I never let anybody get close to me. But when Petey walked into my life . . . I couldn’t stop it. It is hard to put it into words. It’s a closeness thing. It’s not about sex, never was. I really love that guy.—Hank

During our first year of fieldwork, the city of San Francisco undertook its first major evictions of the Edgewater Boulevard homeless encampments. Following the “zero-tolerance” policies pioneered by Mayor Rudy Giuliani of New York City, the mayor of San Francisco, Frank Jordan (a former police chief), instituted the “Matrix Program” (San Francisco Independent 1997, October 21). The city’s police force began issuing tens of thousands of tickets for “quality of life crimes” such as jaywalking, loitering, panhandling, and drinking and urinating in public. The rusted shopping carts many of the homeless used to keep their possessions safe were defined as stolen property. When homeless individuals failed to appear in court to pay misdemeanor fines for possession of stolen property, their shopping cart citations became bench warrants that triggered felony charges and arrests.

With bulldozers and backhoes, Caltrans clear-cut the brush along the freeway embankment bordering Edgewater Boulevard, exposing dozens of formerly camouflaged camps. Garbage trucks ground up several tons of mattresses, tents, blankets, and clothing along with the scrap lumber of ramshackle lean-to shelters. We thought this law enforcement offensive would break apart our homeless community and anticipated having to refocus the study. To our surprise, the social network survived. Its members temporarily split up into mobile groups of twos and threes, following the micrologics of alliances in the moral economy.

On the morning after the first large-scale eviction, we arrived on the corner in front of the A&C corner store to find Petey crying. During the night, Scotty had died of an overdose in Petey’s arms. They had been sharing a blanket to keep warm on the floor of the rented room of one of their regular customers, where they had taken refuge.

Petey: Scotty told me there was no more dope, but I guess in the middle of the night, while I was asleep, he just gave himself a shot and went out. It had to have happened early in the morning ’cause he was rock hard when I woke up. You couldn’t move a bone in his body. I hate to even think about it, man.

Lost my best friend. We depended on each other [choking with tears]. Sorry.

The initial explanation for Scotty’s death explicitly blamed law enforcement and the structural forces impinging on homelessness:

Frank: It wasn’t no O.D. Absolutely not. The guy’s too damn smart to overdose himself. It was a murder. The state killed him. They wiped out our camp and the next day he dies. He freaked out—he killed himself.

Hank: He was a little puny son-of-a-bitch, and people stepped on him. The police around here stepped on him.

Frank: The camp was destroyed by the state. [grabbing the tape recorder] Pete Wilson the governor, Frank Jordan the mayor, all the politicians are takin’ away the poor man’s money.

Hank: In one night we lost one person. The littlest man that’s been picked on before. They say good riddance, we belong in prison. We’re all homeless. They’re kicking us on the street. What are we supposed to do?

Almost immediately, however, a second version of Scotty’s death emerged. The day before his overdose, Scotty had told everyone that he had been assaulted and robbed “by the niggers” in the housing projects down the boulevard.

Felix: It was the niggers that knocked him down. Whatever happened was brought on by the beating the crack dealers gave him the day before.

The niggers knew we were gonna get kicked out and when Scotty went to buy crack that morning they beat him down. They thought they could get the whole cha cha cha right then and there. There’s no doubt in my mind it was the niggers. They took his life for a little bit of money.

Within a few more days, the Pandora’s box of interpersonal abuse burst open with the assumption—logical in the moral economy—that Scotty would have lied about the money stolen by the crack dealers in order to hide his crack binging from his running partner, Petey. Why else would Scotty have gone to the projects alone, without Petey?

After a few weeks, the polemics of interpersonal blame had fully obscured the force of the “state” invoked the day of Scotty’s death by Frank and Hank. A consensus grew that “Petey killed Scotty” by failing to revive him. Perhaps by assigning individual blame for Scotty’s death, the Edgewater homeless were able to hide their anxiety over their own everyday vulnerability to accidental overdose. In societies throughout the world, anthropologists have noted that sudden deaths caused by “bad luck” often generate accusations of witchcraft that give order to an uncertain world and also reflect preexisting patterns of interpersonal strife (Ashforth 2000; Evans-Pritchard [1937] 1976). As further proof of Petey’s malevolence, some in our network claimed that Petey had known that Scotty was dead but had left him under the blanket they shared in order to eat a free breakfast and receive a free shot of heroin from the host. Supposedly, to add insult to injury, Petey then sent their host to wake up Scotty.

The coroner’s report registered Scotty’s death as an “apparent accident” and described a physically devastated body. He was thirty-six years old, five foot seven, and weighed 115 pounds. His blood contained “morphine, codeine, ethanol, cocaine and Benzoylecgonine,” a metabolite of cocaine. He had “acute pancreatitis, an inflamed liver, edema of the lungs, and marked congestion of liver, spleen and kidneys”—painful physical conditions. In the months before his death, Scotty had been prone to “doing the tuna,” that is, convulsing spasmodically, as if he were having a seizure. His left arm had also gone limp, and he suffered from night sweats and bloody stools. He had been complaining of not being able to “get the help I need” at the county hospital. As a “hope-to-die-with-my-boots-on-dopefiend,” however, he had continued to flood his body with heroin, crack, and alcohol up to the very last moment (Pearson and Bourgois 1995).

Before meeting Scotty, Petey had been snorting methamphetamine and collecting unemployment in his hometown of Simi Valley, a conservative, white working-class suburb made famous as the venue of the trial that sparked the 1992 Los Angeles race riots, when a predominantly white jury acquitted four Los Angeles police officers of beating a black motorist, Rodney King. Petey’s wife had thrown him out for failing to support their son. Scotty, a homeless drifter from Ohio, introduced Petey to heroin, and when Scotty left for San Francisco (via Albuquerque and Santa Cruz), Petey followed.

Despite having “good veins” that were easy to locate, Petey had never learned how to inject himself. Instead, he relied on Scotty, who enjoyed lording his power over Petey, especially when Petey was dopesick. Scotty would insist on injecting himself first and would often fall into too deep a nod to proceed with Petey’s injection. Ritual subordination in the act of injection is well documented among male-female running partners and is often intertwined with romantic relations. It illustrates the kind of intimate petty brutality that is common among friends and lovers on the street and also reflects gender hierarchies (Bourgois, Prince, and Moss 2004; Epele 2002).

The physical and emotional intensity of Scotty and Petey’s relationship confused us at first. They appeared to be a gay couple, but they were living in an explicitly homophobic environment. None of the Edgewater homeless saw anything unusual about their homosocial romantic intimacy. Over the years, several other male running partnerships displayed similar levels of homosocial affection. Many of the men hugged and spooned for warmth and comfort at night. They would sometimes publicly engage in intimate mutual grooming, such as pimple popping, nursing wounds in the groin area, or cleaning soiled underwear. At the same time, almost all were explicitly homophobic. They levied the epithet “homosexual bitch” only at their worst enemies.

Petey fell apart emotionally after Scotty’s death and was unable to continue selling heroin. Felix began referring to him as “Scotty’s bitch” and calling him “baby Petey” to his face. Hank came to Petey’s rescue, treating him to heroin and offering to inject him. Soon the two men established a running partnership with even more homosocial intensity and intimacy than Petey had had with Scotty. In retrospect, we noticed in our fieldnotes that Hank had always been exceptionally kind to Petey and that Scotty appeared to have been jealous of Hank’s advances. Hank inherited eight thousand dollars from the sale of his parents’ house shortly before Scotty’s overdose and purchased a motor home, a motorcycle, and ten grams of heroin with the money. He was an especially desirable running partner at that moment, and everyone was jealous of Petey, accusing him of “sucking up” to Hank.

Hank spoke about Petey in openly romantic, almost chivalrous terms, and Petey responded appreciatively:

Hank: Early one morning after Scotty died, I came down to the corner on my motorcycle and there was Petey. He was standing on the corner against the wall, his head down, deserted by everyone. Feeling bad for him, I said, “C’mon!” And took Petey into my motor home.

Now, people out here, they don’t know Petey like I do. They pick fights with him, treat him like dirt. But I’ll slap any motherfucker upside his head with a two-by-four if they mess with Petey.

[handing Petey a five-dollar bill] Go get me a Cisco. And pick up a beer for Jeff, too.

[pausing until Petey has left the camp] So after a week in my motor home, we’re just sitting around, and Petey says, “Hank, I love you, man.” And I tell him, “Petey, I love you, too. I wouldn’t ever leave you behind.”

