THIRTY-SIX hours after the last of the garrison withdrew inside the perimeter, the Germans began probing for weak spots preparatory to launching the concentrated attack that became known as the ‘Easter Battle’. Those thirty-six hours were invaluable. Throughout a hot, dusty day and night sappers laid a minefield around most of the perimeter, while infantry repaired barbed wire and shovelled sand out of the half-filled anti-tank ditch and concrete posts. Transport drivers toiled ceaselessly carrying ammunition, food and water to forward posts and artillery positions. Gunners dug-in their 25-pounders and camouflaged them as best they could. Signallers ran out several hundred miles of wire linking the scattered units. It was a period of hard work, hasty improvisation and urgent ‘scrounging’.

The infantry were perilously short of essential weapons, such as Bren guns and mortars. In time they made up for this by salvaging captured Italian weapons, but not many of these were ready for action when the first attacks came. Weak also in anti-tank artillery, the infantry recovered Italian field guns, which had been lying abandoned since the capture of Tobruk, and set them in position for anti-tank defence. Few of these had sights or instruments, but they were soon giving valuable support to the regular guns and became known as the ‘bush artillery’. The anti-tank defences were considerably strengthened by the last-minute arrival from Mechili on April 10th of the survivors from the 3rd Australian Anti-Tank Regiment and the 3rd R.H.A. They brought with them forty urgently needed guns but the garrison still had not enough to give adequate defence against Rommel’s great tank strength.

This was specially so in view of the inadequate minefields. Because of the scarcity of British mines, Italian ones had to be used, and there was no time to load them with booby-traps which could stop enemy sappers delousing them. This was done later, but in the first few days these mines were as easy for the Germans to delouse as they had been for the Australians. There was no reserve minefield, and work on the Blue Line had not begun when the first attacks were made. The signal position was still serious. With companies holding such vast fronts, telephone communication between forward posts and Company H.Q. was all-important, but the Italian phones, wire and switch-boards, which later gave Tobruk an excellent signals service, had not then been salvaged.

During April 9th and 10th, however, Rommel was no more ready for attack than Tobruk was for defence, and the garrison gained time to put at least the outer defences in order. It seems that Rommel had originally intended to go only as far as Bengazi and to consolidate there before launching his main attack on Cyrenaica; and that he pushed straight on across the desert merely because he found that the British armoured forces were so weak.

Consequently, by the time his vanguard got to Tobruk, he had over-reached himself and had to pause for a few days while the slower-moving elements caught up. Their advance, as we have seen, was delayed by a ‘dust blizzard’, under cover of which the last Australian units withdrew inside the perimeter on the night of April 9th–10th. About noon on the 10th the dust cleared and the 2/28th Battalion, then holding part of the western perimeter, saw enemy tanks and trucks coming down the road from Derna and across the desert to the south of it. Sappers promptly blew up the Derna road bridge just outside the perimeter and ‘bush artillery’ manned by infantry of the 2/28th struck the first blow for the garrison.

One of the gunners, Sergeant E. D. Rule, said later that when the battalion reached Tobruk it acquired eight Italian 75s and two 105s and dug them in about 500 yards behind the forward posts, near the Derna road, primarily for defence against tanks. A British artillery sergeant gave the carrier platoon a few gunnery lessons and by April 10th they were set for action.

‘On this morning,’ Rule said, ‘our Transport Officer was in command of the guns and, when the first enemy vehicles appeared, Battalion H.Q. said he could engage them. The guns had no sights but we got direction by squinting down the barrel, and range by trial and error. As it happened a British artillery colonel was there and he gave expert advice. Our gun drill wasn’t very good and our fire orders would have shocked the R.H.A., but we got the shells away. When the vehicles were about 500 yards out, the T.O. called, “All ready boys, let ’er go.” The first shell fell short. “Cock ’em up a bit, boys,” said the colonel. We did, and the second shot fell dead between the two leading vehicles. We kept on firing and they disappeared in a cloud of dust – and stayed out of range for the rest of the day.’

Soon afterwards, near the Derna road, another ‘bush artillery battery’ and some guns of the 51st Field Regiment had a more prolonged encounter, which ended in the destruction of two enemy armoured cars and seven vehicles. The Axis column withdrew, but not before its artillery had knocked out two guns and two Bren carriers.

Apart from spasmodic shelling and the occasional appearance of enemy vehicles in the distance, the garrison continued work on the defences undisturbed. But R.A.F. reconnaissance planes brought back unmistakable warning of the enemy’s intention. Early on the 10th pilots reported 700 enemy vehicles on the road between Gazala and Tobruk; by nightfall the leading vehicles were discovered only seven miles west of El Adem.

Before noon on the 11th – which was Good Friday – the Germans had by-passed Tobruk; four tanks and some lorried infantry had cut the Bardia road and a column of 300 vehicles was moving east between Tobruk and El Adem. Gott’s Support Group had to pull back towards the frontier. Tobruk was cut off.

