I’m a woman and I’m gonna have my damn way because I’m gonna demand it. I’ve been in these damn streets all by myself a long time. Don’t nobody wanna treat me like the way I wanna be treated. I’ve turned the other cheek so many fuckin’ times that I’m sick and tired. And it hurt, and it ain’t easy, and I don’t strut—but there ain’t nobody no better than this person.

I’ll let y’all know why I’m like this. Let me tell my story.—Tina

Carrying a sixteen-ounce can of discount malt liquor bearing the imprint of her always freshly applied lipstick, Tina projected a persona of defiant lumpen femininity. She dressed to the hilt in color-coordinated silk, satin, and leather outfits and identified herself publicly as an alcoholic. She spent most of her time and energy, however, in pursuit of crack, shoplifting from the stores on Edgewater Boulevard and throughout the Mission District. She also demanded money aggressively or seductively from friends, acquaintances, and strangers.

Her preference for crack and alcohol and her aggressive style of panhandling initially brought her into Reggie’s orbit in front of the A&C corner store. He cultivated a hyper-virile persona—“I’ve got fourteen kids; you know I love that pussy”—and he fantasized about “pimping” Tina:

I’d sell a bitch’s pussy in a minute. I’ll make Tina sell hers. “Hey, Tina, get him! [pointing to an imaginary customer] Get that money, girl!” She go around the corner, come back, and she got the money for me.

Tina, for her part, accepted Reggie’s treats of vodka and crack but responded to his sexual advances with vehement curses.

To counter her obvious physical frailty, Tina regularly erupted into rages when disrespected. These outbursts sometimes attracted the police. For example, she spent four days in the county jail for smashing windshields in a McDonald’s parking lot, after a security guard ordered her to stop panhandling. She was soon in trouble again when the security guard in the neighboring parking lot of the Discount Grocery Outlet prevented her from helping customers unload their shopping carts into their cars. He claimed, with some justification, that her primary goal was not to earn tips but to run off with the groceries. Tina responded by scratching the side of a brand-new SUV with the shards of a crushed Coke can on her way out of the lot.

Tina’s all-night crack binges with Carter, Sonny, and Stretch increased in frequency in the now all African-American I-beam camp. She returned less often to her cousin’s apartment to rest and bathe. She derived a visible joy of living from the company of her new homeless friends and disliked getting high alone. When we stayed overnight in the encampment, she often proposed group activities. In the intimate glow of a spluttering candle, her face would light up with pleasure as she pulled out a set of dominoes or clapped the opening lines to her favorite parlor game, Slow Boat to China. She was fun to be with, so long as she was well stocked with crack and alcohol.

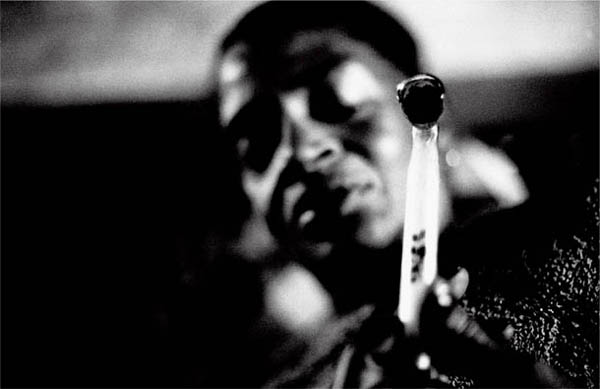

Despite the chronic level of violence against women on the street, Tina celebrated her femininity. Whenever she lit up her crack pipe, she draped her arms around whatever man was closest to her in a spontaneous expression of affection. She often pulled out a little compact, even in the candlelight, to apply lipstick, lip liner, mascara, and concealer.

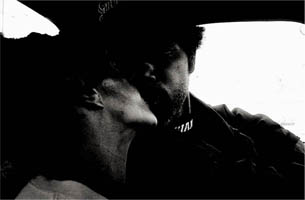

Tina enjoyed being the center of attention, and, at first, all the men were energized by her presence. She began focusing her attention on Carter, who was openly courting her. He increased his crack consumption in order to spend more time with her and became jealous whenever she talked for too long with another man. He would call out threateningly from a few yards away, in the voice of an ambiguously playful/abusive parent, “Tina! Come over here. . . . Don’t make me come over there and get you.” At night by the campfire, he would sneak kisses on her cheek in between shouts and threats over who had smoked too much of whose crack. On one occasion, in a pique of feigned rage, he grabbed the patent leather purse strap wrapped around Tina’s shoulder and dangled her in the air until the purse strap snapped.

Reggie was jealous of Carter and increased his offers of alcohol and crack, which Tina continued to accept. It appeared that she was setting the two men on a collision course. She eventually resolved the ambiguity by smashing a portable radio over Reggie’s head inside the corner store amid a shower of curses. Reggie responded by punching her squarely in the jaw, yelling, “Bitch! Nobody does me like that!” Tina sprawled backward over a display rack of potato chips, bringing several shelves of canned goods and fast-food boxes crashing to the floor with her. Shouting in Arabic, the Yemeni storekeeper ran from behind the cash register, striking at both Reggie and Tina with a broom. Dazed, Tina struggled to her feet, bags of Doritos crunching beneath her. Her lower lip swollen and bleeding, she staggered out of the store and ran, limping, to her cousin in the projects.

In the back alley afterward, Reggie rubbed the side of his face, also bleeding from the fight. He said he was worried that Tina might have given him HIV with her scratches. Tucking in his ripped shirt and straightening his jacket, now torn at the shoulder, Reggie returned to insulting her femininity in classically lumpen patriarchal terms:

Sorry-assed bitch had it coming. She’s lucky we weren’t outside, because I would have pounded her. Bitch is crazy! That’s her way of showin’ love. Nobody ever looked at her as a woman. They look at her as a bitch.

Spread her legs to have nine fuckin’ kids, and they all got took. She don’t have none of them.

I got fourteen kids, and I’m separated from all the women, but it doesn’t mean I’m gonna neglect the kids. My family have all the kids. Each and every one of my sisters took a kid.

Tina was furious at the Yemeni storekeeper, who, she claimed, “kicked me in the head when I was down.” She was careful, however, not to involve Carter in the conflict and instead invoked the protection of her own close male family members, “to go take care of Reggie.” Her eldest brother, a bank robber turned Christian minister, lived several hours away in Modesto, a mid-sized town in California’s Central Valley. Her youngest brother, affectionately nicknamed Dee-Dee, had been released from prison recently; he was married to a drug treatment counselor and lived with her in the suburbs. Tina’s eldest son, Ricky, was about to be released from prison.

No follow-up violence occurred, however, and within a few days, Reggie and Tina were once again panhandling at the entrance to the corner store from which they had both been “86’ed [banned from entering].” There was no longer a flirtatious undertone between them. By lashing out at Reggie, Tina had asserted her commitment to her budding relationship with Carter, but she had accomplished this on her own terms, without becoming dependent on Carter by demanding that he confront Reggie. When talking about the fight, Tina referred to her capacity for rage as an uncontrollable character trait: “I blacked out. I go off. I do that. I did wrong.” This was her way of carving out a safer space for herself, in reaction to the misogyny and sexual objectification of women on Edgewater Boulevard.

Two weeks later, Reggie was arrested for brandishing a broken handgun during an argument over a crack purchase in the alley behind the corner. Everyone referred to the arrest as his “third strike” and anticipated that he would receive a life sentence under California’s new mandatory sentencing laws. His mother and four of his eleven brothers and sisters came to his hearing to plead leniency from the judge. He eventually received an eight-year sentence on a plea bargain and disappeared from the Edgewater Boulevard scene.

Soon after the fight with Reggie, Tina began accompanying Carter on his nighttime scavenges, pushing his shopping cart and helping him fill it with anything that had potential resale value, primarily aluminum cans and copper metal. On one of their sorties, they recovered two Victorian mahogany chairs, upholstered in white with elaborately carved armrests. Carter referred to them as “the loveseats I got for Tina.” They became the centerpiece of the I-beam camp, which, under the influence of Tina’s scavenging skills, became an obstacle course overflowing with things for sale: coffee tables, settees, slabs of plywood, rolled-up rugs, assorted lampshades, ceramic figurines. For privacy from Sonny, Stretch, Al, and temporary overnight guests, Tina and Carter divided their section of the camp into two (roofless) “bedrooms,” each about ten feet square, bounded by a double-decked perimeter of couches in various states of decay. At the center of their bedroom, Tina placed a shiny, red 1960s rotary dial telephone. It sat on an upturned Pampers box covered by a white lace antimacassar. Sitting in their loveseats smoking crack late into the night, the affectionate couple would gently clink their glass pipes together in a formal toast before each inhalation. Tina would drape her legs over Carter’s lap, cuddling his head into the nape of her neck.

