CHAPTER 8

ADOLF HITLER AT YPRES

One soldier serving in the ranks of the Imperial German Army was destined to become the most notorious man in history. Adolf Hitler was serving in the ranks of the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment, known as the List Regiment after its first commander. Hitler was to become very familiar with the distant aspect of the town of Ypres, his war started near the town in 1914 and four years later it would also end there in October 1918 when he was temporarily blinded by a British gas shell. Twenty four years later during one of his rambling monologues which were later collected together and published as Hitler’s Table Talk, the Führer recalled the first tantalizing glimpse of the town which would remain within the grasp of the German armies but which would never fall to them. ‘My first impression of Ypres was—towers, so near that I could all but touch them. But the little infantryman in his hole in the ground has a very small field of vision.’

We are also fortunate that we also have Adolf Hitler’s letter to Ernst Hepp which provides us with a surprisingly detailed account of the reality of service in a front-line unit during the early months of the Great War:

‘Then morning came. We were now a long way from Lille. The thunder of gunfire had grown somewhat stronger. Our column moved forward like a giant snake. At 9am, we halted in the park of a country house. We had two hours’ rest and then moved on again, marching until 8pm. We no longer moved as a regiment, but split up into companies, each man taking cover against enemy airplanes. At 9pm, we pitched camp. I couldn’t sleep. Four paces from my bundle of straw lay a dead horse. The animal was already half decayed. Finally, a German howitzer battery immediately behind us kept sending two shells flying over our heads into the darkness of the night every guarter of an hour. They came whistling and hissing through the air, and then, far in the distance, there came two dull thuds. We all listened. None of us had ever heard that sound before. While we were huddled close together, whispering softly and looking up at the stars in the heavens, a terrible racket broke out in the distance. At first it was a long way off, and then the crackling came closer and closer, and the sound of single shells grew to a multitude, finally becoming a continuous roar. All of us felt the blood guickening in our veins. The English were making one of their night attacks. We waited a long time, uncertain what was happening. Then it grew guieter and at last the sound ceased altogether—except for our own batteries—which sent out their iron greetings to the night every guarter of an hour. In the morning we found a big shell hole. We had to brush ourselves up a bit, and about 10am there was another alarm and, a guarter of an hour later, we were on the march. After a long period of wandering about we reached a farm that had been shot to pieces and we camped here. I was on watch duty that night and, about one o’clock, we suddenly had another alarm; and we marched off at three o’clock in the morning. We had just taken a bit of food, and we were waiting for our marching orders, when Major Count Zech rode up: “Tomorrow we are attacking the English!” he said. So it had come at last! We were all overjoyed; and after making this announcement, the Major went on foot to the head of the column.’

The ‘English’ which Major Count Zech was referring to consisted of elements of Worcester Regiment in position between the village of Gheluvelt and the town of Ypres. Also in the vicinity were some companies of the Scottish regular regiment, the renowned Black Watch. Although this was not a full scale battle it was to prove a bitterly fought encounter. Hitler only ever fought in two engagements and, not surprisingly, the events of October and early 1914 were destined to feature heavily in the pages of Mein Kampf.

The List Regiment had well and truly received its baptism of fire on 29th October 1914 and the casualties suffered by the List regiment in October 1914 were severe. Hitler’s description of the regiment’s first taste of combat confirms the ferocity of the engagement: ‘And then followed a damp, cold night in Flanders. We marched in silence throughout the night and as the morning sun came through the mist an iron greeting suddenly burst above our heads. Shrapnel exploded in our midst and spluttered in the damp ground. But before the smoke of the explosion disappeared a wild ‘Hurrah’ was shouted from two hundred throats, in response to this first greeting of Death. Then began the whistling of bullets and the booming of cannons, the shouting and singing of the combatants. With eyes straining feverishly, we pressed forward, guicker and guicker, until we finally came to close-guarter fighting, there beyond the beet-fields and the meadows. Soon the strains of a song reached us from afar Nearer and nearer, from company to company it came. And while Death began to make havoc in our ranks we passed the song on to those beside us: Deutschland, Deutschland Über Alles, Über Alles In Der Welt.’