On Good Friday afternoon the Axis forces staged a demonstration against Tobruk; it was half reconnaissance and half attack. They made their move against the southern sector of the defences, where Murray’s 20th Brigade was holding a 10½-mile front astride the El Adem road, with the 2/17th on the right, the 2/13th on the left and the 2/15th in reserve. The forward troops were still seriously short of weapons. The 2/17th, for instance, had only the normal establishment of one Bren gun per section and one anti-tank rifle per platoon. They had no anti-tank guns or 2-inch mortars forward and only one 3-inch mortar in the battalion. Captured weapons – so necessary to give them the fire-power to cover their 5-mile front – had not yet been issued.

In the middle of the afternoon the O.C. of the 2/17th’s left company (Major J. W. Balfe) saw enemy infantry, estimated at about a battalion, advancing out of the desert haze some 1500 yards from the perimeter. He called for artillery fire and, as shells began falling round the infantry, they went to ground. Enemy tanks appeared; the infantry rallied and advanced with them straight for Balfe’s company’s front. Our artillery intensified its fire and the infantry went down again, but the tanks continued on.

Balfe later gave me this account of the engagement that followed:

About seventy tanks came right up to the anti-tank ditch and opened fire on our forward posts. They advanced in three waves of about twenty and one of ten. Some of them were big German Mark IVs, mounting a 75 mm gun. Others were Italian M13s and there were a lot of Italian light tanks too. The ditch here wasn’t any real obstacle to them, the minefield had only been hastily rearmed, and we hadn’t one anti-tank gun forward. We fired on them with anti-tank rifles, Brens and rifles and they didn’t attempt to come through, but blazed away at us and then sheered off east towards the 2/13th’s front.

Before this about a battalion of infantry had advanced in close formation on that front as well. As these came on, an officer of the 1st R.H.A., who was directing his guns from a perimeter post, waited until the enemy was less than a mile from the wire. Then he ordered ‘twenty-five rounds gun-fire’ from his four 25-pounders. This sharp greeting stopped the infantry, but about twenty tanks (no doubt one of the waves of tanks which Balfe saw) that had been moving up behind them advanced through the barrage as far as the anti-tank ditch. Then they moved eastwards along the perimeter shelling the forward posts. Near the El Adem road they ran into fire from the Italian 47 mm anti-tank guns, manned by the 2/13th’s mortar platoon. One M13 was knocked out and several others hit. The rest sheered off and swung south. One Italian light tank was even disabled by intense small arms fire, and its crew was captured near the junction of the road and the perimeter.

As the tanks withdrew eleven cruisers of the 1st R.T.R. engaged them from inside the wire. When the last wave of ten tanks appeared the cruisers tackled them too. In thirty minutes of long-range sparring they knocked out one M13 and the artillery destroyed a German Mark IV. Three other Italian ‘lights’ were disposed of during the general skirmish, bringing the Axis losses to seven. Two British Tanks were lost, and since the garrison had only twenty-three cruisers it could ill afford to lose them.

After the Axis tank demonstration the infantry began to move forward once more. According to Balfe:

About 700 of them advanced almost shoulder to shoulder. The R.H.A. let them have it again, but, even though some of the shells fell right among them, they still came on. In later months our patrols in no-man’s-land found scores of German graves, marked by crosses dated April 11th. When the infantry were about 500 yards out we opened up, but in the posts that could reach them we had only two Brens, two anti-tank rifles and a couple of dozen ordinary rifles. The Jerries went to ground at first, but gradually moved forward in bounds under cover of their machine-guns. It was nearly dusk by this time and they managed to reach the anti-tank ditch. From there they mortared nearby posts heavily. We hadn’t any mortars with which to reply and our artillery couldn’t shell the ditch without risk of hitting our own posts.

About ten o’clock we got three mortars and with these kept their machine-guns quiet, while two platoons of the reserve company counter-attacked. But before they reached the ditch, the Germans had withdrawn. We sent two fighting patrols to follow them, but both were driven back by heavy machine-gun fire, which continued sporadically throughout the night.

Meantime there was even more significant activity on the 2/13th Battalion’s front. In the moonlight several enemy tanks came up to the anti-tank ditch, evidently looking for a shallow crossing. They could not find one, and withdrew. In the ditch shortly afterwards a 2/13th patrol disturbed what was evidently a party of pioneers, sent to blow the wire and make a tank crossing. The Germans cleared out, abandoning tools, explosives, Bangalore torpedoes, and a pack radio transmitter. Had this enemy party established a bridgehead, German tanks would no doubt have attacked at dawn. Anticipating this from the events of Good Friday and from R.A.F. reconnaissance, Lavarack during the night deployed the reserve tanks and infantry to meet any attack on the El Adem sector. None came but the enemy gave the garrison time for a useful dress-rehearsal.

Next morning – Saturday, April 12th – Balfe’s company found that the Germans who had withdrawn from the ditch the night before were dug in about 400 yards out on a 1200-yard front. Sniping from there, the enemy hindered the installation of seven anti-tank guns, which reached the perimeter posts about 9 a.m.