Initially, their relationship was framed by the other men in a discourse of masculine domination:

Carter: I saw them at it up there [pointing up the embankment]. Hank has a dick this fucking big [spreading his hands a foot apart]. Petey was on his stomach and Hank had the entire thing up inside him, just pushing, pushing, pushing. And Petey was just lying there—still.

Ben: [clarifying for Jeff] Hank’s not a homosexual. He does that just to discipline Petey, to show him who’s boss. Hank has Petey well-trained. He stands for sixteen hours at the Taco Bell drive-thru flyin’ a sign. Once he’s got enough money for a bag of dope, he won’t do anything with it. He’ll just go look for Hank so that they can go fix together. Once in a while, maybe, Petey’ll go get himself a Cisco. But Hank has him running scared.

Carter: Yeah, I leave in the morning to go hit a lick, and when I return after dark, Petey’s still out there flying his sign at the same spot.

Eventually, however, disrespect for Petey dissipated, and the two men were reintegrated into the scene as long-term running partners similar to any other stable duo who contribute effectively to the moral economy of sharing.

In The History of Sexuality, a book that redefined the field of sexuality studies, Foucault argued that sexually defined subjectivities (heterosexuality, homosexuality, queer identity, and so on), whether considered “normal” or taboo, are not the product of a set of “natural” inclinations. Sodomy, for example, was “an utterly confused category” in the Middle Ages (Foucault 1978:101). Not until the late nineteenth century, with the emergence of biopower, were sex and romantic love between men defined as a perversion. The specific subjectivity of male homosexuality developed out of “the reciprocal effects of power and knowledge” to become “a quality of sexual sensibility . . . a hermaphrodism of the soul . . . a species” (Foucault 1978:43, 101; see also D’Emilio 1983; Rubin 1984).

Historians have argued that gay identity in the United States emerged after World War II. Formerly, men who had sex with one another might maintain a fully masculine social identity (Chauncey 1994). In fact, sex between men was relatively common in the largely all-male communities of the marginal lumpenized working class. Among hobos and tramps in the 1910s and 1920s, there was a linguistic term, jocker, for older, aggressive men who dominated younger males sexually (DePastino 2003:85–91), but the word had no implication of a “gay” identification.

In the 2000s, these same “pre-gay” patterns persisted. Lumpen and poor working-class men might, under certain conditions, have sex and fall in love with one another without altering their masculine self-conception. They could even remain aggressively homophobic. Sex between men who do not self-identify as gay or bisexual has been well documented in a range of contemporary lumpen settings, such as prisons (Donaldson 2004; Schifter 1999; Wooden and Parker 1982), sex worker strolls (see review by Kaye 2003), and transient labor camps (Bletzer 1995). Although it is frequently described, this form of masculine sexuality remains undertheorized, and it is not generally analyzed as a class-based phenomenon. It is often presented as an ambiguous cultural phenomenon or is framed as the domination of one participant by the other. For example, the literature on Latin American and circum-Mediterranean masculinities distinguishes “passives” from “actives” in the sex act (Brandes 1980; Cáceres and Rosasco 2000; Faubion 1993; Lancaster 1992; Padilla, Vasquez del Aguila, and Parker 2006; for an example of portrayals in the U.S. press of African-American “down low” scenes, see New York Times Magazine 2003, August 3).

The men on Edgewater Boulevard engaged in romantic and affectionate displays with one another without interpreting these practices to be identity markers signaling a transgressive sexuality. Their sexual flexibility offers another window on the uneven effects of biopower among the lumpen, who have not internalized the exclusive distinctions between homosexual and heterosexual subjectivities that have prevailed since World War II in the middle and upper classes and, to a lesser extent, in the stable working class.

If lumpen is a subjectivity as much as a class category, it can be understood as emerging out of a negative relationship both to the mode of production and to biopower. We might expect, consequently, that lumpenized populations would have more transgressive ways of being in the world than normatively disciplined citizens for whom biopower is generally productive and rewarding. The same effects of governmentality that give rise to the phenomenon of the righteous dopefiend might be what allow the Edgewater homeless to find no contradiction between homophobia and homosexual-like relationships. Similarly, this understanding of lumpenized subjectivities helps contextualize our discussion in the previous chapter of how men can remain resolutely patriarchal despite having no sense of normative responsibility for maintaining their children economically, and why middle-class rules concerning the scope of the incest taboo did not prevent Al from talking triumphantly about having a son with his sixteen-year-old stepdaughter or being offered the sexual services of his daughter-in-law by his son.

Within the field of sexuality studies, an approach known as queer theory dedicates itself to theorizing and documenting transgressive sexualities (Seidman 1996; Spargo 1999). Class dynamics have been, for the most part, absent from this body of literature. Queer theory is heavily influenced by Foucault, who, except in publications written during the radical political ferment of the post-1968 decade (Paras 2006; Foucault 1975), generally avoided using social class as an explicit category in his analysis of power. Foucault came of age at the height of the Cold War and was reacting against the stultifying shadow of the French Communist Party’s Stalinism on marxism in France (Turner 2000:45–46). Nevertheless, despite his rejection of “grand narratives” and economic functionalism, Foucault was deeply influenced by marxist critique, and this explains the passion with which he theorized the effects of power across history (see Foucault 1975:33; Foucault [1981b] 1991). Unfortunately, as noted in the introduction, many readers in the United States, unlike many European readers (see, for example, De Giorgi 2006; Garland 1997:204–205, 209 n29), interpret Foucault’s theory as being antithetical to marxism and class analysis. Recognizing that class is a crucial manifestation of power-effects as well as a relay of power in the constitution of subjectivities, however, helps explain the phenomenon of lumpen male love.

During the first few weeks of their new relationship, Hank and Petey drove up and down the California coast and spent the last of Hank’s inheritance. Their honeymoon was cut short when Hank’s license was revoked for a “driving under the influence” violation and his motor home was impounded. They took refuge in a new “white camp” that had been reestablished behind the Dockside Bar & Grill.

Hank built a weatherproof compound with multiple layers of privacy. He pitched his old red pup tent inside an oversized family tent, which he surrounded with a plywood wall nailed to the sides of upright pallets. He then covered the entire construction with blue plastic tarps. Levolor blinds marked the entrance, opening and closing on a still-functional drawstring. The interior of this shelter simulated a one-bedroom apartment, complete with separate living room and bedroom. Later, Hank added a kind of foyer, an outdoor sitting space raised from the mud by wooden pallets covered by carpet remnants. Three yards behind this structure, just beyond a clothesline stretched across a clearing in the brush, Hank built a “bathroom,” using a two-by-four wooden frame with white polyester sheets tacked on for privacy. The toilet consisted of a metal platform seat for the disabled perched over a five-gallon paint bucket. By the smell and sight of feces scattered around the perimeter of the camp, it was evident that few people used the outhouse.

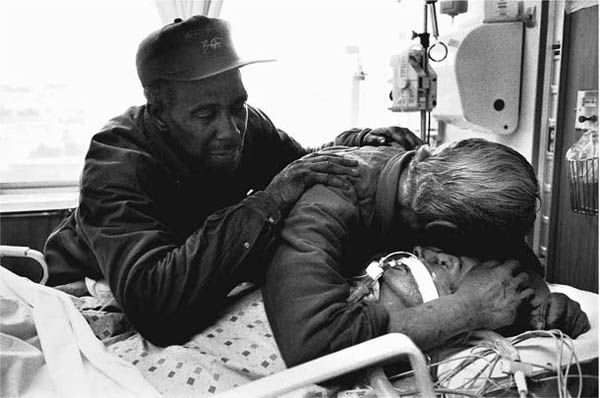

Hank decorated their new home with the symbols of bourgeois domesticity. Soon they had two easy chairs, an upright vacuum cleaner, a golf bag, and Christmas decorations dangling from the branch of an overhanging scrub oak. Hank also framed and hung a group photo Jeff had taken of their Thanksgiving barbecue, positioning it as if it were on the mantle of a fireplace. As a final touch, in the place of honor Hank posted a regulation-size American flag.

Hank’s reputation for generosity attracted a wide network of former acquaintances, and his shelter soon became a center of social life. Many of the “friends” passing through were newly released from prison. They represented the human fallout from the dysfunctional bureaucracy of the California Department of Corrections’ parole violations system. Between 1980 and 2003, the proportion of reincarcerated prisoners in California increased almost threefold as a result of stringent new statutes regulating technical parole violations (New York Times 2003, November 14; State of California, Little Hoover Commission 2003). California began reincarcerating 67 percent of all parolees—twice the national average. Most of the parole violators we met in Hank’s camp were sent back to jail without trial for “giving dirty urines” to their parole officers on random drug tests. On one occasion, Jeff slept in Hank’s “foyer” next to a man called Crazy Carl, who had just been released from prison.

