THEIR only weapons were a thin willowy stick, a pair of scissors, a pocket full of nails and a revolver. Yet they were the advance guard of the 16 000 Australian and British troops who assembled on the dark face of the desert on the night of January 20th, 1941, ready to attack Tobruk before dawn. On the steady nerves and fingers of these men with strange weapons, the waiting infantry relied to clear the maze of booby-traps, which screened the Italian defences.

They were thirty-three members of the 2/1st Field Company, led by Lieutenant S. B. Cann. Several hours before moonrise they moved out into no-man’s-land to the accompaniment of jibes from infantry, who little realized how important those thin willowy sticks were. A stinging wind swept across the desert and the sappers were thankful for their army-issue jerkins and long woollen underwear, and for ‘rum-primed’ water-bottles, which were some compensation for the greatcoats they had left behind. To lessen risk of detection they wore woollen Balaclavas instead of tin hats and their shiny leather jerkins were turned inside out.

For more than three hours the sappers felt their way round among the booby-traps working as fast as half-numb fingers and the all-too-close enemy patrols would let them. If they were not to be discovered, they had to finish delousing the necessary 2000-yard gap in the belt of traps in front of Posts 55 and 57 before the moon rose at 1.15 a.m. But, as it climbed over the horizon, some sappers were still lying on their stomachs, feeling for booby-traps, while an Italian patrol passed only seventy yards away. It was over an hour before these sappers managed to crawl back undetected.

In the concentration area, three miles south of the perimeter, the booby-trap parties finally rejoined the rest of the 2/1st Field Company, and the 2/3rd Battalion. At 2.30 a.m. the troops had a meal, brought up from unit kitchens in hot boxes, and got ready to move. The Navy’s preliminary bombardment had ended at midnight, but soon the R.A.F. was pounding the inner Tobruk defences. To the distant music of their own bombs the troops marched to the start-line 1000 yards south of Posts 55 and 57. They were glad to be on the move at last, for the strain of waiting without talking or smoking was worse than going in to attack. They were as eager for the first bark of the barrage as a sprinter for the starter’s gun. Company by company they took up their positions on the taped start-line. One last check on equipment and orders and they were ready.

About 5.30 there was a lull in the bombing and stillness once more settled on the desert. Back behind the assembly area at a British 6-inch howitzer position, I watched the gunners gulp their last mouthfuls of bully-beef stew and tea as they stood by their guns. The ‘hows’ were ready, loaded and laid. There was no sound except the voice of a signaller speaking from a shallow dug-out behind the gun-pits to an officer at the observation post – a low mound in the desert a mile or more from the perimeter. At the entrance to the dug-out the troop commander was peering at his luminous watch, set like all other watches for the battle by the B.B.C. time signal. Megaphone in hand, he waited to give the order. The last few silent minutes dragged by . . . 5.38, . . . 5.39, . . . 5.40 – ‘Fire!’

His voice was lost in the roar of the four howitzers as they spoke together. Breeches flew open, were loaded and slammed shut. The guns settled down to a slow, rhythmic pounding almost as regular as the beat of a pump. Soon they stood in a dust-cloud of their own making.

The leading troops were already on the move. From the sea to the north of them, from the land to the south, east and west of them, came the thunder of the heaviest bombardment the Middle East had known. Out to sea stood more than twenty warships, including three 15-inch battleships; firing from the desert were 166 guns. Sixty of them put down a box barrage on and around the five posts that the 2/3rd were to attack first. Meantime the other hundred guns concentrated on three tasks: neutralizing the posts nearest to 55 and 57; silencing the most dangerous batteries beyond these posts; and shelling the Bardia road and western sectors to provide a diversion.

The desert across which the troops advanced was so flat that they could see the flash of their own guns firing behind them and of their own shells bursting in front. From their new positions the gunners had not fired even ranging rounds, but the infantry soon knew that the artillery was right on its targets. As the troops moved towards the wire very little enemy fire met them and much of what there was went well over their heads. But as the 2/3rd got near the anti-tank ditch one chance salvo landed in the middle of Major J. N. Abbot’s ‘C’ Company, killing or wounding an officer and twenty men.

