It would kill my mother to see me like this.—Felix

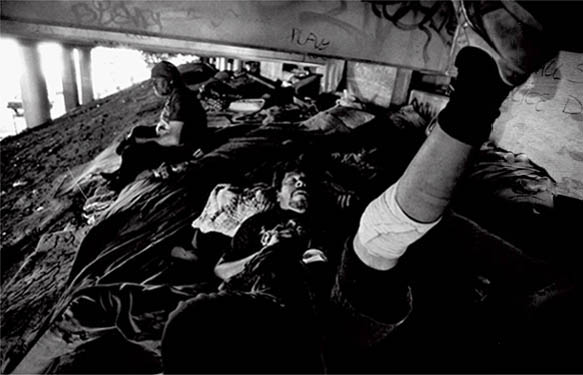

With only a few exceptions, all of the Edgewater homeless grew up poor. Most of their childhood homes were violent, and many had alcoholic parents. A few, however, described their families as having been stable and supportive.

There were notable differences across ethnicities in how families coped with having one of their adult members living as a homeless drug user. The majority of the whites had no contact with their natal families; many no longer knew where their parents and siblings lived. Al and Ben were the only whites in the core network who kept in touch with their parents. Three others (Frank, Hogan, and Petey) recontacted their families temporarily during the years we knew them, but only in very exceptional circumstances such as when they were hospitalized for life-threatening conditions or when they agreed to introduce us to a family member to conduct family history interviews. In contrast, all the African-Americans maintained ongoing relationships with their families and with extended networks of kin. Several (Reggie, Stretch, and Vernon) lived with aunts or spouses. Two of the three Latinos in our core group, Felix and Victor, lived intermittently with their mothers. Periodically, they would be thrown out for stealing or for selling drugs at home, but eventually, sometimes within a few months, other times a few years, their mothers invited them home again.

It was difficult for us to elicit stories of childhood and family from the whites. Their outcast status within their families was a source of shame that reverberated with their generalized sense of failure and depression. On major family-centered holidays, however, they often came together as a group and reminisced about their childhoods. During our second Christmas on Edgewater Boulevard, Nickie baked a ham that had been given to her by a volunteer outreach worker at San Francisco’s Women’s Needle Exchange and brought it to the main white encampment. Her eleven-year-old son was spending the day with his father, now a recovered addict married to a prison guard and living in the suburbs, and Nickie did not want to spend Christmas Day alone in her apartment in the projects. While we were eating Nickie’s ham in the camp, an elderly couple we had never seen before drove up and unloaded a case of beer from the trunk of their car, calling out a cheerful “Merry Christmas.” This serendipitous holiday gift from housed strangers unleashed a slew of childhood Christmas stories:

Felix: I used to like Christmas morning. All night we’d try to sneak into the living room and take a peek at the presents. Just rip a little corner of the wrapping paper.

Frank: When I was a kid living in the projects I used to dream about getting a bike. It seemed like all my friends had bicycles, nice bikes. And I didn’t have a bike. I had these vivid dreams that I got a bike on Christmas, and I’d wake up in the morning and it’d be so real that I’d be looking around for my bike. Then I’d realize that it was just a dream. And I’d be disappointed. [laughs]

Hogan: I always wanted a bike.

Nickie: [waking up from a deep heroin nod] I got a Barbie doll once for Christmas.

Max: I had the flu one Christmas. And I got a bicycle that year. My first one. [smiling] They gave it to me Christmas Eve, ’cause I wasn’t feelin’ real good. It was a beautiful bike, beautiful bike. I sat on it, and it made me feel better. I remember, man, an expensive bike. . . .

Frank: Never got a bike when I was a kid.

Hogan: Nope. Me neither. Not for Christmas.

Max: I was really lucky. That bike was the best thing I could ever have got. . . .

Hogan: I wanted a bike.

Felix: Oh, fuck! What kid didn’t want one, man? I never got a bike for Christmas. . . .

Max: I stripped my bike all down. Took the fenders off. [softly] My father blew it when I did that. . . . [all speaking simultaneously]

Hogan: At that time my parents didn’t have no money. . . .

Frank: My parents never had any money. . . .

Max: It was one of those old Schwinns [smiling], with the horn in the middle—beep! And it had a spring in the front, had one hand brake and foot brakes. It was a special-made bike, I guess. My father was in business—he had a bar in North Beach—and he was doing well, so I had a nice bike. . . .

Hogan: [taking his sneakers off] Shit! I got a hole in this sock.

Max: Once you get a little hole in ’em, that’s it!

Hogan: I always wanted a new bike for Christmas.

Unlike the whites, the African-Americans often spent major religious and civic holidays (Christmas, Thanksgiving, Memorial Day, Fourth of July, Easter) with their families. Sonny had an especially warm relationship with his family, and he was fully integrated into all their reunions, including funerals, birthdays, and marriages. He spoke about his mother with affection:

She is one of them old French Creole girls with Indian in her. But I never tripped on that, because she’s just an old black woman that I love. But my daddy, he was an old dark-skinned guy, and I used to tease her [giggling], “Momma, what you see in this old black man?”

Sonny’s mother had migrated to San Francisco from New Orleans when she was pregnant with him. For the next thirty years, she worked as a registered nurse in private homes. According to Sonny, “All her patients were millionaire folks, you know, like the Swanson family, who make the Swanson pies. They stay in some mansion right there in Pacific Heights.”

Sonny’s father was also of French Creole descent, from rural Lafayette Parish in the bayou, where he ran juke joints. Sonny described him as “a player who drank.” He was proud, however, that his father “maintained his home.” Sonny described with emotion his father’s death in old age:

We had the whole family there spending nights. It was a gang of us. I’ll never forget it. I was in the ICU with him alone, rubbing his head, sayin’, “Daddy, I love you.” And I’m crying. Then for about ten seconds, he opened his eyes and looked at me. I started cryin’ real hard and callin’ my mom. She came in and sat down next to him. It was like my dad was waiting for her, because he passed right after she came in.

The affection and concern of Sonny’s mother for her wayward son were poignantly reflected in a tape-recording made by one of the members of the ethnographic team when Sonny called her from a pay phone. The sun had just set and Sonny was supposed to be spending the evening at her house. He had managed to sell a scavenged electronic keyboard for twenty dollars, however, and he now wanted to buy crack.

Sonny: [dialing] I wanna make sure to call so she don’t think I don’t care. . . .

Hello, Ma? I’m not gonna be comin’ home tonight. . . .

Yeah. . . . Uh-huh. . . . I got a couple of blankets and stuff. . . .

Oh, I had lunch. . . .

Well, mmm-hmm, you know . . . I’m not eating no hot meals or nothing like that. . . . Whenever I can, but . . . mmm-hmm. Well, yeah, I eat enough to keep going. A lot of junk food and stuff, but . . .

Yeah, do I! [laughing] That seem like the main course, hamburgers, cheeseburgers. . . . No . . . I haven’t had no Chinese food in a while. . . . Uh-huh. . . . Yeah. Yeah—

[long pause] Well . . . mmm-hmm, I will see what I’m gonna do tomorrow Ma, you know, about getting on this methadone and stuff like that.

Mmm-hmmm, yeah. I’m trying my best. . . . Yeah, to uh, bring myself down to the program. . . .

Yeah . . . mmm-hmm, like the doctor told me. . . . Mmm-hmm . . .

[softly] Yeah. Uh-huh. Yeah. ’Cause you keep askin’ me. . . . Yeah . . .

I love you too, Ma.

Even though Sonny failed to fulfill his mother’s request that he enter a methadone program, she continued to welcome him home. He was her first-born, cherished son. When her second husband died of smoke asphyxiation in an electrical fire in her home halfway through our fieldwork, Sonny sat next to his mother at the funeral service and comforted her throughout the ceremony, his arm around her shoulders.

Sonny was the only one of his siblings involved in drugs and crime, and he referred to himself as the “black sheep” of his family. His extended family had been part of the large-scale African-American migration from the rural Deep South to the urban Bay Area during World War II. The family members had, for the most part, been successful. Sonny had three sisters and two brothers. One brother was a bus driver, and the other was a roofer, who also helped his wife run a beauty shop. Sonny’s oldest sister, born in New Orleans, worked at the San Francisco Public Library. He described her as “the head . . . head supervisor or something like that. She’s been there since she was like outta high school—thirty years.” His middle sister worked in a bank, and his youngest sister was employed in the San Francisco sheriff’s office.

