In the beginning of the Vietnam War, most news was told by reporters and photographers working for newspapers, magazines, or the syndicated wire services. Before the invention of modern conveniences such as fax machines and cell phones, writing and filing stories was a time-consuming task. Reports were filed through the government-controlled telegraph office, by courier, or sometimes by phone. Phones themselves were rare and unreliable. The Associated Press office in Saigon had only one phone—a battered, heavily taped device that was as priceless as it was fragile.

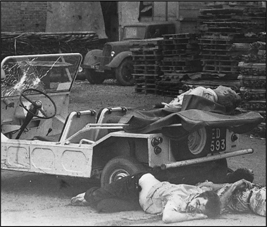

Newsmen killed in Saigon by Viet Cong guerrillas.

But as the war progressed, it was television journalism, then in its infancy, that came to dominate war reporting. The first television crews were at a great disadvantage compared to today’s crews. Equipment was bulky, heavy, and by today’s standards, crude. Crews of three men carried a camera that weighed as much as fifty pounds. Even so, ultimately, television’s graphic, moving pictures of burning villages, dead bodies, blood-covered soldiers and civilians, and panic-stricken children would bring the war into Americans’ living rooms. In the United States, the immediacy and the vividness of television reports would profoundly affect opinions about the war.

The quality of the journalists ranged from the brilliant to the totally ignorant. Pulitzer Prize–winner Eddie Adams noted once that “[y]ou had a lot of adventure seekers.” In the most extreme cases Saigon-based journalists would rush to the battle scene invariably after it had ended, spend a few hours there, and then return to Saigon to file their stories.

Joe Galloway of United Press International was one of a handful of reporters who accompanied combat troops onto the field. Galloway was the only journalist who was with Lt. Col. Moore and his men during the Ia Drang campaign. At one point during the fighting, Galloway recalled, “The incoming fire was only a couple of feet off the ground, and I was down as flat as I could get when I felt the toe of a combat boot in my ribs. I turned my head sideways and looked up. There, standing tall, was Sergeant Major Basil Plumley. Plumley leaned down and shouted over the noise of the guns: ‘You can’t take no pictures laying down there on the ground, sonny.’ . . . I thought: ‘He’s right. We’re all going to die anyway, so I might as well take mine standing up.’ I got up and began taking a few photographs.” Galloway survived that action and went on to become a highly respected reporter of the Vietnam War.