Tina had been living as an independent woman on and off the street for almost five years since her last serious love relationship, with the father of her youngest daughter, Jewel. One of her survival strategies was to cultivate a diverse set of male “friends” willing to give her money, drugs, food, and other resources in exchange for sex. Carter’s version of masculine control and romance, however, required her sexual fidelity. He did not share Reggie’s pimp fantasy. He began insisting that Tina stop “partying” with her “men friends.” Tina seesawed between exhilaration over falling in love with Carter and fear of becoming subservient to a man and losing her core income-generating strategy:

We fight because Carter’s very jealous. He think everybody want me. But then, shit! They know that I’m his woman. And they known that I ain’t gonna suck they dick for no fuckin’ crack or for no money. Fuck that!

If I do it, he ’a never know. It’s gonna be somebody. . . . It ain’t gonna be [somebody] black. Unless they a black rich man. Shit! I got white friends. They pick me up. I got a black friend in a Cadillac that picks me up. And he’s not cheap at all.

And I’m gonna keep my friends. I mean, he’d never know. I never tell him. Because I have to always look out for my damn self. Never let a person—a man—know every damn thing about you. Shit! I’d never succeed in life.

Tina knew she could not depend on Carter, because, as she put it, “He ain’t nothing but a righteous dopefiend.”

The men around Carter were outraged by Tina’s insistence on autonomy. Stretch was especially misogynistic:

She’s got the mentality of a man. Carter’s being scandalous with her. He doesn’t keep her in check. We’re doing her wrong. If she acts like this out there [pointing to the boulevard], she could get her ass whooped.

It ain’t right for her to be around men like this. She doesn’t have no female friends. She told me that she hates bitches. And she’s just a skinny ugly bitch herself who puts her twat out, but still wants to stick her tongue down a man’s throat.

That twat gotta be good for Carter to put up with her shit.

Stretch also engaged in sex work with men, but he did it secretly in San Francisco’s skid row neighborhood, the Tenderloin. Eventually, Stretch left the I-beam camp, preferring to hustle full time downtown.

Tina’s instrumental relationships with men, even with those for whom she felt affection, illustrates the complex continuum between altruism and instrumentality that haunts all male-female sexual relations and intimate feelings but becomes more visible under conditions of urban poverty and masculine domination. Many social scientists have argued against the possibility of altruistic relations in sex and love (Zelizer 2005). The debate over the moral economy of intimate relations entered the mainstream of anthropology as early as the 1920s, when Marcel Mauss, the founder of gift exchange theory, criticized Bronislaw Malinowski, the pioneer of participant-observation methods in anthropology, for categorizing the presents that husbands offer to their wives in the Trobriand Islands as “pure gifts.” Mauss reinterpreted these intimate, private exchanges “as a kind of salary for sexual services rendered” and asserted that they “throw a brilliant light upon all sexual relationships throughout humanity” (Mauss [1924] 1990). Tina’s mode of interacting with men openly merged affection with money. She had grown up surrounded by sex workers and pimps. As a precocious child, disobeying her mother, she empathized with friendly neighbors in distress:

Tina: When I was a kid, we stayed on Hayes and Fillmore; that’s where the ho’s used to walk up and down on our street.

I used to let them in through our door, right at the bottom of the stairs. ’Cause they used to be runnin’ from the police and stuff, and I likeded them. I felt sorry for them ’cause they pimps kick them and all that . . . beat them with clothes hangers and shit, kick them in they ass. Uh-huh!

There was three favorite ones that I liked. I used to see them with they miniskirts on, and they pimps. They start giving me money for candy and shit. I look out the window for them. And if I didn’t see them, I be very scared. One would be coming out of the car, you know, runnin’. And when they rang the doorbell, you know, to hide from the pimp or the police, I come and let them in.

I was about eight. My mother used to be [angry voice], “Don’t answer that door!”

I’m like, “That’s my friend, Ma.”

Jeff: Did you understand what they were doing?

Tina: I knew they was whoring. I’m not stupid at eight. At eight, I knew! I seen them every night. And my brother, he was a player [pimp], my oldest brother and my first cousin too. They both dead now.

That was when the Black Panthers and all that shit was out. I knew about all that too.

Tina needed to be emotionally prepared to talk about her past. When references to her childhood surfaced in casual conversation, she would usually stop in mid-sentence, swallow hard, apologize, and stare through the windshield in awkward silence. She often broke these flashbacks of childhood trauma by exhaling from her cigarette, swigging on a beer, and reversing the focus of the conversation by asking us questions about our own intimate lives. Sometimes she would simply say, “I’m not ready to talk about that now . . . some other time.” Tape recordings of Tina’s life story had to be planned days in advance. She would dress up for the occasion, asking us to drive her to a private location. Months or years later, she would sometimes recollect affectionately the special occasions “when I shared my story with you.”

Jeff’s fieldnotes describing the events on the afternoon just before we tape-recorded her life story for the first time convey the banality of sex, sex work, violence against women, and interpersonal abuse. His notes also make reference to a diverse range of routine survival imperatives, joys, and everyday violences that the homeless encounter on any given day: fleeing law enforcement, losing shelter and all their possessions, exchanging and demanding favors, scavenging from the garbage, encountering bonanzas of useful junk, negotiating hostile social service bureaucracies, dismissing public stigma, ignoring sexual and scatological displays, anticipating potential assaultive violence, seeking legal employment, and getting high repeatedly.

Later in the day, speaking into the tape recorder, Tina revealed the deeper childhood foundations of her habitus. Sex, affection, and income were logically intertwined in the gray zone of poverty and abandonment that had engulfed her early years. She learned to mobilize her sexuality and femininity with personal charisma. Her account of coming of age in the segregated inner city during the 1960s clarifies more than just a psychological understanding of how her personality was affected by intimate violence. It reveals the limits of disciplinary biopower in shaping lumpen female subjectivity on the street. Gender power relations, household instability, poverty, racism, and abusive violence are foregrounded; and seeking material compensation from men for sex emerges as the commonsense adaptation of a vulnerable child struggling to decipher the turmoil among the men and women around her. In her search for adult love and affection, Tina learned the practical value of sex. Three decades later, she reflexively defined the worth of all relationships with males, whether sexual or not, through the gifts they generated—money, food, drugs, trinkets, or clothes.

Tina is waiting for me, as promised, for our life history “tape recording date.” She jumps into the car and starts telling me that Caltrans [the California Transit Authority] evicted them from the I-beam camp yesterday at 2:00 P.M., true to the NOTICE TO VACATE sign that had been posted last week on the chain-link fence. She, along with Carter and Sonny, lost all her possessions except for a few blankets they had managed to hide behind the ice machine at the Pizza Hut down the boulevard.

Tina asks me to sign a welfare job search form because yesterday a social worker rejected her application, citing “lack of proof” that she had sought work from twenty different employers in the past month. “Shit! I asked everyone I know. What else they want me to do?”

She wants me to stay overnight in the camp because she lost her alarm clock in the eviction and does not want “to have to stay up all night” for fear of “not making it to the welfare office on time.” I agree, and she gratefully hands me a strand of pooka beads, wrapped in clean tissue paper: “Jeff, give these to your girlfriend, from me, Tina.”

Today happens to be the day when homeowners in the neighborhood are supposed to dispose of bulky items that do not fit in garbage cans. Mattresses, chairs, rugs, carpets, computer monitors fill the sidewalks. Seeing this, Tina orders me to stop the car, exclaiming gleefully, “Let’s go shopping, Jeff!”

“You know I’m a pack-rat,” she giggles, grabbing a garbage bag full of clothes, a broom with a Christmas wreath attached to its handle, and an orange porcelain horse. I enthusiastically load a sleeping bag and two blankets into my trunk for her, and she sings, “Jeff is shopping with me.” After forty-five more minutes of “shopping,” my car is stuffed.

We settle back into the crammed front seat, and Tina loads her crack pipe, a tiny Grand Marnier airplane-sized cocktail bottle with the bottom drilled out. Before lighting up, she asks if I see any police. Peering into my driver-side mirror, I see the reflection of a homeless man, dressed in rags, sprawled on his back. His body is twisted awkwardly with his head turned to the side. “Is he dead?” I ask, alarmed. Tina squints in the man’s direction and exclaims, “That’s horrible! Get your camera, Jeff. He’s masturbating.”

Instead I drive off and we park by a baseball diamond. Hyper from the crack, Tina immediately jumps out, squats right behind the open car door, and urinates into the gutter. Embarrassed, I avert my eyes and quickly adjust my rearview mirror to give her privacy.