With the infantry went some engineers with Bangalore torpedoes. Other sappers followed behind to clear the minefield, which lay between the belt of deloused booby-traps and the anti-tank ditch. The minefield did not check the infantry. The mines were not set to explode under a man’s weight and the Diggers picked their way safely through. At 5.55 a.m. they reached the anti-tank ditch and took cover there for ten minutes while our gunners concentrated their fury on Posts 55 and 57.

As the troops lay there more than a ton of high explosive burst on and around each of these posts every minute. This was the climax of the 25-minute bombardment in which 5000 shells had plastered an area a few hundred yards square. They had left many scars but few craters in the stony ground which made the shell splinters spread farther, and magnified the blast. For the Australians in the ditch the noise was deafening, but in the concrete dug-outs, where the Italians lay, the detonations reverberated like a succession of thunder-claps, leaving the garrisons dazed.

During all this the C.O. of the 2/3rd (Lieutenant-Colonel V. T. England) was in the ditch with the attacking companies, but, when Brigadier ‘Tubby’ Allen joined them, England said, ‘Isn’t this a bit far forward for Brigade H.Q.?’ ‘I came up to dodge the shelling,’ replied the Brigadier.

At 6.05 a.m. the barrage lifted from the two forward posts, and engineers raced to the wire – which was anything from twenty to fifty yards from the ditch – dragging their long Bangalore torpedoes. Some were hit. A shell landed among a pioneer detachment of the 2/3rd wounding all but one man, Private R. A. McBain. Undaunted, McBain dragged a Bangalore to the wire alone and scrambled back into the anti-tank ditch as it went off. Meantime at four other points along a 400-yard section of the wire other engineers had done the same, but, through some mischance, not all the torpedoes exploded. Knowing that the wire must be blown at all costs, sappers dashed forward again with new torpedoes and by 6.15 five clear gaps were open for the infantry. But it was still a race against time. In the half-hour of darkness that remained the two leading companies had to take three forward and two supporting posts, covering a front of over a mile.

Through gaps to the right went Abbot’s depleted company, to capture Posts 57, 58 and 59. The platoon that attacked 57 was on top of the post before the Italians had recovered from the barrage, but darkness and the smoke and dust raised by the shelling made it hard to find the other posts. In the confusion Sergeant L. L. Stone’s platoon was about to open fire on some shadowy figures, when one of them dashed forward using language which was unmistakably Australian. Lieutenant D. E. Williams’s platoon had lost its way. Momentarily disregarding the enemy fire, Stone took time off to apologize. ‘Don’t worry,’ said Williams, ‘I put it down to excessive zeal.’ And he led his men off to take Post 56.

On the other flank ‘D’ Company, commanded by Captain R. W. F. McDonald, had a hard fight, which was won only just in time. The platoon that went for Post 54 became lost in the darkness and somewhat disorganized under heavy fire. The situation was saved by the prompt action of McDonald who rallied the men and led them in to take the post.

Meantime it was touch-and-go whether Lieutenant J. E. Macdonald’s platoon took Post 55. There the enemy had six machine-guns and a light field piece, and even though the Australians attacked from the rear, they came under heavy fire. As they rushed the post all but Macdonald, a sergeant and one man crashed through the flimsy camouflage covering the anti-tank ditch that encircled the post. Macdonald was wounded, but he continued on, pitching hand grenades towards the Italian machine-gun pits. The man beside him was killed and he himself was wounded again, yet he kept the post quiet while his sergeant rallied the platoon for a final attack. Only two of the garrison of twenty-two were captured unwounded.

By 6.40 the two attacking companies had taken the five posts, which were their initial objective, and ‘B’ Company of the 2/3rd was holding the edge of the escarpment a thousand yards north of 54 and 56, to check any counter-attack from that quarter. The bridgehead was established a mile wide and a mile deep.

