IN the wardroom of H.M.S. Decoy one morning early in August 1941, I picked up a copy of the A.I.F. News. Splurged across the front page was an article about Tobruk by the Australian war correspondent, Reg. Glennie. The first sentence ran, ‘Dust, Dive-bombers, Derelict Ships and Death’. Maybe the officers of Decoy left this around deliberately to cheer their passengers as the destroyer churned through the Mediterranean to Tobruk.

For four months these game little destroyers of the R.N. and the R.A.N, had been running this gauntlet. Not all had come through unscathed. Already H.M.A.S. Waterhen and H.M.S. Defender had been sunk, and Nazi bombers were to send other warships to the bottom in the next four months before the land route was opened again.

Meantime the destroyers and a few game little merchant ships, caiques and lighters maintained Tobruk’s life-line, in spite of bomb, shell and submarine. But already the Luftwaffe had made things so hot that the destroyers could only come in when there was little or no moon. In the early months the Germans had not tried dive-bombing at night and the destroyers could afford to brave their high-level attacks. But in July the Germans found that they could pick up the destroyers in the moonlight because of the white foam in their wake, and in the darkness the ships’ gunners could not see the diving planes until it was too late.

We were on the first run of the month and there would be the waning moon to guide the bombers to us as we got near Tobruk, but the crew hoped it would not be bright enough. Their main worry was the last half-hour before dark, when the escorting fighters had left. In this period the Stukas tried to stop the destroyer-ferry so consistently that the run from Sidi Barrani onwards was known as ‘Bomb Alley’.

Dive-bombers seemed as yet a long way off as we lay in the sun on the deck. The day seemed brighter, the Med. bluer and the ship’s wash whiter than ever before. We had left Alexandria at 8.30 a.m., slipping out of a harbour packed with merchantmen and warships, which Axis bombers had never been able to hit. On this trip there were three destroyers, Decoy, Havock and Kingston, each laden with fifty tons of freight and nearly a hundred troops.

Cargo and passengers took up almost every inch of the skimpy deck space. The troops were sprawled out on the cargo and almost in the scuppers, drinking in the sun. Most of them were going up for the first time; some were old-timers, returning for more after being invalided out sick or wounded, and telling newcomers terrible tales of a Tobruk that lay somewhere between purgatory and hell. But there was evidence that it was not so very bad, for amongst us were four Diggers, hitch-hiking back of their own accord. After a few weeks in hospital in Palestine they had scorned convalescent leave, ‘hitched’ their way 400 miles to Alexandria, and ‘jumped’ the destroyer. Strictly they were A.W.L., but they were not going to loiter in a Palestine camp while their cobbers were fighting at Tobruk.

Most of the cargo was cigarettes, mail and ammunition. On the three destroyers there were four million cigarettes – mostly South African brands, which are faintly Turkish – enough to give every man in the garrison the weekly ration of fifty for the next three weeks. As important as these were the dozens of bags of mail – more than three tons of it on our destroyer alone. And then boxes and boxes of ammunition – long, dark-green iron cases with 3.7-inch A.A. shells in them; shorter, squatter green cases of 25-pounder; green-lettered, rope-handled boxes of .303 rifle and machine-gun ammunition; some made in South Africa, some in the U.S.A. Another American contribution was hundreds of cases of dried fruits marked ‘American Red Cross in Greece’. Too late for the Greeks, they had been switched to Tobruk. The rest of the cargo was utilitarian bully-beef, canned cabbage, tinned carrots, dried fruits, a new barrel for a Bofors A.A. gun, a track for a tank, a motor-car engine, and a pile of stretchers for wounded.

Sitting incongruously beside one stack of ammunition was a British officer’s brand new kit. He had been in the Base Ordnance Depot in Cairo for five years and this was his first time in the field. He had fitted himself out well with a bright green canvas valise and stretcher, a blue-painted, brass-hinged wardrobe trunk, a smart new suitcase, and a khaki kitbag. With him was a Scotch terrier!