A middle-aged woman Tina recognizes approaches us. She talks extremely slowly as though heavily medicated and asks me a series of precise questions—my name, my address, and where we are going. After she leaves, Tina explains, “She was looking out for me. She think you a trick [prostitute’s customer] and want to make sure where I be if something bad happens.”

Before letting me turn on the tape recorder, Tina announces that she wants me to buy beer for both of us and cigarettes for her. The woman behind the counter in the store is dreadful to us, curling her upper lip and spitting out the answer when we ask for prices.

Back in the car, Tina comments that once again I was mistaken for a trick, this time by the hostile cashier. These incidents prompt Tina to begin her childhood story on precisely this theme, so central to her survival strategies in life:

“I learned about pullin’ tricks when we was living with my auntie. She was babysitting us. I was about twelve.

“A man would come by and she say to me and my sister, ‘I gotta use the bathroom’ and he’d go in with her. She would do whatever and come out with money; but before she went in she didn’t have no money.

“My auntie make good money from her mens. And so I learned, like if we didn’t have no money or nothin’, I be [meek voice], ‘Auntie, why don’t you call that man that came over last week and gave you some money?’

[gruff voice] “ ‘Girl! You shut up. What you talkin’ about?’

“I’m like [meek voice again], ‘You know . . . that man. When we didn’t have nothin’ and he came over and he gave you some money and borrowed somethin’ to drink and had some cigarettes? Won’t you call him, auntie? He a nice man.’ ’Cause my auntie’s men friends would come in the house and like, touch my booty. You know, like [deep voice], ‘Hey, girl’ and be pattin’ my ass. All the time they was getting a free one. But I wasn’t knowin’ it.

“But I didn’t start dating till I was sixteen. It was at the Presidio army base. My girlfriend Darlene from school, she turned me on to the army mens and I just went wild. ’Cause it was different—and they had money and I could drink all I wanted and go to the officers’ club and just have a ball, right? Like I’m a grown lady. I was sixteen and I was hangin’ at the Presidio with the army mens.

“That’s when I first fucked, at the barracks with Darryl Dexter. I was just drunk and havin’ fun. But I didn’t even know if he bust my cherry ’cause I was drunk. But then afterwards I start feelin’ it, right?

“And he brought me home with a wet pussy and I went straight to the bathtub. And my mother said, ‘You don’t come home and wash your nasty ass. You wash your ass where you lay it at.’ And when I asked my mother for some bus fare and cigarettes, she say, ‘Don’t you never come beggin’ round here when you stay out all night and come home with no money. You call that man right now. What’s his number?’

“I called him, and my mother told him, ‘Don’t you ever keep my daughter out and not give her nothin’. She goes to school and blah, blah, blah.’

“He came over and he brought me some money and my mother some money. He say, ‘Here, this is your bus fare for school for next week, and here is your lunch money.’ It was probably about twenty dollars for me and probably twenty dollars for my mother.”

Jeff: “So when you lost your virginity you got paid for it?”

Tina: “Not right then, but my mother made sure I did afterwards. That’s when I felt that she gave me the okay to prostitute. I didn’t know it was prostitutin’. I just knew that she gave me the okay to sell my body. That I could fuck.”

Jeff: “When did you start pulling tricks?”

Tina: “Every time I go see Darryl Dexter. He had to give me some money because I couldn’t go home. I stayed in the barracks. I was a wanderin’ Jew. A child that didn’t know shit and learnt it all by herself. [sirens passing]

“My mother got me smoothed on birth control pills. I was going to the clinic down there. Right over there on Edgewater and Palmer.

“And my doctor used to say, ‘Your mother, she is so worried about you, about somebody abruisin’ your body.’ I’m like, ‘Don’t nobody abruise my body.’ ’Cause I didn’t let him just fuck me hard and shit. I’m like, you have to be nice and soft to me. And gentle.

“Yeah, he wasn’t rough and all that shit like a hound dog. No, uh-uh! No.”

A generational disconnect between Tina and her mother, Persia, over interpretations of romance exacerbated Tina’s sense of maternal betrayal. As a single woman overwhelmed by poverty, with a house full of children and no male breadwinner to help her, Persia was desperate to find income and stability for her vulnerable daughter. She also sought to redeem Tina’s honor by having her fulfill the romantic patriarchal dream of marrying the man to whom one loses one’s virginity. Instead, Persia further confirmed her daughter’s commonsense understanding that sex and affection require remuneration, because Persia tried to pay Tina to marry Darryl Dexter. This violated Tina’s late-1960s ideas about romantic free choice and played on her sense of suffering from maternal neglect and rejection:

She pay me to call Darryl Dexter. He stay in Philadelphia, and he wanted to marry me. He beg her, and she was gonna make me marry him, but I wasn’t in love with him.

I was just a teenager, and she was going to sign papers for me to marry him. And I say, “You just tryin’ to get rid of me. I ain’t goin’ nowhere!” She was gonna marry me off.

Tina described growing up as a bored, lonely girl seeking adult attention and pocket change for treats in front of the local corner store after school let out. This was long before she began purposely selling her body, when “I was still a virgin but I was just used to standing with my hand on my hip. I didn’t know shit.” Tina did not describe her childhood years in a linear narrative. Her tape recordings are a confessional outpouring of vulnerability that triggered repeated flashbacks and sudden changes in affect. In mid-sentence one account of sexual assault and molestation often interrupted another. We had to edit her text more than most for clarity, and it was difficult to punctuate because of its stream-of-consciousness leaps occasionally interspersed with rapid-fire irony.

Careful attention to Tina’s vocabulary also reveals how the standard distinctions between rape, sex work, and consensual sex are inadequate to understand sex on the streets and in homes that are dominated by unstable and often predatory men and women. Jeff repeatedly interrupted Tina to ask her to explain the terms she was using interchangeably to describe a range of socially taboo and often violent or nonconsensual sexual activities that she had experienced by the time she was a teenager: “date,” “ho’,” “trick,” “walk the stroll,” “walk the street,” “mess with,” “be with,” “have some fun,” “fast-fuck,” “manhandle,” “molest,” “abuse,” and “abruise.” Her account also reveals that long before she understood what was happening to her sexually, she had already learned the effectiveness of violence and rage as a means of self-defense. Furthermore, she was taking a wide range of legal and illegal psychoactive drugs during these early adolescent years.

Tina: I was kidnapped on Haight Street by this man that looks like Isaac Hayes. He had a bald haircut.

We had went together inside the store. But after a while his conversation wasn’t about shit. He grabbed me like on the Flintstones, how Fred put the dog out the window, and threw me in the car and I was like, resistant. And I couldn’t get out of his car ’cause he had those locks up in front—the electric locks. [long pause]

But he manhandled me till I was in his house. He was a big ol’ guy and I was skinny. [long pause] I probably still know where that house is.

Jeff: How did you meet this guy?

Tina: I was on the corner at the store. I had came from school and I was lookin’ for a date.

Jeff: A date? Does that mean you were selling your body?

Tina: Not then. I was only fourteen. This time I was just talking and sharin’ words and shit, like we was on a date. I didn’t start trickin’ till I was sixteen—I just told you, with Darryl Dexter.

So he says, “Wait, I’m not gonna hurt you.” So I calmed down. He said, “I just wanna have a little fun with you, and you can be on your way. . . . I just need me a woman right now. . . . And you look like a nice lady.”

I’m like, “Yeah?” But he got out a bag of weed and some truinals, them blue ones. Them worser than the reds, right? And I was droppin’ pills at that time, stealin’ them from my mother. . . . And heaven knows I know how to take them.

He said he had been watchin’ me for the longest time. Going to school, catchin’ a bus, and shit. I don’t know if he knew where I lived. But at that time I had ran away from home. I was living with this army mans and his wife.

Jeff: You mean, Darryl Dexter?

Tina: No, this was another army man. He was married and he was a trip! He molested me in my sleep. I woke up. He was suckin’ my pussy.

Jeff: Wait. I don’t understand, but first finish the kidnap story about the bald guy. Did he abuse you?

Tina: He didn’t fuck me, if that’s what you mean. He didn’t get nothin’. He didn’t molest me. He beat me. ’Cause I snap, Jeff. Just like my mother. I went crazy. He really wanted my body.

I was scared but I tried to play along. But I kept prolonging it and not comin’ out of my clothes . . . saying [meek voice], “I’m a virgin, I’m not even fifteen.”

So he kept slapping me—[speaking faster] slappin’ me slappin’ me and slappin’ me. And he had a waterbed and there was some scissors, and I took them scissors and I just punched a hole in that waterbed. And I start tearing his house up—everything! I kicked his floor model TV with some tennis shoes and glass is splattered. I even cut my feet, Jeff. And I was electric-shocked.