We wake up drenched by the fog and I nestle under the covers Hank gave me for another half hour, feeling cozy despite the morning chill. Crazy Carl, however, lying on a broken-down La-Z-Boy, is having a very different experience: “I’m scared. I’m scared,” he keeps whispering to himself, his eyes bugging with genuine fear. “I hate waking up! Another day that I’m broke. I don’t know how I’m gonna stay well. I don’t want to go back to jail, but I got to get well.”

Mistaking my look of concern for anger, he begins apologizing profusely and then apologizes for apologizing. I reassure him, to no avail.

It is now 5:30 A.M. Petey emerges from the tent, his head hung low, a squeegee and a bottle of Windex tucked under his right arm and his cardboard sign, WILL WORK FOR FOOD, dangling from his left hand. Hank has already gone to meet the dealer at the pay phone on the corner, having sold a television set he scavenged from a dumpster during the night.

Upon his return, Hank offers Crazy Carl a taste of his wake-up shot of heroin to decrease his rising panic level. Crazy Carl asks Hank to inject him in his jugular. He is scared that if he muscles, he might get an abscess and be “violated” by his parole officer. He also has to borrow Hank’s needle because his “warrantless search condition,” which allows the police to search him on sight and without probable cause, makes it too risky for him to carry a syringe.

A few minutes later, Crazy Carl’s anti-psychotic medication is mixing badly with the heroin, and he is staggering around the camp, his eyes rolling back into his head. “I’m fine. I’m fine. It’s just my meds.” When he falls and begins “fish-flopping,” we drag him onto a mattress. I run to call an ambulance, but they stop me, worried about the police.

Luckily, Bonnie, one of Crazy Carl’s former running partners, walks into the camp at this moment and announces that she is going to call 9-1-1. This prompts Crazy Carl to stumble back to his feet and sprint out onto Edgewater Boulevard. We run after him, but he has disappeared. Seeing our alarm, the attendant in the gas station across the boulevard points to a two-foot-high shrub next to the air hose. Crazy Carl, in a crouch and still trembling with his head in his hands, is trying to hide, but with the effectiveness of an ostrich putting its head under the sand.

We surround the shrub to guard Crazy Carl until the ambulance finally arrives. He refuses to stand up until the paramedic promises not to call the police, because that would automatically trigger a parole violation.

Within a month, Crazy Carl was reimprisoned for failing a routine urine test. We saw him a half dozen more times over the years, but we never got to know him well because he never stayed out of custody for longer than a few weeks. Carl is an example of a “dual-diagnosis” addict whose medical problems were being handled punitively in the criminal justice system rather than by public health services. Not all of the peripheral people cycling through the revolving door of California’s parole violation system into Hank’s camp were as harmless, or as clearly mentally ill, as Crazy Carl. Some, like Little Vic, described in chapter 1, were scary. This was also true of Leo, another newly released prisoner who moved into Hank and Petey’s tent and began bullying all of us incessantly. To everyone’s relief, he was “violated” within a few days.

Felix: The cops got Leo last night. They came in blazing after dark. The whole bit, police, parole agents, the Special Security Unit . . . all their motherfuckin’ lights flashing like they’re filmin’ a movie. You couldn’t even fuckin’ twitch, blink, fart, move—nothing!—without them seeing every fuckin’ thing.

Leo was out taking a pee. When he seen the lights coming up the hill, he went into the bushes. But he couldn’t make it far because he was barefooted.

Leo’s gone. They caught two of his partners and they snitched on him. He’s a two-striker, and they got a case on him of armed robbery and home invasion.

Now we’re fucked because he’s brought the cops on us. They warned us, “We’ll be back every time there’s a parolee at large.”

Ironically, as we saw in chapter 1 with Little Vic’s violent assault, one of the many unintended consequences of the bureaucratic logic of California’s parole system during these years was to process arrests for violent crimes as routine parole violations rather than as new crimes. Consequently, only four months later, Leo was back in the camp intimidating all of us. On this second parole release, however, fifty-two-year-old Leo lasted only three hours free on the street before dying of an aneurysm while smoking crack in Hank and Petey’s tent. As with Scotty’s overdose, Leo’s death precipitated a gray zone polemic of interpersonal blame.

Felix: Leo was a no-good snitch. How else could he have gotten out of jail in four months? He was a third-striker.

Carter: Leo was flashing a roll of cash, over two grand.

Tina: I think Hank took Leo’s money. Petey didn’t work for two fuckin’ whole days after Leo died.

Carter: They rolled his body. I would have rolled him, too, before the cops took it. Leo ain’t gonna be spendin’ that shit.

An explicitly sexualized rumor was added to the mix, alleging that Leo had been receiving a massage from both his uncle and Petey in the pup tent at the moment of his death.

The sudden death of an acquaintance or friend is merely one of the many crises that engulf the Edgewater homeless virtually every day and produce a chronic state of emergency normalizing conflictive relations. Leo was quickly forgotten, overshadowed by the actions of law enforcement, the most pervasive destabilizing force in the lives of people on the street.

In 1996, Willie Brown, a machine Democrat, was inaugurated as mayor of San Francisco. The conservative Republican governor of the state, Pete Wilson, was determined to upstage Brown, and the homeless became pawns of yet one more of the many get-tough-on-crime political media campaigns that rocked the 1990s. The governor ordered Caltrans, an agency he controlled through the state’s Department of Transportation, to evict all the homeless living on state-owned “public land” within the San Francisco city limits. Newspapers published front-page stories with battlefield-style maps peppered with red dots to indicate the locations of targeted homeless encampments throughout the city (San Francisco Examiner 1997, March 26). The San Francisco Examiner (1997, March 31) conducted a telephone survey asking, “Should the homeless be allowed to live under the freeways?” and 67 percent of the respondents (more than one thousand residents) responded “No.”

Hank and Petey’s encampment was identified by Caltrans officials as one of “the largest concentration[s] of homeless of any of the Caltrans sites” (San Francisco Examiner 1997, March 26). The nightly news on local television featured human interest stories of disheveled men, huddled around garbage bags and shopping carts, poised to flee. One of the segments included a twenty-second sound bite of Hank with Caltrans bulldozers behind him, confabulating that the state was evicting “defenseless women and children” from his camp.

The public debate on San Francisco’s homeless policy during these years offers an example of the micropolitics of governmentality in action. The soft left hand of the state, in the form of public health and social services, was jockeying with the hard right fist of law enforcement, and the interplay between these positive and negative manifestations of biopower became especially perverse. The first salvo was fired by the city’s new district attorney when he dropped 39,020 citations and bench warrants for the seven “quality of life” violations targeted under the previous mayor’s Matrix Program (San Francisco Chronicle 1996, April 17). The new mayor, Willie Brown, also unveiled a “comprehensive homeless services program” to address “root causes” of the problem. In response, the governor tried to justify evicting the homeless from Caltrans property by declaring their encampments “public health hazards.” The mayor parried that the governor was disrupting his new service programs. At the last minute, the Department of Transportation compromised by agreeing to desist from evicting those encampments that complied with minimal sanitary standards. The Coalition for the Homeless, a left-wing grassroots organization, mobilized a cleanup campaign in the camps, and the city offered to supply portable toilets (San Francisco Examiner 1997, March 26).

Eager to support the public health side, we naively mobilized with the white members of the Edgewater homeless to join the coalition’s cleanup initiative. The encampments at this time were still fully segregated, and the African-Americans expressed no interest in getting involved.

The city sanitation department has provided the guys with dumpsters, garbage bags (emblazoned with the state cleanup logo “Care for California”), shovels, rakes, gloves, hard hats, dust masks, and white hazmat [hazardous materials] suits. One of the coalition staff members comes by for a site visit while I am helping Felix and Hank lift a charred box spring mattress into the dumpster. The guys are excited by the cleanup campaign and have put in a full day of work. Even the toilet area is nearly spotless.

Two weeks later, the California Highway Patrol tacked an official twenty-four-hour Notice to Vacate sign onto the “mantelpiece” tree by Hank’s flagpole. The following day, a Caltrans work team arrived, flanked by two Highway Patrol officers and trailed by television cameras. Hank and Felix donned hard hats for the occasion, and Hank also wore a San Francisco Fire Department sweatshirt, but their attire won them no sympathy. One of the Caltrans workers found a syringe full of heroin in the dirt by Max’s tent. At the request of the television reporters, he held it up with his metal “debris nabber” for the cameras. Oblivious to the media circus, Max sighed that he wished he had found the syringe.

