Al Kooper had assembled the band at Studio One back in June 1973, a month after the pronounced album sessions had concluded but before Kooper’s party at Richard’s, to record a song that Ronnie swore to all that was holy just had to be a hit. It had come about a few weeks before at Hell House from a riff Ed King liked to say came to him in a dream but that, he says now, really began with him joining in on an idle Rossington riff. The way Ronnie incubated a song, King had come to learn, was most unusual. When such a riff was played for him on a guitar or piano, his brain would go into overdrive, but the others in the band wouldn’t know until he had a microphone before him what he would sing.

“I never saw him write a lyric down,” says King. “It was all in his head, based on the groove. If you ever showed up at rehearsal the next day and couldn’t recapture the groove—you might have the chords right, but if you’d lost the groove—the lyrics were gone forever. One time he said, ‘I can’t remember it.’ We go, ‘What happened?’ And he said, ‘You guys lost it, man.’ So you know, that song was gone. But that didn’t happen anymore. We’d stay there till dark, playing stuff over and over until we were playing it in our sleep. No wonder that solo came to me in a dream, because we just played and played and played.

“Listen, Ronnie Van Zant really wasn’t a redneck. He was a very sophisticated guy. I mean, people think he was just this rowdy, whiskey drinking, going out, gathering other women, but Ronnie had a level of sophistication that even early on just grew so fast. Every day you’d see a change. So I wouldn’t, didn’t even classify him as a redneck. But the thing about him that appealed to everybody is you could tell by listening to him sing that that’s exactly what he was like in real life. I mean it’s exactly him. All you had to listen to was six Skynyrd songs, and then you’d have the whole gist of what that man was about.”

“Sweet Home Alabama,” as this one was called, coalesced when King locked into Ronnie’s lyrical progression, which from somewhere deep in Ronnie’s thought process developed as an answer to Neil Young’s scalding couplet of Dixie ragging, the 1970 “Southern Man” and 1972 “Alabama,” eviscerating all southern men who didn’t explicitly condemn the vestige of their “heritage” that had caused black men to hang from trees on nooses. “I saw cotton and I saw black,” Young had sung on the former, a huge hit, “tall white mansions and little shacks. Southern Man, when will you pay them back?” In the latter song he further mocked the hypocrisy of men not compelled to “do what your good book says”: “You got the rest of the union to help you along / What’s going wrong?” Ronnie, who thought such generalizations ignored the obvious debt being paid to black music by country rock bands like his, decided to pay back the man he greatly admired. Indeed, he came to regard Young’s 1972 smash “Heart of Gold” as a template, with its mourning slide guitar and thumping beat. He had a drawer full of Young T-shirts, which he often wore on stage and would continue to.

Ronnie, in fact, was squeamish about taunting Young. He later recalled that “I showed the verse to Ed and asked him what Neil might think. Ed said he’d dig it; he’d be laughing at it.” And so he went on, repaying Young in kind, his lyrics just as stinging, sticking up for southern manhood. There was some soft soap too about the rush of being carried home “to see my kin” and the peerless Swampers up in Muscle Shoals, who’ve “been known to pick a song or two.” But then there were the references that at first listen seemed affectionate about George Corley Wallace—“In Birmingham they love the Gov’nor”—followed by the most cryptic sequence of stray thoughts ever in rock: “Boo! Boo! Boo! We all did what we could do. / Now Watergate does not bother me, / Does your conscience bother you? (Tell the truth!)”

Just what this all meant was anyone’s guess. Indeed, the references were in some ways outdated or predated. Wallace at the time was not quite the roaring lion. He was recovering from the near-fatal wounds he had suffered while campaigning for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination, when the drifter Arthur Bremer shot him five times at a Maryland shopping center. After a hospital stay, Wallace returned to the governor’s mansion, no less adamant in his support for, as he once infamously said, “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Even in a wheelchair, he was still a hoary segregationist.

The reference to Birmingham was pointed, but it had been a decade since the city had witnessed the horrendous Ku Klux Klan church bombing that had killed four black girls—way back in 1963. As for Watergate, Ronnie was behind the curve. The scandal had grown and was closing in on Richard Nixon. The lyrics, then, were a weird hash of scattered, unfocused thoughts, something not surprising given that Ed King describes Van Zant’s writing process as less than disciplined. “Basically,” King says, “Ronnie didn’t think real hard about what he was writing. He wrote from his heart; he was a guy who wrote his feelings into songs.”

Artimus Pyle, after he later joined the group, believed he could play it with more conviction on the drums if he knew what Ronnie had in mind. As Pyle recalled, “Ronnie explained it to me he was telling the Southern Man that the Southern Man is not to be blamed for something that happened two hundred years ago. He was saying, ‘I don’t have anything against African American people,’ and Ronnie didn’t. He’d give the shirt off his back to anybody, black or white. Ronnie was not a racist.”

Extrapolating all that from the lyrics of this song is impossible, and to be sure, Pyle would have more than one fanciful explanation about Skynyrd matters big and small. For his part, Rossington, believably, says that the picking of a fight with Neil Young was “completely fabricated. We all loved Neil. Ronnie used to wear Neil Young T-shirts all the time because he loved him and was really inspired by him. He just wrote those lines about ‘Southern Man,’ which seemed cute at the time, almost like a play on words.” But the constructions that began to take hold about the overall intent of “Sweet Home Alabama” would not be so easy to dismiss as innocuous folderol.