He said, “That tiny bitch! My TV!”

I tried to jump through the big picture window in his room but I just bounced right back off of it ’cause it was plastic. I was tearing his house up and finally he just opened his door and I ran to the police and told the police everything. They came back to investigate. But I let it go because I didn’t want my mother to know because I had ran away from home. I was stayin’ in the Haight with this lady and her husband from the Presidio. We used to take acid. They called it “window pane.”

My girlfriend Darlene from school stayed there too. All the time I wasn’t knowin’ that she liked ladies. But she always would greet me with a kiss and a hug and that’s how I normally greet because I’m raised up in church and that’s how we do each other. We hug and kiss. Not for the sex, you know.

Jeff: So Darlene was having an affair with the woman?

Tina: And also with the man.

Jeff: Who? The husband who was molesting you in your sleep?

Tina: Yeah. This was after I got kidnapped and they had sent me to the psych ward. They was giving me pills, Thorazines, and I was sleepy from them. But I woke up . . . but I act like I was asleep, right. But I ain’t goin’ to lie, it was good, too, though. But I was scared ’cause his wife threw this other fuckin’ bitch through the window.

Jeff: What!

Tina: Mmm-hmmm. . . . All the time he was molesting me in my sleep he was also fuckin’ around with the neighbor, the lady who lived upstairs who had a little girl and a boy. And after his wife found out that her husband was sleeping with that lady she plotted and plotted. And we always in cahoots together, right? So we all set it up and she caught them one night together. And it was it! Right through the window. That bitch’s arm was hangin’ off. Her skin was just hangin’ down bleeding.

Jeff: How terrible!

Tina: Yeah! I got emotional. Hell, I think I had a nervous breakdown and I went home after that. I told my mother what I wanted to tell her and then I went to bed. But then she put me in juvenile detention for two weeks during Easter vacation ’cause I started to be just a little bad-ass girl, right? And she thought I was fit to give up my pussy. She thought that I was out there fast-fuckin’. But I wasn’t.

I was only fourteen and I was just . . . I was so stingy. I would just kiss. Ain’t nobody gettin’ in my pants so I was just kissin’, Jeff. ’Cause I was thinkin’ that if a man get in my pants, I’m ’a have a baby.

Because my grandmother and my mother, they used to say that if you be with a man, they roll on you, you gonna end up pregnant. That was what they told me. And shit, I’m stupid. I’m believing them.

My mother didn’t take out time with explaining me all that. So I was a virgin up until I was sixteen because I was afraid to get pregnant. And I didn’t get pregnant till I was twenty and I got married then.

I didn’t want no damn baby ’cause I babysitted . . . [long pause] and my cousin who would molest me as a kid . . .

Jeff: Your cousin also molested you?

Tina: Mmm-hmmm. My first cousin. My mother raised him. It was my aunt’s only child. My dead aunt that tricked in the bathroom and shit. She dead now—cirrhosis of the liver. It was her son and he died of cirrhosis too. He molested me.

He used to press my hair and all that. Get me ready for school and wash me up. He used to take good care of us because my mother always worked and went to school. She was always lookin’ for a better job, you know, to take care of us. Even on welfare she still had to work.

He would put me in the bathtub and everything. I had to take a bath every morning because I peed the bed. Every time! I was a little girl, seven or eight.

I didn’t never really know what was going on till I got older, but I wake up one time and he was gettin’ up off me and I was soaking wet. I remember that he was pumpin’ on me. And I remember that his dick was in me. And I was peeing and I would wake up when I start peeing. And I be scared and he was getting up off of me.

Then I started bein’ so bad that he start shyin’ away from me because I realize what he done. ’Cause I caught him that morning but he probably had been doing it all the time.

I didn’t say nothin’ until I was twenty-seven. I said, “I remember when you used to fuck me and I pussy wet. I was a kid.”

And then I told him, “I loved you so much I didn’t want you to get married.” I hated his wife. But I loved her twins, right. They had twin girls, Jeanine and Jeanette.

I told him and he cried and cried and cried. If my cousin wasn’t dead I’d introduce you to him.

And I told him everything. “That was the reason why I used to lie to your girlfriends when they called on the phone ’cause I want you to stay home with me. I didn’t know why, but now I’m old enough to know why. You better be glad you didn’t get me pregnant. Mother woulda’ killed you.”

But I wasn’t on my menstruation or nothin’ like that. I was, you know, only seven or eight, but he was about fifteen.

He kept saying, “Please forgive me, please forgive me.”

I’m like, “I do. That’s why I’m lettin’ you know. But don’t you never do it again.”

They do that to girls, Jeff. Black mens . . . white mens too. Because white drunk mens always been on my body. Shit! You gotta pay me if you wanna do that.

Tina’s mother, meanwhile, cycled in and out of Northern California’s state psychiatric hospitals throughout Tina’s childhood. Sex for remuneration became Tina’s means to fulfill immediate practical survival needs and to seek minimal stability:

I used to sell my body just because I needed it and I was the type of person that was, you know, would give it up for money. If I didn’t say it I showed it. “You gonna do somethin’ for me?”

You wasn’t gettin’ my body if I wasn’t gettin’ nothing. You would have to buy me something to eat, and my cigarettes, my alcohol, my bus fare. Everything! Whatever I want I’m going to get. Everything. That’s when I had my sugar daddies . . . different mens that I would, you know, be with, you know, on their payday and stuff like that. They come pick me up. They would give me money—twenty or thirty dollars.

But . . . and then sometimes I mess with people that I didn’t know. But I ain’t never walked the street. Well . . . I walked the streets but not the whole stroll, you know. And then I would see people and, you know, they adored me. They wanted me. They would proposition me. Then. . . . “Yeah.”

Tina rejected the sex worker identity. She distinguished herself from “ho’s,” whom she defined as dependent on pimps. “I didn’t know that I was a prostitute. But then I knew I wasn’t no ho’ ’cause I wasn’t paying no man—no pimp.”

The child psychology literature documents a strong relationship between early sexual abuse and sex work in later life, implying that the logic for prostitution is based on violent disempowerment generated at the level of the individual within the traumatized psyche (Herman 1992). A theory of abuse, however, that engages the interface of psycho-affective turmoil with structural and institutional forces such as historically engrained inequalities around gender, class, ethnicity, family arrangements, and the provision of social services to vulnerable children is useful for understanding why it might feel empowering to Tina to make men pay for her body. “My body’s precious to me. I’m not going to give it up to nobody. And I a beautiful lady.” Arguably, by selling her body, Tina obtained a sense of control over the multiple sexual exploitations she was subjected to as a child (and continued to suffer later in her life).

Feminist anthropologists and philosophers have debated whether sex work can be considered a form of resistance to masculine domination in coercive contexts rather than being solely self-oppressive and objectifying (Pateman 1999; Wardlow 2004). Classical marxism and early Western feminism provocatively accused “bourgeois marriage” of being a legalized form of prostitution (Engels [1884] 1942; Goldman [1911] 1969; Wollstonecraft 1790). This interpretation is consistent with anthropological work on intimate sexual relationships in both nonmarket societies and industrializing urban settings that argues that sex work is not categorically distinguished from gift-giving or from marital economic dependence (see, for example, Mauss [1924] 1990:73; Tabet 1987; Wojcicki 2002; Zelizer 2005; see also Africa Today 2000).

After several months of ambivalence, Tina suddenly stopped “seeing” all her other “men friends” and declared her love for Carter. During their honeymoon weeks, they established a separate new camp all to themselves under another freeway overpass farther down the boulevard. Pursuing domestic stability despite their homelessness, they adopted a large black and brown dog and named him Freeway.

Carter is banging hard on a sheet of metal with a hammer, looking every bit the honorable laborer. Sweat stains his otherwise clean white t-shirt and brown denim overalls. He has a plaid lumberjack shirt tied around his waist and his baseball cap is turned backward. A half dozen brand-new metal street signs are piled next to him. He is banging at the center of a large NO PEDESTRIANS highway sign to form a crease in the metal. He presses his knee with the full weight of his body into the weakened spot and successfully bends the four-foot aluminum sheet in half.

Tina is sitting in a wicker chair in the middle of the camp looking like a pioneer farmer’s wife: cut-off jeans and a paisley cowgirl blouse tied in a knot at the belly button. She is peeling a potato; her feet are raised on a milk crate that she has covered with blue and gold chintz fabric.