These guns arrived just in time, for the advanced screen of Germans was clearly covering preparations for a major attack. Dust-clouds rose from a slight hollow where the enemy was assembling tanks, guns and lorried infantry about 3000 yards out. Three Blenheims bombed one concentration of tanks and transport and the R.H.A. shelled others very heavily and no attack developed that day. After the gunners had landed 500 shells in ninety minutes among the group of sixty vehicles, half a dozen ambulances appeared and picked up the casualties. During the afternoon, in response to an urgent request from Lavarack, half a dozen bombers attacked a concentration of about sixty tanks near the El Adem road.

Later twelve tanks approached the wire, but were driven off by the newly installed anti-tank guns. In the evening more vehicles were seen, some of them towing field pieces, and Balfe directed a moonlight shoot, in which the 1st R.H.A. fired more than 400 rounds. When the dust and smoke cleared there was not a vehicle to be seen. Apart from the occasional shelling and the machine-gun and mortar fire the rest of the night was quiet, though patrols sent out from the forward posts could not advance far into no-man’s-land.

During that day enemy planes had been more active in reconnaissance and bombing. Twice they attacked the guns of the 1st R.H.A. and fifteen stukas with strong escort went for the harbour. They were engaged by ack-ack batteries and by the half-dozen surviving Hurricanes of No. 73 Squadron – the only fighters operating from inside the Fortress. Three enemy planes were shot down.

In addition to dropping bombs the enemy scattered pamphlets far and wide. These said:

The General Officer Commanding the German Forces in Libya hereby requests that the British troops occupying Tobruk surrender their arms. Single soldiers waving white handkerchiefs are not fired on. Strong German forces have already surrounded Tobruk and it is useless to try and escape. Remember Mekili. Our dive-bombers and Stukas are awaiting your ships which are lying in Tobruk.

The request went unheeded. ‘No doubt,’ said the Tobruk H.Q. operational summary, ‘owing to the prevailing dust and the necessity to ration water for essential purposes there were no white handkerchiefs available.’ Advising G.H.Q. Cairo of this in its daily situation report, ‘Cyrcom’ said: ‘Leaflets dropped calling on tps [sic] to surrender stop answer –’ The answer consisted of two ‘unprintable’ letters of the alphabet which, though hardly military symbols, expressed the garrison’s reply in the Diggers’ own language.

On Easter Sunday morning, April 13th, the enemy was still busier, though a duststorm cloaked his activities. ‘We saw staff cars and motor-cycles pulled up apparently near a battle H.Q. and we had a crack at them,’ said Balfe later. ‘At the extreme range of 2000 yards our anti-tank gunners hit two motor-cycles and a staff car. But the Germans continued to bring up vehicles and during the morning their artillery began shelling our forward posts. At noon a ‘recce’ plane circled around our company area at about 2000 feet. Late in the afternoon, after a brief bombardment, enemy tanks and infantry again advanced towards the perimeter, but were again stopped by our artillery. Everything indicated, however, that a major assault was coming and that it would be on my company’s front.’

By Easter Sunday afternoon the enemy had gathered a considerable force for this attack. Fortunately Gott’s Support Group had drawn off some Axis troops to the frontier and these had already occupied Bardia and were threatening Sollum. Even so, the R.A.F. in the previous two days had reported more than 200 tanks either near El Adem or on their way to Acroma. On the Sunday afternoon, in spite of bad visibility, pilots had spotted 300 vehicles, including a large number of tanks, astride the El Adem road, four or five miles south of the perimeter. Rommel then had outside Tobruk most of the 5th Light Motorized Division – with well over a hundred German tanks of the 5th Regiment; part of the 132nd Ariete Armoured Division with about the same number of Italian tanks; one motorized and one infantry division, both Italian. These last two straddled the Derna and Bardia roads, but the bulk of the other two had been assembled north of El Adem for attack on Tobruk.

The enemy had substantial superiority in tanks and aircraft, but the half-hearted, abortive moves he had made during the weekend had given the garrison experience, self-confidence – and warning. The troops had been able to take stock and they fully appreciated the significance of the message Wavell sent Morshead that Easter Sunday.

Enemy advance means your isolation by land for time being. Defence Egypt now depends largely on your holding enemy on your front . . . Am glad that I have at this crisis such stout-hearted and magnificent troops in Tobruk. I know I can count on you to hold Tobruk to end. My best wishes to you all.

The attack came that night. By eleven o’clock, after an hour’s heavy mortar and machine-gun fire on the forward posts of Balfe’s company, the enemy was seen moving through the wire east of Post 33. About thirty Germans established themselves just inside the wire, and brought up two light field guns, some mortars and eight machine-guns. Small arms fire could not shift them and it was strongly answered from both inside and outside the wire. The position was serious. If this party stayed there, it could cover a bridgehead and hold the gate open for the tanks.

