all, the action of the corrugator muscle (J), causing a vertical frown crease, reveals the falseness of the smile. The corrugator never acts under the influence of joy.

At the end of the sequence, the figure on the upper left is in a state of violent laughter. His head is thrown back, his mouth is opened to its widest point, and his upper lip is raised in a grin that exposes his teeth.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

GROUP OF FIVE GROTESQUE HEADS

pen and ink

10 1/4″ × 8 1/2″ (260 × 215 mm)

Reproduced by gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen

Royal Library, Windsor

The expressions of contempt, scorn, disdain, and disgust are expressed in many variations of facial movements, as well as by gestures of the head and limbs that represent rejection of something or someone.

Poussin depicts himself wearing a strong expression of disgust. Contempt, scorn, disdain, and disgust are merely variations in intensity of related emotions, since their combinations of muscular movements are similar. The most common means of expressing contempt is by movements about the nose and mouth.

In Poussin’s drawing, there is a slight lifting of the nose by the pyramidalis nasi or procerus (A) and the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (B), causing the wrinkle that forms at the root of the nose. This is usually accompanied by a slight, snarling, upward movement of the upper lip with the assistance of the caninus (C), as if to display the canine tooth. In the expression of disgust, the nose is slightly constricted by the depressor alae nasi (D) which partly closes the opening, as if to exclude an offensive odor.

The angle of the mouth is moved downward in displeasure by the action of the depressor anguli oris (E). The zygomaticus major (F) pulls the upper lip and cheek backward and up, deepening the nasolabial furrow (G).

The skin of the forehead is drawn downward and wrinkled by the frontalis (H) and the corrugators (I) of both sides, adding to the frowning appearance.

The eyes stare contemptuously ahead, and the emphasis on one sternocleidomastoideus (J) indicates that the head has just turned to direct the gaze at the object of dislike.

Nicholas Poussin (1594-1665)

SELF-PORTRAIT

chalk

British Museum, London

Most artists have observed the transformations of the features of the face as the expressions graduate from sudden attention to surprise, admiration, astonishment, fear, and finally, to horror. In Pontormo’s study, the subject is at the attention stage. The brows are strongly raised by the occipito-frontalis muscle (A) to allow the eyes to rapidly open wide in order to quickly perceive the cause of attention.

The mouth of Pontormo’s subject has not opened as it would in astonishment, but is compressed as in thought. This facial gesture is reinforced by the vertical frown line (B) suggesting the action of the corrugator supercilii (C), the muscle of reflection.

The two wisps of hair (D) that echo the curves of the brow and eye and draw attention to the ear suggest that the model is listening intently to an unidentified sound. Our interest in this area is further reinforced by the nearly parallel lines of these two spirals of hair.

In fear, the chief play of muscles is seen in the areas of the eyes and the mouth. As attention turns to fear, the jaw drops, the mouth opens, the eyes widen, and the pupils dilate.

As fear turns to horror, the platysma myoides muscle, which spreads over the surface of the side of the neck from mouth to shoulder, is strongly contracted. This further draws down the angles of the mouth and produces deep oblique wrinkles in the neck.

Jacopo Pontormo (1494-1556)

STUDY OF A PORTRAIT OF PIERO DE’ MEDICI

red chalk

6 3/16″ × 7 13/16″ (157 × 198 mm) Uffizi, Florence

The corrugator supercilii (A) is the muscle of troubled reflection. In Bellini’s old man, by its contraction, this muscle “knits” the eyebrows by drawing them inward. It helps convey the impression of deep thought, as well as some difficulty or disturbance to the tranquil state of mind.

The model’s slightly opened mouth suggests an element of pain, exhaustion, and resignation. The despair of long suffering expresses itself in actions opposite to those that produce laughter. There is a relaxation, not only of the muscles of the face, but of the whole body. The jaw drops, the mouth opens, and the angle of the mouth (B) droops downward. There is a general sagging around the cheeks and eyes.