She greets me warmly, springing up to give me a hug. “Stay for dinner, Jeff, with me and Carter,” she asks as she points to a bag of groceries provided by a Baptist Church food pantry. She explains that a friend she had treated to a beer on the corner yesterday brought it over this afternoon. I can see a quartered chicken, an onion, potatoes, frozen spinach (rapidly thawing), a stick of vegetable lard, and butter. Carter walks over, wiping his brow. “Yeah, Jeff, stay for dinner. I’ll cook up this chicken like you never had before. Just relax and take your pictures, we got it goin’ on.” He bends down and pecks Tina’s cheek.

Carter starts a fire in a large metal garbage can and jams several squashed street signs into the flames. He explains that he sells the aluminum signs to the recycling center as scrap. He has to blacken them first to hide the fact that he stole them from the Caltrans service yard ten blocks away. When the flames settle, Carter places a grill on top and throws on a skillet, adding lard and then the chicken, which he seasons with salt and pepper from a white porcelain coffee mug.

Tina washes the potatoes in a tin basin and dices the onions. “I love to chop, Jeff. Yeah, I love them knives. I went to culinary arts school to get me my A-1 chef license. My drug rehab program got me the job. I could use those knives! And never cut myself but I hated that cheese cutter. I loved to fix the salad bar. I never graduated because my instructor he act like he had a crush on me. He would give me a hug and shit and then his hands would . . . he’d try to feel on my butt.” Tina brings a large pan of water to boil on the fire and throws in the now fully thawed spinach. Carter asks Tina, as if he were proposing a cocktail, “Want a hit before dinner? Where’s the pipe?”

Tina energetically pulls apart piles of clothing before finally locating the crack pipe in the chest pocket of Carter’s blue jean jacket. Wagging her finger, she playfully scolds him for forgetting. She then jumps up and gives him a puff, pausing first to embrace him: stealing a kiss in the kitchen.

After the sun goes down, the flow of headlights on Edgewater Boulevard provides us with our only light for cooking. This does not faze Carter, however: “You can’t see in this darkness if the juices are clear, so instead I just listen for the sizzle. You don’t need to see to cook chicken; you can hear when it’s just right.”

Tina is back relaxing in her favorite chair, lighting a second hit of crack, her sandals kicked off and her feet up. She points to the freeway roaring above us and sighs, “Jeff, I’m tired. The cars are always going. The freeway never stops.”

Finally Carter announces, “Dinner is ready.” Tina grabs a jug of water for us to wash up. We take turns holding up a bathroom soap dispenser with Taco Bell stamped on the side. We are careful not to waste any of the water to avoid having to fetch more from the spigot at the farmers market half a mile away.

Tina sets the food out on a warped sheet of plywood balanced on top of a grocery store display case. Without fail, Carter always prays before eating, and after we sit down, he asks us to bow our heads in prayer. Once I saw Carter scold Tina for biting into her food without saying grace.

The chicken is delicious, and when I compliment Carter, he explains proudly that when he was in the army stationed in West Germany, he was appointed “number two chef.” He elaborately describes the ice carvings of swans he used to prepare “with a seafood bisque in the center, and fresh shrimp laid out around it. I’d put my all into that.”

For dessert, he announces, “Surprise!” and, smiling, pulls out an Entenmann’s cherry pie from under his chair. “I’m just sorry it’s not homemade.”

Carter’s older brother, Lionel, walks in unexpectedly. Carter offers him some food and introduces me, but Lionel is not interested. He is in need of a quick fix of heroin. Carter scrambles to find a syringe in the dark, and Lionel chides, “Hurry, the kids and my wife are in the car at the corner. I don’t have much time.”

As a special treat for his brother, Carter prepares a “speedball” by adding a pinch of crack to the heroin in the cooker along with a couple of drops of lemon juice to make the crack dissolve.

Tina warns, “Don’t use up all the crack.”

Carter snaps back, “Can’t we just enjoy this without your complaining?” The brothers proceed with their injections, and Lionel runs off immediately afterward.

I rise to leave and Tina hugs me. Carter accompanies me to my car out on the boulevard, struggling to find words to describe our pleasant evening: “Y’know, it was . . . it was . . . normal.”

During these early months of their relationship, Carter pursued the patriarchal fantasy of maintaining Tina “at home” while he went out to “hit licks [steal].” When we would run into him rushing around alone on the street, he would say affectionately and proudly, “I got to get my Tina well” or “I’m takin’ penitentiary chances for my girl.” Tina embraced this gendered division of labor and eagerly domesticated herself so long as her needs for crack and alcohol were fulfilled. She basked in the romantic outlaw masculinity of her “man.” On one occasion, Jeff visited their camp to find Tina affectionately admiring Carter, who was sound asleep with his head on her lap. She explained, “I got me some crack, but I don’t want to wake him up. No! I’m going to let him get his rest and smoke it all by myself because he do be tired. He and Sonny hit a lick last night. He was working hard.”

On another visit, Jeff found Tina watching television alone in the encampment, saddened by the overdose death of a friend named Long John. He had been an occasional burglary and scavenging partner of Carter, specializing in stripping recyclable metal and wooden beams from abandoned buildings and unguarded warehouses. Tina recalled:

They wouldn’t let me in the buildings, because Carter says, “This work is not for a woman.” So I just stand there as a lookout while the mens did all the heavy lifting. I don’t like that. So instead I stay here and watch TV. I make sure Carter get me the batteries for the TV and everything before he goes out to work.

Sometimes they be coming back with big old beams that need to be cleaned. ’Cause clean shit cost more. But I ain’t cleaning that old nasty wood. I’m like, “I want my crack, Daddy.” Besides, I be asleep when they come back with the wood. So they pay Al to take out the nails and scrape the beams. Al like to clean. And Long John, he likeded to sell it clean.

This particular conversation was interrupted by Carter running into the camp to ask Tina for a screwdriver. While she rummaged through the mounds of junk stacked around the camp, Carter grabbed a rusted trowel from the ground and ran off. He returned a few minutes later brandishing the broken-off corner of a license plate with a valid California registration sticker affixed.

Carter: I’m gonna get ten or fifteen dollars for this. I took it from this Chinese or Mexican dude or something. He’s the motherfucker I was telling you about, parked outside the McDonald’s. He had a big ol’ soda sitting on the roof of his car, and I seen that he wasn’t drinking it no more. So I ask him if I can have the rest of it.

But he picks up the fuckin’ soda, takes a sip out of it, and throws the whole fucking thing down on the ground. Then he jumps in the truck, right, looks at me, laughs, and drives by. Pointing at me and shit, like I’m a fuckin’ sideshow or clown or something.

So I peeled his ass for the sticker on his plate when he happened to park in just the right spot. [holding up the trowel] This worked perfectly, steady, strong, and flat on one end. It fits in the groove of both a flat screw and a Phillips screw. How long was I gone, less than a minute? Thirty seconds for one screw, twenty-eight for the other.

Tina: [hugging Carter] My man’s a tiptoe burglar. . . . He so bold!

Carter: Plus DMV [Department of Motor Vehicles] is closed now until Monday. That man going to have to take off a whole day of work to go get him another plate.

Tina: [sighing] I gotta go back out to get me some more bottles and cans, get a few dollars and pick up some crack.

Carter: [kissing Tina on the forehead] No you don’t, Momma. We’ll get by. I’ll handle it. I know you tired and want to rest.

Tina: [resting her head on his shoulder] Mmm-hmmm.

Tina’s homeless version of the homebound bourgeois housewife did not endure. She increasingly took on the active role of outlaw running partner, joining Carter on his burglaries and in his instrumental bullying of the whites. This deepened their romance and was more consistent with Tina’s habitus forged in a childhood of intermittent nurture and abuse by outlaw kin and neighbors. Carter and Tina publicly celebrated their commitment to one another as a couple through public displays of aggression against anyone who wronged them. They enjoyed, for example, telling the story of “whooping Frank’s motherfuckin’ white ass” after he double-crossed them on what they called “our cobblestone lick.” On one of their nighttime forays Carter had “cased out” the city of San Francisco’s underground storage site for cobblestones.

Carter: I’m talking about thousands and thousands of cultured cobblestones. The fabricated kind that they use to beautify houses, right, for false fronts that increase the value about twenty, twenty-five thousand dollars just on that look alone.

Frank, who was painting a sign for Sammy, the owner of the Crow’s Nest liquor store, brokered a deal. Sammy was renovating his home and offered to buy one hundred cobblestones at fifty cents each. When Carter and Tina delivered the heavy shipment, however, Sammy insisted on dropping the price by half because Frank had explained to him the difference between “cultured concrete cobblestones” and genuine, old-fashioned ones.

Carter: We carried a hundred motherfucking stones up a fifty-foot-high hill from where the city stores them.