While cutting the first vocal take of the tune, Ronnie, having trouble hearing the rhythm track in his headphones, instructed engineer Rodney Mills to “Turn it up!” For Kooper this must have brought back fond memories of playing his impromptu organ line on “Like a Rolling Stone,” one that the record company executives in the studio hated but were overruled on by Bob Dylan barking, “Turn the organ up!” Perhaps feeling sentimental and because it caught Ronnie’s sense of conviction, he left it in, prefacing King’s prickly guitar intro, which repeated through the song—and which would be, ahem, appropriated four years later by Joe Perry on Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way.” So profound was King’s riff that the Fender Stratocaster he used that day, the same one he’d originally played the riff on at Hell House, is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame—despite the fact that King liked it least of all his guitars. “It was a horrible guitar,” he later said. “It was the banjo-like tone that prompted Ronnie to write about Alabama, like ‘I come from Alabama with a banjo on my knee.’ But I still hated it.”

Kooper also got into the swing when, after the opening lines about hearing “Mister Young” sing about the South, the producer sang a line from the Young song—“Southern man, better use your head”—in harmony. Ronnie didn’t care for it, but Kooper left his rendition in, though he mixed it so low that it was “nearly subliminal,” he says. The band played at a honky-tonk blues pace, the three guitars pealing high and twangy, so sharply recorded by Kooper that they could tear off one’s eyebrows. Prepared and on target as they were, they nailed it in one take, though Ronnie, who never liked anything the first time he heard it, demanded a second take to make sure. And Kooper wasn’t through with it yet either. When he and the band went out to the coast for the Who tour, he brought the tape of the song so he could continue tweaking it, including adding a horn overlay at an L.A. studio. He also hired a trio of female soul singers, Merry Clayton, Clydie King, and Sherlie Matthews—proof enough to some that the song was hardly a celebration of Old South racism—to juice up the hooks; this was the second song of note Clayton would dress up, having sung a withering harmony with Mick Jagger and the unforgettable solo about “rape and murder” being just a shot away on “Gimme Shelter.”

Finally calling it done, Kooper had in hand a fisty, smug, funky, hard-rockin’ ode to the New South struggling to get out of the shadow of the Old Confederacy. With its clever and catchy title hook, a listener could get lost in a dreamy milieu where “the skies are so blue” and the words “Lord I’m coming home to you” could make it actually feel like the South was one’s home, anyone’s. But those throwaway lines about the “Gov’nor” and the most stigmatized of all Southern cities were going to be heard too—loud, if not exactly clear. Kooper was sanguine about it. “I think they were proud of where they came from,” he said breezily. “Racism didn’t come into it.” Still, he had to admit that lines like “We all did what we could do” were “ambiguous.” And even Ed King says he didn’t know what Ronnie meant by it, especially in relation to Watergate. Kooper’s interpretation of that line somehow was: “We tried to get Wallace out of there,” although nothing in the maddeningly ambiguous song supported that point of view.

Feeling so good about the tune, as well he should have, Ronnie did not forget his promise to Jimmy Johnson. That night he called Muscle Shoals. “Hey, man,” he told Johnson, “we put you guys in a song.”

Johnson was duly flattered but had to wonder: Would anyone ever hear it?

Ronnie had no doubts about it. “Well, Ed,” he told King when they wrapped up recording, “that’s our ‘Ramblin’ Man.’”

“Gimme Three Steps” was released in November, backed with “Mr. Banker,” one of the Kooper demo tapes that hadn’t made it onto the album. Although the band was a hit out on the Who tour, the single made little penetration, failing to crack the charts or rouse concert audiences. Clearly, as a light-hearted pastiche of redneck life, it was more suited to be a change of pace after a hoped-for string of hits. Indeed, the buzz about Skynyrd was centered on “Free Bird,” which was igniting audiences, and “Sweet Home Alabama,” which they made sure to perform at every show and which etched their identity. The amazing thing was how tight the guitars were, how spectacularly they meshed, and how close to the Kooper studio versions these live performances were, confirming Kooper’s initial conviction that he had never run across a band as polished and rehearsed to perfection as this one. On “Alabama,” absent background singers, Leon stepped forward from his usual place hanging around the rear of the stage to execute a harmony vocal, something that delighted Ronnie once he learned that Wilkeson actually had a decent singing voice.

Having sung “Free Bird” hundreds of times already, Ronnie had developed a routine for what could be up to ten minutes of guitar onslaught. Having remained true to his vow never to try any hip-swiveling moves or flounce around like the bare-chested, Spandex-and-fringe-wearing front man of the hugely successful Black Oak Arkansas, Jim “Dandy” Mangrum—not that he could with all the beer he put in his gut—Ronnie would float between the guitarists or merely hang back by the drum, digging the groove. In his hat, jeans, and bare feet, he was still a riveting, engaging front man, even doing nothing.

Kooper and the MCA boys were satisfied. They had cautiously set a target sale level for the album of four hundred thousand copies, and with gathering momentum it had cleared one hundred thousand by the end of the year, which was punctuated by a show the band headlined in Atlanta at the Sheraton Biltmore that sold out its five thousand tickets and was a success even though the power went down for a few minutes during the set. They met up with Kooper at the Record Plant in Burbank with a full sheaf of new songs for the second album—though at first glance their visit might have been confused with a getaway at a spa. The studio was one of three with the same name, the others being in New York and Sausalito, California—all owned by Jimi Hendrix’s former recording engineer Gary Kellgren and Revlon cosmetics executive Chris Stone. A radical departure from drab “dentist-officey” studios, as Kooper put it, the L.A. Plant was like the Playboy Mansion with recording gear. With a Jacuzzi room, three plush bedrooms, and hordes of nubile young women everywhere (and clothing purely optional), it was little wonder the Plant was the studio among the big L.A. bands.