I tossed him the paper with the glaring lead – ‘Dust, Dive-bombers —’.

‘Not much of a place for a dog,’ I said. ‘Do you take him everywhere?’

‘Yes,’ he replied. ‘I brought him out from England five years ago and war or no war I take him with me. He doesn’t mind the desert, but I don’t know how he’ll like the dive-bombing.’

This dog was not the strangest thing imported to Tobruk. Other British officers arrived during the siege bringing tennis racquets and golf clubs. One canteen ship came in with a large shipment of nurses’ underwear that had been ordered some months before the German counter-attack, when A.I.F. nurses were at Barce. Another time some bright wit in Alexandria shipped to Tobruk twenty-four dozen gin bottles, but he sent them up empty, so that the troops could fill them with ‘Molotov cocktail’. Empty!

About 3.30 p.m. we pass the white sandhills of Mersa Matruh. Two hours later we are level with Sidi Barrani, keeping well out to sea away from bombers based on Bardia. A.A. gunners move to action stations. Then a warning – shouted through a megaphone – ‘Plus six unidentified twenty miles south.’ Guns swing that way – even the 4.7s rise to the high-angle ack-ack position.

Eight specks loom out of the blue, but they are distinctly Hurricanes, coming to cover us as we run through Bomb Alley. The leading plane fires a Very light recognition signal and over they come, 5000 feet up, sweeping back and forth above the three destroyers with the afternoon sun glinting on silver wings and fuselage as they bank and turn.

The destroyers quicken their speed – thirty-two knots now – and spray breaks over the after-deck. On we go, destroyer throbbing under our feet; fighters droning overhead. We are safe while they are with us. An hour later another warning – one flight heads southward to intercept; the other keeps circling above. But soon we see the four Hurricanes returning with eight specks trailing behind them – more Hurricanes – to relieve the others and carry on till half an hour before dark. They must leave then, otherwise they might crack up on landing.

‘Looks as though we’ll be all right to-night,’ says a sub-lieutenant standing beside me. ‘We haven’t been in for nearly a week, so Jerry won’t be expecting us and he hasn’t had a ‘recce’ out. Last month he had a crack at us most nights at dusk after the fighters had gone.’

Finally they wheel away and we continue alone, hoping for the best, but just before dark one lone reconnaissance plane sweeps in from the west, circles once well out of range and goes back to his base with the target for to-night.

The next four hours drag slowly through as the setting moon silhouettes us on a silver sea, turning our wake into a phosphorescent trail. On the deck we wait – salt spray spattering faces and knees as the destroyer plunges into the night. Waiting – waiting – waiting – ears straining for the drone of the bombers.

Then above the roar of engines, wind and sea, from the rear gun-platform an officer shouts through a megaphone: ‘Stand by. Action stations.’ We wait again. Then, ‘Stand by. Enemy aircraft.’

Suddenly we’re snatching at the nearest rail or bulkhead as the destroyer heels over in a wild zigzag and seems to leap forward. On the slippery deck the cargo slides crashing into the scuppers and spray drenches everything.

Above the turmoil that voice again, ‘Stand by. Blitz barrage.’ Behind us a great white swath of wash is even more tell-tale than before, but they’ll have seen us now and the only way to trick them is to zigzag. I look across at Havock – a great stream of black smoke is pouring from her funnels. Then we hear the bomber’s drone and Havock’s guns stab the darkness with red flashes. She rolls over in a 90-degree turn and a hundred yards or so ahead of her a great white water-spout tells us that the Stuka has missed its mark.

Out of the darkness ahead we see two pin-points of light, the harbour lights of Tobruk, shielded from the air but visible to us. We slacken speed. There is no wash now, and a welcome cloud cloaks the moon and other bombers cannot see us.

But they are over Tobruk and are going for the harbour. We can hear the muffled crack of the ack-ack guns and see the flashes of bursting shells high in the sky; only the ‘heavies’ are firing, so apparently the bombers are well up.