By early afternoon, all the shelters had been razed, and all the possessions had been churned up in the garbage trucks. To add insult to injury, one of the Caltrans workers joked, “The homeless did a good job cleaning. There wasn’t much left for us to do.” Several other Caltrans workers, however, expressed empathy for the homeless: “We’re in bridgework. We’ve been torn from our trained positions. I know what these guys are going through. Hell, I’m just two paychecks away from being here myself.”

Over the next several months, Caltrans returned several more times with teams of prison laborers from San Quentin to clear-cut the trees along the embankment. They arrived with chain saws, pitchforks, and prefabricated Cyclone fences topped with barbed wire. When Jeff attempted to photograph, the supervisor admonished, “If you don’t stop taking pictures of my men, they will be punished.” The crews left vegetation only on the steepest parts of the embankment, assuming that no one could possibly live there. Those became the spots where the Edgewater homeless carved out, once again, a precarious niche. Noting the persistence of the homeless colony, several of the local business owners paid Hank, Felix, and Carter twenty dollars each to cut down the remaining pockets of brush. They were eager to earn the money: “If we don’t do it, someone else will.” In short, they definitively reevicted themselves from the embankment for enough money to buy their next bag of heroin. What originally had been a thickly overgrown two-mile-long hillside was now an eroding hillside, fully exposed to surveillance from the freeway above and the boulevard below.

At the time of this eviction, the dot-com boom was gathering momentum, and Mayor Brown, attuned to the neoliberal tide of the era, reversed the priorities of his policies to reduce homelessness. He reinstituted a law enforcement campaign following the zero-tolerance model of his predecessor. The San Francisco police even requested that the neighboring Oakland Police Department lend them its Argus helicopter, “equipped with special heat-detecting technology, known as forward-looking infrared” for nighttime detection of homeless encampments in Golden Gate Park (San Francisco Chronicle 1997, November 8). Moving anxiously from temporary site to temporary site, the Edgewater homeless lost most of their blankets and sleeping bags, all of their tents and tarps, most of their needles, as well as all of their contact with the Department of Public Health’s mobile health van.

At the time, syringe possession was a misdemeanor, but the local precinct captain directed his officers to issue felony charges of “possession of controlled paraphernalia with intent to sell” to anyone carrying more than two needles. Fearing police reprisals, the city’s needle exchange activists began enforcing their program’s official one-for-one syringe exchange policy. As a result, the Edgewater homeless did not dare carry more than a few needles, and they stopped regularly visiting the needle exchanges that formerly had been their primary source of clean needles—as well as their gateway to treatment and primary care services. As Frank explained when we asked why he no longer went to the needle exchange: “Maybe you ain’t got a dollar to catch a bus across town to get to the exchange. It just ain’t worth it for a couple of needles, especially if you’re feeling sick.”

For the remaining half dozen years that we followed the Edgewater homeless, they were not able to maintain large, stable camps for more than a few weeks before being evicted. This instability reduced their access to outreach services, but the numbers of people living along the boulevard did not diminish. They shifted their shelter strategy and began seeking semi-functional and abandoned parked vehicles in which to sleep. The transition was difficult for everyone, but it was particularly hard on Hank and Petey. During the six months following the Caltrans offensive, all the whites were hospitalized for abscesses. Interpersonal relationships in the network deteriorated as daily life became even more precarious and isolated. Hank and Petey oscillated between nurturing one another tenderly and squabbling bitterly.

Using sash rope scavenged from the dumpster of the window company, Hank has strung a web of blue plastic tarp hammocks under one of the few remaining thickets of scrawny pines that Caltrans left to prevent erosion. The Highway Patrol has forced Hank and Petey to move six times in the past three weeks, and the hammocks can be disassembled and packed at a moment’s notice. To camouflage their access path (and to slow the police down), Hank has replaced the Caltrans padlock on the gate of the new Cyclone fence with a lock of his own.

They feel stable enough to invite me to spend the night, and Hank strings up a newly woven hammock for me. An infected abscess on his rear makes him unable to support his full weight. He has a cane, but his leg quivers nonstop.

During the last eviction, Caltrans had confiscated Hank’s medical kit, including the scissors he used to lance his abscesses. Frustrated and in pain, he tears a piece of aluminum from a crushed soda can and presses the jagged edge into the side of the abscess.

“Hank, stop! Let me take you to the hospital.”

“Jeff, in battle, if there is a bullet lodged in your body, you just take care of it.”

I remind Hank that this is not battle. He nods his head and admits, “I haven’t showered in over thirty days, Jeff. I’m too ashamed to go see a doctor.”

Petey rolls out of his hammock and walks up behind Hank. Kneeling, he helps squeeze the sides of the abscess on Hank’s left buttock, leaving his comic book open on the ground so that he can continue reading in between squeezes.

Half an hour later, Hank is grumbling that he was not able to get “the core” out of his abscess and that it still “hurts like hell.” I can see he is very upset because this pain will prevent him from working tomorrow. For the past several months, Andy the mover’s jobs have been his primary source of income. A few weeks ago, he cracked a disk in his lower back “lifting a grand piano” on a job. The doctors in the county hospital emergency room gave him a cane and ordered him to stop lifting heavy weights. Hank, however, hung onto Andy’s moving jobs for a few more weeks, until he could no longer stand the pain: “I’m just not up to it anymore.” The duo, consequently, has become completely dependent on Petey’s panhandling to support their habits. Although still publicly subordinate in the relationship, Petey is now insisting on injecting more than Hank since he generates most of the money, causing tension.

Hank rummages through a pile of dirty clothing for a syringe. He finally finds one and, frowning, puts his ear to the chamber to listen for a hole as he runs the plunger up and down the barrel. “Shit! It’s cracked.” When Petey tells him he does not have a needle, Hank flies into a rage.

Hank: “Goddamned liar! [turns to me] I’ve had enough of Petey; he drags us both down.”

Petey: “I’m sorry, Hank. I’m sorry.”

Hank: [shouting] “If you could slap the shit out of me, you’d do it.”

Petey: “No, I couldn’t. I don’t have it in me, Hank. Like you said, I’m too passive.”

Hank: “Oh, boy! I never should use those words around you.”

Hank attempts to stomp out of the camp but can only limp because of his abscess and back pain. When he reaches the chain-link fence, he hands me his cane and struggles to climb over. Seeing that this is going to take a while, I hop the fence to stand lookout for the police, who drive past here on their way to the neighborhood up the hill.

Hank buys a Cisco at the corner store. For a couple of hours we watch the crack dealing on the corner increase in tempo as night falls.

When we return to the camp, Petey is already asleep in his hammock. Hank immediately complains that Petey goes to bed too early. “He should be out right now flying his sign. We don’t have anything for tomorrow’s fix. He didn’t go to sleep sick, but I will. I know he’s doing things behind my back. He probably fixed while we were out.”

Hank smokes a cigarette, and I lie down in my hammock. Light from the Lotto billboard above the highway is reflecting softly through the foliage, and when I close my eyes, the smell of the eucalyptus trees almost masks the diesel fumes.

Hank comments, “The freeway is not too bad here. This is all you hear: whoosh, whoosh, whoosh. Down where Felix stays, the traffic makes a terrible noise. There’s a bump down there and the cars hit it, and it’s loud.”

Indeed, the creosote railroad ties that support the embankment at this spot muffle the sound of the cars speeding by on the freeway next to us. It is an almost soothing murmur, like the ocean lapping on a nearby shore.

I drift to sleep watching rats scuttle about the branches above my head and barely hear Hank mutter: “Gotta get a cat in here.”

As the night progresses, Hank’s dopesickness worsens. I am awakened several times, at first by his tossing and turning and later by his sighing and cursing. Occasionally, he gets out of his hammock to pace. At one point, I awaken to the sound of rustling and see Hank crouching on the ground by Petey’s hammock, his head in his hands. But he becomes silent as though hiding, and a minute later he returns to his hammock.

Around 2:00 A.M., a Caltrans road crew begins jack-hammering on the freeway above. They sound like they are only a foot away. The voice of a foreman is audible above the hubbub. One of the workers is complaining: “Where the fuck is Jeff? He said he’d meet us here.” I feel a twinge of paranoia. Luckily, we are too well camouflaged for them to notice us from over the edge of the freeway.