By this time too the engineers had cleared the minefield for several hundred yards on either side of the gap and had dug-in the sides of the anti-tank ditch to make crossings for the ‘I’ tanks, carriers and vehicles which were already streaming towards the perimeter. In the grey dawn light, as the first column of prisoners moved back, they passed the leading British ‘I’ tanks and the 2/1st Battalion on their way in to exploit the advantage already won. The first critical phase was over. The danger that the attacking companies might not clear a bridgehead before daylight, and that the supporting battalions might be caught in the open by an alert enemy during their approach march, had been averted.

Herring’s gunners had done their job well. The Italians had been slow to realize that anything special was afoot and by the time they did bring their guns into action many of ours had been switched from the barrage supporting the break-through to concentrations on Italian battery positions. Many of the enemy guns that had been intended to cover the area of the break-through had been neutralized; but others, including coast defence and ack-ack guns, were now swung round to shell the area across which the British and Australian troops were advancing northward. The 2/1st Battalion (commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel K. W. Eather) had some anxious moments getting through the gap. Before they reached the wire coast defence guns were landing big stuff behind them, while ahead salvoes from enemy field guns were coming down along the anti-tank ditch. Luckily the Australians managed to hurry through during a brief lull.

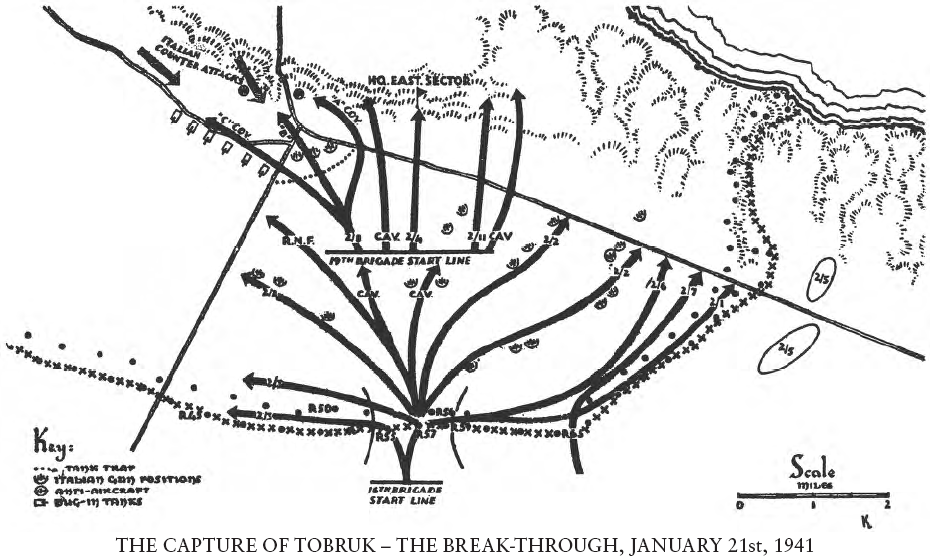

As soon as the first six tanks reached the gap, three of them swung right to lead the 2/1st in rolling up the perimeter posts to the east as far as the Bardia road. The other three turned left to help the 2/3rd do the same thing with the posts to the west, between the bridgehead and the El Adem road. Both were supported by artillery concentrations moving ahead of them and switching from post to post. As these two battalions started widening the gap, nine more tanks followed through in front of the 2/2nd Battalion. Its task – with the help of these tanks – was to deal with the batteries inside the perimeter on the northern flank of the 2/1st and 2/3rd Battalions.

This worked out almost exactly to plan, except that, after overrunning nine posts in the first two miles of their push westward, the 2/3rd were then held up by stubborn opposition from Posts 45 and 42, half a mile short of the El Adem road. Until then the going had been fairly easy. The general tactics were that tanks and infantry followed as closely as possible behind the barrage, and those posts which were not silenced by shelling were kept quiet by tanks, while infantry moved in with bayonet and grenade to enforce surrender. What fight was left in the Italians after the bombardment was in most cases subdued by the sight of the tanks and bayonets. Some even surrendered when they saw the garrison of the post ahead of them march out with white flags.