We slip in between the lights, past the black ghosts of wrecks, under the lee of the white sepulchre of a town. The ack-ack is still speeding the raider home, but another is coming in – lower. The Bofors are firing too, so it must be well under 10 000 feet. But we have no time to think of the fireworks display above us. As Decoy stops moving two barges and two launches come alongside. Troops clamber over the side, pitching their kitbags ahead of them. Unloading parties swarm aboard and slide ammunition down wooden chutes into one barge, while the rest of the cargo is dumped anyhow into the other. As soon as the troops are off, the crew start bringing wounded aboard in stretchers.

They are getting a warm farewell. One stick of bombs screams down on the south shore of the harbour; the next is closer – in the water 500 yards away. The old hands continue working, unworried, but some of the new ones, like us, pause momentarily, shrinking down behind the destroyer’s after-screen. From the man with the megaphone comes a sharp rebuke – ‘What are you stopping for? Those bloody bombs are nothing to do with you.’

We take no notice of the next two sticks which fall in the town and at last everything is unloaded. The engine throb quickens and the destroyer is lost in the blackness just thirty-two minutes after the barges came alongside. Fifty tons of cargo and nearly a hundred men taken off; fifteen to twenty stretcher-cases embarked, and all in half an hour.

The guns were going again as we left the jetty and went bumping out of the town in a 3-tonner. For the next hour, they were coming over in ones and twos every ten minutes or so. As the drone of one died away, we could hear the next coming in, the greeting of the guns, the rumble of bursting bombs and then the ack-ack’s spasmodic farewell fire. We thought it was a fairly warm welcome but for Tobruk it was just an ordinary night.

Month after month the Navy had been bringing its ships into these dangerous waters and, by doing so, had made possible the holding of Tobruk. When the siege began the garrison had food and ammunition for three, and possibly four, months, but it had to hold for eight. In April and May enemy air attacks on shipping both inside and outside the harbour were so severe that the maintenance of supplies was a most hazardous task. During the first month when ships tried to approach Tobruk in daylight, more than 50 per cent of the cargo vessels were turned back by Stukas and several were sunk. Valiant destroyers managed to slip through at night but Cunningham could not spare enough ships at this time – especially after the losses off Greece and later off Crete – to maintain the supply of anything but absolute essentials. In fact Tobruk’s food reserves would have been seriously depleted if naval and merchant vessels had not evacuated more than 12 000 surplus personnel during the first month.

Even with the garrison reduced to 23 000 the maintenance of adequate supplies was most difficult. Tobruk had no proper unloading facilities, for British bombs had destroyed the main wharf and the other was soon badly damaged by the Luftwaffe and blocked by a wreck. This left only one small oiling jetty which was little more than a pipeline on piles, and so most cargo had to be unloaded into barges or on to half-sunken wrecks. This task was doubly difficult because enemy bombing soon made daylight unloading impracticable.

As it was similarly difficult for shipping to make the run along the Cyrenaican coast to Tobruk in daylight, the garrison during May and June was forced to rely for supplies and reinforcements almost entirely on destroyers which could come in, unload and get out again under cover of darkness. Even if the destroyers escaped bombing this was a perilous run. Their crews never knew what fresh wreck might be lying in the harbour, or whether mines had drifted into or been laid in the narrow channel, or again whether the enemy had put up dummy harbour lights to mislead them. Added to these was the possibility that an enemy submarine would be lying in wait along the route the destroyers had to take in entering the harbour. H.M.A.S. Stuart attacked submarines near Tobruk on two occasions at the end of June.

Undeterred by these hazards, destroyers maintained their ferry service almost nightly, for the Navy knew that without the supplies these brought in, the garrison would eventually have to starve or surrender. None appreciated this more than the troops themselves. Their thanks found expression in the grace I heard a Tobruk padre say one day – ‘For what we are about to eat, thank God and the British Fleet.’ The padre could well have included the anti-aircraft gunners, because without the protection they provided, even the British Navy could hardly have used the Tobruk harbour.