Petey is the first to rise in the morning. He has slept with his boots on—big jackboots that Hank picked up on a moving job last week. Before heading down Edgewater straight to the Taco Bell drive-thru to fly his sign all day, I see him carefully, out of Hank’s sight, hiding two syringes in a hole in the quilt lining of his shirt.

Hank and I enter the Taco Bell, where Hank has to pay only twenty-seven cents for a cup of coffee, the senior citizen discount. He asks me if I saw Petey wake up in the middle of the night to fix. I shake my head no, but this does not assuage him. His nose is dripping from dopesickness and he is hunched over and shaking: “It’s the second time that I’ve caught him. I’m gonna leave him behind. He doesn’t carry his own weight. I’m ready to cut him loose. I’m beyond hurt. I’m angry now.”

I can see Petey shivering outside as Hank and I sip our warm coffee inside, and I wonder if Hank is becoming delusional. An hour and a half later, Petey signals to Hank that he has enough money for a bag. As we are walking to the copping corner, Hank launches into yet another furious tirade at Petey for “doin’ things behind my back . . . never helping me out or even pulling your share.”

Petey breaks through Hank’s diatribe by asking in a soft voice, “Hank . . . Hank . . . Tell me, Hank; who else is my friend? Tell me . . . who else is my friend?”

This soothes Hank, who responds in an almost reassuring tone, “Well . . . Jeff is your friend.”

Petey: “No, Hank. Who’s my friend every day?”

Hank: [softly] “But what are we going to do when I wake up sick again tomorrow morning?”

Petey: [gently and slowly] “I’ll do my best, Hank. I’ll go back out there with my sign. [turning to me] Things have been bad, Jeff. It’s been raining so hard that no one wants to take the time to dip into their pocket to give me a nickel or a dime. They don’t even wanna crack their window open.”

Petey notices me looking at his teeth in alarm. The gums have rotted black. He points to the three or four twisted teeth on the bottom half of his mouth. “I need to get these pulled.” His gums have been bleeding, and he thinks this might be why, for the past week, he has been throwing up when he wakes up. I offer to drive him to the homeless clinic, but he shakes his head, gesturing toward the corner where Sal is selling heroin.

Over the next few weeks Petey’s health continued to deteriorate with bleeding gums, chronic vomiting, and incessant shivering. Hank’s Vietnam references also became increasingly vivid. On one occasion, Jeff found Hank behind the A&C corner store in the throes of a PTSD panic attack.

Hank is sobbing so hard he has to grip the chain-link fence to keep from falling. Moaning, he explains that he is looking for Petey, who is “AWOL” from his usual panhandling spot by the exit sign at the Taco Bell drive-thru. “I just know it. I can feel it. I know my Petey. He’s gone to the hole. I told him . . . I warned him never to fix alone. He’s dead!” Heaving from the sobs, Hank doubles over as if he were about to vomit. He then straightens himself up, shouting, “I won’t leave a man behind! I’ll carry him home, on my shoulder back to the corner. It’s just not right to die in a place like that.” And he begins marching down the boulevard.

Luckily, Petey arrived in the midst of this outburst. “Calm down, Hank. I didn’t go anywhere. I was panhandling behind the McDonald’s all day.” Flashing a quarter-gram bag of heroin in his open palm, Petey added softly, “I got you a fix. Everything’s okay. You’re not in Vietnam.” Hank spread his arms. Oblivious to the pedestrians passing by, they embraced in a deep bear hug for several minutes, nestling their faces in the crook of one another’s neck, Petey stroking the crown of Hank’s head and whispering, “It’s okay. It’s okay.” Hank continued sobbing, but now with relief.

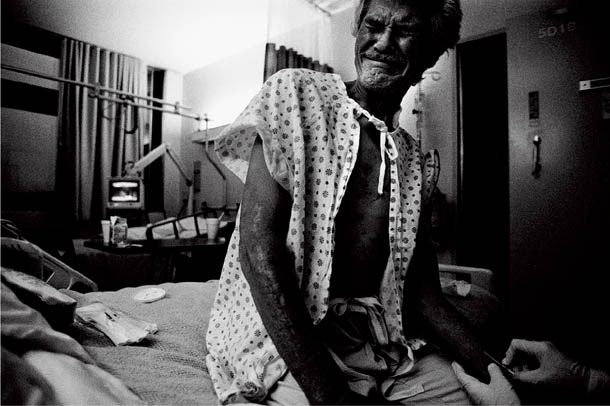

Over the next year, Hank became a frequent flyer in the county hospital’s emergency room, with over a half dozen long-term admissions. First his back condition became compounded by double pneumonia; then came a diagnosis of colon cancer, followed by radiation therapy. Soon he was also complaining of mysterious seizures that he called mini-strokes. We assumed that these were either delirium tremens from alcohol or a confabulation. The seizures, however, were accompanied by spiking fevers that the doctors could not diagnose. Hank claimed that they had found a rare virus in his spine and that there were only two other known cases in the world, “both men my age who were also in Quang Tri province [Vietnam] in 1970.” The county hospital deployed its expensive, state-of-the-art technology (electrocardiograms, computerized axial tomographies, magnetic resonance imaging, biopsies, and innumerable blood tests) but was not equipped to address the social context for Hank’s physical distress, and he became a disruptive, “nonadherent” patient. Most of Hank’s hospital stays lasted two to six weeks, long enough to control his fever and get him standing once again.

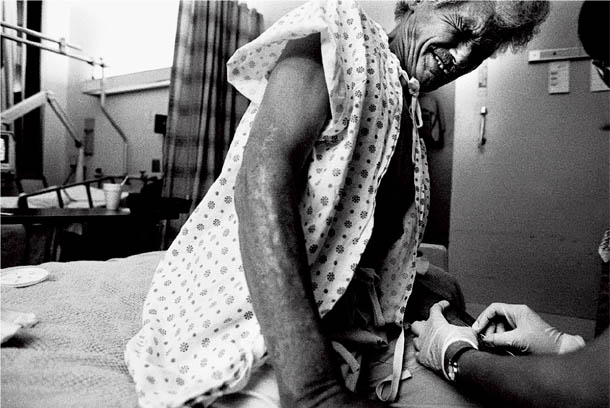

Hank was often undermedicated for heroin withdrawal symptoms during his hospitalizations. When we visited him, we would usually find him semi-conscious, moaning in pain, or alert and wincing, gripping the side of his mattress:

The nurse screwed up my medication again. She only gave me twenty ccs of morphine. That won’t do anything for me. It’s like a ten-dollar bag. If I was out on the street with this pain, I’d shoot myself. I wouldn’t put my worst enemy through this. Finally, she agreed to speak to the doctor and she apologized. I get eighty ccs now.

It was an ordeal to draw blood for tests and administer intravenous medications. The IV needle would bend as it hit the scarred tissue in his forearm. Most nurses would give up and call a doctor to insert the IV in Hank’s jugular with local anesthetic. Only doctors were allowed to perform this procedure at the county hospital, prompting Hank to chuckle, “Jeff, you should show these people those pictures of me hitting Sonny and Crazy Carl in the neck.”

The doctors suspected that a fungus resistant to antibiotics had cracked the disk in Hank’s lower back. They feared it might be spreading to the neighboring disks, and they proposed a surgical intervention. They did not, as usual, discuss with Hank the surgery’s potential effects on his chances of surviving on the street:

[whispering] I can’t understand what the doctors tell me. I’m confused all the time. Do you think the medication might be messing with my head? I think the doctor said there’s a fifty-fifty chance I might end up crippled. Jeff . . . ? Do you think I’ll survive for even one day under that freeway as a cripple?

Meanwhile, Caltrans’s evictions continued unabated, and Petey lost all their blankets during one of Hank’s hospitalizations: “They didn’t even put up no warning signs or nothing. I hope it’s not cold tonight.” For several nights, Petey managed to sleep undetected in Hank’s room. Hank hooked his IV antibiotic-morphine drip into Petey’s arm and ratcheted up the dial, “so that Petey can work for Andy tomorrow.” On one occasion, a nurse forgot a bag of medication. “Look what she left! The morphine! Quick, Petey, hide it in the bathroom.” This stroke of luck allowed Petey to stay by Hank’s side for a full forty-eight hours without having to panhandle in the rain at the Taco Bell drive-thru or move furniture for Andy. In a last ditch attempt to prevent surgery, the doctors intensified Hank’s antibiotic regimen. The nurses had to change his IV drip every hour and a half throughout the night, and they caught Petey sleeping in the easy chair. He was immediately evicted and sent out into the rain with no blankets at 2:00 A.M.