The platoon commander in Post 33 was a 23-year-old Sydney Lieutenant, Austin Mackell. He was short, slight, quiet and seemed to the rough and ready Diggers under him little more than a schoolboy. But the prompt and determined action he took was that of a seasoned and gallant leader. He knew the enemy must be dislodged, and without hesitation took a corporal and five men to drive them back at bayonet point.

This is the story of their attack as he told it later – after much persuasion:

About a quarter to twelve we set out, Corporal Jack Edmondson, five men and myself – with fixed bayonets and two grenades apiece. The Germans were dug in about a hundred yards to the east of our post, but we headed northwards away from it, and swung round in a three-quarter circle so as to take them in the flank.

As we left the post there was spasmodic fire. Then they saw us running and seemed to turn all their guns on us. We didn’t waste any time. After a 200-yard sprint we went to ground for breath; got up again, running till we were about fifty yards from them. Then we went to ground for another breather, and as we lay there, pulled the pins out of our grenades. Apparently the Germans had been able to see us all the way, and they kept up their fire. But it had been reduced a lot because the men we’d left in the post had been firing to cover us. They did a grand job, for they drew much of the enemy fire on themselves.

We’d arranged with them that, as we got up for the final charge, we’d shout and they would stop firing and start shouting, too. The plan worked. We charged and yelled, but for a moment or two the Germans turned everything onto us. It’s amazing that we weren’t all hit. As we ran we threw our grenades and when they burst the German fire stopped. But already Jack Edmondson had been seriously wounded by a burst from a machine-gun that had got him in the stomach, and he’d also been hit in the neck. Still he ran on, and before the Germans could open up again we were into them.

They left their guns and scattered. In their panic some actually ran slap into the barbed wire behind them and another party that was coming through the gap turned and fled. We went for them with the bayonet. In spite of his wounds Edmondson was magnificent. As the Germans scattered, he chased them and killed at least two. By this time I was in difficulties wrestling with one German on the ground while another was coming straight for me with a pistol. I called out – ‘Jack’ – and from about fifteen yards away Edmondson ran to help me and bayoneted both Germans. He then went on and bayoneted at least one more.

Mackell scrambled to his feet at once, grabbed his rifle, bayoneted one German, but broke his bayonet in doing so. Then he used his rifle as a club. Meantime Edmondson and the others had killed at least a dozen Germans and taken one prisoner. The rest fled leaving their weapons behind them. They had sat resolutely enough behind their machine-guns while the Australians charged, but had cracked at the sight of the bayonet.

Edmondson had continued fighting till he could no longer stand. His mates helped him back to the post, but he died early next morning. Jack Edmondson’s death was a sad blow to his battalion, for he had already made his mark as a man and a leader of men. He was only twenty-six, but considerable experience on his father’s grazing property near Liverpool, New South Wales, had made him older than his years. His heroism did not go unrecognized. He was posthumously awarded the V.C. – the first won by any member of the 2nd A.I.F.

After seeing his men safely back to his own post, Mackell reported the result of the attack to Balfe’s H.Q. Speaking from there to his C.O. (Lieutenant-Colonel J. W. Crawford) he said with expressive brevity – ‘We’ve been into ’em, and they’re running like –––.’

Crawford had already sent two fighting patrols out under Lieutenants W. B. A. Geikie and C. G. Pitman. They had driven back small parties of Germans and had each brought in a prisoner from the 8th German Machine-gun Battalion as well as reports of extensive enemy movement right along Balfe’s front. Crawford now moved his reserve company (under Captain C. H. Wilson) to a position just behind Post 32 ready for a strong counter-attack at dawn.

The offensive action taken by the 2/17th’s patrols, however, had disorganized the enemy’s schedule. Mackell’s charge had routed the German advance guard and it was a couple of hours before they sent forward another force strong enough to hold the gap near 33. About 2.15 a.m. some 200 German infantry moved through the wire and soon established a bridgehead extending several hundred yards inside. At 2.30 Balfe sent up a Very light calling for artillery fire on the ditch, wire and forward posts around 33. Two regiments of the R.H.A. shelled the area heavily; the posts fired everything they had, but this time the Germans could not be dislodged, though they had many casualties. In the moonlight the Diggers in the forward posts saw ambulances picking up wounded some distance outside the wire.

At 5.20 – half an hour before dawn – the first German tanks moved through the gaps their engineers had made, and headed straight for Balfe’s Company H.Q. at Post 32, about half a mile inside the wire. The British gunners were still shelling the area heavily, but the forward companies had orders not to attract the tanks’ attention, to let them pass if necessary, and wait for the enemy infantry.

Consequently, the Australians lay low, even though the leading tank came within thirty yards of Post 32 before it swung to the right and, with a dozen tanks behind it, headed for the town eight miles away. Behind each tank there were groups of fifteen to twenty machine-gunners, some of them riding on the backs of the tanks. They dropped off inside the perimeter, their job being to hold the bridgehead while the tanks pushed on north-east towards the El Adem crossroads, 4½ miles inside.