The A.A. gunners’ victory was not quickly or easily won. Rommel used every possible technique to silence them and close the harbour. His airmen tried dive-bombing, high-level bombing, low-level minelaying, mixed bombing – combined dive and high-level, or high-level and minelaying. He went for the ships inside the harbour and outside; by day and night. When bombing proved ineffective, he tried shelling.

To counter these attacks the garrison had only seventy guns in action on April 10th, and by the end of the month only eighty-eight – more than half of which had been captured from the Italians. A third of these were ‘heavies’ and of the remaining light ack-ack guns, half had to be kept outside the harbour area to cover the field artillery.

The guns available were:

Heavy Guns |

Light Guns |

24 3.7 inch (British) |

17 Bofors – 40 mm – (British) |

4 102 mm (Italian) |

43 Breda (all 20 mm Italian except one twin 37 mm) |

These guns were mostly manned by men from Scotland and England. Out of seven batteries, only one was Australian – the 8th Battery of the 3rd Light A.A. Regiment. Few of the gunners had been in action before and fewer still had faced a dive-bomber attack until they came to Tobruk. Some compensation for their lack of experience was provided by the inspiration and soldierly genius of their commander, Brigadier J. N. Slater, a British regular gunner of magnificent spirit, energy and originality. No anti-aircraft commander had been faced with the problem which he had to tackle – that of defeating the dive-bomber with ack-ack guns alone, and, in particular, of protecting these from direct dive-bomber attack. The tactics Slater and his gunners used had to be developed and tried out while the battle was on.

The measure of their success is shown in this: on the first fifty-four days of the siege, the harbour and town area was raided in daylight by 807 dive-bombers; in the last fifty-four days that I was there, there was one daylight dive-bombing attack on this area by one Stuka.

The first fifty-four days in Tobruk were certainly the worst. This initial phase, which lasted from April 10th to June 2nd, was one of intensive dive-bombing, directed first at the ships in the harbour and then at the ack-ack guns. By June 2nd the ack-ack gunners had engaged more than 1550 aircraft and all but 106 of these had come over in daylight.

In the last three weeks of April, there was at least one Stuka raid every day and in spite of the anti-aircraft barrage the harbour became virtually unusable in daylight. When no ships were there, the Stukas bombed jetties on the north shore, general port installations and the town – frequently going for the ack-ack guns simultaneously. To defeat this attack, the guns around the harbour at first put up an umbrella barrage at about 3000 feet.

This was not enough. The German pilots dived through the barrage, or round and under it. They came down as low as 600 feet before dropping their bombs. They were game and, though a few paid, most got away with it. Their main worry at this time was the Hurricanes of No. 73 Squadron, but these were seldom warned early enough to intercept any bomber before it dropped its load.

The harbour area could be protected only by more effective ack-ack fire. This was provided by ‘thickening the barrage’ with more guns, as they became available, and by spreading their fire over the area between 3000 and 6000 feet, instead of concentrating it at one level. Thus Stuka pilots had to face a belt of fire for 3000 feet of their dive. To counter their trick of coming down along the edge of the barrage and then diving under it, this was made to swing backwards and forwards across the harbour, so that a pilot never knew where its edge would be. He might start his dive clear of the barrage and suddenly find that it had swung right into his line of flight. Similarly gunners used to vary the height of the barrage. Some days its ceiling was 5000 feet; on others 7000, and pilots were frequently tricked. These two improvements made the barrage much more effective and any Stukas that did brave their way through it came under direct fire of two or more of the twelve Bofors placed around the harbour. After the end of April these ‘killed the bird’ more often than not, if a Stuka came really low.