Two weeks later, Hank was back out on the street, nodding and swaying on his feet. With Hank’s permission, we asked the physician on our ethnographic team to consult Hank’s medical record from the past sixteen months. According to Hank’s file, the neurologists originally thought the seizures were caused by “localized lesions in his brain” but could not locate them on a CAT scan. His repeated “spikes of fever” suggested an infection and were diagnosed as an “empyema”—a brain abscess. They conducted a lumbar puncture to test his cerebral spinal fluid and also found meningitis. They prepared to conduct brain surgery to drain the pus from his brain, but he had, meanwhile, responded well to an aggressive new regimen of triple-therapy antibiotics. This was what prompted the hospital to release him back to the street with instructions to take his antibiotic cocktail orally (ampicillin, vancomycin, and ceftriaxone). Hank’s official discharge papers stated: “psoasmyositis and lumbar osteomyelitis and clostridium bacteria, copd L2–3 and L4–5 disc protrusion.”

Three days later, the police confiscated Hank’s medications.

Hank: There was nothin’ I could do. They see my pill bottles and see my name all over it. They even spread my pills over the hood of their car, taking their pictures like they’re somethin’ illegal.

I asked him, “Can I have my medication?”

They told me, “No. This is evidence. We think you are dispensing drugs here.”

“What do you mean dispensing drugs? It’s got my name on the bottle!”

“Then why do you have it hidden here on state property?”

“So no one will steal it. This is my safe spot in the woods. Do you expect me to carry all these pills?”

Jesus Christ! I went to Vietnam. I deserve better. I got shot up, Philippe, four fuckin’ times. I was in a bomb blast. I fell out of a helicopter, and I fell out of an LST [Landing Ship Tank]. The LST wasn’t an accident. I got thrown outta that troop transport. . . .

Jeff: Let’s go to the hospital right now. Better yet, I’ll call an ambulance for you so you don’t have to wait five hours in triage.

Hank: Why? So they can send me right back out again?

Petey was still vomiting blood when he woke up each morning and was now severely underweight. With infected sores on his feet and aches in his legs, it was getting harder for him to stand panhandling with his sign for so many hours on end. Formerly the object of scorn among the Edgewater homeless, he now elicited pity. The women and the African-American men, who had formerly refused to have anything to do with Petey, started helping him.

I walk in on Felix, Ben, Sonny, and Hank fixing in the shack in the back alley. While they each muscle into their rears, Ben says, to no one in particular, “I saw Petey shitting in here last week.”

Hank: “My Petey?”

Ben: [pointing his chin at a soiled pair of long johns in the corner] “That’s Petey’s job.”

Felix: “He was in here yesterday looking to pound the dirty cottons.”

Sonny: “He looks terrible, Hank. Ready to drop.” [sucking his face in to make his cheeks concave]

Hank: “It’s the alcohol. He’s drinking too much. I’m gonna have to start force-feeding him—gotta get milk and nutrients in him, wheat germ. I’ll use our wake-up fix money for food if I have to.”

We hear persistent honking outside, and Hank runs out. It is Andy, the mover. Hank is supposed to go to the hospital for his weekly radiation therapy for his colon cancer this morning, but instead he is going to work for Andy, who assures him there will be no pianos to carry in today’s job.

I walk with Ben down the boulevard to where Tina is sitting in the sun with Spider-Bite Lou on a sliver of grass in front of the Taco Bell. The two have been binging on crack together and are drunk, sipping malt liquor out of a plastic water bottle with a squirt tip. Tina is applying eyeliner and lipstick, and Spider-Bite Lou is scratching at the scab on the back of his neck. The tops of his hands and his upper lip are covered by crusty yellow sores from a newly infected case of impetigo. Ben and I join them, to warm ourselves in the sun. We watch to see if Petey is having any luck flying his sign at his usual spot. Hank has scribbled PETEY’S SPOT in black magic marker on the back of the exit sign at the Taco Bell drive-thru.

Tina tells me that the police arrested Petey for panhandling yesterday and found three used syringes in his pocket. They charged him with selling syringes, and he has a September 10 court date. With sympathy, she adds, “And his GA [General Assistance welfare check] was cut off this month for missing his appointment.”

Ben: [muttering] “Petey’d give someone a blow job with bad breath!”

Lou: “Fuckin’ pussy!”

Tina: “Be nice! He’s sick.”

Ben: “He’s probably got that hep C.”

Tina: “Shit! We all got it.”

Noticing us looking at him, Petey walks over to say hello. He looks older than he did just a few days ago, new lines etched into his gaunt cheeks. Ben shoos Petey away before he can sit down: “No one invited you over.” Petey leaves in a huff. Ben resents Petey because Nickie, worried for Petey’s health, has invited both him and Hank to stay over for a few nights in her apartment, where Ben has been living for the past few months.

Petey, ten feet away from us, grimacing with his emaciated face covered with open sores, suddenly throws his hat and sign onto the sidewalk. He is crying, uncontrollably.

Tina runs over and takes him into her arms. “Ben hurt your feelings. Don’t worry, Ben was only joking.”

I follow suit, hugging and reassuring Petey. Through his tears, he moans that he is dopesick, “and I’m tired of all this shit [pointing to Ben and Lou]. And I don’t know where Hank is. He is supposed to have been back from working with Andy by now.”

Leading me gently by the elbow a few steps down the block, Tina whispers: “This boy needs to eat. I been givin’ him burgers. He’ll eat it while you watch, but the second you turn your head . . . he throws it to the pigeons. Can you help him out, Jeff? Lou been takin’ his money. Hank saying he going to hit Lou with his cane. I told him, ‘You go back to the hospital, Hank. I’ll take care of Lou. Don’t you worry.’ ”

Shaking her head sadly, she adds, “Petey can’t take care of hisself. That’s a shame.”

I hand Petey four dollars, and Tina grabs one of them, kissing me on the cheek, “Thank you, Jeff. Love you!” She runs off to catch the bus to Third Street to buy crack and blows us kisses through the window.

Shifting his weight from foot to foot to ease the ache, Petey gags and heaves a mouthful of blood into the gutter.

Jeff: “Petey, let me take you to the hospital right now.”

Petey: “I’ll go next week after I pick up my hep C results. I promise, Jeff.”

There is no arguing with him. A public health research project is paying drug injectors fifteen dollars to pick up their hepatitis C test results and be counseled. Petey will not forego that guaranteed income, regardless of his health.

I ask Petey about his arrest yesterday for panhandling. He blames himself for provoking the officers. They had asked him if he had “points [syringes]” on him before searching him.

Petey: “When cops reach into your pocket and find a rig [syringe], after you’ve said no, they fuck with you. He cuffed me. I was scared, but he didn’t take me in because of the sores on my face. I told him I also had abscesses. [smiling] He told me, ‘I don’t want to have to wait all day for you at the hospital.’ ”

As a result of a lawsuit, a new directive has been imposed on the police that mandates treatment for all arrestees suffering from abscesses—another example of the conflictive interface between law enforcement and public health.

Petey suddenly falls silent. When I ask him if he is okay, he starts talking about how much Hank’s colon cancer scares him. Then, in the middle of the Taco Bell parking lot, with the afternoon sun beating down, Petey unsuccessfully tries to hold back a new round of tears, his fingers pinching at his eye sockets, his chest heaving.

Carter and Vernon have walked over and the three of us stand frozen, surprised by the sudden emotion. Carter breaks the ice by embracing Petey: “Everything’ll be all right.”

After a pause, Vernon also takes Petey into his arms. This is the same Vernon who routinely refers to Petey as a “bitch.”

That night as I drive home, I see Petey, still at his spot, flying his sign. He is standing on one leg, flamingo style, to relieve the ache, wobbling weakly with his eyes closed.

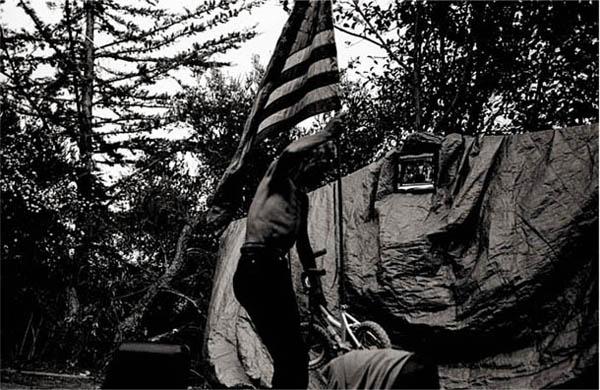

Two weeks later, Petey was unconscious in his hammock:

Hank: He’s laying there, not moving around. I figure he’s dopesick, so first thing is I give him a shot. I tell him, “Pick up your blankets and put them behind the wall in case Caltrans comes.”