Hitler and the List Regiment acquitted themselves well during the fight around Gheluvelt, but casualties, amounting to two thirds of the strength of the regiment, were very high – even by Great War standards. Hitler’s description of the battle for Gheluvelt is detailed at great length in his letter to Ernst Hepp. The fight clearly made a huge impression on him and he went to some trouble to ensure that Herr Hepp had all of the details. The situation was fluid and confused, and although trenches were beginning to appear on the battlefield, this was one of the last occasions on the Western Front on which armies would manoeuvre in the open: ‘Early, around 6am, we came to an inn. We were with another company and it was not till 7am that we went out to join the dance. We followed the road into a wood, and then we came out in correct marching order on a large meadow. In front of us were guns in partially dug trenches and, behind these, we took up our positions in big hollows scooped out of the earth; and waited. Soon, the first lots of shrapnel came over, bursting in the woods, and smashing up the trees as though they were brushwood. We looked on interestedly, without any real idea of danger No one was afraid. Everyman waited impatiently for the command: “Forward!” The whole thing was getting hotter and hotter. We heard that some of us had been wounded. Five or six men brown as clay were being led along from the left, and we all broke into a cheer: six Englishmen with a machine gun! We shouted to our men marching proudly behind their prisoners. The rest of us just waited. We could scarcely see into the steaming, seething witches’ caldron which lay in front of us. At last there came the ringing command: “Forward!”

We swarmed out of our positions and raced across the fields to a small farm. Shrapnel was bursting left and right of us, and the English bullets came whistling through the shrapnel; but we paid no attention to them. For ten minutes, we lay there; and then, once again, we were ordered to advance. I was right out in front, ahead of everyone in my platoon. Platoon-leader Stoever was hit. Good God! I had barely any time to think; the fighting was beginning in earnest! Because we were out in the open, we had to advance guickly. The captain was at the head. The first of our men had begun to fall. The English had set up machine guns. We threw ourselves down and crawled slowly along a ditch. From time to time someone was hit, we could not go on, and the whole company was stuck there. We had to lift the man out of the ditch. We kept on crawling until the ditch came to an end, and then we were out in the open field again. We ran fifteen or twenty yards, and then we found a big pool of water One after another, we splashed through it, took cover, and caught our breath. But it was no place for lying low. We dashed out again at full speed into a forest that lay about a hundred yards ahead of us. There, after a while, we all found each other. But the forest was beginning to look terribly thin.

At this time there was only a second sergeant in command, a big tall splendid fellow called Schmidt. We crawled on our bellies to the edge of the forest, while the shells came whistling and whining above us; tearing tree trunks and branches to shreds. Then the shells came down again on the edge of the forest, flinging up clouds of earth, stones, and roots; and enveloping everything in a disgusting, sickening, yellowy-green vapor We can’t possibly lie here forever, we thought and, if we are going to be killed, it is better to die in the open. Then the Major came up. Once more we advanced. I jumped up and ran as fast as I could across meadows and beet fields, jumping over trenches, hedgerows, and barbed-wire entanglements; and then I heard someone shouting ahead of me: “ln here! Everyone in here!” There was a long trench in front ofme and, in an instant, I had jumped into it; and there were others in front of me, behind me, and left and right of me. Next to me were Württembergers, and under me were dead and wounded Englishmen.

The Württembergers had stormed the trench before us. Now I knew why I had landed so softly when I jumped in. About 250 yards to the left there were more English trenches; to the right the road to Leceloire was still in our possession. An unending storm of iron came screaming over our trench. At last, at ten o’clock, our artillery opened up in this sector. One—two—three—five—and so it went on. Time and again a shell burst in the English trenches in front of us. The poor devils came swarming out like ants from an ant heap, and we hurled ourselves at them. In a flash we had crossed the fields in front of us, and after bloody hand-to-hand fighting in some places, we threw [the enemy] out of one trench after another. Most of them raised their hands above their heads. Anyone who refused to surrender was mown down. In this way we cleared trench after trench.