Stung by the force and accuracy of this fire, the Germans turned their dive-bombers against the ack-ack guns themselves. In a fierce attack on April 27th, they went for the four heavy gun-positions, each of which had four 3.7-inch guns. The attack began with a number of medium bombers and fighters (JU88s and ME 109s) coming in very high to draw the fire from the heavy guns. While the 3.7s were blazing away at 20 000 feet, fifty JU87s stole in well below them in four formations, each of which went for one heavy-gun position.

From two of these positions, the JU87s were spotted and engaged on their run in. As the guns swung on to them, each formation split into four groups of three or four and down they came – attacking each of these two gun-positions from four points of the compass. With the concentration of fire broken up, each gun had to deal with three or four Stukas diving directly for it.

It took nerve to stand up to the attack but every gun kept firing as the bombs came down. From the moment the fire bombs exploded, the crews were smothered with dust and smoke, but they fired on without faltering even though they could see nothing. In spite of this, the Stukas went through with their dives, but not one bomb landed on either position. Even the near-misses – fifty and a hundred yards away – did no damage, for the guns were well dug-in and had strong parapets. Not one man on these eight guns was killed or wounded.

On the other two heavy-gun positions it was a different story. The JU87s that attacked one site were spotted as they came in, but the gunners did not engage them very effectively. On the other site the gunners were still busy dealing with the high-level attack when the first of the Stukas’ bombs burst in the middle of the circle of four gun-pits, which were only about fifteen yards apart. The Stukas had all dived straight out of the sun and the gunners, disconcerted by this and the surprise, took cover as soon as the first bombs landed. The pilots had an open go. Practically every bomb was placed right on the positions. To make matters worse, the guns were not well dug-in and their parapets were not substantial. Five men were killed and forty-one wounded. Two guns on each site were put out of action for two days, and other ack-ack equipment was damaged.

The comparison between the fate of these and the other two gun-positions taught a grim but encouraging lesson. If the guns fought the dive-bombers all the way down their crews were reasonably safe. If they did not, both guns and crews would be lucky to escape.

Slater immediately instructed every battery that in the face of dive-bombing no one who had a weapon to fire was to go to ground. Every gun must keep in action and all those who were not manning an ack-ack gun must engage the diving planes with rifles or light automatics. Every gun was to be dug in as deep as possible and protected by a parapet capable of withstanding a 1000-pounder, landing ten yards away.

These measures helped the gunners to look after themselves fairly well and with each attack they gained more confidence and skill. Guns were damaged from time to time, but, from April to the end of October at least, not one was completely knocked out, and none was put out of action for more than a day or two. On only three other occasions did the dive-bombers silence a position during an attack and by the end of May the gunners had the upper hand.

The anti-aircraft guns, however, had to do more than defend themselves. Rommel had so many planes that he could afford to launch one attack strong enough to keep all the heavy guns occupied while he sent another against the harbour. Naturally if all the heavy guns were to be engaged in beating off direct attacks on their own positions, they could not keep up the harbour barrage. This danger was averted primarily by deception. A number of dummy gun-sites were established near the main heavy ack-ack positions. These were remarkably well constructed – so well that you could drive within a hundred yards of a dummy site without realizing that it was not genuine. They had dummy guns, dummy men, trucks, and ammunition dumps. Moreover, the dummies were fitted with a special mechanism that produced ‘gun-flashes’ and dust-clouds when the nearby guns were fired. By having real guns in a position one day and dummy guns there the next, the deception was completed.

The result was that the Stukas, diving at dust-clouds from which flashes came, attacked dummy sites as often as real ones. As the danger of direct attack on the guns was thus virtually halved, the gunners could concentrate on their primary task of maintaining the harbour barrage. To make sure of this, Slater ordered that no gun-site was to use more than one gun for its own defence except in very unusual circumstances, but it took considerable courage on the gunners’ part to keep three of their four guns firing the barrage when they knew that Stukas were diving straight for them. To give better protection from low-diving attacks, however, one light ack-ack gun was placed near each position.