Sonny relished his mother’s care and the comforts of her home. He was also proud of the achievements of his extended family. Nonetheless, hustling for drugs remained his number one priority:

I spent the weekend at my Mom’s ’cause it was my niece’s wedding—my baby brother Gregory’s onliest daughter, with his grandkids participating. And I’m glad I got to see my nephew, Richard Jourdan Jr., before he leaves for Germany. He gonna play professional basketball over there. He’s taking his whole family with him. He graduated from Balboa High School and got a scholarship to Cal Fullerton. They used to write him up in the papers. He played with the Warriors and the Hornets.

My niece looked beautiful, man. She had a very, very nice wedding. Bride, groom, and all this stuff. She and her man workin’ together in the airport. They be having a little janitorial service now for the last eight, nine months. At first, when my Momma invited me, I told her I didn’t have no clothes. She said, “Don’t even worry about that. We gonna help you get some all new stuff.” She didn’t want me bringing no shit in her house, no telling what’s in my clothes—you know, ticks, lices or something, or little bug eggs in the pockets. I took off all my clothes down in the basement and put it all in a big bag.

And I got into that bathtub . . . ooooh! Lord have mercy, that water turned dirty! But it was so relaxing. Then I let the water out, turned on the shower, and scrubbed down the rings of dirt to where there weren’t too much of no more dark black water. Then I ran the tub water again and sat down in there. And man! Talk about dope giving you that good feeling. . . . That water was so relaxing. I went off in some nods in there. Yeah, man.

After all that, Momma got the bed ready. Fresh blankets. Sheets. Turned on the TV with the remote control.

And then I went in the kitchen to get something to eat. She didn’t have too much to eat, you know, since she be there by herself mostly. She don’t be needing a whole bunch of food, but she had cooked some greens the day before. No, I take that back, it was cabbage.

She said, “Hey, baby, I got some cabbage in there if you want, and some rice.”

I said, “Yeah, Momma.” For some reason, I was cravin’ some cabbage, too. So I got me a big old plate, got that cabbage hot, and I put the rice on top of it. . . . And I had three pieces of ham hocks and two neck bones.

She said, “Eat it all if you can.”

But I said, “Well, I’m gonna leave you one ham hock and a little bit of this cabbage just in case.”

I got in there in front of the TV. And my plate was like this here, you know [holding his hands ten inches apart]. And then, oh yeah! She gave me some hot water cornbread. It was about half of a skillet of it left, you know. And I was fixin’ to cut me a piece, but Momma said, “Go and eat the whole thing.”

I put a little juice on top of the cornbread, make it a little softer, put a little hot pepper on there. And got to eatin’!

Next thing I know, man, I’m scraping the last little bit. Damn, that food’s gone. I said, “Momma, you sure you don’t want none of this?”

She said, “No, eat it all. You must have been hungry, boy, huh?”

I say, “Momma, I was. You know, being out there on the streets, you don’t get no righteous kind of a dinner like this here. Plus the price would be too high, and that takes away from money you need to get high.”

This mention of money “to get high” triggered Sonny back to hustling:

Sonny: Hey, Philippe, buy these coasters for fifty-one cent [pulling them out of this shopping cart] so I got enough for two beers?

Philippe: Sorry, man, I don’t need them—

Sonny: [interrupting] You set them coasters on the mantelpiece. For the price, man, you cannot beat. Buy these from me.

Philippe: No thanks, man.

Sonny: [aggressively] Come on Philippe! Don’t do me that way.

Shortly after his niece’s wedding, Sonny’s brothers and sisters began visiting him under the I-beam where he slept, trying to persuade him to “come back home.” They offered to pay for a methadone maintenance program, but Sonny turned them down. He was proud of who he was, a righteous dopefiend and an outlaw. He rationalized his homelessness as evidence of masculine autonomy and self-control:

I can always go home and ask for help. But I don’t be trying to put that off on them. I just be struggling with what I have to do on my own instead of just running on into the house as soon as things get rough.

I have to try to make it out here on my own, man, and learn to deal with this shit, man! It’s a responsibility knowin’ that if I ain’t made no money, the next day I’m gonna be hungry.

And I never want to be dopesick in front of my mother. She’s never seen me that way. I’ll never let her see me that way.

Sonny was an all-American rugged individualist. He took full responsibility for his homelessness. When we asked him if childhood traumas might explain the situation of his peers on the boulevard, he responded aggressively: “I’ve heard that same old song all my life. People blame other folks for their problems. But once a person get a certain age, then he know right from wrong. Whatever you do is on you. It’s not on your parents and stuff. I believe everybody here had pretty good parents.”

Tina was also welcome at her mother’s house and in the homes of her extended family members, but they did not offer a supportive environment. Unlike Sonny, Tina had an unstable childhood. Most of her family members had not been upwardly mobile and were perennially engulfed in violent crises. Tina met her biological father for the first time when she was twelve, when he tried to reassert his patriarchal prerogative following an incident in which Tina’s “big sister” had been sexually molested.

We were living with my auntie on Fillmore, and one of my auntie’s mens tried to molest my sister, Sylvia. She was thirteen and he tried to feel on her titties.

My mother almost cut his throat and that’s when I found out about my daddy ’cause my mother called him. He came right over, hollerin’, “I don’t want no mans around neither one of my daughters!”

But my daddy was a rollin’ stone. He was already married to someone else. My mother was his mistress, evidently.

Tina’s last contact with her father was also precipitated by the violence surrounding sex work:

Last time I seen my daddy was at my sister Sylvia’s funeral. He never treated me like a daddy treat his daughter, but at the funeral he treat me so sweet because I wouldn’t move from the coffin. [long pause] Then he hug me [voice cracking], but I never had a chance to tell him how I felt.

Sylvia was stabbed in the back seven times. It was drug related. It was two black ladies and it was two tricks—a judge’s son and a lawyer. And the black lady stabbed Sylvia in the back and tried to throw her in the swimming pool at the Colonial Motel in Antioch, California.

The bitch that killed my sister got seven years. But she’s dead now. She killed herself; she ran into a damn telephone pole by the railroad in Antioch.

We went and identified Sylvia on Mother’s Day . . . and she lived seventeen more days and died on her birthday. It was thirteen years ago; she’d be forty-two today.

My daddy gave me five hundred dollars at the funeral. But I didn’t want no fucking money. Shit! I wanted my sister. And that’s the last time I seen my dad, at Sylvia’s funeral . . . and I haven’t seen him since. . . . And I won’t even try to find him, or call. No lookin’ up no numbers, no nothin’! Because I know he don’t want me. I already failed.

And his wife, she hate me. She was like in her thirties, and my dad, he in his sixties, and she say I look just like my mother. . . . And I do! My daddy used to say, “Tina, looking at you is lookin’ at your mother.”

Tina sought to reconstruct memories of childhood love and nurturance to redeem the chaos of her family:

We was living in the Sunnydale Projects and then my mother had another little boy. So it was two stepbrothers and then me and my sister, we had the same daddy.

I had got a tricycle that Christmas and I was so happy. It was red. My baby brother’s daddy bought the tricycle for me. His name is Arthur Scott. He was not my dad, but he was my real dad. I still call him “Daddy” today.

Arthur was a bus driver. He provided for us. And took good care of his son. He tried. But then he became an outlaw and his life ventured on.

But still I’ll go and I’ll see him and his mother, Mrs. Montgomery. I call her “Granny.” They used to have this shop across from Candlestick Park called The Candy Shop. They used to make hamburgers, french fries every day . . . real cheap.

Now they just at home, together. Mother and son. Yeah, but they’re real sweet to me. They still love me and they want me to do good with my life.

Tina sometimes sought respite from the street in her fictive Daddy and Granny’s home. But the stability and emotional support of her adoptive, ostensively loving kin-figures was imbued with instrumentality and straightforward violence. Tina’s commitment to kin reveals that there is nothing inherently positive in “strong extended families” when they are embroiled in drugs and violence. (See Jarrett and Burton 1999 on poor extended African-American families in flux and Stack 1974 for a counterclaim; see Fordham 1996:98 on the “culture of forgiveness.”)

After buying crack on Third Street, Tina decides to introduce me to her “Granny” and “Daddy,” who live around the corner. Granny shakes my hand gently and breaks into a welcoming, eighty-four-year-old’s toothless smile. She is wearing a blue muumuu with a matching silk scarf wrapped around her head and a gold beaded necklace around her neck. She immediately resumes her place in a rocking chair by the window.

Arthur greets me heartily, “The first man I ever met in San Francisco was named Jeff.” He is much shorter than I expected and is very thin. He is wearing a beat-up baseball cap and is carrying a bowl of quartered oranges in his left hand.