Indeed, when the Skynyrd sessions commenced in one studio, the Eagles were in another cutting their magnum opus Hotel California, and the two bands mingled during breaks that were more like playtime. This was decadence of the highest order and lowest instinct, something the Eagles’ Don Henley and Glenn Frey wrote and sang of in their new work but which Ronnie would claim was a turnoff to the Dixie boys more accustomed to back porches and fishin’ hole contentment. He too would write of the L.A. mise-en-scène, not as a magnet but a mine field. None of the Skynyrd boys felt much like prowling the back alleys of Sunset; instead they spent almost all their time in the studio or in the Jacuzzi between takes, snorting piles of cocaine.

The growing success of the debut Skynyrd album gave Kooper more leeway, and his budget for the new album was upped to around $30,000. The band kept faster company now as well, a fact that was underscored when during the sessions John Lennon, during his three-year “lost weekend” separation from Yoko Ono, dropped into the studio and hung out (though in his perpetual drunkenness he may not have known who he was, much less this band from the South). By comparison, Skynyrd was all business. They had come in with seven songs well thought out, arranged, and rehearsed to perfection at Hell House. Kooper, looking for the same formula as that of pronounced, was amazed at the versatility of material before him. In a real tour de force, they gassed up Oklahoman blues troubadour J.J. Cale’s 1972 ballad “Call Me the Breeze” into slick, loud, foot-stomping biker-bar blues, with sizzling solos by Rossington on slide guitar and Powell on piano. Another eye-opener was “The Needle and the Spoon,” a Van Zant-Collins tune confronting the bane of heroin, with Ronnie’s vocal cutting to the bone:

I’ve been feelin’ so sick inside

Got to get better, lord before I die

Seven doctors couldn’t help my head, they said

You better quit, son before you’re dead.

They also had written their best pure blues song, the Van Zant-Collins original “Ballad of Curtis Loew,” in which Ronnie spun a fictitious yarn about selling soda bottles as a boy to pay to hear “an old black man with white curly hair” play his “old Dobro.” That man, given the name Curtis Loew, was a composite of the great Delta guitar masters and “the finest picker to ever play the blues.” Kooper kept the arrangement to a minimum, with Ed and Gary alternating on slide and Al playing piano and acoustic guitar and singing backup vocals.

For the first two weeks, with no gigs to get in the way of recording, they raced through the album. Kooper found a place for the parody riff he liked so much, “Workin’ for MCA.” Besides “Sweet Home Alabama,” a good candidate for release as a single was “I Need You,” a valentine from Ronnie to Judy—and to Paul Rodgers, given that the tune was intended to be the album’s Free soundalike. “What more can I say / Ooh baby, I need you / I miss you more everyday,” he crooned as sinewy multiple guitars rang behind him. Every song seemed to come up a winner. Another, the Van Zant-King “Swamp Music,” was a heartfelt wish to flee “them big ol’ city blues” and spend long days huntin’ ’coons with hound dogs, and it throbbed to the beat of Eric Clapton’s “Lay Down Sally.” Al Kooper was pleased to note that no attempt was made to do “Free Bird II.”

The album, called Second Helping, rounded out the rough edges of pronounced, an objective that could be seen in the cover art. The bone design of the Skynyrd logo was smoothed into more of a Flintstones look than a Black Sabbath one by mod artist Jan Salerno. In a psychedelic, pastel-colored Peter Max-style collage Salerno inserted the band’s rotogravure faces into something resembling a church window or a honeycomb around which were images of birds’ wings and leaves that could have been cannabis. The jacket sleeve had individual black and white, Scavullo-esque shots in various cool poses, and one of the group tossing Kooper into a pool during a birthday party at his house. They did manage to throw in some satirical, frat-boy touches, listing among the album credits a string of pseudonyms—Wicker, Toby, Cockroach, Moochie, Punnel, Wolfman, Kooder, Mr. Feedback, and Gooshie—the band’s pet names for each other, Kooper, the soundman Kevin Elson, and chief roadie Dean Kilpatrick. “Wicker” was Ronnie’s nickname, one that stemmed from, Ed King says, “the name of a gay guy in a movie.” Van Zant liked how it sounded and adopted it, daring anyone to infer he was gay. That would have been dangerous to someone’s health, for sure.

Images aside, there were deeper issues to be resolved. As Kooper recalls, “I sent them the mix, and they went bonkers. Too much cowbell here, not enough vocal there.” Fighting a deadline for the album’s release, he took the tapes to the Record Plant in Sausalito to mix, aided by Ed King who came up just days before a six-day Skynyrd run at Whisky a Go Go. When Ed arrived, he found Kooper in a house provided by Stone and Kellgren, which was crawling with drugs and bouncy young things. King, who came up with his wife, was disgusted. Once, when Kooper was playing music in his bedroom at ear-splitting levels in the middle of the night, King walked in and tore the arm off the record player. Another time, seeing Al and a friend snapping pictures of a naked woman, King, as Kooper recalled, “just walked outside shaking his head.”

Despite all this, what they finally came out with was another remarkable piece of vinyl, one that Rolling Stone retroactively observed “served up the band’s feisty hard-rock twang to a broad national audience.” Stephen Thomas Erlewine of Allmusic.com regards Van Zant’s work on this album as a tour de force, “at turns plainly poetic, surprisingly clever, and always revealing” and credits him for “developing a truly original voice.” In Crawdaddy!, Bud Scoppa wrote that the album “cannily and positively draw[s] a distinction between Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers, a key distinction for them.”

As big a gift as Kooper had in “Sweet Home Alabama,” he decided to hold it back, not, he insists, out of any risk the band would be stereotyped as too regional but because he wanted it to be a killer follow-up to a first hit. Thus the first single was “Don’t Ask Me No Questions,” written by Van Zant and Rossington on a fishing trip, always a head-clearing interlude, that had Ronnie hating on the pressures of the record industry; integrating that theme into a typically macho dismissal of a suspicious woman’s inquiries about where he’d been, he sang with his best sneering arrogance, “Don’t ask me no questions and I won’t tell you no lies / So don’t ask me about my business and I won’t tell you goodbye.” Kooper put a lot into the song, including a full horn section with longtime Rolling Stones sax man Bobby Keys, and played piano and sang backup. The single went out on the market in April backed with “Take Your Time,” a song that had been left off the album; and amid a heavy ad campaign Skynyrd set sail on another long, long trek called the Second Helping Tour.