At last we reached the main highway. To the right and left of us there was a small forest, and we drove right into it. We threw them all out of this forest, and then we reached the place where the forest came to an end and the open road continued. On the left lay several farms—all occupied—and there was withering fire. Right in front of us, men were falling. Our Major came up; guite fearless, and smoking calmly; with his adjutant, Lieutenant Piloty. The Major saw the situation at a glance, and ordered us to assemble, on both sides of the highway for an assault. We had lost our officers, and there were hardly any noncommissioned officers. So all of us, every one of us who was still walking, went running back to get reinforcements. When I returned the second time with a handful of stray Württembergers, the Major was lying on the ground with his chest torn open, and there was a heap of corpses all around him.

By this time, the only remaining officer was his adjutant. We were absolutely furious. “Herr Leutnant, lead us against them!” we all shouted. So we advanced straight into the forest, fanning out to the left, because there was no way of advancing along the road. Four times we went forward, and each time we were forced to retreat. From my company, only one other man was left besides myself, and then he, too, fell. A shot tore off the entire left sleeve of my tunic but, by a miracle, I remained unharmed. Finally, at 2am we advanced for the fifth time; and this time, we were able to occupy the farm and the edge of the forest. At 5pm, we assembled and dug in, a hundred yards from the road. So we went on fighting for three days in the same way, and on the third day the British were finally defeated. On the fourth evening we marched back to Werwick. Only then did we know how many men we had lost. In four days our regiment consisting of thirty-five hundred men was reduced to six hundred. In the entire regiment there remained only thirty officers. Four companies had to be disbanded. But we were all so proud of having defeated the British!’

Despite all the inherent evils of the job, Hitler had a love of soldiering which never left him, but even wearing his most rose-tinted glasses, he must have known that his audience was unlikely to be taken in by a description of eager units advancing towards each other singing patriotic songs. It is certainly true that in the intensive battles of the early war units would sing a snatch of ‘Der Wacht Am Rhein’ which was the proscribed means of verbal recognition in the early stages of the war, but this activity had a distinct purpose. Hitler’s less dramatic description of the withdrawal of the List Regiment from the line is much more convincing: ‘After four days in the trenches we came back. Even our step was no longer what it had been. Boys of seventeen looked now like grown men. The rank and file of the List Regiment had not been properly trained in the art of warfare, but they knew how to die like old soldiers.’

Adolf Meyer of the List Regiment writing in his diary recalled one of the defining moments of the battle. This was the instant when Colonel List was killed by a British shell. It is not surprising that in all the confusion of battle there are differing accounts of the death of the Colonel. According to Meyer, List was killed fighting in the very front ranks. His diary entry records the effects of the fighting: ‘Only a few regiments have had to give such a heavy toll in blood in their first fight, the proud List Regiment had melted down to the strength of a battalion, the brave regimental leader, Colonel List, felled by a direct hit in the furthest forward line.’

Hans Mend writing in his book, gives a completely different account of the circumstances of the Colonel’s death. Mend was an eye witness and recalled how he was on his way to see Colonel List, who was then engaged in setting up headquarters in the recently captured Gheluvelt chateaux. As he approached the building Mend witnessed what he described as a ‘three heavy English shells’ crashing into the building.’ According to Mend this was the real cause of the death of Colonel List: ‘I could see nothing any more, and could no longer breathe for dust. Hearing cries of help coming from the chateaux, Mend rushed forward and was able to describe the scene as an eyewitness in which he attempted to assist in the rescue effort which was being performed by a group of Saxons, a few telegraph operators sprang immediately to the aid of the wounded. At once, one cried out: “The Bavarian colonel is also dead!” In my horror, I left my horse unattended, and sprang to the side of Colonel List, now covered by a tent flap. I lifted this away and saw that blood welled from his mouth. Our brave commander, who was a true leader of his troops, was no more.’