The room is covered with old family photographs, including a painted photo of Granny’s parents. She says that the image does not do them justice and that they barely look like how she remembers them.

While Granny and I chat, Tina and her Daddy hurry into the side room. I overhear, “So did you bring me anything today?” And a few seconds later, “That’s my good daughter,” followed by the scratching of matches, the bubbling of melting crack, and deep inhalations.

I ask Granny about the past, and she recounts the classic life story of an elderly African-American in San Francisco. Born in Mississippi, she migrated to New Orleans as a teenager. She left for San Francisco in 1943 and found work as a hospital aide. “At eighty-four,” she tells me, “I plan on relaxing and on enjoyin’ not working.” She has lived in this house, which she rents, for fifty years.

Tina and her Daddy return to the living room. The rush of their crack smoking dominates the rest of our stay: first they want to visit an uncle in the hospital; then they don’t; then we are all going to go to church; then we aren’t.

When we finally get up to leave, Tina pauses at the door and asks for an orange. Arthur hesitates but then slowly holds out his bowl. She frowns at the two slices in the bottom of the bowl and declares, “I want that one,” snatching the slice Arthur is holding in his hand. She then runs across the room and grabs her Bible, a large white volume with an image of Jesus embossed on the cover, and we head back out to Edgewater Boulevard.

The difference in tenor between Tina’s and Sonny’s family visits is accentuated by gender roles. As the favorite, first-born son, Sonny could graciously accept his mother’s nurturance and her desire to indulge him with his favorite foods. He was confident in his sense of entitlement to her treats. At the same time, he protectively made sure that she, too, had eaten her share (see Fordham 1996:147–189 on mothers socializing their adolescent boys to receive the entitlements of “black patriarchy”). In contrast, when Tina went home, her stepfather expected her to bring him crack. Ever since childhood she had gone to the street to escape domestic turmoil. Unlike the men living on Edgewater Boulevard, however, Tina sought to fulfill the role of caretaking daughter and grasped at any signs of reciprocal nurturance. She had to settle for shared drug use:

Arthur made Granny’s place a ho’ house! Bitches and niggas be coming in and out of there. That’s why I don’t like going over there no more. Bitches be suckin’ dicks and shit for crack. And Arthur, he gettin’ the money.

And then my Grandmama sitting there at the kitchen table, or at the window . . . and they just passin’ her by. So I’m like, “Bitch! Get outta here.” I’m gonna whip all them ho’s ass. Every last one of ’em.

[long pause] All of us fight. Me, my daddy, and my little brother, Dee-Dee. The three of us. But before my brother Dee-Dee went to jail, he and my daddy was so sweet to me. Now that I fix, they hold my arm when I need help.

Granny’s rapidly deteriorating health revealed once again the gendered division of labor in caring for vulnerable kin. Arthur often disappeared on crack binges, leaving his mother alone in the house with “nothin’ to eat.” Tina began to worry:

You know, Jeff, Granny, she is senile. It’s like this [imitating a conversation]:

“Hi, Grandma! I’m gonna take a bath.”

[feeble, slow voice] “You don’t have to tell me. You stay here anyway, don’t you?”

[normal voice] “Grandmother, can I have my clothes?”

[slow voice] “Why you keep tellin’ me, baby? You know where you stay.”

“Grandmother, I stay in the van with my friend now.”

“It ain’t no shower in there?”

“No, what is a shower doing in a van?”

You see, Jeff, I have to make her remember what a van is like. As soon as I walk away she don’t gonna remember. I was wantin’ to take her walking this week, but she don’t want to go out.

Last month, Jeff, I had to call the police on my Daddy two times to kick his ass. He was fussing and yellin’ and Granny told him, “I’m gonna kill you in your sleep!” She swung her cane at him and he grabbed at it and she fell.

Six months later, Granny was evicted by her landlord. She and Arthur were saved from homelessness by a city-subsidized housing program for the aged. Consistent with gender caretaker roles, Tina’s mother, Persia, who had been separated from Arthur for over thirty years, also stepped in to help her former mother-in-law.

Tina’s own ongoing relationship with Persia was framed by the same paradoxical continuum of love and abuse that characterized her relationship with her stepfather. Meshing love and violence and taking refuge in a sense of individual autonomy defined through drug use, Tina had consolidated a habitus that was effective for survival on the street as an addict. Although critical of her mother’s mistreatment of her as a child, she, like Sonny, took full responsibility for her drug use. She also held on to her sense of filial love.

Growing up was a bitch. My mother didn’t want me. I overheard her tell my daddy over the telephone, “I wish I wouldn’t of had her. I tried to kill her by fallin’ down the stairs.” I heard her say it several times. That’s how I know she don’t like me.

She been fucking me up ever since I was a kid. She used to beat the fuck outta me . . . with extension cords and telephone cords. I remember one was real thick . . . and I couldn’t dress for gym.

She scald her husbands, too. She stabbed the fuck outta the—was gonna kill one of ’em.

[long pause] Last time I seen her, she put me out of her house. She wanted to kick my ass so I got the fuck out of there ’cause I can’t hit her. [long pause again] I think about all that shit. [tearing up] It all comes back to me.

[raising her head] But it ain’t my mother’s fault I’m like this. I don’t blame her. I really don’t. I don’t blame her for my drugs. That’s on me. [lighting a crack pipe] I can’t keep putting that burden on my mother. The only thing she could do is just pray for me. She loves me. . . . But when she hurts me, I rebel from that. . . . But I don’t want to hurt her. I’m too much like her ass.

I only keep thinking about when she scratched my face up when I was eighteen [frowning]. My face was like a zebra. She thought I was gonna live with her forever, and I thought I was too. But then I tried to move out and she snapped.

I’ve never ever really told my mother how she made me feel when she beated me when I was little. She made me feel that she hated me. We talk, but I never tell her. . . . But I have to. . . . But if I tell her, maybe she would just really push me outta her life forever.

Yesterday it was Mother’s Day and I left a letter by her door on rainbow paper. I told her that I love her, and that I miss her, and that I want to be with her for a while. She was up in Vacaville [at the prison], visiting my baby brother Dee-Dee. He be out in December.

Tina made frequent references to her mother’s psychological instability, blaming it on the outlaw behavior of her brothers. “My mother been to Napa [state psychiatric hospital] and all that, Jeff. She snapped over my oldest brother. He worried her to death, that son-of-a-bitch jailbird—a burglar, in and out of jail. But he’s a minister now in Modesto.”

We took Tina to the beach at her request on several occasions. She wanted to evoke positive childhood memories on these outings. “I used to be at the beach, a little girl jumpin’ up and down in the waves. Once my mother was gonna kill her husband, but instead she got herself outta bed and told us, ‘Come on, y’all!’ And took us here. That’s why I love the beach. She used to get us up at three, four in the morning, ‘Let’s go wade in the water.’ ”

Tina racialized her explanation for why she suffered so much corporal punishment as a little girl, taking it back one more generation to her maternal grandmother:

My grandmother moved in and helped my mother take care of us ’cause my mother was a single parent. She was a beautiful lady. Oh, I loved my grandma. But she had picked the two oldest as her favorites. And the two babies—my baby brother Dee-Dee and I—we wasn’t shit.

[crying silently] My grandma idoled my older brother’s ass because he was born with blue eyes.

Jeff: Did your grandmother abuse your mother when she was little?

Tina: My grandmother didn’t even beat her, ’cause my grandmother was real black, and my granddaddy he was a white man, so my grandmother thought the world of her. But evidently my grandma was searching for something, and she beat the fuck outta me.

Jeff’s fieldnotes from his first meeting with Tina’s sixty-one-year-old mother, Persia, reveal a charismatic but emotionally overwhelmed grandmother who was trying to protect herself from the turmoil of her outlaw progeny, whom she could not stop loving. She was also beset by the anonymous violence and drugs that pervade most U.S. inner cities, including the public school system (Bourgois 1996a; Devine 1996).

In a bustle of high energy, in a half dance, half trot, Persia skips about the kitchen and insists on making me lunch. She speaks in a nonstop stream of consciousness and says that she has not heard from Tina in six months. When I tell her that her way of moving and talking reminds me of Tina, she smiles appreciatively, but then her mood shifts anxiously.

Persia: [softly] “How was she when you seen her last? How is she lookin’? [abruptly changing her tone] But what can I do? She’s grown. I can’t fuss. I just live in fear. So all I do is hope and pray.