But while the album began to sell well, the single failed to chart. And the tour itself was becoming something of a bummer as well, the high point being perhaps when they played Nassau Coliseum on February 25, the first time they’d been back on Long Island since the Black Sabbath fiasco. This time, they were the headliner, and the sold-out show went perfectly. Fortuitously, the schedule then took them to their home turf, playing gigs around the South, for the next month and a half. But they needed a jolt, lest they become yet one more band with promise who simply couldn’t cut it in the marketplace. As it happened, they had the jolt they needed in their hip pocket—“Sweet Home Alabama” had become even more of a fan favorite, available on record, and was getting more airplay from the disc jockeys than “No Questions.” Now, Kooper knew, it had to come out as a single, and the future of the band was riding on it.

“Sweet Home Alabama,” with the flip side again “Take Your Time,” hit the stores on June 24, 1974, and began to scramble up the chart, stopping at number eight on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in late summer. On its way up, it did more than give Lynyrd Skynyrd its first and only Top 10 hit. It unfurled the symbolic pennon, and the accompanying baggage, that they have carried ever since. Even before it was released as a single, it had become their virtual theme song out on the hustings, so it was only logical to develop some sort of stage atmospherics to help frame it as such. Thus came the entrance of the highly contentious monogram that still causes delight and consternation to this day.

There is no agreement about who exactly made the decision to pin the literal Confederate flag on Skynyrd’s figurative hide. After it began to appear, it drove redneck fans into a frenzy and nonrednecks into a state of revulsion that an American band had adopted this long-shunned symbol of intolerance at a time when de facto segregation was still extant in the South. When the sharp divide became apparent, Ronnie was not prepared to fall on a Confederate sword—not when it might cut to pieces Skynyrd’s carefully crafted mainstream appeal. Finding a convenient fall guy, he put the blame squarely on the bosses. The flag, he said, was “strictly an MCA gimmick … you know, Southern band, drunken fighters and all that. They put out that publicity. Hype, nothin’ but hype.”

Gary on the other hand maintained that the flag entered the picture as a result of their corporate owners not caring much about contributing any ideas or angles for the band to use. “MCA didn’t promote us,” he said. “We promoted us. We were from the South and our audience always had rebel flags, flying ’em and putting ’em on stage. One night we just said, ‘Hey, let’s just get a big one and put it behind us.’ It was just that simple. We didn’t mean nothing by it. There was no meaning; like the flag means this, or we’re against blacks. We’re just from the South. It wasn’t no big thing to us, it’s not a ‘Hell no, we ain’t forgetting, let’s be rednecks’ kind of thing.”

Although Alan Walden boasted that he and Mike Maitland had sat down and put together a “brilliant marketing plan” for Skynyrd, neither took ownership of the flag idea. Putting the onus back onto the band, Bob Davis, an executive at MCA Records who in the 1980s became vice president of the label, said, “I don’t [believe] that MCA as a company, from a policy point of view, was in any way involved in decisions as to stage presentation, whether or not Confederate flags or anything were part of the presentation of the live show. That being said, that doesn’t mean there were not people out in the field, whether they were sales or marketing people, promotion people, who weren’t making suggestions … in connection with marketing a record.”

Those people would have had a great influence on a fairly wide-eyed band in the maw of free-wheeling, free-ranging record company lackeys, either under contract or as loosely affiliated promotional leeches and lemmings—think Artie Fufkin, Paul Shaffer’s bumbling record-company stooge in This Is Spinal Tap. People just like that swarmed around bands on the rise, meeting them backstage or in hotels looking for an in, the pockets of their faux-satin baseball jackets stuffed with envelopes of cocaine. Not only were such supplies liberally dispensed to Skynyrd, fueling their descent into an addiction inferno, but the yes men, amoral as they were, eagerly endorsed the Confederate flag as a marketing tool, on the assumption that racism could be cool.

Certainly, Skynyrd needed something to enliven a rather static onstage persona. Davis thought they were “very bland” and wanted to add pizzazz. And Al Kooper had perhaps unwittingly opened the door for something more daring than an image of long-haired rednecks when he applied the skull-and-bones motif to their album and subsequent promotional materials; soon T-shirts with that motif were selling quite nicely at arenas. Adding one more promotional tool might put them over the top, and it surely made sense to some at the record company that the Stars and Bars conveyed some sort of nativist pride, if seen in the narrow context of southern “heritage.” When Skynyrd would enter the stage to “Dixie” playing through the hall and a giant Confederate flag covering the entire back wall, there was surely a surge of regional pride in the air—but also a surge of anger.

This helped them in the South but elsewhere left a decided unease and instant revulsion. For many African Americans and for northern liberals, including the most respected music critics, the flag was tantamount to a swastika, and defending it was a very tricky business, as the band would learn. Ronnie, who would usually act on gut instinct and say the hell with whoever disagreed with him, burned up the phone line with calls to Charlie Daniels, his confidant, concerned the band was asking for big trouble. Daniels told him to keep it in the act, that it would do more harm than good to remove it, and that the issue would recede when critics came to size up Skynyrd as a nonpolitical bunch with a regional angle that cut to the heart of the South’s identity—not as racists but good, decent folks keeping the faith with its traditions sullied by civil war and opprobrium for its mistakes. Skynyrd’s songs were, after all, about just those elemental themes.