By the time the leading companies reached the area of Post 45, however, their three tanks were all out of action through mechanical trouble or minor damage and the infantry were pinned down on a forward slope, providing a tempting target for the enemy. The white patches which the troops had stitched on the backs of their haversacks so that they could distinguish each other in the dark were now all too clear to the enemy. His fire was not easy to silence. One disabled tank was too close to 45 to allow the artillery to shell this post heavily and the enemy guns beyond the road could not be easily located. Until fresh tanks were available further progress could be made only at unnecessary cost. It was 1.30 p.m. before they arrived and the battalion could move forward again, but the delay did not affect the action at large, for the 2/3rd had already cleared a wide enough gap on this flank.

Meantime by 9 a.m. the 2/1st Battalion had reached the Bardia road. Excellent co-operation between artillery, tanks and infantry had smothered all Italian resistance. As the enemy’s supporting gun positions were being simultaneously over-run by the 2/2nd Battalion and ‘I’ tanks, his infantry in the perimeter posts had little chance. Speed was the key to the attack’s success, but only first-class troops could have captured twenty Italian strongposts and kept up with the barrage, which moved four and a half miles in two hours. Without the tanks this pace could never have been maintained. The infantry, more impatient and less squeamish than they had been at Bardia, did not hesitate to pitch grenades into the concrete dug-outs if the Italians were slow in surrendering. Usually a grenade thrown into one end of the post brought the garrison streaming out the other. But when they were stubborn, the leading companies did not wait. They merely kept the enemy quiet, while they swept on to their next objective, leaving the supporting companies to do the mopping-up.

At one post, however, the tank leading the attacking platoon was disabled by a direct hit, which jammed the turret. The Italians maintained their fire, and the post was captured primarily through the gallantry of Private D. M. McGinty, who went forward alone, firing his Bren from the hip, and silenced the enemy machine-guns. One or two posts were left to be mopped up by the 2/6th Battalion, which was following along in support, and for a time the rear of the 2/1st came under fire from these. Luckily this fire was inaccurate and there was no serious hitch until the leading companies reached the Bardia road shortly before 9 a.m.

By this time the guns that had been supporting the 2/1st had been switched to help the 19th Brigade’s attack, and when Captain J. H. Hodge led his company across the road they came under heavy machine-gun fire. They took the four nearest posts but could make no impression on the next two, and for over an hour were pinned down in the anti-tank ditch north of the road. They were not extricated until 10.30 when a company of the 2/7th Battalion attacked the obstructive posts from the flank. (The 2/7th had entered the perimeter at Post 65, about half-way between the bridgehead and the Bardia road, as soon as the 2/1st and 2/6th had passed. It had now come up to relieve the 2/1st, and the 2/6th had moved farther west to relieve the 2/2nd.)

Well before this the 2/2nd Battalion had cleaned up the battery positions between the Bardia and El Adem roads immediately behind the sections of the perimeter over-run by the 2/1st and 2/3rd. These positions fanned out in three lines behind the bridgehead. Three companies of the 2/2nd, each supported by three ‘I’ tanks and twenty-four guns, had been detailed to attack these three lines of batteries.

It was a daring plan, for the companies were in effect deep patrols operating behind enemy lines, which were simultaneously being attacked by other battalions. This plan had been tried at Bardia, but had not been an unqualified success, primarily because a number of enemy guns had not been silenced by our artillery or else not located at all until the infantry came under their point-blank fire. If it were going to succeed at Tobruk, our shelling of the enemy batteries had to be accurate and severe and the infantry had to follow in behind the barrage so closely that the enemy could be overwhelmed before he brought his guns into action. So that his battalion would know its role perfectly, the C.O. of the 2/2nd, Lieutenant-Colonel F. O. Chilton, before the battle had the detailed plan explained to each man on a sand table model.