Soon after 5.45 a.m. thirty-eight German tanks of the 5th Tank Regiment’s 2nd Battalion were forming up for attack about three-quarters of a mile inside the perimeter wire. Meantime, a couple of miles outside, that regiment’s 1st Battalion was moving towards the gap, preceded by field and anti-tank guns and additional German infantry. The attack was going exactly to the plan that had so often shattered defences in Europe. For the 5th Regiment, which had fought in Poland and France, this would be another ‘push-over’. The break-through had been made; now the deep armoured thrust, and then the exploitation by further armoured and mechanized troops who would pour through the gap, fan out behind the defences and roll them up.

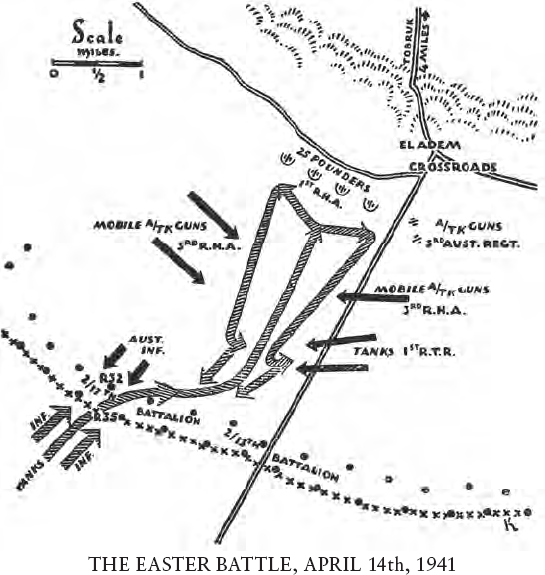

As the 2nd Battalion’s tanks assembled for attack, the dust-cloud they raised could be picked out in the fading moonlight and gathering dawn by the gunners of the 1st R.H.A., whose 25-pounders were behind the embryonic Blue Line about a mile south-west of the El Adem crossroads. At once they switched their fire from the gap to the tanks and increased it as these moved forward. The Germans also came under fire from several of the 3rd R.H.A.’s anti-tank guns, which were dug in behind the forward posts, but it was still too dark for the guns to engage the tanks effectively.

The Germans, however, were already impressed by the British fire. One of their tank officers (Lieutenant Schorm, of the 5th Tank Regiment) wrote later in his diary: ‘Slowly, much too slowly, the column moves forward. In this way the enemy has time to prepare resistance. In proportion as darkness lifts the enemy strikes harder. Destructive fire starts up in front of us now. Five batteries rain their shells on us.’

By this time the German tanks were two miles inside the wire and British guns on either side of the El Adem road were putting down a steady barrage in their path, but they replied with machine-guns and their 75 and 37 mm cannon. ‘The air was lit with tracer shells and bullets until it looked like Blackpool illuminations,’ according to Sergeant-Major Reg Batten, who was commanding one of the 1st R.H.A.’s guns. Later he said:

Their tracers put us right on to them, but so long as they were a mile or so away we couldn’t stop them because they were so well dispersed. They kept their machine-guns going as they moved, but when the Mark IVs used their big ‘75’, they stopped, took deliberate aim at our flashes and then came on again. They seemed to work to a plan. Some fired while the others kept moving. The bulk of their tanks headed straight for the gap between two troops of our guns, but two Mark IVs tried to go round our flank, past the gun where I was.

As they came up within half a mile we engaged them over open sights. At about 600 yards we hit one and then swung the gun to deal with the other. Our first round fell short, but we saw sparks fly as splinters1 struck the side of the tank. We were about to fire again when a 75 mm shell hit us square on the shield. The gun was knocked out and all the crew, except myself, were either killed or wounded. I managed to fire the round that was still in the gun and the tanks turned tail and withdrew. It’s a good thing they didn’t know that we couldn’t fire again and that no other gun near by could have tackled them if they’d kept going. But they turned back and later the tank we’d hit lost its track.

No other tanks got even as far as these. As the main force tried to thrust its way through the line of guns it was stopped short by the barrage. The British gunners had never engaged tanks directly over open sights before but they did not falter. One troop of four guns fired more than a hundred rounds per gun in twenty minutes, as the Germans kept attacking in a determined effort to silence the British fire and smash through. But they had little chance of knocking out guns dug in almost flush with the ground.

At a point-blank range of five to six hundred yards the 25-pounders were irresistible. Seven tanks were knocked out – one, a 22-tonner, which was simultaneously hit by two shells, had a massive turret blown clean off. Leaving several tanks blazing on the battlefield, the survivors swung eastwards and tried to get round the field batteries, but they came under fire from two guns of the 3rd Australian Anti-tank Regiment as they got near the El Adem road. (These two guns claim to have knocked out four enemy tanks in this area, but there seems to be some duplication between their claims and those of 1st R.H.A.) Several more enemy tanks were hit, but managed to struggle back.