Or most of them. With “Sweet Home Alabama” they would inject a new element, taking them into deeper water. Indeed, the first manifestation of the flag was the jacket art for the single release of the song, featuring an image of a young woman’s beckoning lips, onto which were stuck a color image of the Confederate flag. This put the race angle in blatantly sexualized terms, always the most incendiary of all in matters of race, not long separated from the days of Emmett Till when a black man could be lynched for merely looking at a white woman. As squeamish about it as the band was, when the lights went up on their shows, audiences went absolutely crazy. There would be deafening shouts of yee-haw! and others cries that sounded like they emanated from barnyard animals. On the opening guitar bars, feet stomped, hands clapped, and the building shook. When Ronnie sang, “Big wheels keep on turning,” a mass sing-along would erupt. Emotions would keep rising until the great climax of “Free Bird” left everyone limp.

The phenomenon was unlike anything they had seen, and it helped manufacture an institutional engraving for the song. As Ed King says, “I’m sure Dickey Betts disagrees, but ‘Sweet Home Alabama’ is the Southern anthem.” But, as it happened, part and parcel of this was that most southerners and those who felt like southerners listening to Skynyrd took the lyrics of the song as a cue to release some not-so-courtly feelings. The easiest thing for the band to explain was the fight they had picked with Neil Young, who for his part refused to take the bait and indulge in a cheesy “feud.” He expressed no ill will and said he greatly admired Skynyrd, which he proved in future years when he said the lyrics of his that Ronnie had objected to were “condescending and accusatory” and “not fully thought out.” Indeed, Young had some repenting to do; in 1972 the soundtrack of his pseudodocumentary Journey Through the Past was released with cover art depicting hooded horsemen carrying cruciform staves and an inset photo of Young glaring at a Confederate flag. If Van Zant wasn’t pissed off by that, he may as well have walked away from his birthright.

Al Kooper helpfully confirmed that Young “loved” the Skynyrd song. And proving that there never was a schism between them, Van Zant and Young began discussing collaborating on future songs. Ronnie pointedly wore T-shirts on stage screened with Young’s face. Neil would wear a Skynyrd/Jack Daniel’s T-shirt. After Ronnie’s death, Neil Young would perform a cover version of the very song that had taken him to task.

Not so easily dispensed with was the reaction to those confusing lyrics about Wallace and Watergate. With people in his circle beginning to wonder if he had produced a racist band, Al Kooper suddenly was not so sure about what the song said. “Hey, you have to be more careful when you write a song now,” was his revised opinion. Skynyrd might have wanted to say to him, “Hey, Al, nice of you tell us that now.” Pissed off that they even had to address the issue, they acted as if anyone who asked was an idiot. Ronnie, far from what he told Artimus Pyle later, called it a “joke song” and “a party tune” that he never thought would ever be released as a single, and that when it was, it “hit Top 10 and we’ve been paying for it ever since,” though they also had been paid for it ever since, quite well. “We’re not into politics,” he said. “We don’t have no education, and Wallace don’t know anything about rock n’ roll.”

Ed King, however, doesn’t toe the company line these days. Contrary to what Van Zant may have told Pyle, King says, “Ronnie was a big fan of George Wallace. He totally supported him. We all did. We respected the way Wallace stood up for the South. Anybody who tells you differently is lying.”

What Van Zant was trying to do was clear the biggest hurdle for any Southern Man: separating the concept of “standing up for the South” from the chaff of innate racism. It would seem impossible that he could have worked Wallace into these lyrics as he did without realizing that the man was a breathing synonym for intolerance. Wallace himself would need to go to great lengths later in his life to remove the stigma, saying in 1998, “I was wrong. Those days are over, and they ought to be over.” The need for Van Zant to walk the racial tightrope was unavoidable, especially after his own record company had put him up there on that high wire. If the crackers embraced Skynyrd, it was still incumbent on him—not on the suits at MCA but the band’s leader—to assure the record-buying public that nothing racist was meant by “Sweet Home Alabama.” And, no matter his feelings about “the Gov’nor,” he did so, with great contrition.

“Of course I don’t agree with everything Wallace says,” he said. “I don’t like what he says about colored people”—yet the fact that he used a pejorative term for African Americans while insisting nothing had been pejorative in the song only underscored the quandary of acting southern without malice carved out of southern conditioning.

He went on, “We’re southern rebels, but more than that, we know the difference between right and wrong…. My father supports Wallace but that doesn’t mean I have to…. I’ve heard him talk and wanted to ask him about his views on blacks and why he has such poor education and such a low school rate there, such a low housing rate,” meaning for African Americans.

His best case for proving that the song was actually a sly rebuke of Wallace lay in those three repetitive syllables in the verse that he explained were the key to understanding the entire song. “The lyrics,” he said, “were misunderstood. The general public didn’t notice the words ‘Boo Boo Boo!’ after that particular line, and the media picked up only on the reference to the people loving the governor.”

Not everyone bought it. As was the case with the rest of the lyrics, the “Boo! Boo! Boo!” refrain could be construed any way the imagination wanted. If he had been serious about debunking Wallace, why not say it, in words, something like, say, “In Birmingham they love the Gov’nor / Well, that ain’t something they should do.” Why go with a guttural ballpark response to an umpire’s bad call? Still, it provided plausible deniability, though that was not really needed; in fact, the murky connection with Wallace seemed only to add another whiff of outlaw chic. Skynyrd might have been pissed about the brouhaha, but they could live quite nicely with having a hit. And if anyone needed a period to put on the end of the sentence, Leon Wilkeson offered it. “I support Wallace about as much as your average American supported Hitler,” the inscrutable bassist said.