The result was a sweeping success. Advancing behind a 44-gun barrage the two companies on the right captured ten battery positions, each containing either four or six guns, and advanced more than two and a half miles in an hour and a half. The company on the left was equally successful. In each case, however, long before the infantry gained its first objective the tanks were lost in the dust and half-light of the early morning, but they roamed well ahead shooting up everything they saw.

The Italian gun positions had few infantry to protect them and most of their gunners were still too dazed by our shelling to offer much resistance to the Diggers, who appeared unexpectedly out of the dust-cloud the shells had raised. Some of the guns – and particularly an ack-ack battery firing shrapnel over open sights – were troublesome, and in dealing with these the infantry made up for the lack of tanks, by fire from mortars mounted on carriers.1 Throughout the attack Chilton’s greatest problem was to keep contact with his widely-scattered companies. He was able to do this primarily because the capture of Bardia had given the 6th Division a much-needed haul of motor-cycles for its dispatch riders.

While the 16th Brigade was rolling up the perimeter posts and their supporting field guns on either flank of the bridgehead, the area immediately north of it was cleared by a mixed force of carriers of the 6th Divisional Cavalry, machine-gunners of the Northumberland Fusiliers and anti-tank guns of the 3rd Royal Horse Artillery. By 8 a.m. this force had over-run several Italian battery positions and penetrated two and a quarter miles inside the perimeter. There it reached the line that the 19th Brigade had chosen as the start of its deep northward thrust – the second phase of the attack.

Before 8.30 the transport of the attacking battalions was moving inside the perimeter. I nosed my utility truck into one column heading for Post 65 where the 2/7th Battalion had gone through about two miles east of the bridgehead. Near the perimeter a military policeman rattled past on a motor-bike shouting to drivers, ‘Keep moving – don’t bunch up and don’t get off the marked track. There’s still mines about.’ The danger from bunching was slight because the Italians had not yet found this gap, and in addition our shelling made their fire ragged. A few strays landed about five hundred yards away and threw up tall, thin columns of dust, which rose in the still morning air like brown poplars.

In front of Post 65 sappers had cleared a track through the minefield and thrown a narrow wooden bridge over the deep anti-tank ditch. The bridge was as busy as Pitt Street, Sydney, at 5 p.m. The vehicles moved forward – tailboard to radiator – enveloped in dust. Military police shouted themselves hoarse as they urged the drivers on. Beside the ditch were chalked signboards – KEEP MOVING: NO PARKING. Other signs – CAUTION MINES – were hung on the flimsy wire fence, which marked off the enemy minefields. As cars, ambulances and trucks moved by the Australian newsreel man, Damien Parer,2 was filming them. The sight of the trucks of the photographic and broadcasting units parked together prompted one policeman to comment to another, ‘Blimey Bert, propaganda goes ter war!’

Inside the perimeter I turned west towards the sector where the 2/3rd had broken through, and came to a post that was still resisting. The 2/1st Battalion had over-run this area, but when the post held out they went on, leaving the 2/6th to mop it up. Machine-gun fire and hand grenades had failed to shift the Italians from their underground shelter. As I got there the Diggers were ‘rabbiting’. They lit some crude oil at one end of the trench and three Italian officers and thirty-four men bobbed out the other.

Farther on outside the wire well over a thousand prisoners, shepherded by four Diggers, shuffled through the dust. Bardia had shown the troops that large escorts were not needed. One brigade there had finally instructed its battalions – ‘Prisoners will not be sent back in lots of less than one thousand.’