Thwarted and battered, the German tanks retired beyond the open sights range of the 25-pounders and the anti-tank guns in the Blue Line. But as they went the 3rd R.H.A.’s mobile anti-tank guns attacked them from both flanks. These guns, mounted on the backs of of 30-cwt. trucks, had no protective armour, but this did not deter their crews. They employed what they later described as ‘mosquito tactics’. At one stage three guns engaged three heavy German tanks. Heading their truck straight for these, the drivers raced across the desert at break-spring speed till they were within half a mile of the tanks; there they swung round, fired half a dozen shells from their 2-pounders and then raced out again. At first the tanks were taken by surprise, but on going in for the second and later attacks the trucks ran into heavy machine-gun and shell fire. Several were hit, but none was put out of action. One had a remarkable escape. A German armour-piercing shell went right through the reserve petrol tank under the driver’s seat without setting the truck on fire. By attacks like these the enemy was harried as he withdrew and several of his tanks were hit.

Before 7 a.m. about a mile south of the Blue Line the Germans rallied and tried to form up for another mass attack, but the British gunners continued to shell them. The tanks were helpless without the anti-tank and field guns and the 8th M.G. Battalion, all of which should have followed them; but there was no sign of these supporting arms. Actually they were still trying to get through, in the face of tactics they had never before encountered. As we have seen, the Diggers in the perimeter posts had not engaged the tanks. Apparently the Germans expected the Australians would give in as soon as the tanks had gone past; some of them had even called on the Diggers to surrender, shouting out that the tanks had broken through and Tobruk had fallen. The answers they received were hardly printable. Once the tanks had moved on, however, the troops in the perimeter posts opened fire on the infantry with everything they had. Some Germans had got through in the darkness, but the rest were now forced to take refuge in the anti-tank ditch outside the wire.

At dawn when the Germans began bringing up anti-tank and field guns Balfe’s men held their fire. ‘As it got light,’ said Balfe, ‘we saw them dragging three anti-tank guns towards the gap. We let them come on till they were within fifty yards of my H.Q. Then we sniped the crews and, though they did fire back, we eventually killed every man. The Germans next brought up some heavy, long-barrelled guns2 to the anti-tank ditch, but we knocked out their crews before they had fired a round. The same thing happened to a 75 mm field gun. Nothing got past us after daylight.’

Meantime heavy shelling of the area outside the wire well south of the bridgehead was disorganizing German attempts to get further reinforcements forward, and the few hundred infantry of the 8th M.G. Battalion, who had slipped through the perimeter posts in the darkness, were soon dealt with. Some of them had taken refuge from the British shelling in shallow wadis on the sloping ground behind the forward posts, but one party had established itself with half a dozen machine-guns in a ruined house a few hundred yards north of Post 32. At 6.30 a.m. Colonel Crawford sent two platoons to clean up this area.

They drove some of the enemy back through the wire and then dealt with those in the ruined house. The attack was made by two sections, led by Sergeant R. M. McElroy, who told me later that, while the other sections gave them covering fire, his men went in with the bayonet. This fire kept most of the German machine-guns quiet and McElroy’s party was able to advance in dead ground until they were within fifty yards of the house. Then they charged, under cover of a hail of grenades. ‘As these burst,’ McElroy said afterwards, ‘the Germans practically stopped firing. Some came running out to surrender; some did not. We got at them with the bayonet. Eighteen were killed and eighteen captured. Few escaped.’

Because of these operations, no guns or infantry came forward to support the German tanks, and by 7 o’clock they were being attacked from all sides by artillery, anti-tank guns and finally British tanks. Long before the first German tanks got through the wire Morshead had taken steps to deal with them. The enemy had made no attempt to conceal the point and direction of his thrust, and during the night, when it became clear that he meant business, the mobile reserve of tanks and anti-tank guns had been moved into position to meet the attack. By dawn two groups of cruiser tanks – half a dozen in each – were disposed to the east of the El Adem road, so that they could attack the enemy’s flank with the early morning sun behind them. They had been ordered to let the enemy armour first batter itself against the field and anti-tank guns, and then to fall on it from the flank. The plan worked well and now, while the Germans tried to re-form for another advance, they came under heavier fire than ever. The British tanks then moved in to attack. From the Germans’ eastern flank five cruisers of the 1st R.T.R., commanded by Major A. E. Benzie, opened fire on them at about 1800 yards. Although they were out-numbered five or six to one, the British closed in to a range of less than half a mile, firing into the mass of milling tanks, which replied strongly. Benzie’s tank was disabled by two direct hits. ‘I ordered the crew to get out and just as they did so, it was hit again and caught fire,’ said Benzie in telling me the story later. ‘I hopped on the back of my second-in-command’s tank and he continued to engage the Germans with me hanging on to the turret, until his tank was hit too.

‘My other tanks kept fighting. During the battle it was almost impossible to tell what was happening. All I could see was round after round of tracer going into the cloud of dust and smoke where their tanks were. But we could tell we had them on the run, and as we followed up, there were four German tanks abandoned on the battlefield.’