[softly again] “I’m scared to get involved because everyone is on drugs. . . . [loudly again] My grandson, he’s getting drugs at school. [suddenly shouting] What can I do? I’m only one person! I have fourteen grandchildren! And they so bad!

[composing herself] “I don’t want no contact with Tina. Because I’m the mother and father, the uncle, the aunt, and all that, you know. Oh, God, I don’t know! Where can you escape to?

[softly again] “Is Tina okay? Tell her I love her.”

Persia shows me photographs from the time she “ran away” from her children to “take care” of herself. Just last week, she quit her job as a high school tutor because a student was murdered on campus. Seeing the feet under the sheet reminded her too much of her daughter Sylvia’s stabbing. “My first daughter, she’s dead. I had her when I was seventeen. She was a love baby. . . . [shaking her head] Tears and devastation . . .”

In much the same way that Tina spoke of her childhood, Persia overlaps the traumatic incidents of her daughters’ lives and enmeshes maternal love with rejection.

I got a lot of fightin’ over my children comin’ up. Drinking beer at an early age. Somebody had kidnapped Tina. Oh God! A nightmare, a heart attack!

[gently] I know she love me, but she’ll get rid of me in a minute. [suddenly angry] I’ve seen somebody early in the morning throw her something; she go get it and hurry up and get rid of me. I finally realized I can’t rescue her.

I was runnin’ my blood pressure, not sleeping. I just had those crying spells. But I’m over that a little bit now. I cry a little bit, but not every day, all day. I don’t make myself sick, ’cause there ain’t nothin’ I can do.

But I don’t want nobody to hurt her. Just don’t be out there on the streets with a cup! But if you see her, Jeff, tell her I’m not mad, that I be loving. . . . To take care of herself. And let me know about Carter, too.

Like Sonny, Carter came from a nuclear family, but like Tina, he was introduced to life on the streets inside his home before he understood what he was seeing.

My uncles on my mother’s side was dopefiends. I be wanting to play in the living room—[opening his eyes wide to imitate a waddling toddler] and they be like [husky voice], “Ah, I’m so tired.” That was a cover-up. They was noddin’. My mother knew it, but she never told us nothin’ about it.

Carter shared a bedroom with his older brother, A. J.:

My brother would make me turn over in the bed and make me hide my head under the pillow. But I could hear him making the rig. See, they had to make the rigs in those days. With a needle point, a rubber band, a tube, and baby bottle nipple. It was an art to it. They used a little piece of dollar bill, just the white part, and they roll it up and jam it so it fits snug with the nipple. Then I could hear the “squish, squish” sound of him squeezing the baby nipple.

And I used to see him standing in the playground in front of the rec center just nodding and shit. And I used to say, “Damn! Why someone gonna do that?” And I used to always look down on it.

They used to take sides of cows off the meat delivery truck. A whole half a cow with the legs on it and run with it to the All American Meat Market on the hill. These little scrawny, sick dopefiends carryin’ a whole half cow.

They used to intimidate Chinese Kim, the butcher: [shouting] “Cut this up!” And then go sell it door to door.

This one time they hid one of the cows in the bushes by the playground. It was a leg stickin’ out and I was tryin’ to drag it to go give it back, right. But I end up fallin’ backwards ’cause it was greasy. My brother’s other partner, the one who got blown away by a shotgun, caught me. “Little nigga, what the fuck is you doin’?” [motion of punching and kicking]

I’m crying [whining], “I’m gonna tell my brother on you.” He answers [deep gravelly voice], “You ain’t got to tell him. I’m gonna tell your brother.”

Then my brother got on my ass for doing that. “You little wannabe, motherfuckin’ innocent bastard.” [bending down to slap at an imaginary child with both hands] ’Cause that was their money I was fucking with. That half a side of beef was going to fix them for maybe two or three weeks.

An HIV prevention peer outreach worker who had been a running partner of Carter’s older brother, A. J., during the early 1970s remembered Carter as an earnest little boy: “We used to use [heroin] in Carter’s mother’s house. And Carter used to tell his brother to stop using. [chuckling] ‘Stamp out drugs!’ But then when we’d be goin’ out on a lick, Carter used to always want to follow us. A. J. would have to chase him home.”

Carter grew up in a large household beset by poverty and instability. He made passing references to “my father beatin’ on my mother,” but he also held on to vivid memories of a working-class propriety upheld by the virtuous women in his household:

It was the day before school started. And we was supposed to go to school looking nice and clean. We ironed all those school clothes we was going to wear and show off the next day. Laid them out on our beds. Had our books and our binders ready.

There was eight of us, counting my two nieces, who was living with us. And my mother was the only one working, so everyone had their little summer jobs to get their school clothes and everything.

That’s when the whole house burnt to the ground with everything in it and my sister got burnt badly. She was in the hospital for eight months in one of those incubators. She’s a nurse now. She dedicated her life to taking care of people.

Carter was proudest of his elder sister, with whom he had been living before becoming homeless, because she ran “a center for wayward girls.”

Most of the Edgewater homeless retained fond childhood memories of growing up in the neighborhood up the hill. Although gentrifying rapidly at the time of our fieldwork, this community of single-family homes was still largely working-class and ethnically diverse. Its main street was lined with all the amenities of an old-fashioned neighborhood: a public library, a community center, a baseball card shop, a bank, a barber shop, a butcher shop, a produce market, a supermarket, and several bars, corner liquor stores, and churches. In the “old days,” the neighborhood had been even more self-contained, boasting a movie theater (converted in the early 1980s into a Latino evangelical church) and a gas station (transformed in the early 1990s into the parking lot of a health food grocery).

During her third winter on the street, Tina once again left Edgewater Boulevard for California’s Central Valley to take refuge with her eldest son. He had just been released from a six-month prison term for a violation of parole on a four-year bank robbery sentence. Suddenly alone, Carter established a temporary camp behind the ice machine at the Crow’s Nest liquor store. He camouflaged his shelter as a mound of discarded cardboard boxes awaiting recycling. Caltrans had confiscated his blankets in a raid the week before. To try to keep warm, he created a cavelike vortex by stuffing small boxes into consecutively larger ones and insulating them with Styrofoam. We had to crawl on our bellies to enter his shelter, but he was proud that he had “hooked it up with music” by running an electrical wire from the ice machine to a boom box.

On an especially cold evening, Jeff and Hank happened to walk by and found Carter sprawled in front of his boxes, drooling in the midst of a heavy nod. With a flick of his cane Hank woke him up, teasing, “Wipe your mouth.” Startled, it took Carter a few minutes to shake off his grogginess and recognize us. When he finally stood up, he was stiff and shivering.

“Thanks for waking me up, Hank, I might have froze to death. ’Cause, damn! Caltrans took my jacket too, last week.” Jeff bought a round of food and drink, and they went back to Hank’s new camp. It was carefully hidden on the embankment behind an Apple Computer billboard featuring John Lennon and Yoko Ono. This reference to the 1960s set Hank and Carter to reminiscing about “life on the hill in the old days.”

Carter: Hank was the usher at the Liberty Theater, where the church is now. Everyone knew Hank.

We used to see two major features and two twenty-minute shorts for twenty-five cents—or was it fifty cents? I would work after school babysitting and save all my little earning money to go to the show on the weekend. The line for the theater used to be ’round the corner.

Hank: We had a whole variety of horror movies.

Carter: [excitedly] Yeah, horror movies! Taste the Blood of Dracula. I remember that one. Boy, that was good! Christopher Lee was awesome in Dracula, and Bela Lugosi too.

The only way I was allowed to go to the movies was if I had gone to church first. My mother and father was like, “If you ain’t go to church, you can’t go to the show.” We had to have the program from Sunday school to show we’d been there.

Hank: We used to play all these religious films like The Ten Commandments.

Carter: Hank, remember the five-and-dime store that used to be by the theater? And Bob’s barber shop?

Jeff: Did your parents go to the movies with you?

Carter: No, because they was always working. But on the weekends they was like [firm voice], “Take your brother!” Because I was younger. And after the movies, right, you had to hurry to get home, especially on a Sunday ’cause you had to get ready to go to school. It was gettin’ dark.

And after the last movie ended, everybody would be in a hurry to get to the door and we used to run down the hill trying to stay together. And you’d be lookin’ ’round ’cause you’d be scared, “Aaah! where’s Dracula?” [laughing] You might get snatched!

My sisters could run fast, boy! And I’d be like . . . [shrill voice] “Wait for me!”

[taunting voice] “You the last one. Dracula gonna get you!”

Oh man that was great! Jeff, if I could recapture those days. . . . Those are breathtaking memories.