At Post 57 the 16th Brigade had its battle headquarters, but the first thing I saw was four engineers heating Italian coffee on a captured primus and breakfasting on Italian tinned stew. This was typical of the general air of normality – the battle might have been fifty miles away. A postal orderly was dealing out mail that had come up on a ration truck. In a machine-gun pit an officer with a map on his knees was talking on the phone. Up the steps from a concrete dug-out came two Diggers, their arms filled with Italian uniforms, dixies and other junk. They were turning the dug-out into the Brigade Signals Office. Near the entrance Brigadier Allen was talking to two liaison officers. They finished pencilling instructions in their notebooks and hurried off to rejoin their battalions.

By 8.30 the stage was set for the second act. In the critical hour and three-quarters since daylight, eight infantry battalions, more than fifty tanks and carriers and a dozen anti-tank guns had moved in through one narrow bridgehead. The attack had gained such momentum that the Italians would have little hope of stopping it unless they could organise rapidly a strong counter-attack.

Brigadier Robertson, however, had planned his advance to defeat just such a move. To secure a deep penetration he drew up his battalions in arrowhead formation, with the flanks covered by the captured tanks, and carriers of the 6th Divisional Cavalry. The 2/4th, in the centre, was to head due north and capture the eastern sector H.Q., located in a wadi about a mile north of the Bardia road, while the 2/11th cleared wadis on the right and linked up with the 2/6th Battalion along the Bardia road. Simultaneously the 2/8th was to capture the strongly defended junction of the El Adem crossroads.

With forty 25-pounders shelling this road junction and another forty putting down a creeping barrage in front of the tanks and infantry, the 19th Brigade attack began at 8.40 a.m. The barrage lifted at a hundred yards a minute, but the infantry maintained parade ground pace to keep up with it. The troops had been so impressed with the need for speed, that at times the 2/4th almost ran into the barrage and the leading companies of the 2/8th forged ahead of the tanks.

For the first mile, from the start-line to the Bardia road, the artillery blotted out all opposition in the path of the 2/4th, but then they came under heavy machine-gun fire from positions near the road junction. However, Vickers guns on the supporting carriers soon silenced this fire and the 2/4th advanced two and a half miles and captured the sector H.Q. in less than an hour.

On its right flank Lieutenant-Colonel T. S. Louch’s 2/11th kept pace. On the left the 2/8th struck little opposition from the crossroads area until the barrage lifted from there to the gun positions farther north. Then the 2/8th came under close range machine-gun and artillery fire from what was virtually an inner perimeter, circling the road junction and running west towards Fort Pilastrino.

The Italians had not completed these defences but they were quite formidable. Behind mines, barbed wires and stone walls, they had a number of machine-gun emplacements, some concreted, others protected by sandbags or rocks. On the ground in front of these were aerial bombs, explodable by trip-wires, and behind them were four 6-inch naval guns and an anti-aircraft battery. In addition there was a double line of tanks dug in as pillboxes – seven mediums in the angle between the two roads and another twenty-two medium and fifteen light tanks west of the El Adem road.

Fire from these defences was answered by the cavalry’s carriers and one tank – for, in spite of all the cavalry’s good work, only seven captured tanks survived the approach march and only one of these reached the road junction, all the others falling out with mechanical trouble. However, under cover of fire from the carriers and this one tank, the infantry got right to the Italian positions with comparatively few casualties. But, even so, dealing with the dug-in tanks was no easy task. Against those south-east of the road junction, the C.O. of the 2/8th (Lieutenant-Colonel J. W. Mitchell3) sent his ‘B’ Company commanded by Captain C. J. A. Coombes. Two other companies were sent round the flanks to envelop the position. Captain Don Campbell’s ‘C’ Company pushed across the El Adem road to tackle the line of tanks to the west, while ‘A’ Company, under Major H. H. McDonald, crossed the Bardia road east of the Italian position to strike at the guns north of the road junction.

The tactics of the different platoons in dealing with the dug-in tanks varied, but they had the common virtue of courage, blended with cheek. In some cases fire from anti-tank rifles4 penetrated the tank and dislodged the crew. If these tactics failed a couple of men worked forward close enough to put a burst from a Bren through any hole in the tank’s armour. As a final resort one or two men rushed the tank, climbed on top, opened the lid of the turret and dropped a hand grenade inside.