Wily bush dog that he was, Van Zant likely was apolitical, it not being worth the aggravation of lecturing people who just wanted to hear him sing, not talk. The only endorsement for a candidate he ever made was still on the horizon, support he would offer when another son of the South ran for president—a Democrat, of all things, a clear case of regional loyalty being political enough for him. He did know that he had a tightrope to walk, playing to type in his writing and stage persona while avoiding any taint of too-literal Confederate status; it was already a heavy enough lift for MCA’s radio liaisons to get Skynyrd played on FM stations in the North. And in fact, Ronnie was a different sort of Confederate soldier, as was Wallace, who despite his segregationist stance never got on board with standard right-wing doggerel about the underclass being, in the contemporary vernacular, “takers”; indeed, by then Wallace had won a certain fealty among Alabama’s black underclass, having raised taxes on the rich to sink money into the ghettos.

That was the Wallace with whom Van Zant related. “To me,” Ed King says, “Ronnie was a proud, working-class southern man, and George Wallace represented proud, working-class southern people. To Ronnie, Wallace was not just a man who wouldn’t let blacks into a college, he was a man who spoke for poor, uneducated people who didn’t have a voice. It’s right there in [‘Sweet Home Alabama’].” Still, it was never easy to split hairs when it came to Wallace. The “Gov’nor” so loved the song that when Skynyrd and the Charlie Daniels Band played a gig in Tuscaloosa, Wallace appeared on stage to present Skynyrd with plaques making them honorary lieutenant colonels in the Alabama State Militia—another symbol of racial grievance, since the militia had imposed martial law during the civil rights marches. Rather than steering clear of the “honor,” they eagerly jumped at the chance to be deputized. Indeed, agreeing with King, Charlie Daniels recalls that Van Zant “had great respect for George Wallace. Ronnie was a southerner, man [and when] they got plaques from the governor … they were just tickled to death about it.”

Yet here too Ronnie had to backtrack, calling the interlude a “bullshit gimmick thing,” neglecting to say that the band kept that hardware and their “commissions” in the militia. And decades later, when the song was made into the state motto, no one in the band calling itself Lynyrd Skynyrd threw that fish back either. Al Kooper tells of the time when, during the recording of pronounced, he brought to the studio a guitar that had been given to him by Jimi Hendrix. Someone he identifies only as “one of the Skynyrd boys” began fooling with it, saying, “Hey, Al, this guitar plays nice.” From across the room, Ronnie said, “That guitar used to belong to Jim Hendrix,” whereupon the guy, Kooper says, “let it fall out of his hands onto the couch. ‘OOOO… I just got some nigger on me!’ he screamed irreverently.”

“You better pick that guitar up,” Ronnie said, “and see if you can get some more of that nigger on ya.”

Naturally, such palaver was meant in jest, but it did show how easy it was for men of the South to fall into racially offensive dialogue odious to northerners and progressive southerners. One Yankee journalist, Jaan Uhelszki, who was sent to write a piece about Skynyrd for Creem, claimed the experience made her feel like she needed to be deloused. After meeting Rossington, she said she expected him to tell her “some juicy tales of nigger skinnings.” Mark Kemp, then a southern music journalist and later an editor at Rolling Stone and vice president at MTV, wrote in his 2004 book Dixie Lullaby of visiting Ed King and asking if anyone in the band had ever uttered racist thoughts. “When King’s wife, who was sitting at the table with us, chimed in, saying, ‘Oh, please, I remember Gary making a comment just a few years ago,’ King immediately interrupted her.” Choosing his words carefully, King then told Kemp, “I don’t have any personal experience with that. But I can tell you this: unlike the Allman Brothers, we never had any black people hanging around Lynyrd Skynyrd at all. At all. I mean, none at all.”

Yet, as if King himself had been bitten by the routine, quotidian expression of racism during his time with the band, he too betrayed some rather acrid opinions during the highly charged debate surrounding the Trayvon Martin killing in 2013. King wrote on his Facebook page that young black men were “lazy,” “thugs,” “killers,” and “thieves,” and that blacks in America have “had their reparations.” Kemp, who had believed King was the “enlightened” one in Skynyrd, took that label back.

“I thought he had more insight than other right-wing rockers. I was wrong…. Who the hell does this ex-southern rocker think he is to moralize so generically and condescendingly about ‘blacks’ he doesn’t even know?” (King later scrubbed the offensive remarks from his page.)

As much as Ronnie craved black recognition for Skynyrd, a few bluesy numbers did little to ameliorate centuries of cultural and racial conditioning.

While MCA had gotten down with the flag and was feasting on “redneck chic,” fashioning the band’s name in promotional materials and record jackets out of pieces of the Confederate flag, Ronnie began to feel the heat over it. Asked to explain what the flag meant to the act, he did his damndest to deflect the issue by folding it into his general beef about the “establishment”—the “gimmick”-hungry record company. “It was useful at first,” he allowed, “but by now it’s embarrassing.” Years later, Rolling Stone’s John Swenson bought into this construct that by flying the flag Skynyrd was actually making their own antiestablishment stand, the Old Confederacy being among that establishment. The flag, he wrote, had “some kind of complex relationship to the Confederacy, but it’s not about states’ rights or slavery; it’s something very personal. It’s closer to the whole idea of the Declaration of Independence. This was their version of it, being a rebel.”

It was a tortuous rationale, assuming a whole lot, but it did make some sense given the Skynyrd inferiority complex that would never end; as high as they got, they always saw themselves as mutts—dirty dogs—never accepted as anything more by the cultured rock Brahmins and thus never under any obligation to act like anything else. It was a self-serving prophesy and shield, giving them license to act like dogs. If the problem areas of the flag and “Sweet Home Alabama” were thorny, Skynyrd might deflect criticism but embrace the notoriety. In fact, rather than merely let the flag be an avatar, they went even further. Soon their sound equipment was painted battleship gray, a “Confederate” hue that blended in with the backdrop of the flag. Ronnie even strode onto the stage one night clad in a Confederate officer’s coat and hat—though he later laughed it off as a “showbiz stunt,” his way of sending up the whole kerfuffle about the flag.