Tina: And had to take them over a chain fence, too, that got barbed wire on it. [inhaling crack and handing Carter the pipe]

Carter: At first I thought, I can’t use Tina for this job, ’cause she short-winded, and I can’t have her going over that high fence. The stones are heavy and her arms are just gonna turn to mush. [inhaling crack]

But Tina did great. That skinny frame of Tina’s could work faster than any man’s . . . better than Sonny and Al put together.

Tina: [grabbing the crack pipe from Carter] And one of them cobblestones fell on my damn leg. So when we saw Frank this morning, I was like bam! [throwing a slow-motion punch] Carter tells me, “I didn’t know you was good with your left.”

I said, “Shit! I’m good with both of ’em.” And Frank said he wasn’t gonna hit no girl. But I said, “Motherfucker! I ain’t no girl! I’m a damn woman. Hit me.” [laughing and swinging another punch] Bam!

Even Carter don’t like to fight me. [inhaling crack]

Philippe: How did you learn to fight?

Tina: My sister made me fight when I was a kid going to school ’cause people used to pick on me and I didn’t hit back. And she told me, “If you don’t hit back, I’m gonna kick your ass.”

She said [raising her voice], “Now hit her! Hit her in the jaw! [shouting] Hit her in the mouth!”

But I tell her [meek voice], “I don’t like hurting people.”

[threatening voice] “You better! Because ah’m’a whoop your ass my own damn self if you don’t.”

Philippe: How old were you?

Tina: I was eight years, and I didn’t want my sister to kick my ass.

She said [angry voice], “Now stomp that bitch! Stomp that bitch! She tryin’ to hurt you. Stomp her, I said!” [inhaling more crack and going silent]

Carter and Tina’s next victim was an acquaintance nicknamed Bugs, who occasionally parlayed drug sales for Carter. On one of their deals Bugs ran off with two hundred dollars in cash that a contact had fronted Carter to buy powder cocaine, a high-end product that was difficult to find on the street in the 1990s and 2000s, in contrast to crack, which was easily accessible in homeless venues.

Carter: Bugs was sick this particular day, which I can understand that. When a dopefiend is sick, a dopefiend is sick! He do what he gotta do. But I had told him that I was gonna fix him that day, and I’m a man of my word. And there’s certain things that you do, and certain shit that you don’t do. And that was definitely a no-no on something that he shouldn’t of did. He was the goddamn perpetrator instead of the dopesick victim.

Tina: [handing Carter a half-full bottle of Cisco] So when we saw him the next day, Carter knocked him out on the first punch. . . . Knocked him smooth out.

Carter: Well, yeah, but he woke up, and was attempting to try to stand up, but he was taking too long, so I snatched him up and knocked him down again.

Tina: After Carter knocked him down I was just stompin’ him in his chest.

Carter: And we commenced to moppin’ the concrete with his ass.

Tina: But the lady at the florist shop came running out talkin’ about [shrill voice], “Just take that mess somewhere else.” I was stompin’ him in his chest. I had on them loafers with the two-inch heels and they leather ones, you know, the old-fashioned ones. The ones that tie up.

Carter: Tina had on some hard-toed shoes. Kickin’ him in the back, and then the head and then the neck.

Tina: Stompin’ him! His face was bloody red. And Sonny came tellin’ us, “No! No! Stop that!”

I pushed Sonny back, “Sonny, you stay out of it. This motherfucker almost got us killed.” But anyway we took off ’cause the police, the ambulance, and the fire truck came. [inhaling crack]

Carter: It was a spectacle . . . like a parachuter landing in the middle of Market Street at lunch time on a Wednesday.

Tina: [handing Carter the crack pipe and putting her two hands gently on both his cheeks] Thank you, Lord, for bringing us together. I’m Carter’s partner his friend his lover his woman his fiancée—everything!

Carter: Tell it! [inhaling crack]

Tina: We don’t need nobody in our way ’cause they ain’t gonna do for us like we do for each other.

As an ironic closure to this expression of affection, Tina suddenly pulled back from Carter’s embrace with a pained expression. She patted his jacket pocket and exclaimed, “You been carrying another Cisco on you all this time? Gimme some of it!” Sheepishly, Carter unzipped his down parka and handed her a brown paper bag. She yanked the bottle of Cisco out of the bag, held it up to the sunlight to reveal only a half inch of the pink fortified wine, and shook her head.

Tina: Ain’t that a shame! Didn’t even save me none. I never do you like that.

Carter: Don’t be yelling at me. Muscle mouth!

Tina: [waving the empty bottle at Carter] I’m not your motherfuckin’ fool, ignorant son of a bitch!

The outburst ended with Carter backing down: “Okay! Excuse me, I ain’t saying nothin’ else. I apologize if I said anything wrong. . . . I apologize. . . . [yelling and raising his hand threateningly] I said I apologize!” Tina smashed the bottle on the ground and clucked mockingly, “Tsk, tsk, tsk.” Interpersonal flare-ups like this one between otherwise affectionate running partners and lovers reminded us that in gray zones, aggression is the most effective means of asserting rights. Violence is normalized as ethical. In Tina and Carter’s case, violence also deepened their romantic bond. Following the same interpersonal gray zone logic, within a few months of his brutal beatdown, Bugs once again was periodically hitting licks with Carter and Tina and he sometimes slept over in their camp.

One evening, Jeff ran into Tina and Carter in a laundromat in the residential neighborhood up the hill from Edgewater Boulevard and offered them a ride to their camp. While Jeff was helping them load three garbage bags full of still warm laundry into the trunk of his car, a young bohemian-style white man dressed only in an undershirt and shorts (clearly down to his last set of clean clothes) began asking everyone in the laundromat, exasperated, if they had seen what happened to his clothing: “All of my laundry is gone. Everything I own. I can’t believe this! I don’t have any more clothes.”

Jeff turned to Carter and whispered out of earshot, “Did you guys take ’em?” Tina responded so indignantly to the accusation that Jeff felt a little embarrassed at having suspected them: “C’mon, Jeff! We don’t want his clothing.”

Ten minutes later in a back alley off Edgewater Boulevard where they were unloading the overflowing laundry bags into Tina and Carter’s shopping cart, a set of headlights on high beam blinded them. The same young man from the laundromat, still in his shorts, jumped out of his car pleading earnestly, “Please! I don’t want any trouble.” Shivering in the damp fog, he placed his hands on Carter’s shoulders and pleaded again, “I just want my clothes back.”

Carter pushed him away, shouting, “We don’t have your damn clothing!”

The young man did not back down. He yanked a blanket out of the shopping cart, exclaiming, “This is my comforter!”

Carter protested loudly, “No it’s not; it’s mine.”

The young man continued: “And this is my t-shirt; my girlfriend gave it to me. I can tell you the history of every piece of clothing in this pile!” He turned to Jeff, who was taking pictures: “What’s going on here? Is this art?”

Carter suddenly slapped his forehead and changed his tone of voice: “Oh, wow, we must’ve grabbed your stuff by accident.”

Also suddenly shifting to a friendly tone of voice, Tina chimed in: “Oh, my! How ridiculous! Isn’t that funny? . . .” Then she whispered angrily to Jeff, “Motherfuckin’ Carter stealin’ other people’s shit like that!”

Surprised at having been so blatantly double-crossed by Tina and Carter, Jeff stopped offering them rides for several months and began visiting the scene only on foot. Several years later Tina recalled the lick and apologized for it belatedly but sincerely. She and Jeff shared a laugh, remembering this awkward early incident when he and Philippe were still learning the limits of trust and the serendipities of petty crime among the homeless.

A few weeks after the “laundry lick,” Carter, sitting despondently, refused to acknowledge Jeff’s greeting when he arrived early one morning. Tina pulled Jeff aside and whispered, “His little sister, Priscilla. She died.” Carter sullenly prepared a large injection and immediately collapsed forward after hitting a large vein in his triceps. Panicking at this full-blown overdose, Jeff shouted in Carter’s face while Tina slapped Carter’s cheeks repeatedly. It took a full thirty seconds for Carter to flutter his eyes slowly. He then immediately jumped to his feet and stomped out of the camp without saying a word, leaving Tina calling after him, “You motherfucker! You scared us to death.” On several other occasions when Carter was upset, he overdosed in a similar manner. Each time we were unsure whether it was a histrionic display for our benefit or an accidental near-death.

Carter was arrested at the Discount Grocery Outlet two hours after this particular overdose. He had slipped two five-pound sticks of salami down his pant legs, intending to bring the dried meat to his sister’s wake. He punched the security guards when they stopped him. Tina, who had been waiting outside the store, cursed the police officers as they pushed Carter into the squad car. A member of the ethnographic team restrained her, and she strategically calmed herself down just in time. “I love Carter, but I’m not gettin’ busted for no man, and Carter is on a tear. He don’t give a fuck if he gets busted. I need to take care of myself.”