Carter’s preadolescent innocence coincided with the height of the 1960s, when San Francisco was the epicenter of the hippie counterculture: sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. Some of the legendary rock stars from that era lived or rehearsed in the neighborhood.

Hank: Before Santana was discovered, he used to practice in a basement up here on the hill.

Carter: When Hendrix used to be at the Fillmore, he used to come play in a basement up here, too. They used to make us get away from the garage door ’cause we’d be blocking the street.

Hank: And every Sunday they had the “dope bowl” right at the top of the hill.

Carter: There would be ice chests with beer and wine and plenty of weed and they’d play football.

Hank: A few people would have some cocaine.

Carter: We had go-carts here, and the pole where they put a rope on it and you’d swing an easy fifty foot over the side of the hill. Like a Tarzan. You run and pull back, and you let go and scream, Whooooooo! [laughing]

Hank: And go way the hell out over the drop.

Carter: We’d run up to the pole hoping there ain’t nobody there and you was the first.

Hank: Yeah, “firsties!” [slapping a high-five and laughing hard]

Carter: [choking with laughter] Yeah, “firsties!!” We used to have fun as kids. Not like youngsters today. They don’t know how to have fun nowadays.

Hank: We oughta’ go fly a kite up there. Haven’t done that in years.

Carter: And we used to walk down the hill to the swimming pool in the Mission. It only cost ten cents to get in.

Hank: Oh that swimming pool was fun. But now you got motherfuckers hanging outside that pool selling crack.

Carter: This was a fantastic neighborhood back then.

Hank: If I could do it all over again I’d just want it to last a lot more years. Wouldn’t trade it for nothing in the world. I have a million memories.

Carter: A lot of the guys who drive by the corner here [pointing toward the corner store] don’t have a clue that we knew their parents.

Hank: They walk down here and right past us, but we see their parents in them. . . .

Carter: And they see us, but it’s [dismissive gesture], “Oh, the ol’ dope heads.” But this was a fantastic neighborhood.

Hank: I’m glued to the hill. I don’t want to leave the hill.

Carter: Y’know what? I don’t think I ever will. I’m gonna die here.

A more violent world of adolescent street gangs operated parallel to San Francisco’s hippie drug scene during the years when most of the Edgewater homeless were teenagers. Following the ghetto race riots, the federal government began funding innovative social programs for at-risk youth, through the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). Carter, for example, joined an African-American youth gang that was subsequently recruited into a federally funded program known as Youth Organizations United (Y.O.U.), founded by former members of the Conservative Vice Lords, a Chicago-based gang (Gang Research.net 2006a, 2006b).

Carter: After school they had workshops, and we’d learn different trades so that after growing up we’d be getting into the business field after graduation . . . and being productive citizens and everything. The organization ended up lasting maybe five years or so. There was twelve states represented in the West, and organizations throughout the East Coast and the South. It advanced a lot of kids and students.

We wrote up a program with curriculums and formats and everything and we did fundraising and interchanged ideas. And I swear on my life, my right hand to God, Sammy Davis Jr. wrote us a check for five thousand dollars. [chuckling] Didn’t nobody have a pencil, and he wrote the motherfuckin’ check out in green crayon.

Then the HEW funding ended and I went back to being a bum.

The experimental social services of the late 1960s and early 1970s that briefly channeled Carter’s energies away from gang fighting were short lived. By the age of sixteen, he was incarcerated as a juvenile delinquent on a fast track to a career in crime. Thirty years later, however, Carter still reminisced with pride about his participation in Y.O.U. As we have noted, Carter crossed ethnic and class barriers more readily than the other African-Americans on the boulevard, and he was especially effective at dealing with us. Y.O.U.’s programs may have contributed to his slightly more diversified repertoire of ethnic and class-based symbolic capital (Bourdieu 2000; 2001:1–2, 33–42; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992:162–173, 200–205).

Adolescent street gangs also propelled Sonny onto the same fast track toward a career of criminality. Sonny’s family, however, unlike Carter’s, was not overwhelmed by economic crisis, domestic violence, or drugs. His working-class parents had achieved the American dream of owning their own home. But it was located next to a violence-plagued housing project, and Sonny was drawn into the local teenage peer group.

With the notable exception of Al, none of the whites had joined gangs or spent time in juvenile custody. In contrast, all the core African-Americans in our network had been locked up for gang activity as adolescents. Joining a gang had become self-evidently “cool” and brave to black teenagers growing up in poor neighborhoods. This option was not as readily available to white boys because by the 1970s white gangs had largely disappeared from most San Francisco neighborhoods, and the new black and Latino gangs were increasingly segregated. Even those whites on Edgewater Boulevard who came from abusive and alcoholic families had not been incarcerated as juveniles. Significantly, when we asked Carter about drug use among boys in juvenile jail in the early 1970s, he responded bemusedly:

Drugs was taboo. . . . [squinting distastefully] Pathetic! Heroin, cocaine—I was so down on that shit! [giggling] That was the worst thing a person could do. I don’t think too many people up there [in juvenile jail] at that time even knew too much about those drugs.

In short, poor African-American boys were being formed into professional outlaws before they began to use drugs, whereas poor whites embarked on criminal careers later in life, after their drug use had spun out of control. This historical, institutionalized ethnic pattern from the 1970s was a crucial generative force shaping the contrasting dopefiend habituses of outlaw versus outcast that became visibly racialized on Edgewater Boulevard in the 2000s.

The proliferation of segregated youth gangs coincided with President Richard Nixon’s declaration of the War on Drugs in 1971 and the shift in funding from social services, education, and job training to law enforcement. Police records from the era note with alarm the disproportionate number of African-American youths being jailed in San Francisco. In 1974, for example, African-American boys were 2.5 times more likely to be held in custody than white youths (Juvenile Court Department 1975:19). A San Francisco task force on juvenile justice from the period warned that disparities in adolescent incarceration rates threatened to shut the current generation of African-American youth out of the legal labor market, “since many employers in the private sector think that commitment to CYA [California Youth Authority facilities] is similar to a prison sentence” (Bay Area Social Planning Council 1969:716). In other words, in the 1970s, the administrators of juvenile justice predicted the long-term criminalization of black youth that became so visibly institutionalized twenty-five years later in California’s apartheid-like prison system of the 1990s and 2000s (Public Safety Performance Project 2008:6, 34; see Wacquant 2001a:95–96 on the “hyper-incarceration” and “containment of lower class African-Americans”).

The ways that institutional and historical forces channel vulnerable cohorts of youth into crime, violence, and drugs are generally misrecognized. Following the logic of symbolic violence, involvement in illegal activities is usually considered to be a personal choice that reveals an individual’s moral defects. The structural political-economic forces that are in fact at work operate “invisibly” at a more subtle, long-term, and incremental level of habitus formation. Drug use, crime, and homelessness, therefore, are widely suspected to be evidence of laziness, lack of intelligence, biogenetic disability, or inadequate impulse control. Following historical patterns of racism, ethnic markers of habitus frequently emerge as stereotypes, which, in turn, are oppositionally celebrated by members of stigmatized groups in a display of resistance or as an assertion of dignity (Katz 1988:ch. 7; Levine 1977:407–419; Marcus 2005:24–30). In routine interactions, the political-economic basis for the racialized habitus formations of middle-aged African-American outlaws and white outcasts on Edgewater Boulevard are hidden because their everyday behaviors express themselves as the purposeful actions and conscious choices of individuals.

The African-Americans did not have a critical awareness of the historical institutional forces that had shaped the last twenty-five years of their lives, as the United States quadrupled the size of its incarcerated population and imprisoned six times more black men than white men (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2004, 2005; Public Safety Performance Project 2008:6, 34). Instead, they reminisced about juvenile jail with nostalgia and masculine camaraderie, as though swapping stories about summer camp or varsity sports.

San Francisco’s main correctional facility for juvenile recidivists, known as “Log Cabin,” was set in a redwood forest outside San Francisco, surrounded by state parks on the hills above Silicon Valley. Enormous public resources and effort were spent on what became a de facto racialized training ground for professional criminals.

Sonny: The South Park neighborhood was fighting the Medallions from the Fillmore. I was in the Conquistadors and we was helping the Fillmore Medallions. There were two different Medallions, one in the Fillmore, one in Potrero. Anyhow, we all got busted and went to juvenile hall. I did a year behind that shit.

Carter: Were you in the B-5 wing? That’s where I was.

Sonny: We were the first ones that broke in B-5. The very first! They called it “high risk.” [chuckling] The maximum security wing.