The familiar “crow’s feet” wrinkles (C), the wrinkles in the upper eyelid (D), and the wrinkles in the area of the frontal eminence (E) suggest frequent activity of the obicularis palpebrarum (F) that surrounds the eye and the vertical frontalis muscle (E) above.

With the increase of grief, the whole frowning brow is drawn further down by the vertically placed pyramidalis nasi (G) on either side of the nose, causing the horizontal wrinkles (H) at the root of the nose.

Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430-1516)

HEAD OF AN OLD MAN

brush on blue paper, heightened with white

10 1/4″ × 7 1/2″ (260 × 190 mm)

Reproduced by gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen

Royal Library, Windsor

The rage of Michelangelo’s “Fury” is an intensification of the simple, sneerlike defiance, when a threatening canine tooth is exposed by drawing up the upper lip. The mouth of the raging “Fury” is opened wide. The lips are drawn to the sides and upward causing the deepening of the nasolabial furrow (A) and the jugal furrow (B) of the cheek bone.

One dominant vertical strand of muscular fiber (C) clues us to the contractions of the platysma muscle which covers the front and side of the neck. This muscle shows in times of rage, great fright, nausea, or disgust. The anterior portion of the platysma draws down the inferior maxillary in order to open the mouth, and it aids in drawing down the lower lip and the sides of the mouth.

The sternocleidomastoideus (D) stands out as the head is turned to face the antagonist. The swirl of the surrounding drapery both accentuates this action and harmonizes with it.

The entire upper lip is retracted by the levators (E), exposing a row of teeth, as if to bite the opponent. The upper lip and the wing of the nose move upward. The nostril is dilated by the anterior and posterior dilator naris muscles (F), permitting greater intake of air in preparation for strenuous action.

The orbicularis palpebrarum (G), the corrugator (H), and the pyramidalis nasi or procerus (I) depress and contract the brows, causing deep central furrows (J) and wrinkles over the bridge of the nose (K).

The bristling of hairs (L) associated with violent anger is caused by contraction of the frontalis muscle (M), these movements intensifying the overall agitation of the curved lines in the drawing.

Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564)

DAMNED SOUL, A FURY

black chalk

11 5/8″ × 8″ (295 × 203 mm)

Uffizi, Florence

Many methods have been devised for measuring the human figure. The units of measurement have ranged from the length of the middle finger used by the Egyptians, to the length of the palm of the hand of the Greeks, to the eight-headed figure of Vitruvius, to the five-eyed width of the head used by Cousins, to the seven-and-a-half heads of the Canon des Ateliers advocated by Richer that is very much in use today.

In the study of proportions, the artist seeks keys to harmonic relationships in nature. The ancient Greeks applied knowledge gained in the study of the human body to the construction of the Parthenon. Like the body, the Parthenon is a harmonious unit in which the component parts function in balance with the whole, and yet deviate from absolute mathematical regularity in order to correct optical illusions.

Since individuals vary so greatly, it is impossible to lay down absolute rules on proportions. And with every movement of the body there are changes in perspective and foreshortening that also frustrate attempts to measure the body visually. So a set of rules on proportions can never be more than a guide. But organizing the body in a logical way can help to clarify relationships between its parts.

Leonardo used the seven-and-one-half-head measurement in this drawing, though he often deviated from this measurement, as did Dürer and the other great masters. He knew that the traditional measuring points of the nipple, navel, and genital organs were not fixed points, but only guides from which he could create individual modifications.

All great master drawings will show deviations from basic structure. Once the standard measurements, landmarks, memory devices and other clues have taught you to observe and compare, you can safely put them aside and follow your own creative impulses.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

MALE NUDE FACING FRONT

red chalk on red paper

9 1/4″ × 5 3/4″ (236 × 146 mm)

Reproduced by gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen

Reproduced by gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen

Royal Library, Windsor