On Sunday, 2nd August 1914, a twenty-five year old Adolf Hitler was amongst thousands of people gathered at the Odeonsplatz in Munich. The crowd joined in exuberant enthusiasm for the war and Heinrich Hoffman was on hand to record the scene. He later identified Hitler as a figure in the crowd.

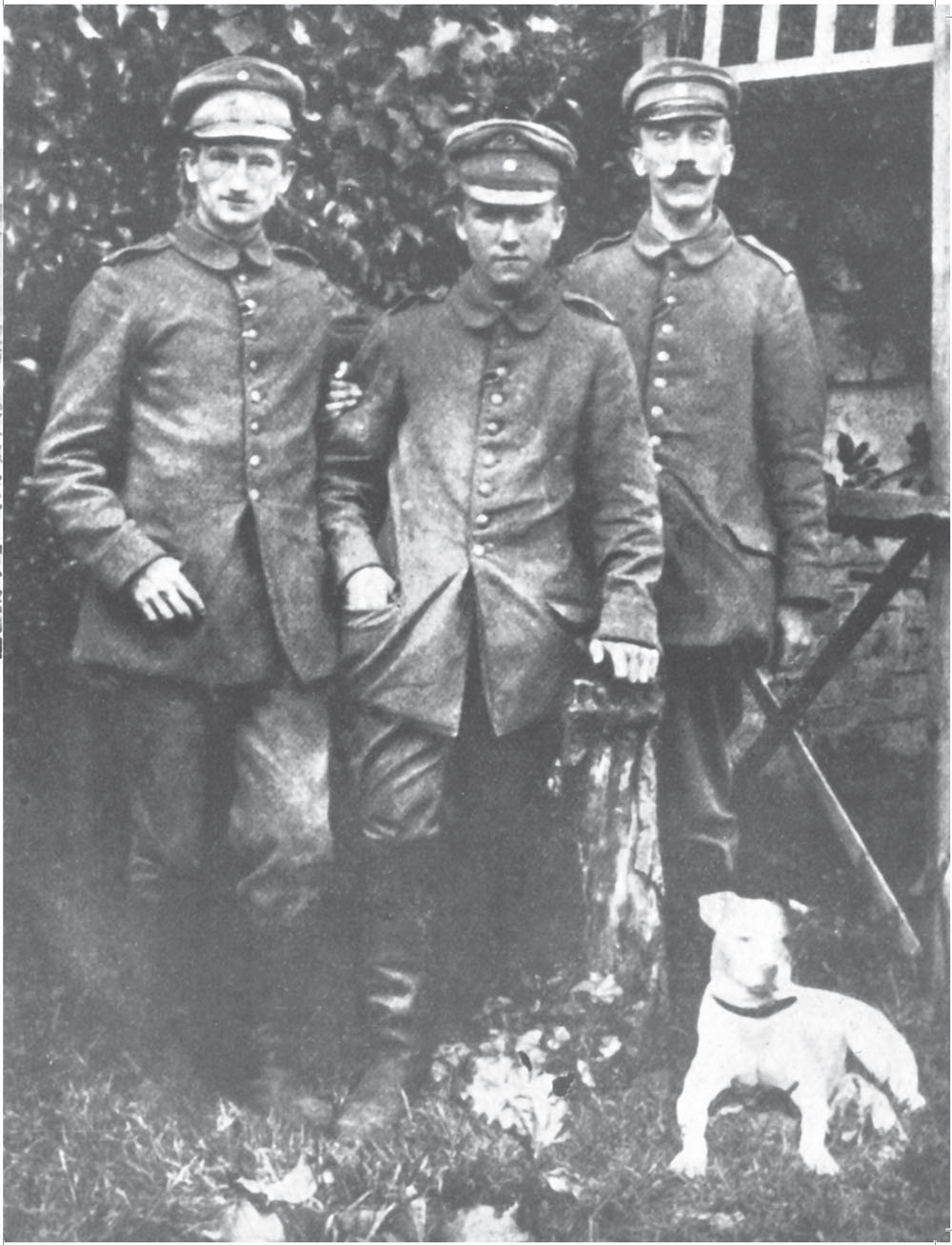

The earliest known photograph of Regimentsordonnanzen (Regimental Orderlies) and messengers Ernst Schmidt, Anton Bachmann and Adolf Hitler. Seated at Hitler’s