Carter: [explaining slowly] See, they had wings. Like B-1, B-2, B-3. B-1 would be like young, young kids. B-2, a little bit older; B-3 was considered the big boys. Sixteen and seventeen.

Sonny: I went through all of them wings, man.

Carter: [turning to Philippe] It’s like a boys’ home. You had beds going down rows inside a big dormitory. It was old-fashioned, solid wood.

Sonny: And you used to get what they called gigs on conduct.

Carter: Gigs! [laughing and high-fiving with Sonny] That’s right, gigs. [turning back to Philippe] You sit down for evaluation periods every six weeks at the dinner table, and they read off who made what. And after so many gigs you get bounced, demoted. You get gigs for cussin’ out counselors, serious gigs that rank you. I got bounced three times.

Sonny: Yeah. I got bounced. That gives you an extra month, like for a fight.

Carter: It wasn’t that bad. See, everything was wide open. You weren’t behind no bars.

Sonny: It’s all redwoods up there. It’s beautiful.

Carter: Oooh, some kind of beautiful, know what I’m sayin’? On your birthday they would bake you a big ol’ cake and ring a little bell and say [deep voice], “I would like to announce today is the day of your birthday.” And everybody sang “Happy Birthday.”

No one wanted to run away because out there in the woods there were some brown bears that would come down, and mountain lions too.

And they had everything you wanted up there, man. They fed you three meals a day.

Sonny: And you’d get to smoke six cigarettes a day. Six light-ups a day, and if you get caught smokin’ when it wasn’t light-up time, they give you a gig. That’s a minor gig. . . .

Carter: And they had a little pond where they had some horses, and they’d let you run around the pond on holidays and stuff.

For Carter, incarceration may have been a relief from the substance abuse and fighting occurring in his home. Log Cabin facilitated family bonding and reinforced his budding sense of masculine self-esteem:

Your whole family could visit, and you could walk around and show them the pond. I got a picture at Log Cabin with my mom and dad and sister and girlfriend. They used to visit every weekend. That was a big thing, to be sent away from your family. So they would be there every weekend and try to console me. “Don’t worry about it, son. It’s gonna be all right. Just hang in there. Only six more months.”

I likeded it. You do everything you want to do, you know, work all day, eight o’clock to two. I was on the crew building the rock wall.

Later in Carter’s life, many of the major liminal rituals that bring families together, such as funerals and births, continued to be mediated by the prison system. This institutionalized removal of able-bodied males from their families for long periods, interspersed with intense bonding through brief kinship rituals, parallels the way many of the African-American families continued to integrate aging homeless sons, fathers, and uncles into holiday celebrations and periodic family reunions.

Carter: When my father passed away I was in jail. When my mother passed away I was also in jail. But I got to come home for both of the funerals. Then I had to go back again.

Sonny: [softly] I lost my first son, Sonny Junior, God bless his soul, when I was in San Quentin doing a [parole] violation. April 14, 1988.

Mothers bore the brunt of the pain and destructiveness of their homeless, addicted children. Of everyone on Edgewater Boulevard, Felix and Victor had the most intense, on-again, off-again relationships with their mothers. They subscribed to a patriarchal discourse often associated with Latin American and circum-Mediterranean cultures and with Catholicism, which celebrates a son’s privileged relationship to a saintly, long-suffering mother whose self-sacrificing love enables her to forgive a son’s youthful masculine transgressions (see Belmonte 1989:87–94; Melhuus and Stolen 1996; Stevens 1973).

Felix: My mom’s a saint. Oh yes she is! A saint. She’s the best woman. . . . She’s my best friend.

I don’t ever tell her I’m homeless. That’ll break her heart. She’ll have a heart attack. I tell her I live in a hotel and that I’m trying to get into a program. She knows I’m a dopefiend.

Whatever she says to people about me when she’s angry, she still knows I’m her best friend, too. Me and mom are close. I take care of her. Whatever she needs, I’ll do it.

I love my mother more than anyone in this world. I wouldn’t ever want to hurt her. She’s the greatest.

When we first met Felix, his younger brother, a California Highway Patrol officer, had filed an order of protection with the court to keep Felix out of their mother’s house. Felix accused his brother of being “nothing but a prima donna, no-good, son-of-a-bitch, too-good-for-the-world Republican.” We learned subsequently, however, that a dramatic event had been the straw that broke the camel’s back: Felix had sold his mother’s furniture to pay for a crack binge while she was away on vacation. Furthermore, throughout much of his twenties and thirties, Felix sold heroin out of his mother’s garage. “The police kicked down my mother’s door six times,” he told us, somewhat proudly.

Nevertheless, Felix still sought out his mother in moments of emotional crisis, and she usually accommodated him. For example, when a peripheral member of the scene who had just been released from prison died of a brain aneurism while smoking crack in Felix’s tent, Felix called his mother from a pay phone, begging her to let him spend the night in her house: “Ma. I gotta get outta here. Someone died in my room.”

Most of the Edgewater homeless admired Felix’s mother and referred to her politely as “Mrs. Ramirez.” Their respect, however, did not stop them from hustling money from her for heroin.

Frank: Felix’s mother is awesome. Jesus Christ, she put up with Felix’s shit for so many years.

Felix would call from a pay phone, but he’d make it sound like he was at some hospital somewhere across town, trying to get into some treatment program, right. Then he’d hand me the phone. I knew the scenario.

[clearing his voice officiously] “Oh, yes, Mrs. Ramirez. This is Dr. Lombardi. And, um, yes . . . your son is here. And, yeah . . . he’s applied to enter our program and . . . ah . . .” [voice trailing off] And so forth and so on.

I played so many different characters. I’ve been doctors, lawyers, psychologists, cops, social workers—you name it. All to get a twenty-dollar or twenty-five-dollar initial payment.

Max: [laughing] But she’s a smart lady, really nice.

Frank: Yeah! She’s always asking Felix how I’m doing.

Halfway through our fieldwork, Felix was hit by a Pizza Hut delivery car in the alley behind the A&C corner store. The county hospital performed two surgeries on his left knee. The doctor’s release order specified, “Maintain leg elevated at home.” Felix complied by moving under a freeway overpass and using the support beams as a prop for his leg. He eventually settled out of court for four thousand dollars in damages from Pizza Hut. It was paid to his mother, who doled out the money to him in daily increments of five dollars. She had suffered a heart attack shortly after the lawsuit, and she allowed Felix to move back into her garage “to watch over her.” He felt redeemed, reporting the details of her health condition to us whenever we saw him on the boulevard: “Ma’s doing much better now. The holidays were stressful for her because my father died and his grandfather died at this same time of year, but we got through it.”

Frank grew up in San Francisco’s North Beach housing projects. He described his mother, a painter, and his stepfather, a writer, as “bohemians with a lot of creative friends but no money.” He referred to one of his babysitters as “a famous black poet” from the “Beat generation.” Like Sonny, Frank was the only child in his family to use drugs; unlike Sonny, however, Frank was not welcome to visit his parents or siblings:

I’m the only black sheep of the family. I haven’t called my stepfather in ten years—or any of my brothers. It’s been so many years, I don’t even know if they have any kids or not. I’m embarrassed to even call. What am I going to say? [long pause] I don’t want them to see me like this. I keep putting it off, and the more I put it off and all the years go by I keep getting more embarrassed.

[softly] It’s like a trap. I’ve got to call them sooner or later. [standing abruptly] I need a cigarette; you got one?

Frank’s stepfather—whom he referred to as “father” or “dad”—worked seasonally for the Forest Service as a fire lookout when Frank was in elementary school:

We lived in a little house in the forest every summer, in the middle of nowhere. We had no electricity.

No TV or nothing. At night we’d all climb on my mother’s bed—me, my mom, my father, and even my little brother who was just a baby, and my dad read a few chapters out of some old classic. I loved it! [smiling] I lived all day for that moment. I’d lie there and just close my eyes . . . just listening, drifting. It was one of the most enjoyable moments of my life.

He read every classic there was: Gulliver’s Travels, Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer, Wizard of Oz, King Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table, Connecticut Yankee. Just every classic you could think of . . . Alice in Wonderland, Wind in the Willows—Froggie “Beep! Beep!” [laughing] at Toad Manor.

It’s too bad that kids today just sit in front of the TV and the video monitors. They lose a lot. Reading is the best thing you can do for your kid. They get more out of that than watching TV any day.

Frank also had fond memories of his biological father, and he worked for him for several years as a sign painter when he was a teenager and young adult. Frank took us to visit him in a gentrified San Francisco neighborhood a short bus ride from Edgewater Boulevard. As we approached the three-story house, admiring the million-dollar panoramic views of the Golden Gate Bridge, Frank suddenly became nervous about a spot on his shirt.