This system worked magnificently. The barrage was maintained, the guns were defended, and the Germans wasted a lot of their bombs on the dummy sites. On one occasion thirty-five JU87s and eight JU88s attacked the harbour and seven heavy-gun sites. Three of the sites attacked were dummies and each of the other four defended itself with only one of its two guns. (As part of the deception policy, some sites at times had two real guns, and two dummies.) The harbour barrage suffered very little and the enemy had three planes shot down and six hard hit.

Frustrated in his attempts to silence the guns and close the harbour in the first month, Rommel turned his bombers against Tobruk’s water resources, in the hope of ‘thirsting’ the garrison out. Tobruk’s main supply came from two distilleries on the south side of the harbour, which purified sea-water, and from two pumping stations in the Wadi Auda (two miles west of the town), which raised sub-artesian water that was more than a little brackish. These were all operated by the 2/4th Field Park Company, even though its only trained engineer was a staff-sergeant, E. D. Wakeham. An additional supply was provided by a pumping station in the Wadi es Sehel, which formed part of the western boundary of the defences. This plant, housed in an underground room with blue-painted walls and a red-tiled floor, was actually in no-man’s-land. Nevertheless, troops regularly went out there for a shower. This was never bombed – apparently because the enemy hoped to capture it intact and not, as the Diggers believed, because the enemy himself pumped water from this source. The other plants, however, were subjected to heavy and repeated attacks during May and early June. Luckily none was hit.

Finally the enemy was induced to abandon his attacks by further clever deception. After one attack on the distilleries a camouflage section poured dirty oil over the buildings to make it appear that they had been hit. They finished the job in half an hour and the reconnaissance plane that came over later evidently saw black shadows that looked like gaping holes in the roofs of the buildings. They were not directly attacked again.

The attacks on the water supply were part of Rommel’s attempt to bomb Tobruk into submission after his tank attacks failed. He was able to keep all shipping – except very small caiques and other minor craft – out of the harbour in daylight during the rest of May, but the ack-ack guns still defied him. All through that month the battle between dive-bombers and gunners went on, and frequently the German Radio claimed that the Tobruk ack-ack had been silenced.

In the Berlin Nationblatt on May 12th a German war correspondent, named Billhardt, gave a glowing and optimistic account of the air attacks on the harbour. He wrote:

Over Tobruk the sky is seldom silent. The sound of our motors continually terrifies the Tommies, chases them to their guns and forces them to hang the sky with steel curtains and black anti-aircraft clouds, until dive attacks by our Stukas with bombs and machine-gun fire destroy them or force them to take cover. The anti-aircraft artillery of Tobruk enjoyed our highest respect – once. Then the Stukas dropped their bombs, and since then the anti-aircraft shelling from Tobruk has become very much weaker. After each attack the younger pilots are twice as eager next day to fly still more madly into the middle of the anti-aircraft barrage – to get on to their objectives still more exactly. To batter Tobruk till it is ready for storming will be a nice piece of work.

Herr Billhardt’s pilots had ample chance to prove these words good when Rommel made an all-out attempt to silence the ack-ack guns in the week ending June 2nd, but they found that the Tobruk defences were stronger than ever. There were now twenty-eight heavy guns in action compared with sixteen in April and the harbour was ringed with twelve Bofors guns instead of six. The gunners even manned the 3-inch dual-purpose gun on the deck of the gunboat H.M.S. Ladybird, which lay half-sunken in the harbour. She was the victim of a dive-bomber raid, but a tattered White Ensign still flew proudly from her mast.

That week’s blitz began on May 26th with an attack by six JU87s on a new heavy-gun position on North Point – the headland north of the harbour. The crews of these four guns had never been in action before, but they braved the Stukas, blew one to bits with a direct hit, and watched a nearby Bofors bring down another.

On the 29th the dive-bombers switched their main attack to the harbour, but the gunners scored their biggest victory to date. Out of thirty dive-bombers, four crashed, another probably crashed, and four more limped home, unlikely to fly again. But their bombs sank two lighters and one small ship.