feet is the English Terrier named Foxl, who came to be Hitler’s most treasured companion. The photograph was taken in April 1915 in Fournes.

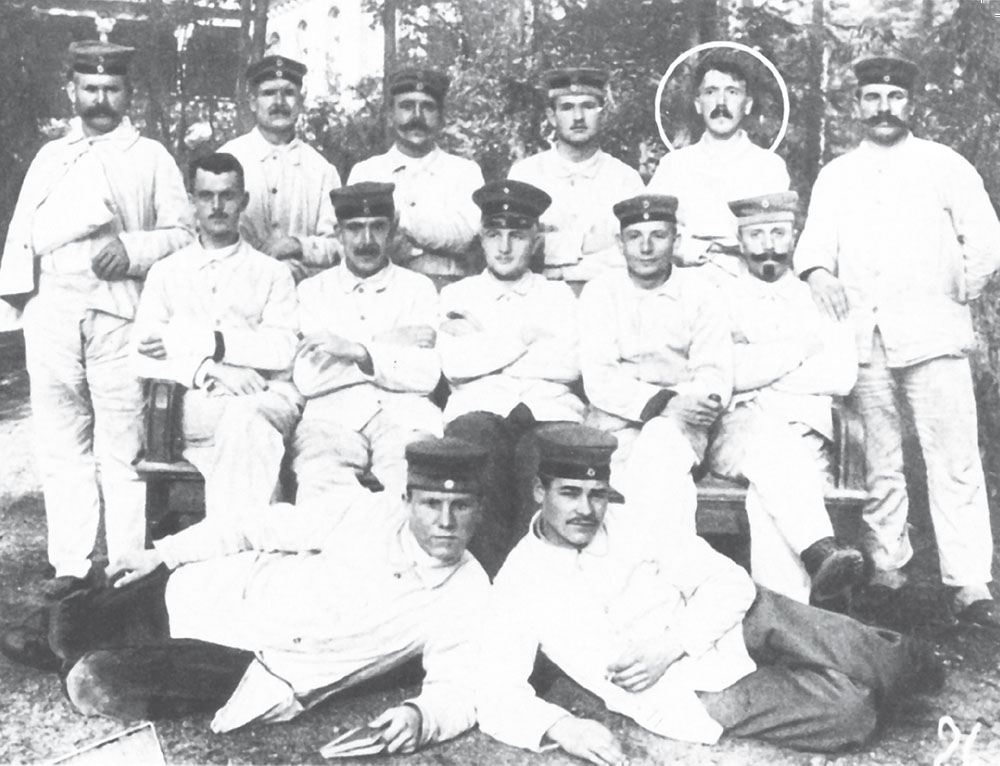

Hitler with his comrades in September 1915, at the Regimental Command Post in Fromelles. Photograph by Hans Bauer: (Front row, left to right) Adolf Hitler, Josef Wurm, Karl Lippert, Josef Kreidmayer. (Middle row, left to right) Karl Lanzhammer, Ernst Schmidt, Jacob Höfele, Jacob Weiss. (Back row) Karl Tiefenböck.