His father answered our knock, surprised but gracious. He had not seen his son in several years, but he agreed to be filmed on video with Frank at his doorstep. We could hear Frank’s stepmother shouting angrily from inside the house, forbidding Frank from entering.

Although father and son resembled one another physically, their very different demeanors in front of the camera uncannily highlighted their distinct positions in the world. Frank’s father was a retired self-made contractor, and he stood up straight, looking directly into the camera. He spoke in a soft voice with a gentle, resigned tone, intermittently smiling or frowning at his son. Frank squatted on the ground and remained hunched over throughout the entire interview. He spoke with the gravelly rasp of a long-time heroin addict, looking downward most of the time. Struggling not to argue or interrupt, he occasionally squinted anxiously at his father, flinching at his criticisms and perking up at his compliments.

Frank: You’ve lost a lot of weight, Dad.

Father: Yeah, I lost about fifteen, twenty pounds.

Frank: [worried] Damn! Are you okay?

[awkward silence]

Father: I really don’t know what I could say about what happened to Frank and why he’s been on the street for the past twenty years. Because he didn’t have to be. I mean, he was a talented sign painter and had at least three years of college and studied photography. He had the support of myself and his brothers. If he had cooperated—but he didn’t.

Philippe: It must have been hard for you?

Father: Yeah, you know at first it was. But you see, I was raising another family with three children, and Frank’s mother and I had been divorced for a lot of years at that point—ten years I guess. Frank was almost like a stranger in a way when he came to live with us in his senior high school year. His stepfather and his mother had moved to Idaho. . . .

Frank was working for me part time then. In fact, we built this house. He rented a little shack in back with a group of rock musicians in 1970. I guess that’s when the drugs started. . . . [smiling uncomfortably]

Frank: [wincing in agreement] About then . . .

Father: Well, or a little before. . . . Then he moved out to live [turning to Frank] with that girlfriend, the beautiful blonde [smiling].

I went over to Frank’s new place and saw this table with this giant bowl of cocaine and this big cigar box full of Acapulco Gold. And I said, “Frank, do you know what this does to people?” ’Cause in those days you could go to Haight-Ashbury and see what was happening.

And he says, “Oh, I can handle it.”

And I said, “Frank, you can’t handle it.”

But we absolutely couldn’t talk, so I finally gave up trying.

But then I bought him a truck and some equipment to go paint signs on subcontract. . . .

Frank: [eagerly] I worked for years doing that. . . .

Father: Well, he worked off and on, except he’d get on these drugs, and . . . [voices overlapping]

Frank: Well, except when I was dealing. . . .

Father: And the jobs wouldn’t get done. And I’d lose the accounts. . . .

Frank: Well, it wasn’t that bad. . . .

Father: And finally they had a few accidents and totaled the trucks. . . .

Frank: That Yellow Cab hit me. That wasn’t my fault! I won the lawsuit. They hit me and screwed up my back for three or four months.

Father: Well, whatever. It’s the drugs that screwed your life up, not the cab, not the wreck. . . .

Frank: Well . . . [nodding] absolutely.

Father: He was always getting me in debt, which I couldn’t afford. I mean, I had three other kids, small children. Finally I said, “Frank, this is it.”

He went his way, and I went mine. And it’s been that way for the last fifteen years.

Frank: [quietly] Well . . . yeah.

Father: I try not to see him, and he tries not to see me.

Frank: We still . . . I mean, you know . . . [wincing] I love my dad, but . . . I understand that . . . you know . . . it’s not a working relationship. It’s kind of tense.

Father: You see, I’m seventy-four years old. I had a quadruple bypass. I got Crohn’s disease. I look almost as young as he does! [frowning] I don’t know, I can’t comprehend it. . . . And I finally gave up trying to because . . .

Frank: [loudly] Tell them how I got started, though.

Father: I don’t know how it got started. Oh, you mean your mother and I breaking up. . . .

Frank: No, no, no, no! I’m talking about when I had all that money. The only reason I got into the heroin in the first place was because I was dealing it. . . .

Father: I didn’t know if you wanted me to bring that up [pointing to the camera]. But yeah, I remember that.

In the early 1970s he invited me over to his place and there was a drawer full of about a hundred thousand dollars in cash. And I said to Frank, I said, “Well—” [stopping suddenly and turning to Frank]. Are you sure you want me to mention who you were selling to?

Frank: I don’t even remember who I sold to.

Father: Well, it was the Jefferson Airplane. And his friend was bringing it in from Vietnam.

I said, “Frank, there’s nothing I can tell you that’s going to make you do anything differently, but I’ll tell you what I would do: I would get rid of this stuff.”

Frank: [smiling] No, you wanted me to invest it in real estate!

Father: And what’d he do? He reinvested it in more drugs. And of course his partner got caught and did twenty years in a Bangkok jail. It was terrible.

Frank: But you don’t know what you’re getting into when you do that sort of thing. I certainly didn’t know. I didn’t plan on getting hooked on drugs. If I had hindsight now I would never do that again, but I was young and stupid and was having a good time. It was 1970.

I had all the money in the world and I didn’t think I was ever gonna work again.

That’s how you get started. I started smokin’ it, then snortin’ it. . . . And then one thing led to another. You don’t expect to get hooked on it. You don’t expect that to happen to your life. . . .

Father: Well, I certainly would have expected it if I started, so I never did.

Frank: [defiantly] No, you don’t expect it. Nobody does! What do you think . . .

Father: [exasperated] What do you mean “nobody does”? Sure you do!

Frank: [loudly] Not one single person out there that’s hooked on a drug, or alcohol, or anything expected to be. . . . Nobody does!

Father: [throwing up his arms] I don’t know how you can say that, Frank. It’s just inconceivable to me that you didn’t think that you were going to get hooked on something that you were doing every day.

Frank: What! Do you think somebody’s gonna do that deliberately, thinking that they’re gonna get hooked? Of course not! I had no idea! I thought I could stop any time I wanted to. I had absolutely [shouting] no idea that I was ever gonna get hooked on drugs! None whatsoever!

Father: [gently] Well okay, okay, that’s fine. But we just go around in circles on this. [shrugging] What difference does it make? You got hooked and you basically committed suicide. Basically that’s what you’ve done, Frank. Huh?

[Frank shaking his head and clearing his throat as if to say something, but swallowing hard instead]

Father: You’ve been dying for twenty years.

Frank: I’m not dying. In fact I’m perfectly healthy. I just had my blood test come back. They told me my liver’s fine. My cholesterol is excellent. My kidneys are fine. My blood pressure’s perfect. Everything’s normal. They told me I’m perfectly healthy.

Father: You don’t look that great. Maybe you’re malnourished. Maybe you’re not eating. . . .

What about the drugs and the booze? Are you giving those up?

Frank: Yeah, well . . . I’ve been working on it. I mean . . . I stopped for a long time. And I kind of fell back again. Uh, I’m trying to stop again. And uh, you know, going to these programs. Y’know, I’m trying to do what I can. But you know, I’m not committing suicide. . . . I guess you could say I’m trying to, but so far I’m not succeeding ’cause I’m healthy.

Father: [turning to Philippe] Frank came to live with us for one year in the seventies when he broke up with his old lady . . . or whatever you call her.

And he kept getting high and fighting with his brothers and sisters. They were only ten and thirteen years old. I’d go around the house, and upstairs in the loft would be little piles of matches where he’d been cooking his—what is it? Coke?

Father: Dope. Whatever. There in the basement, in the bathroom—jeez! So finally, it got to the point where I kicked him out.

Frank: No. I left.

Father: . . . Or he left. Whatever.

Philippe: How did Frank do in school when he was a kid?

Father: I think he did all right. Didn’t you, Frank?

Frank: Average.

Father: Average?

Frank: Yeah, average. I had a lot of problems in school. I had fights all the time. Yeah, I got kicked out of that one school and had to go stay with my dad for three or four months. Then I went to another school and had fights there.

Father: [nodding] Had fights there . . . and then he went to Idaho to live with his mom. And had fights there. So they finally sent him to Canada to a special boarding school.

I don’t know, [sighing] possibly it’s the broken home problem. [addressing Frank] You’ve had—what? Two half-brothers by your mother and stepfather.

Frank: I always felt like I was on my own. You know, always kind of felt in the middle of everything. . . .

Father: A sense of rejection or something?

Frank: Even when I was a kid, for some reason I always wanted to leave home and go do what I wanted to do. Independent, I guess.