But he is stumbling, mentally gone. “That’s it, Petey. You’re going to the hospital.” He collapsed on the damn bus. When I picked him up, I realized how light he was. I undressed him in the emergency room on the gurney to put on his hospital gown. He was comatose. It fucked my mind over how skinny he was!

A guy can only take so much. What am I, a black widow? I can’t even keep myself fixed anymore. I’m mentally fucked up. I’m physically fucked up. I’m just fucked! I don’t even got a blanket. Caltrans came again when I was visiting Petey in the hospital. I’d only had the blanket for two days. Got it at the hospital when I brought Petey in. Caltrans has found the spot where I hide my stuff [pointing to a crevice in the retaining wall]. They come every day now.

Petey won’t survive another battle like this out here and I won’t survive either. I mean, I can’t. And now [grimacing] I’m gonna lose Petey.

Hank visited Petey in the intensive care unit (ICU) every day. Most people on the boulevard expressed their solidarity, but the only ones who actually visited Petey, besides Hank, were the African-American members of the network—Carter, Sonny, and Stretch. In fact, they often moved around the city actively. They visited family members and sometimes explored different neighborhoods or tourist sites for fun and for opportunities to steal. Their proactiveness contrasted with the passivity of the whites, who rarely left the six-square-block perimeter around Edgewater Boulevard that bounded their universe. Once again, these ethnic distinctions, operating at the level of habitus, were expressed as racialized moral attributes. Carter, for example, grumbled that the whites “can’t even take just five fucking minutes to visit Petey.”

I hop on the bus with Hank and Sonny to go visit Petey in the hospital. Hank gives me a transfer ticket that is still valid from his trip earlier this morning and pays the thirty-five-cent senior citizen discount fare for himself. Sonny pretends to look for change from an overflowing gym bag that he has been carrying for the past few days. He pulls out a squeegee, which he hands to me, followed by a North Face down vest. It is 3:30, and the bus is packed with school kids. Sonny fumbles with a Styrofoam take-home container from a restaurant and pops it open, letting a half-eaten piece of garlic bread drop out. Irritated, the bus driver waves him through.

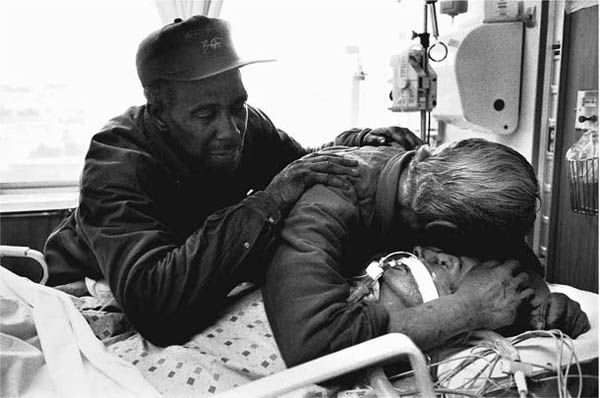

Inside the ICU, Hank rushes to Petey’s side. Petey’s legs dangle like twigs from his protruding hipbones. He weighs only ninety-four pounds. Tubes run through his nose and in and out of his neck and chest. One eye is shut, while the other is a quarter open and rolled back, eerily revealing the white part of the eyeball. His paper-thin lips form an uneven opening, barely wide enough for breathing. A gray-black scab, the color of pencil lead, has formed over his gums, spreading across his lips and tongue. His beard is growing unevenly, just a strip of whiskers on his sunken cheeks: the bones look thick and protruding. A blue and white tube stretches from a machine to the side of his bed down into his throat, suctioning his breath. The room resonates with the whoosh of the pumping air.

Hank kneels down and places his cheek next to Petey’s, pleading for “Bubba, Bubba, my Bubba” to regain consciousness. Sobbing, he gently strokes Petey’s hair to make it flow neatly back over the crown of his skull. His caresses change to a playful tussle, the tips of his fingers intermittently massaging and tangling the hair. “Promise me, Bubba, that you’ll hang in there. Keep your promise to me. I love you.”

Throughout this, Sonny is holding Hank’s shoulders from behind saying, “Look Petey, Hank loves you and he’s holding you; and I love you and Hank; and I’m holding Hank; and Jeff is here too; and he loves you. Everyone’s rooting for you. Lord, please protect our Petey.”

A pulmonary specialist enters with a resident and an intern, and they use Petey, with his pneumonia and spiking fevers, as a teaching case. The specialist removes the tube from Petey’s throat and asks the intern to “reintubate” Petey. They are polite. Before rushing off to the next patient, they conscientiously provide us with a slew of technical medical information on Petey’s condition that we do not understand.

Petey lets out a rasping groan. With a Q-Tip, the nurse gently swabs his lips, tongue, and the inside of his cheeks with Vaseline. She cannot give him water because it will cause the blood clots on his lips, in his mouth, and down his throat to burst.

In comprehensible language, she explains the consequences of Petey’s cirrhotic liver: His bloodstream lacks the crucial proteins that stop bleeding, because the liver produces the body’s clotting factors. Furthermore, the blood and other bodily fluids that can no longer be filtered through Petey’s liver are being pushed through the cells into his stomach and through the lining of his throat. Luckily, Petey has self-cauterized his throat by burping up acids. Otherwise, the nurse explains, his throat would be bursting with blood too. This explains why his lips are oozing blood.

Hank (who presents himself as Petey’s stepfather) asks the nurse why Petey’s stomach is no longer bloated. She explains that yesterday they stuck a needle attached to a catheter in the space between the abdominal wall and the bowel to drain the trapped fluid. She tells us that Petey will need this procedure, called “tapping,” for the rest of his life because of his damaged liver.

Later, the nurse tells us that the guest visiting with Hank yesterday “stole a tray of food from a patient.” It was probably Stretch; every morning he comes to the hospital to check the roster for someone to visit, hoping to steal meds—or anything else of value. Last week he walked off with two telephones.

Hank pulls the covers off Petey’s legs to rub the calluses on his feet and exclaims, his voice rising in a songlike sob, “They’re cold!” The nurse gives Hank a bottle of baby oil, which Hank massages into Petey’s legs up to his thighs.

Hank leans over to pop a pimple on Petey’s ear. Noticing me watching, he says, embarrassed, “But that’s what we do out there, Jeff.”

Politely, the nurse asks us to leave. They want to keep Petey unconscious so that he does not burst the clots in his throat and mouth. She shows us how his heart rate becomes erratic when he is agitated. Petey is safer sedated and undisturbed.

On the drive back to Edgewater Boulevard, Hank becomes anxious about Caltrans. He decides to “dig a hole like a squirrel and line it with cardboard” to hide his belongings.

During the second month of Petey’s hospitalization, Hank’s cerebrospinal infection flared up again. He found himself on the fourth floor of the hospital, in the skilled nursing ward, with Petey downstairs, finally out of the ICU. To everyone’s surprise, Petey had regained some strength and mobility. The two running partners took turns visiting each other, towing their IV drips behind them. Jeff watched awkwardly on one of his visits when a nurse caught Hank adjusting the dials on Petey’s analgesic IV drip. They struggled for control of the mechanism until Hank finally wrenched it out of her hands, knocking over his own IV stand: “I can do whatever I goddamn please to my son!” The nurse ran screaming for a doctor, with Hank chasing after her, shouting, “Go get him! I ain’t scared! I’ve been attacked by the FBI and the CIA! Our government trained me in Vietnam, and let me tell you something, they trained me very well. I can take pain and dish out pain.” Hank stomped back to his room upstairs, yanked out his IV, and left for Edgewater Boulevard, his hospital gown spilling below his leather jacket.

Two weeks later an ambulance brought Hank back to the hospital after he collapsed while panhandling at Petey’s spot. This time, in addition to the IV antibiotics, the doctors included an extra heavy dose of opiate-based painkillers. Once his heroin withdrawal symptoms were fully alleviated, Hank morphed into a friendly, cooperative patient. Clean and neatly shaven, color returned to his face. He hotwired the television set in his suite to bypass the hospital’s service fee, and his room became the ward’s hangout scene for recovering addicts. On several occasions, Hank shared a bag of heroin with visitors in his bathroom.

Jeff visited the hospital on Hank’s fifty-fourth birthday.