The badly damaged town of Fromelles, where the Regimental Headquarters of the 16th RIR was situated from 17th March 1915 to 27th September 1916. Even in the rear areas, such as this, long-range shelling was a constant menace.

In this photograph taken at the beginning of September 1916, Hitler is seen alongside his colleagues and his faithful dog Foxl in the rear area at Fournes. (Front row, left to right) Adolf Hitler, Balthasar Brandmayer, Anton Bachmann, Max Mund. (Back row, left to right) Ernst Schmidt, Johann Sperl, Jacob Weiss and Karl Tiefenböck.

Orderly Sergeant Max Amann (left) pictured at La Bassée station in March 1917.

The conditions in the waterlogged frontline trenches near Fromelles were appalling, as this photograph from May 1915 graphically demonstrates. The men of the 16th RIR lived and fought in these conditions.

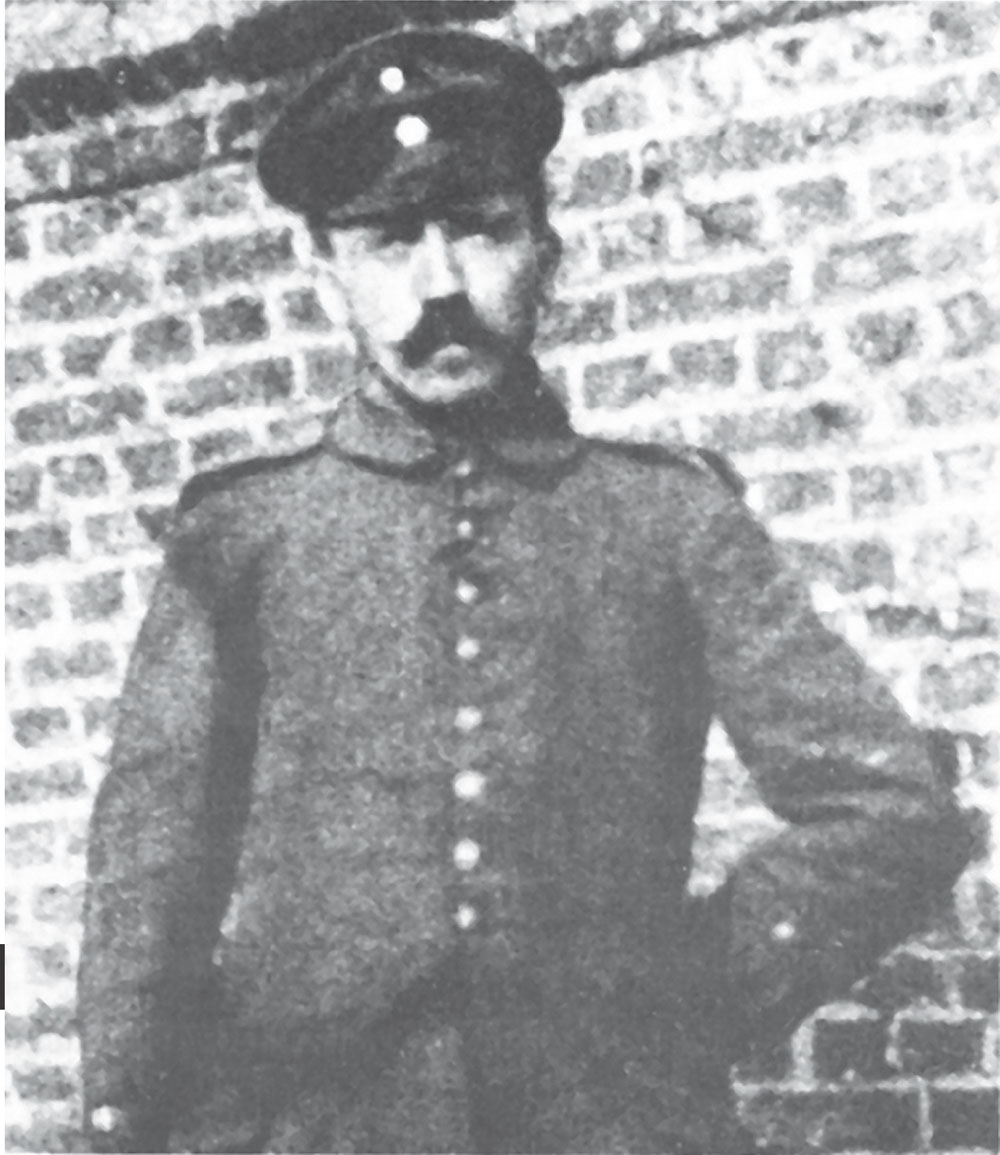

Adolf Hitler in 1916 in the rear area at Fournes.

Adolf Hitler and Karl Lippert in mid-1915 in Fournes.

Adolf Hitler, then a battalion-messenger, seen in May 1915 with his rifle slung over his shoulder. Hitler was in the process of delivering a message. This photograph first appeared in the Official Regimental History of the 16th RIR.