Despite the assault and theft charge, Carter was released from jail “on his own recognizance” to attend his sister’s funeral. Tina accompanied him. It was their first public appearance among Carter’s extended family as a couple, and they were welcomed warmly. They began to go regularly to Carter’s family reunions on holidays. Sometimes they stayed overnight at an “auntie’s” home. They invariably returned from these events refreshed, with newly laundered clothes and overflowing containers of leftover food to share.

That Christmas, Carter and Tina spent a full week in the home of Carter’s eldest sister, Beverly, the same household from which Carter had been evicted when we first met him. Tina was thrilled. “We had our own room . . . the guest room, all to ourselves.”

Integration into Carter’s kinship network, however, did not alter their outlaw lifestyle.

Tina: Our Christmas was beautiful. We gave everybody the same thing. Socks, ten pair in each bag. They were so happy.

Carter: See, Jeff, they was stacking, boxes and boxes and boxes, outside a store on Mission Street. And they got a person walking back and forth to watch the stuff. But a customer came up asking him something so he turned his back to the street for a moment. So I just picked up the biggest box. Walked to the corner and waited for the green light and just walked on.

Tina: Like it was the thing to do!

Carter: We had a hundred fifty pair. White thick socks. Ten pair in each bag.

Tina: And we didn’t know what we was going to do for Christmas without no presents.

Carter’s deceased sister, Priscilla, had been sick with AIDS for several years, and her family had allowed her to spend her final years in the home where she had grown up along with Carter and her seven other siblings. It was located exactly eight blocks up the hill from Edgewater Boulevard on the same block where Felix’s aging mother still lived. Carter took Jeff to photograph the house before its sale shortly after Priscilla’s death. Carter climbed onto the balcony, pointing out the city’s pro football stadium, and reminisced about how everyone on the block would run out of their houses to celebrate touchdowns during Super Bowls, “with the roar of the crowd booming from the stadium.”

Carter’s share of the profits from the sale of his childhood home amounted to six thousand dollars, once the lawyers, liens, and outstanding taxes were paid. Carter and Tina’s lives immediately improved, but strictly within the limits of their existence on the street.

Tina: Carter got money in the bank. Six in cash! He haven’t messed with it. He been turnin’ it over and turnin’ it over. Keep it goin’, buying dope and selling it and shit. But you can only go for so long when you’re dippin’ in it. Carter, he gonna get us a camper, and he say that he need clean clothes to get a start on that to go pick it out. So now we is washing up these clothes [pointing to a lime green polyester pantsuit drying on a clothesline stretched between their shopping cart and the chain-link fence].

Yesterday Al came with us van shopping in South San Francisco. That’s where his parents live. But the man selling, he act like he was prejudice’ and we didn’t buy nothin’. We made a couple more stops, but where Al took us, it was very very very expensive. Like rich black people, you know. When Carter told them we had two thousand dollars to spend and that he got cashier’s checks with him and everything, they just go like [frowning and looking down her nose] . . .

A week later, Tina and Carter were the proud owners of a fifteen-year-old orange and white Chinook camper. They christened it Betsy and embarked on a second honeymoon, unabashedly hugging, kissing, and crooning their pet names—“Momma” and “Daddy”—to one another during our visits. They remained “in pocket” without having to scavenge or steal for another entire month.

Tina: I haven’t been wanting for nothin’. He been giving me money every day. I don’t be broke and I don’t have to ask. He automatically know his woman ain’t got no money in her pocket and he know how much better I feel with money in my pocket. Even if it is only a couple dollars.

They parked their camper in an alley behind the McDonald’s in order to use the restrooms more conveniently, and they began bathing every morning in the sinks. After their second ticket from the police, Carter and Tina moved their camper five blocks deeper into the warehouse district to a less conspicuous side street amid disabled big-rig trucks and garbage-strewn empty lots. Al and Sonny parked their pickup and camper-shell next to them. Sal, the dealer, also moved his sales spot onto this same side street using the Chinook to block his visibility. Carter was outraged, relishing the opportunity to display a “not-in-my-backyard” homeowner role, complete with the patriarchal detail of protecting his woman from scum:

They be ten motherfuckers back there buyin’ dope, and I got to be hollering, “Ex-cu-use me! Wait, wait, wait, wait. This ain’t gonna work. You all gotta motherfuckin’ disperse.”

I know they didn’t feel good, and they is just trying to cop [buy heroin], but I had asked them before nicely, and they transact right on that little bench that Sal done set up behind my camper. And I got too much to lose. I got my woman in here [patting the side of the camper].

Plus, half of them come on bikes or pushin’ a buggy. They ain’t got no vehicle that’s registered or no license or nothin’ to lose like me. And this here is my roof, my home, my transportation, and everything else. Everything I own is here, and I ain’t gonna let these mother-fuckers jeopardize me or get me my shit took. Who is gonna help me get it out of impound? Not a damn one of them.

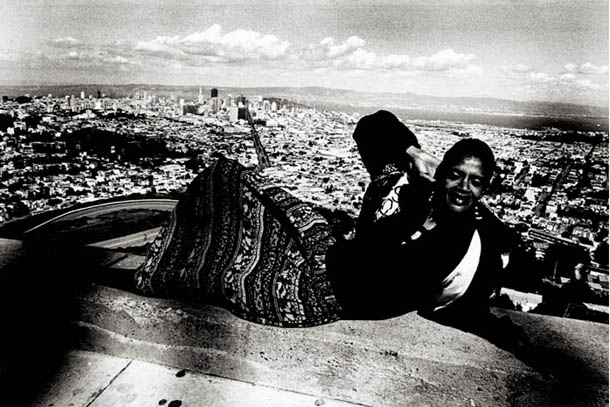

Tina basked in the stability offered by the Chinook. On Mother’s Day, she asked Jeff to take a portrait of her at Twin Peaks, San Francisco’s most spectacular tourist vista point. She missed her mother and wanted to send her the picture as a gift. In preparation for posing, Tina washed her hair, pouring water from an empty Cisco bottle while leaning out the passenger side of the camper. She then dressed up for the occasion, putting a denim vest over a long-sleeve, décolleté silk blouse tucked into an ankle-length batik print skirt. She also wore her favorite black patent leather lace-up shoes with black stockings and applied black eyeliner along with her usual cherry red lipstick. Before hopping into Jeff’s car she grabbed a purple chiffon scarf, a brightly patterned silk jacket, and crystal earrings. Al was washing his dishes off the back of his pickup, using a Chinese wok as a wash basin, and Tina offered him a ride. He had a box of records to sell and there was a vintage vinyl store in the upscale Castro neighborhood located on the way to Twin Peaks. In his dirty t-shirt, paint-splattered blue jeans, work boots, and battered baseball cap, Al offered a dramatic contrast to Tina, but he eagerly jumped into the car.

While waiting for Al to come out of the record store, Tina grabbed a few grapes from the display of a boutique-style produce market. The owner burst out the door, yelling in English with a strong Arabic accent, “This is the second time I’ve caught you stealing my grapes! If you do it again, I will call the police. Don’t touch my goddamn grapes.” Tina snapped back, “I’m only tasting your goddamn grapes. And I’ve never even been here before.”

Al, still in possession of his heavy box of records, came out of the used record shop disappointed. He caught the end of the conversation and ran up behind the fruit seller, threatening, “You need to be careful who you’re talking to like that. We’ve never been here before.”

The storeowner was not intimidated and irately raised the ante: “What are you going to do about it?” Al retorted, “No! what are you going to do about it, you goddamn foreigner?” At the time, AM talk radio hosts in California were promoting a right-wing ballot initiative to deny health care, education, and welfare benefits to undocumented immigrants, and Al had fully imbibed their xenophobic arguments. The two men shouted heatedly at one another for a good two minutes, leaving Tina standing silently to the side. Sticking their fingers into one another’s faces, it appeared they were about to escalate to punches. Finally the store-owner spun around and retreated inside his store with a dismissive, “I’m sick of you fucking homeless. Fuck you, homeless!”

“Can you believe that!” Al fumed. “He called us homeless. How did he know we were homeless?”

“I didn’t hear him say that,” Tina giggled innocently, barely holding back an outburst of hilarity. She then draped her arm over Al’s shoulder and doubled over, gasping between outbursts of laughter, “Al, your teeth slipped out.”