By this time the combined British fire plus the failure of his own infantry and guns to appear had been too much for the enemy. As the British tanks, now reinforced by four Matildas, continued their attack, the Germans turned and raced for the perimeter. Evidently they fled in some panic, if the description of the battle written by Schorm, the tank officer already quoted, is any guide. He wrote:

Our heavy tanks fire for all they are worth, just as we do, but the enemy, with his superior force and all the tactical advantages of his own territory, makes heavy gaps in our ranks. We are right in the middle of it with no prospect of getting out. From both flanks armour-piercing shells whizz by at 100 metres a second . . . On the radio – ‘Right turn!’ – ‘Left turn!’ – ‘Retire!’ Now we come slap into the 1st Battalion which is following us. Some of our tanks are already on fire. The crews call for doctors who alight to help in this witches’ cauldron. English anti-tank units fall upon us with their guns firing into our midst. My driver, in the thick of it, says: ‘The engines are no longer running properly, brakes not acting, transmission working only with great difficulty.’

We bear off to the right. Anti-tank guns 900 metres distance in the hollow, and a tank. Behind that in the next dip, 1200 metres away, another tank.

Italian fighter planes come into the fray above us. Two of them crash in our midst. Our optical instruments are spoiled by the dust; nevertheless I register several unmistakable hits. A few anti-tank guns are silenced; some enemy tanks are burning. Just then we are hit and the radio is smashed to bits. Now our communications are cut off. What is more, our ammunition is giving out. I follow the battalion commander.

Our attack is fading out. From every side the superior forces of the enemy shoot at us. ‘Retire.’ We take a wounded man and two others on board and other tanks do the same . . .

With its last strength my tank follows the others which we lose from time to time in dust-clouds. But we have to press on towards the south. It is the only way through. Suppose we don’t find it? Suppose the engines won’t do any more?

Close in on our right and left flanks the English tanks shoot into our midst. We are struck in the tracks which creak and groan. At last the gap is in sight. Everything hastens towards it. English anti-tank guns shoot into the mass. Our own anti-tank and 88 mm anti-aircraft guns are almost deserted. The crews are lying silent beside them. Italian artillery which was to have protected our left flank is equally deserted. We go on. Now comes the gap. Now the ditch. The drivers cannot see a thing for the dust, nor I either; we drive by instinct. The tank almost gets stuck in the ditch but manages to extricate itself after a great struggle. With their last reserves of power the crew get out of range and we return to camp. I examine the damage to the tank. My men extract an armour-piercing shell from the right-hand auxiliary petrol tank. The auxiliary tank – three centimetres of armour plate – is cut clean through; the petrol had run out without igniting. We were lucky to escape alive.

As the German tanks fled through the narrow gap, they had to run the gauntlet of British anti-tank guns dug in near the perimeter. Shells fell and whizzed all around them and six more were destroyed, bringing the total knocked out by artillery, tanks, and anti-tank guns to seventeen.

By 7.30 a.m. the Germans were struggling madly through the wire in complete rout. In a vivid description of their exit Balfe said:

There was terrible confusion at the only gap as tanks and infantry pushed their way through it. The crossing was badly churned up and the tanks raised clouds of dust as they went. In addition, there was the smoke of two tanks blazing just outside the wire.

Into this cloud of dust and smoke we fired anti-tank weapons, Brens, rifles, and mortars, and the gunners sent hundreds of shells. We shot up a lot of infantry as they tried to get past, and many, who took refuge in the anti-tank ditch, were later captured. It was all I could do to stop the troops following them outside the wire. The Germans were a rabble, but the crews of three tanks did keep their heads. They stopped at the anti-tank ditch and hitched on behind them the big guns, whose crews had been killed. They dragged these about 1000 yards, but by then we had directed our artillery on to them. They unhitched the guns and went for their lives. That was the last we saw of the tanks, but it took us several hours to clean up small parties of infantry who hadn’t been able to get away.

This mopping-up had been going on since dawn, as we have seen, but it was the middle of the morning before the last of the Germans were gathered in. One particularly troublesome party of nearly a hundred established itself in a wadi behind Post 28. It was not silenced until Captain C. H. Wilson led part of the 2/17th’s ‘B’ Company against it in a bayonet charge. Some Germans were killed, seventy-five were captured and a few got away, though they were probably picked up later by the patrols from the 2/15th and the Indian Cavalry who collected nearly a hundred more bewildered Germans during the morning.

While the battle was raging between the guns and the tanks there had also been heavy scrapping in the air. Shortly after dawn German and Italian fighters had joined in the battle striving to knock out Tobruk’s few remaining Hurricanes. One Hurricane and two Italian fighters had spun to earth in sheets of fire in the midst of the German tanks, and added their flames to the ‘witches’ cauldron’.

At 7.30, just when the German tanks were making their retreat through the wire, forty Stukas and Messerschmitts attacked the harbour and ack-ack guns. The Hurricanes shot down six; the ack-ack got four. Apparently the Germans had estimated that by this time their tanks would have been approaching the town and the Stuka attack was intended to be the final blow!