Hitler, accompanied by Max Amann and Ernst Schmidt and aides, after the victory over France on 26th May 1940. The group were photographed on their tour to visit the positions they had occupied during the Great War in Flanders.

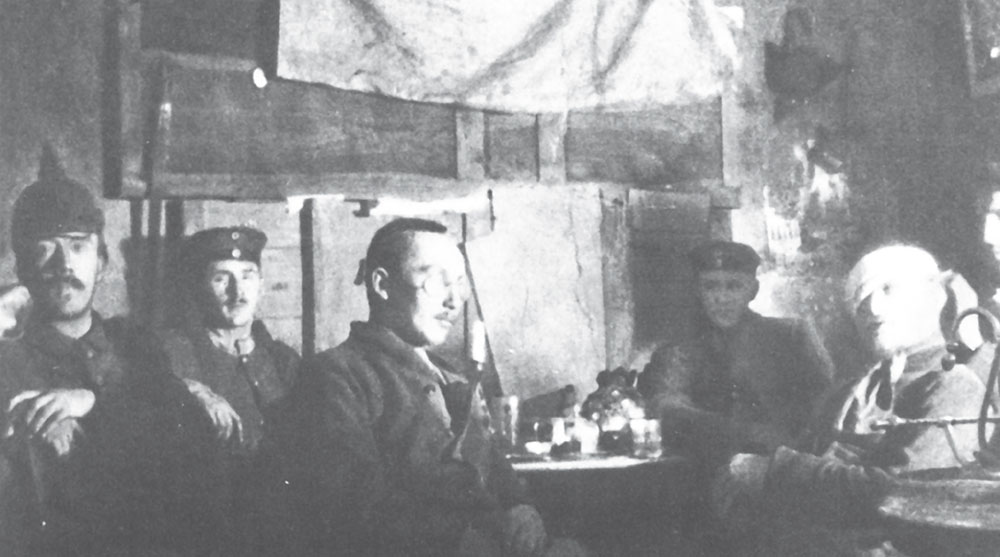

Hitler (left with helmet), and next to him Balthasar Brandmayer, pose for the camera in a bunker near the frontline section of Reincourt-Villers in September 1916.

Hitler with his comrades in May 1916 in Fournes: Balthasar Brandmayer (front), (left to right seated) Johann Wimmer, Josef Inkofer, Karl Lanzhammer, Adolf Hitler, (left to right standing) Johann Sperl, Max Mund.

Hitler with (right to left) Max Amann, Wehrmacht adjutant Gerhard Engel, Ernst Schmidt and adjutant Julius Schaub on 26th April 1940 at the same location in Fournes, some 24 years later.

Hitler on 26th October 1916, in the Prussian Association of the Red Cross hospital in Beelitz near Berlin, where he was brought after being wounded on 5th October 1916.

Hitler pictured in 1915.

Hitler pictured in 1919.