Undeterred by their losses, the Stukas came back on June 1st for another defeat. Twenty-four out of forty JU87s went for the heavy guns while the rest attacked the harbour. Twelve dived on the North Point guns, but in the face of their fire, few came below 3000 feet, and one that did was destroyed in mid-air. Not one bomb fell within 150 yards of the guns and some pilots sheered off and dropped their bombs in the sea. Altogether four were shot down for certain, and at least six more were badly damaged.

The final round was fought next day, when the Germans sent in sixty Stukas – thirty of them against the impudent North Point guns. To see whether the planes really went through with the attack, they sent three Henschels to observe the results of the bombing from a safe height above the barrage. But, Henschels or no Henschels, the pilots would not face the anti-aircraft fire.

In the first two raids of this week they had come down one after the other in steep dives at an angle of about 70 degrees. On June 1st they had dived steeply but had been forced to release their bombs above the barrage – too high for accuracy. On June 2nd they changed their tactics and tried shallow diving from different directions, but this made no difference to the gunners. Once again the North Point guns blew a plane out of the sky and the bombs fell even farther from the mark than before. The Germans did not press home their attack, but this raid was just as costly as that of the previous day. Four JU87s were shot down, four were probably destroyed and four more damaged.

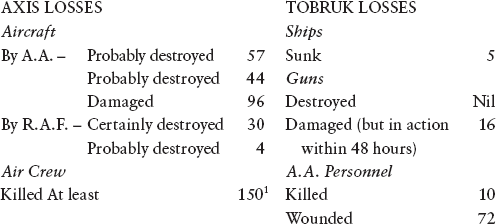

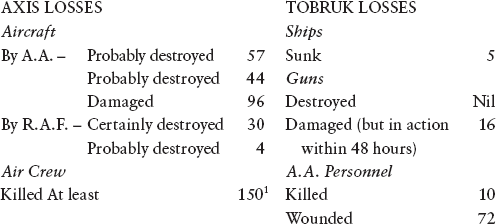

June 2nd saw the end of the first phase of the battle between the gunners and dive-bombers and the scoreboard then showed:

The enemy’s most serious losses had been in dive-bombers and their crews, since 80 per cent of the planes shot down were single-engined JU87s. For a few weeks the Germans used twin-engined JU88s for dive-bombing as well, but these were sitting shots for the gunners. On April 20th, when eleven of them dive-bombed the town, the R.A.F. shot down four, the ack-ack got three and probably destroyed two more.1

Unfortunately for Rommel, his most courageous pilots – those who dived lowest – were the ones generally brought down, and almost invariably they crashed to death. Thus by June 2nd he had lost the pick of his German dive-bomber crews, and thereafter had to make increasing use of Italians, who were neither as skilful nor as courageous. With the Russian campaign soon absorbing nearly all the aircraft and pilots Hitler could spare, Rommel could no longer incur losses as severe as those his airmen had suffered at the end of May.

For all these losses Rommel had little to show. His aircraft had sunk in Tobruk harbour only two small naval vessels, two troop-transports and one small cargo ship. In addition a larger number of vessels was sunk outside the harbour approaching or leaving Tobruk. Some of these sinkings would have been avoided if G.H.Q., Cairo, had given earlier heed to Tobruk’s request that no ships, other than very minor craft, should be sent in during daylight.

In defying the dive-bombers, the Tobruk anti-aircraft gunners did more than keep the harbour open and destroy enemy aircraft. They gained a moral triumph and set an example for Allied gunners and enemy pilots everywhere. For the first time in this war, ack-ack gunners showed that Stukas could be beaten by men who stood to their guns.

_____________

1 See Chapter 19. The Tobruk A.A. Command’s estimate of the number of planes shot down was very conservative, and the actual enemy plane losses were probably 50 per cent greater than those claimed. Hence this estimate of personnel killed.