In addition to the 12 planes, the Germans left inside the defence 17 tanks, 110 men killed and 254 taken prisoner. But they must have had many more casualties outside the perimeter in the preliminary encounters and in the disorganized retreat, and possibly a number of the tanks that were hit never fought again. Schorm’s company, which had led the attack, lost ten tanks and five 75 mm guns which had been sent up to support it. ‘It went badly,’ he wrote, ‘for the anti-tank units and the light and heavy A.A., but especially for the 8th Machine-Gun Battalion. It is practically wiped out.’ The garrison’s casualties were incredibly few: 20 killed, 60 wounded, 12 missing; two tanks and one 25-pounder gun knocked out; two aircraft shot down.

The Germans were shocked at their defeat. Captured diaries show what they thought. The commander of one troop of tanks wrote: ‘We simply cannot understand how we ever managed to get out. It is the general opinion that this was the most severely fought battle of the war. The survivors call this day ‘Hell of Tobruk’ . . . 38 tanks went into action, 17 were knocked out and many more were put temporarily out of action.’

In their diaries the Germans made various excuses for their failure. The commander of the tank battalion which led the attack wrote:

The information distributed before the action told us that the enemy was about to withdraw, his artillery was weak and his morale had become very low. We had been led to believe that the enemy would retire immediately on the approach of German tanks. Before the beginning of the third attack3 the regiment had not the slightest idea of the well-designed and executed defence of the enemy nor of a single battery position nor of the terrific number of anti-tank guns. Also it was not known that he had heavy tanks. The regiment went into battle with firm confidence and iron determination to break through the enemy and take Tobruk. Only the vastly superior enemy, the frightful loss and the lack of any supporting weapons, caused the regiment to fail in its task.

The prisoners were equally bewildered and bitter. They had expected that the attack would be a walkover and the 8th Machine-gunners had even brought their battalion office truck, complete with files, right to the wire expecting to drive it straight into Tobruk. Characteristic of the prisoners’ comments was that of a German doctor, who had served throughout the campaigns in Europe. ‘I cannot understand you Australians,’ he said. ‘In Poland, France and Belgium once the tanks got through the soldiers took it for granted that they were beaten. But you are like demons. The tanks break through and your infantry still keep fighting.’

That was a prime cause of the garrison’s success. When the tanks broke through, the Australian infantry held their ground and their fire until the German infantry and gunners appeared. The result was that the tanks were left to advance without the support they had expected. The further they advanced, the more intense became the fire which they encountered but could not answer. They were defeated by defence in depth. Checked by frontal fire from the 25-pounders, they found their flanks assailed by tanks and mobile anti-tank guns before they could re-form for another attack.

After the battle Lavarack issued a Special Order of the Day, in which he briefly summed up the causes of the enemy rout. He said:

I wish to congratulate all ranks of the garrison of TOBRUK FORTRESS on the stern and determined resistance offered to the enemy’s attacks with tanks, infantry and aircraft to-day.

Refusal by all infantry posts to give up their ground, and prompt counter-attack by reserves of the 20th Bde, skilful shooting by our artillery and anti-tank guns, combined with a rapid counter-stroke by our tanks, stopped the enemy’s advance and drove him from the perimeter in disorder. At the same time the R.A.F. and our A.A. defences dealt severely with the enemy in the air.

Stern determination, prompt action and close co-operation by all arms ensured the enemy’s defeat, and we can now feel more certain than ever of our ability to hold TOBRUK in the face of any attacks the enemy can stage.

Every one can feel justly proud of the way the enemy has been dealt with. Well done TOBRUK!

This Order of the Day was actually Lavarack’s farewell message to Tobruk. As the Fortress was no longer in touch with the frontier, the place for the desert headquarters was Egypt. Consequently that night Lavarack handed over complete command to Morshead and ‘Cyrcom’ H.Q. was transferred to Maaten Baguish, twenty miles east of Mersa Matruh. There it was absorbed by ‘Western Desert Force H.Q.’, which was soon commanded by Lieutenant-General N. M. Beresford Peirse. He had led the 4th Indian Division in the desert the year before, when the Italians were checked and defeated at Sidi Barrani, and he knew the ground and the problems. This appointment, however, was in no way a reflection on Lavarack, as Wavell made clear. Lavarack, one of the finest military brains Australia has produced, was soon appointed to command the 1st Australian Corps in Syria, and what Wavell thought of his work at Tobruk was expressed in the signal he sent to him after the Easter Battle: ‘Most grateful your invaluable services in stabilizing situation in Cyrenaica.’

_____________

1 Because they had no A.P. (solid armour-piercing ammunition), which the 25-pounders generally use when engaging tanks at close range, the R.H.A. were using H.E. (high explosive shells). With A.P. it could have done much greater damage.

2 These guns were actually 88 mm anti-aircraft guns, which the Germans were using in an anti-tank role, even at this stage. See Chapter 12.

3 The one on April 14th.