With so much at stake, all they could do was follow along with it and hope that lame clarifications about the “gimmicks” would keep the fallout off their backs. However, as time went on they almost became prisoner to that flag, even consumed at times by it. The first time Skynyrd took their show across the pond to Europe—a two-month trek beginning in mid-November 1974 with dates in Glasgow and Edinburgh, two weeks in England, three days in Germany, one day each in Belgium and France, and the finale at the Rainbow Theatre in London on December 12—the flag came too, though Europeans had not the slightest notion of the mortal insult it was to African Americans. As Ronnie reported, patrons such as those the band played for at venues like Britain’s Saint George’s Hall, Theatre Royal, the Kursaal, Theater An Der Brienne Strasse, Jahrhunderthalle, and Ancienne Belgique “really like all that [Confederate] stuff because they think it’s macho American”—which of course it was in a good part of America as well.

On one night during the well-attended and well-received tour, Ronnie happened to drop the flag onto the floor; he freaked out, as if he had committed a great sin against the motherland. Reaching for the phone, he called Charlie Daniels back home. The rotund fiddler, who himself had taken to wearing jumpsuits at his concerts covered with the Stars and Bars, recalled that the band had gone as far as to take the flag out to an alley and burn it, in accordance with antebellum protocol for flag desecration.

“Do you think it would be all right if we went on without the flag?” Ronnie asked him. “Certainly,” Daniels replied.

Ronnie sighed in relief. The symbol he insisted was a gimmick and an embarrassment had not been sullied on foreign soil after all. The honor of the South lived on.

The one-story wood-frame house that Lacy Van Zant built for his brood at 1285 Mull Street in “Shantytown,” the hardscrabble neighborhood on the west side of Jacksonville, stands pretty much as it did when Ronnie Van Zant was young. CAMERON SPIRITAS

Here, at Robert E. Lee High School, which still stands stately on South McDuff Avenue, the Shantytown boys ran afoul of crusty gym coach Leonard Skinner for wearing their hair too long, which earned them suspensions and inspired a ready-made name for their band. CAMERON SPIRITAS

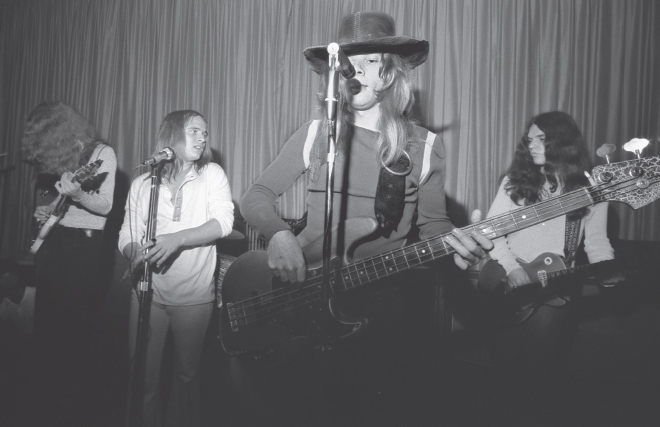

In perhaps the first-known photo of Lynyrd Skynyrd, the bandmates play onstage at Atlanta’s dingy Funochio’s club on July 21, 1972, with bass man Leon Wilkeson singing lead, while Ronnie Van Zant looks on. Gary Rossington strikes a chord while Allen Collins, his face hidden by hair, focuses on his own guitar. CARTER TOMASSI

Few would know that a slice of rock history was made in this drab warehouse at 2517 Edison Avenue, which in the early 1970s housed the Little Brown Jug, where Ronnie was inspired to write “Gimme Three Steps,” the semitrue tale of a flirtation gone very wrong. CAMERON SPIRITAS

Copping an Allman Brothers’ pose, Skynyrd lines up on a Macon, Georgia, street and shows some attitude for the cover of (pronounced ’lĕh-’nérd ’skin-’nérd), which would eventually go double platinum. From left to right are Leon Wilkeson, Billy Powell, Ronnie Van Zant, Gary Rossington, Bob Burns, Allen Collins, and Ed King. GETTY IMAGES

In this shot from May 6, 1973, taken during sessions for Skynyrd’s debut album at Studio One in Doraville, Georgia, Al Kooper, in the glasses, works the control board as Ronnie and Gary try to lend a hand and engineer “Tub” Langford stands by. GETTY IMAGES

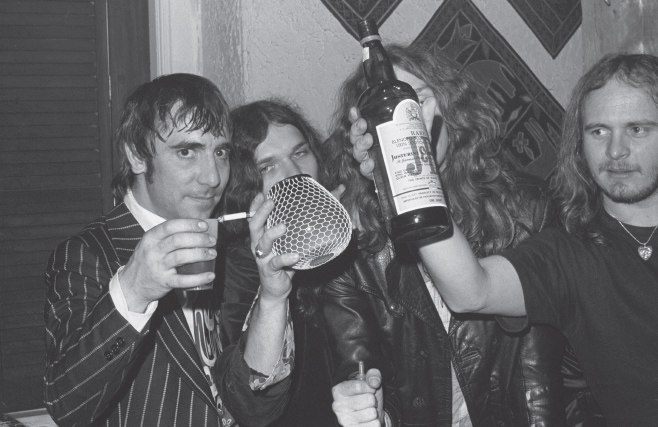

During Skynyrd’s 1973 tour with the Who, trying to keep up with the manic-eyed Keith Moon (left) Ronnie hoists a J&B in front of Allen’s face while Gary appears to look for something to ingest from a candle bowl. GETTY IMAGES