Father: But I hired Frank and gave jobs to all his junkie friends ’cause I was trying to help Frank out. But also because they worked fine. They’d say, “As long as I got the heroin I can function normally. It’s when I don’t have it and have to look for it and find it and connive to get it, that’s when—”

Frank: When you got heroin in you, you can work all day long, like a bastard. But when I was sick I wasn’t worth shit!

[turning to Philippe] See, he could never understand that. And I never really wanted to tell him what was going on.

Father: We’d be ten stories up in the air and off Frank would go, sliding down the rope to “get a drink of water” or to “go to the bathroom” or something. It would drive me up the wall.

He went down the wrong rope once, too, and fell five stories. Almost killed himself [laughing].

Frank: I damn near did kill myself that time. Fucked my hands up real good.

Father: Anyway, what can you say? It’s water under the bridge.

Frank’s father died two years after this interview. According to Frank, in the weeks before his death, his father was in terrible pain and begged him for enough heroin to overdose himself. Two days after the funeral Frank was still dressed in the new clothes given to him by his half-brother. When we visited him in his encampment, he was carefully rolling up the sleeves of his pin-striped button-down shirt to avoid getting it bloody. He had surrounded his sleeping area with religious figurines—a twelve-inch statue of the Virgin Mary and a framed picture of Jesus. Max was consoling him.

Frank: [softly] I miss my dad a whole lot. He was a good man.

[angrily] They fucked up at the hospital. They were giving him the wrong goddamn medication for a long time.

Max: [putting his arm around Frank’s shoulder] Damn! That’s what gets me mad.

Frank: [yelling] It was the insurance company’s fault! His treatment was too expensive. They ought to take the heads off of all those company bureaucrats and shoot ’em. Fuckin’ medicine-for-profit!

Max: [gently] Frank, you can’t bring the man back.

Frank: [softly] I wish my father had outlived me. I truly wish it. He was a great man.

Frank received seven thousand dollars as his share of his father’s estate. He bought a twenty-five-foot-long 1978 vintage motor home, complete with toilet, shower, kitchen, pantry, closets, and refrigerator. He also rekindled a relationship with his favorite half-brother, the one he used to protect in high school “to make sure he didn’t get jumped by two or three of them niggers.” The motor home, however, failed to pass California’s smog test, making it impossible for Frank to register it legally. Soon the engine stopped running, and within a few months the police had impounded it. He blamed his half-brother for not lending him the money to fix it, and their relationship, once again, broke down. Frank became so despondent that he stopped talking except to ask whether anyone could find an “extra-large” syringe. The Edgewater homeless dismissed this suicide threat as hyperbole. As Max commented, “Where would he get the money to buy enough dope to kill himself, anyway?”

Subsequent conversations with Frank’s half-brother revealed that he empathized with Frank’s plight and worried about his welfare, but he could not figure out how to help him productively. We gave him a copy of our video of the conversation between Frank and his father, and he called us back shortly after watching it. He wanted us to know that Frank’s idealization of his father masked significant childhood trauma. As an example, he told us that, shortly after his father’s divorce, on one of Frank’s visits home, his father’s girlfriend “threw a pot of hot coffee over Frank’s head while he was sitting on the floor playing a board game with my dad. She wanted all the attention.”

Hank, in contrast to Frank, grew up in a large nuclear household with an exceptionally violent alcoholic father. All of Hank’s siblings, four brothers and three sisters, became addicted to heroin. The body language accompanying his accounts of his father’s violence evoked his Vietnam vet PTSD stories. Initially we suspected that his dramatic stories of childhood violence might be exaggerations, if not outright confabulations, on par with his Vietnam tales.

Hank: My dad was what you would call a common drunk. The guy worked hard. He did what he had to do in life to support his kids, but he was very stern, and there was no other way but his way. And my mother, she was kind of a . . . moot person. . . .

He broke her fingers one time. And when he done that . . . I said, “Hey Pop. You’re a man. I’m a man, right?” I grabbed him by the shirt and I banged him up. “You ever touch my mom again and I’ll kill you.”

He even pulled a gun out on me. I had to knock the handgun out of his hand, you know. I could have shot him. In fact, I put it against his head and tilt it back and I go, “Hey, I got the power now, don’t I? You like the violence?”

“What violence?”

“The violence that you instilled in me.”

I’m the youngster, and at that time I was like two hundred eighty pounds. I’m standing six feet. I had a martial arts background. And I’m street savvy.

I never took his manhood pride away from him. He’s a French-Polynesian. He would have shot himself before he lost his dignity.

I was scared of my older brother Steve, too. He was extremely violent. He beat me with a baseball bat one time. Beat me with a pipe another time.

He always beat up my sister Barbara. I was tired of seeing her hurt all the time. She was [high-pitched voice], “Hank! Help me! Help me! Help me!”

[speaking slowly] And I did the best I could, but out of fear, out of fear, I wouldn’t attack my brother. But one year I did.

Hank’s sister Barbara was also a heroin addict and spent six months homeless on Edgewater Boulevard after losing her job of seven years. She had worked as a cook at a private university in San Francisco. She had been sleeping on the couch in the housing project apartment of her PCP-addled eldest daughter. Like Hank, Barbara was affable, generous, and effective in the moral economy. She confirmed Hank’s violent, oedipal stories. The brutality reflected in her accounts made us realize that Hank’s PTSD was very real—but it had been caused by domestic violence rather than combat in the Vietnam War. For Hank, as for Tina, the street was safer than home during early childhood.

Barbara: [whispering] I remember being picked up by my neck and hung on the wall by my dad. Did Hank tell you about that?

Our father was French-Polynesian, from Papeete. He worked in the shipyards. But see, he wasn’t pure, and he came out light-skinned. They do things differently in Tahiti and he went back and forth until he stayed in San Francisco. But he would get drinking and start getting crazy, bust up the house, beat on my mother.

His first wife cheated on him a lot. He caught her in bed with his best friend. And he had this thing about how all women were whores. ’Cause I know when I was young he always called me a whore.

When our little sister Mimi was born, she came out with a lot of dark hair. They had just come home from the hospital, and he picked Mimi up by her legs and threw her, saying to my mother, “This ain’t my baby!”

And I thought, “Oh, my God. He’s going to kill the baby.” And like, I’m crying and begging him, “Please put her down!” And he started in on my mother. And he just ripped off her robe, and my mother’s just crying. She had just got out of the hospital. [flat voice] My father was cruel.

[speaking faster] And it bothers me now. I was little and I remember seeing him knock my mom out. I was crying. And then his trip was [deep, friendly voice], “Come here my little whiteybichette”—that’s French for “little deer.” “Come sit on my lap.” Then he’d give me a Lifesaver. “Oh, your mom will be okay.” And I’m looking at my mother, knocked-out on the floor for no reason.

One night, I remember all these lights were coming through the windows. I didn’t know what was going on. All of a sudden this big ol’ rifle—to me it looked really big—was pointing at me. And I’m against the wall. I’m scared as hell. I don’t know what’s going on. And all of a sudden someone just grabbed me, blanket and all. And we ran out the door.

It was my aunt who came in and got me out of there. It was my dad who was going to have a shootout with the goddamn police, drunk again. I remember a lot of things. It was horrible.

Philippe: Hank told us your father pulled a gun on him once. Is that true?

Barbara: It’s true! My father pulled a gun ’cause Hank was stealing everything out of the house. Everything they worked hard for, Hank was taking it. Because Hank didn’t have friends. He bought his friends. He was a loner, and he was a big, fat, pudgy kid . . . real quiet. But he’d do anything for anybody. He’s got a heart of gold.

But people take advantage of it. And these idiots would get Hank to go into the house and steal everything. I mean, he stole my mother’s diamond necklace. He stole everything they had, projectors, screens, cameras, whatever. But Hank wanted to have friends, and that’s what he did to have them.

Philippe: And this is before he had a habit?

Barbara: Oh he had a habit by then. See, my father got really sick of all the thieving. And they got in a fight and my father pulled a gun on him. They were wrestling on the floor. The gun went off. Put a hole in the hallway, and the bullet went right down into the garage.

My mother screaming, “Stop! Stop!” But she loved my father, no matter what. My mother had a real tough life. She’d tell me stories. When she was a kid in Salem, New Jersey, they used to be starving. She would go to a watermelon patch and steal the watermelons out of the neighbor’s yard.

She was into God and sent us all to Sunday school—Simpson Bible College on Silver Avenue, where the L train stops. I think it’s some Chinese school now.