The hero of one of these attacks was Sergeant Jim Burgess. Dashing forward through heavy machine-gun fire, he reached a tank and climbed on top of it, grenade in hand, ready to drop it inside with the pin removed.5 But as he tried to open the turret lid he was severely hit by a machine-gun burst from another tank. As he toppled back, he struggled to put the pin back in the grenade so that it would not explode among his men, who were waiting in the lee of the tank. He succeeded, fell and died.

Gradually, by attacking the tanks from the flank so that they came under the fire of only one or two at a time, the 2/8th silenced every one. Their task was made difficult, however, by the stubbornness with which the Italian machine-gun posts held out. These were finally cleaned up with bayonet and grenade, but this took time, for in some posts the Italians lay low while the first infantry went through, and then fired on the following troops.

Meantime ‘A’ Company had had a stiff fight to take the guns north of the Bardia road. The Italians had the crest of the road covered by machine-guns and the infantry were pinned down south of it, until a squadron of carriers led by Lieutenant E. C. Hennessy came up, hull-down behind the raised bank of the road. As nearly all the carriers mounted both a Bren and a Vickers gun, they were able to blanket the enemy positions with fire while the infantry dashed forward.

Even so the infantry were not able to close on the Italians until Hennessy led his carriers round in a wide sweep to attack simultaneously from the enemy’s eastern flank. Hennessy managed to carry out this manoeuvre even though his carriers were a perfect target for the enemy artillery, while they were momentarily silhouetted against the skyline as they crossed the road. Then with a dozen Vickers and Brens covering them the infantry soon over-ran the Italian positions and captured seven hundred prisoners.

By midday the positions of the attacking battalions were as follows: on the Bardia road (from the perimeter inwards), the 2/7th, 2/6th, 2/11th, 2/4th and the 2/8th – the last-named being at the crossroads. On the general line of the El Adem road, 2/3rd, one company of the 2/2nd, two companies of the Northumberland Fusiliers. The 2/1st and the rest of the 2/2nd were marching across-country from the positions they had captured on the Bardia road to new positions on the El Adem road.

The 19th Brigade had now gained all its objectives and Brigadier Robertson had his headquarters near the El Adem crossroads. He was eager to push on as soon as the eighty-four guns allotted to him had moved up within range. The eastern half of the defences had crumbled, but most of the garrison was still holding out in the western sector, the commander of which, General Della Mura, had his reserve of tanks and infantry intact. During the morning he had tried to organize a counter-attack, but had been hindered by lack of information about the fighting in the eastern sector and by the R.A.F’s persistent bombing. At about one o’clock, however, R.A.F. Lysanders, which had been cruising round spotting for the guns and bombers all morning, sent urgent radio warnings that the Italians around Fort Pilastrino, four miles west-north-west of the El Adem crossroads, were massing for attack.

_____________

1 This was probably the first time carriers had been used for such a purpose, but in spite of their success, it was a year before this practice was adopted generally.

2 For the Bardia Battle Parer had been aboard one of the bombarding warships and he was now filming his first land action. He soon earned a name as one of the finest and gamest of war photographers.

3 Mitchell gained command of the 8th Battalion in the 1st A.I.F. at the age of twenty-six. He was the only commander of a 1st A.I.F. Battalion to receive command of the same battalion in the 2nd A.I.F.

4 The Boyes anti-tank rifle, which in these days was the infantier’s chief defence against tanks, is a heavy, long-barrelled rifle, firing a 1/2-inch armour-piercing shot. It was carried by one man and could penetrate a light tank and, at very close range, even an Italian medium.

5 The British hand-grenade or Mills bomb has a lever which is kept in place by a split pin. Even though the pin is removed the grenade will not explode until four or seven seconds (according to the setting of the fuse) after the lever has been released on leaving the thrower’s hand.