Corpsmen, or medics—enlisted men trained to provide first aid on the battlefield—were vitally important to a combat unit. The medical help they gave to wounded men often meant the difference between life and death. The efforts of the corpsmen and medics, combined with quick helicopter evacuations known as “dustoffs,” considerably lowered the death rate among U.S. combat casualties. The enemy recognized how important they were to a unit and specifically targeted them. Lee Reynolds, an army corpsman, said, “The VC were paid an incentive to kill a medic.”

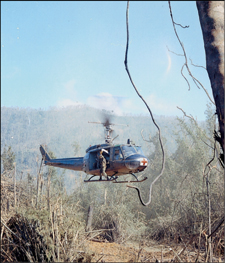

A Huey with a red cross, signifying that it is an unarmed medical helicopter.

Corpsmen were among the most fearless men in combat. During a fire-fight, they could be seen crawling or rushing to help wounded men, heedless of the danger to themselves. Ralph Daniello was a navy corpsman assigned to a marine unit at Khe Sanh. Of his experience he later recalled, “I remember going through firefights, getting hit, and taking care of the wounded, and your hands are full of blood, and you wipe them off on your pants. After days and weeks of wearing the same clothes, your pants are still stiff from the blood.”

Wayne Smith was an army combat medic. He later recalled, “Combat was horrible, but there was a beautiful side as well—the brotherhood between black soldiers and white soldiers and Hispanics and Native Americans. When we were in combat, all that mattered was trying to survive together. . . . In combat all that matters is: Are you going to do your duty and [help me] when I get hit? . . . I was eighteen and knew a little about how to save lives. . . .” His skills were put to the test during one operation in the Plain of Reeds near the Cambodian border. One of the soldiers tripped a booby trap called a “daisy chain”—a series of grenades strung together. Smith rushed forward to save the wounded. One soldier had one of the worst battlefield wounds possible—a punctured lung that produces what’s called a “sucking chest” wound. He managed to save the life of that soldier. He later said, “If you don’t panic, it’s not hard, but you always have that fear of [making a mistake] and causing someone to die. There’s nothing worse than that for a medic.”

Thanks to the high quality of training that medics and corpsmen received, the mortality rate for wounded was, when compared to prior wars, an astonishingly low 1 to 2.5 percent, the lowest rate ever.