Al frowned, trying to remain angry. “And it’s a good thing he didn’t laugh at me losing my teeth or I would have decked him.” He smiled, however, despite himself and snapped out of his rage: “Come on! Let’s go try and sell these records somewhere else.”

Back in Jeff’s car, Tina looked into the rearview mirror and took out her makeup kit. No longer smiling, she whispered to no one in particular, “Homeless?” and then sighed resignedly, “Oh, well, homeless.”

The Chinook camper allowed Tina and Carter to expand the reach of their burglaries. Formerly, they had been limited by their reliance on shopping carts to transport their scavenged and stolen goods. With the mobility, storage capacity, and camouflage of the camper, hitting licks became more profitable than recycling. With their home conveniently omnipresent and mobile, they seamlessly wove drugs, alcohol, and income generation into the cadence of their romantic domesticity. They no longer had to leave one another’s side.

Carter considered himself to be a skilled entrepreneur who carefully weighed cost, benefit, and risk. For that reason he began specializing in “hitting” what he called “wood licks.” Opportunities were plentiful during these years because of the spike in San Francisco housing values, fueled by the dot-com boom. In the 1990s, the median price of a three-bedroom home in San Francisco rose an unprecedented 80 percent, and rents more than doubled (San Francisco Board of Supervisors 2002:66, 68).

Carter: They got a lot of brand-new full six-unit complexes going up all over the city. The further west you go out toward the beach, the more stuff they leave out. You’ll see stacks of this ’n’ that laid out on the sidewalk. Ain’t nobody figure it’s gonna be took in those neighborhoods. And you pull up, dim your lights, load up ten or fifteen sheets of plywood, and go on about your business. [snapping his fingers] That quick. You know, be quiet be quick and be gone.

Some of them are one-time licks, but then it depends on how you leave it, you know. If you don’t be real greedy, right, and only get a few at a time then you’re all right. That’s what I been doing. I get four from this stack, six from that stack, and four from that one, right, and then go on about my business.

But puttin’ the wood up here [patting the roof of the camper] makes the camper top-heavy, and the clutch is winding out. I gotta get me a little pickup truck. Last week, we had two twenty-foot four-by-sixes . . . motherfuckin’ whole house foundations! We was on full carryin’ them. I couldn’t believe it!

I found a client. Got paid. And fixed real goddamn good. Wasn’t feelin’ no pain. No pain. No pain. [pointing to a passing BMW] Oh that’s nice, boy! Shiny!

I’m so proud of my girl. You should have seen how fast she worked last night. The cops had pulled around right when we were loading Betsy. We froze with the plywood sheets in our hands, and as soon as they passed we jammed them fast!

A few weeks after this conversation, Carter purchased a badly dented, orange 1970s Chevy Luv public works truck that had been retired from service by the city at a public auction. Tina named it Suzie-Q. They used it exclusively for hitting licks and maintained Betsy, the Chinook camper, inconspicuously parked in the back alley near the salvage yards. It looked like merely one more abandoned vehicle waiting to be stripped.

Tina apologizes for the condition of the camper. “I was planning on cleaning it last night, but we were out on a lick and you know how it goes.” Carter, dressed in a black sweatsuit made of parachute material also apologizes, but not for his role in the disarray. He is referring solely to Tina’s negligence as the female homemaker. I push aside a pile of clothes and squeeze inside. Carter jokes that they have accumulated so much stuff for resale that they no longer have enough room to sleep side by side.

Carter finishes fixing and falls into one of his deep, post-injection nods, emitting periodic moans of pleasure to reassure us he has not overdosed.

A faint sound of buzzing snaps Carter to attention. He pulls out a vibrating beeper clipped to his waist and squints to read the message, announcing, “Awright, we gotta go!”

Smiling at my surprise, he explains: “My client, the contractor I was tellin’ you about, gave me this beeper so’s to contact me for special orders. He goes window shoppin’ at the used lumberyard to get the prices, and I give him at least forty percent off on anything and everything that he orders. He ends up savin’ a bundle.”

Tina: “Yeah! How long you been working for him now? A couple months?”

Carter: “No! I never work for him. I been dealin’ with him. I ain’t working for the bastard. I work for myself. So, it’s just like . . .”

Tina: “ . . . a job. He always comes to you.”

Carter: “Everybody’s always wanting to run their own business. Basically that’s what I’m doing. Workin’ my ass off, believe it or not, but that’s enjoyable ’cause it’s on my own time—talking to people; goin’ to companies; sayin’ hey, man . . .

All three of us squeeze into the front seat of Suzie-Q and Carter drives rapidly to the lumberyard. Moments later, a brand-new white pickup truck parks in front of us. An older Latino man wearing a baseball cap, a down vest, and a tape measure on his belt exits from the driver side. Carter jumps out to greet him, returning moments later with a big smile. He winks at Tina, “It’s the lick I was telling you about.”

We drive twenty minutes to a residential neighborhood and park under a shady tree across from a middle school. Carter and Tina each don road crew reflector vests, slipping them slowly over their clothing. I have never seen them move so slowly and deliberately on a lick and am confused. It is five o’clock and broad daylight. What can they be planning? There are no stacks of construction supplies in sight, nor any shipping containers or warehouses in the vicinity. They walk over to a series of traffic cones signaling a road repair trench, which is temporarily covered by thick sheets of plywood to accommodate the rush hour traffic.

Nonchalantly, they rearrange the barricades and cones, waving the commuter traffic to pass. Still moving slowly, they lift the large sheets of plywood one by one into the back of Suzie-Q. Tina flashes me a quick smile before lapsing into the bored, disengaged expression of a public works employee earning overtime pay.

They rearrange the cones to block the now-exposed trench and calmly climb back into the pickup, where they seal the success of the lick with a kiss before driving slowly back to Edgewater Boulevard.

We began hearing rumors that Tina had started injecting heroin. Both Carter and Tina denied it, but everyone suspected it. Sonny, who was Al’s running partner during this period but who also occasionally burgled with Carter and Tina, was especially worried. He considered heroin injection inappropriate behavior “for a lady.” Sonny expressed his concern for Tina’s welfare in an old-fashioned patriarchal trope, but he also had a self-interest. Currently, Tina shared crack with both Carter and him without requiring reciprocal gifts of heroin. If she developed a physical dependence on heroin, resources would be drained from this microbalance in the local moral economy of sharing that currently favored both him and Carter. The subtle mechanisms of symbolic violence around appropriate gender roles probably made Sonny oblivious to his manipulative self-interest. He thought of himself as someone who genuinely cared for both Tina and Carter and celebrated their romantic dream. He was only too familiar with the interpersonal betrayals that accompany heroin addiction in extreme poverty:

Bof’ of them hooked, that’s a fucked-up thing! It’s hard enough tryin’ to do this here [rubbing the injection scars on his arm] by yourself, but it’s gonna be doubly hard if they doin’ it together. Trying to take care of two people. [shaking his head] It don’t work. Every time he have something, she got to have some of it too. Even a wake-up in the morning and shit. ’Cause now when he’s sick, she’s sick.

If he goes out while she asleep or something to do a sack [bag of heroin] by hisself and get well while she stay back at the camper and wake up sick . . . [shaking his head] He’ll come back without tryin’ to let her know that he had made a hustle and got some money and heroin. And then she gonna get some and she ain’t gonna wanna split it either. “Oh, you motherfucker, why you didn’t save me none!”

Or they be tryin’ to do each other like how you add a little water on the sneak-tip to the cooker to make your partner think he’s gettin’ his fair share.

It leaves her goin’ out there in the streets to find someone who might have some dope. And whatever else it might lead a woman to do. . . . She a lot weaker than a man. Damn! Lay on your back just to get some dope. You know what I’m sayin’? Lay on your back to get ten dollars to get one fix. Then you gotta think about tomorrow, the next day, or even just later on that day.

And the thing is, Carter care about the girl a whole lot, too, you know, and I think she probably genuinely cares about him a lot, too, but their relationship is a odd-couple thing.

I warned them they gotta try to find some kinda common ground and come to some kinda conclusion or solution. If she gets hooked on heroin it’s gonna take bof’ of them to hustle. I don’t want to see a girl out there, turnin’ no dates and stuff like this here man. Because she put herself in danger. You don’t know who might pick her up—some wacko or somethin’. Then you goin’ to the hospital because they done beat you up, took your money, and shit. It’s sad. Really sad.

Man! I sure am glad I don’t have no girl.

Tina chose a Thanksgiving cookout at the white encampment, organized by members of the ethnographic team, to confess her public secret. Guiding Jeff aside gently by the crux of his elbow, she whispered, “I have something I need to tell you. I’ve started shooting. I can’t talk now, but I didn’t want to hide it from you no longer. We’ll talk later.”