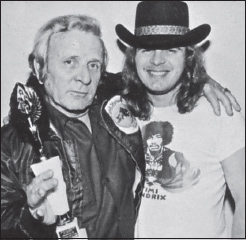

Lacy Van Zant, who dubbed himself the “father of Southern rock,” poses here with son Ronnie in 1975. DAVID M. HABBEN

If Ronnie was apt to take a swing at all the others in the band at any given moment, he had nothing but admiration and even some envy for the clean and sober guitar virtuoso Steve Gaines, who became Skynyrd’s newest member in 1976. AP

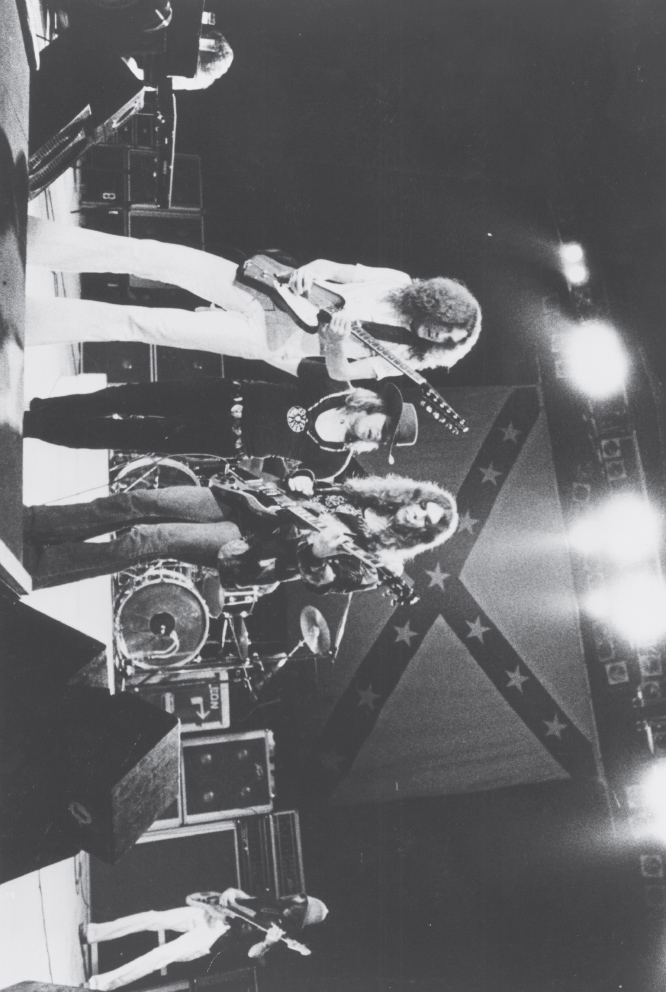

The essence of Skynyrd in a single image: Ronnie Van Zant, front and center, flanked by the guitar firepower of Allen Collins and Gary Rossington, the thunder of Leon Wilkeson’s bass rolling in from stage right and Billy Powell’s funky piano swirls from stage left—and a giant Confederate flag hanging over Artimus Pyle’s booming drums. GETTY IMAGES

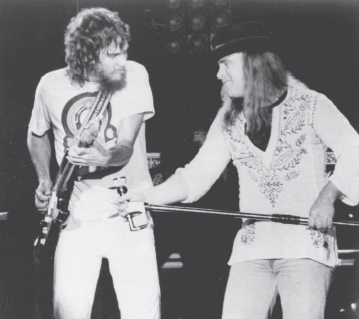

Ronnie and Gary rock out under blue skies that are so blue, not only in Alabama, but in Oakland, California, where this concert occurred. RALPH HULETT

October 20, 1977: Southern rock died in a swamp in Gillsburg, Mississippi, with the twisted wreckage of Skynyrd’s rickety Convair CV-300 strewn between the trees that tore it apart, killing Ronnie Van Zant, Steve Gaines, Cassie Gaines, Dean Kilpatrick, and its two inept pilots. Miraculously, the other nineteen passengers on board survived. AP

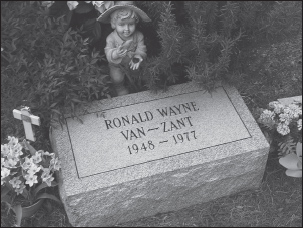

A simple headstone in Jacksonville’s Riverside Memorial Park marks the grave of Skynyrd’s front man and of the southern rock movement. The original grave site was vandalized in 2000, necessitating that Ronnie’s remains be moved to a concrete vault deep under the stone. DAVID M. HABBEN

The “Father of Southern Rock,” as truck driver Lacy Van Zant dubbed himself, was laid to rest in 2004 alongside his wife, Marion Hicks “Sis” Van Zant, in Riverside Memorial Park, the same grounds where Ronnie Van Zant is buried. DAVID M. HABBEN

March 13, 2006: Oft-denied, Skynyrd was finally elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, giving the band a chance to bask in pride—though the body language of everyone but Billy Powell betrays the hurt feelings that still existed for Gary Rossington, Artimus Pyle, Ed King, and Bob Burns. AP

The Freebird Live Cafe on Jacksonville Beach—owned by Judy Jenness, Ronnie’s widow and the executor of his estate—is the sort of place where the fledgling Lynyrd Skynyrd might once have honed their sound. CAMERON SPIRITAS

One of the many tributes to Jacksonville’s most famous native son is Ronnie Van Zant Memorial Park, an eighty-five-acre stretch of greenery and crystal blue lakes in the Penney Farms area—the sort of spot where Ronnie might get away to fish, though he likely would have disobeyed the NO CURSING signs. CAMERON SPIRITAS