Pointing to three pink carnations in a vase on the counter by his bed, Hank announces proudly, “They’re from Petey.” Petey, who is visiting from his room downstairs, blushes shyly. Hank points to another bouquet on the window sill: “They’re from Carter and Tina.”

Petey’s clotting factor is still weak, and he goes to the bathroom to stanch the flow of blood from a shaving cut. He stays for at least a half hour, prompting Hank to quip, “You jackin’ off in there?” Without missing a beat, Petey responds, “I’m tryin’,” his voice a rasping whisper as a result of his seven weeks of intubation in the ICU. Laughing, Hank retorts, “I’ll help you. I used to choke chickens for a living; let me try choking yours.”

Before ending this birthday visit, Jeff stopped at the nurses’ station to inquire into the status of Hank’s SSI disability application. His query was dismissed by the overworked, harried head nurse: “The social workers do that. Not us.”

The brief period of medicalized respite in the lives of Hank and Petey was cut short by the trickle-down effects of neoliberal “reform.” The federal government’s Balanced Budget Act of 1997 had initiated a long-term reduction of $112 billion in the Medicare budget. Federal Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements no longer covered costs (Guterman 2000). In response, private for-profit and nonprofit hospitals began diverting more of their uninsured and Medicaid patients to county hospitals, which were still required by law to treat the indigent. In 1999, the year Petey and Hank were cycling through the emergency room, San Francisco’s public health budget shortfall was projected to be between $26 million and $29 million (San Francisco Chronicle 1999, May 5).

Hospital administrators pressured doctors and nurses to institute “early release plans.” Petey was discharged from the hospital as soon as he was taken off his IV. Hank, who was still on the skilled nursing ward, was furious: “Some doctor told the nurse they needed Petey’s bed. ‘If he can walk, he can leave.’ ” Hank was still attached to his triple-antibiotic drip but knew that his own early release was imminent. The hospital was unable to provide Petey with its usual seven-day hotel voucher. There were no low-budget rooms available in the city because for the past several months a series of fires of suspicious origin had been sweeping through San Francisco’s SRO hotels, allowing their owners to bypass rent control laws and renovate their properties into luxury tourist establishments. Petey, consequently, was sent to a shelter in a neighborhood overrun by drug dealing. A public health van from a pilot outreach program known as the Homeless Death Prevention Project was supposed to shuttle him to the hospital’s outpatient wound clinic every morning. But Petey immediately fell through the cracks.

Ironically, these medical and social service cutbacks occurred at the height of the Bay Area’s economic boom. The mayor of San Francisco was celebrating a $102 million surplus for the city even as the county hospital was implementing draconian cuts (San Francisco Chronicle 1999, May 5). Sixteen county hospital maintenance workers were laid off, and one of the pharmacies was closed (prompting the hospital to hire four security guards to control the crowds of indigent patients who now had to wait in line for up to four hours to receive free prescriptions). A co-payment plan was instituted to force uninsured outpatients to share the cost of their prescriptions. Doctors’ salaries, however, were increased. Coincidentally, Philippe at the time had recently become chair of a department in the medical school that staffed the county hospital.

At this month’s Chairs’ Meeting, the chief administrator presents an Armageddon scenario of the county hospital’s finances. The hospital is having trouble retaining doctors and nurses because of burnout; the shortage of medical staff has caused them to divert 41 percent of emergency medical vehicles to other sites. There is no longer any trash pickup in nonpatient areas. They had an epidemic of antibiotic-resistant streptococcus in the ICU and were forced to shut down cleaning services in the rest of the hospital in order to assign all the limited cleaning personnel to the ICU. One of the ICU rooms has been closed, and they are now treating ICU patients in postoperative care rooms. (I remember the ICU nurse explaining to Jeff that the secondary pneumonia and throat infections that complicated Petey’s liver condition had probably been contracted inside the hospital.) An internal survey revealed that 22 percent of patients sick enough to be admitted to the hospital waited eight hours in the emergency room.

Just before this presentation of what the dean calls the “inhumane conditions at San Francisco General due to federal Medicaid cutbacks,” he announced that the university was raising its mortgage subsidy limit for newly hired clinical and research faculty to $900,000 on the grounds that “it is a hardship to relocate to San Francisco and be forced to buy a $1.5 million three-bedroom home.”

This institutional budget crisis for social services for the poor occurred in the context of one of the most rapid accumulations of regional and personal wealth in U.S. history. It had a predictable impact on Hank and Petey.

Petey has missed all of his clinic and SSI appointments. My stomach turns when I find him panhandling at his old spot by the Taco Bell exit sign in the pouring rain. His brown leather jacket is waterlogged and is taut against his shrunken, bony frame. His hospital crewcut highlights his pale, gaunt features. The scabs on his face have reopened, and he still cannot talk clearly because of the scarring in his throat. This reminds me that medical students have told Philippe that their supervisors instruct them to practice their intubating skills on unconscious indigent patients. Petey’s teeth are chattering, but he does not complain of being wet or cold.

Petey: “I don’t know what the fuck to do, Jeff. They threw me out of the hospital after two months in a coma. They gave me a prescription and told me to move on. They never told me to return for an appointment. And I can feel my liver going. My liver is going, Jeff!”

I offer to give Petey a ride to the county hospital, where I have arranged to meet Hank at the pharmacy, but he refuses to leave his panhandling spot. He is scared of being left dopesick, because he is not sick enough to be admitted into the hospital for an overnight stay.

Frustrated, I drive to the hospital alone, hoping Hank will show up. At the hospital pharmacy, more than one hundred people are waiting in snake coils of lines to get their prescriptions. Hank walks by without noticing me. He is carrying an old briefcase with a broken handle overflowing with his SSI papers. He was released only a week ago but already looks like a wreck. Loaded on both heroin and Cisco, he slurs his words and smells awful. While in the hospital, clean, warm, and well-fed, he had looked rested. He had eaten, bathed regularly, and been adequately medicated for opiate addiction (a combination of methadone, morphine, and Fentanyl). He had also stayed completely free from alcohol, even if he did “chip” an occasional hit of heroin in the bathroom.

After three hours in line, we finally make it to the bullet-proof Plexiglas pharmacy window. Hank is handed a piece of paper outlining his “rights to medication,” but he does not have the fifty-dollar co-payment for his morphine sulfate prescription, and neither do I.

We head to the hospital social worker’s office and wait in front of the desk until she finally has time to talk to us. She tells us that Hank still has an “incomplete dossier” and that his “reconsideration hearing” for missing his last set of SSI appointments is in only two days. He needs to complete yet another set of forms before that meeting, but they must be picked up in person at the downtown SSI office.

I have trouble starting my car as we head back to the boulevard. Hank tells me to pop the hood and walks down the block, looking in the gutter. Moments later, he picks up a hollow pipe and places it on my revving engine like a doctor with a stethoscope to diagnose my ailing car’s problem. He reassures me that it is “only the distributor points or the spark plugs that need to be cleaned—nothing serious.”

When we drive up to the corner, Tina immediately intercepts us to announce that she caught Petey with a Cisco in his jacket pocket. She tried to confiscate it, but he guzzled it in front of her. “And I offered to buy him a beer instead, because that Cisco will kill him, and this here [holding up a sixteen-ounce can of Olde English malt liquor] is more like water.” Hank bursts into tears. Petey has started throwing up again in the mornings. Hank shoplifted Maalox for him at the Walgreens a couple of days ago, but it is not helping. Petey claims that his nausea is caused by eating too much Taco Bell hot sauce, but it is obvious to all of us that his liver is starting to fail again.

Hank confides, his forehead straining at the memory, that Petey defecated in his pants yesterday because the manager of the Taco Bell no longer allows his workers to “buzz Petey in.” Petey rushed to the McDonald’s across the street, but the bathroom was occupied. “This is the second time this week that Petey has had an accident. He just crawls into bed and weeps. I told him last night. ‘I’ll clean you. I’ll wipe your ass for you, but you need to tell me what’s wrong.’ ”

Tina has been giving Petey the two cans of Boost, a fortified high-protein drink, that she picks up each week at the needle exchange, but Petey is not gaining weight.

Petey returns from panhandling accompanied by Philippe, and Hank invites us to spend the night. We walk across the street and pick up carpet padding from the dumpster at the rug store and then climb over the chain-link fence to reach the encampment. Petey is skinny enough to squeeze through a gap between two corner fence posts. Their new camp, nicknamed “the nest,” is ingeniously camouflaged as a heap of rubble. Hank has gathered branches, twigs, and dried pine needles onto a heap of dirt and sand, excavating a circular concave structure. It is just deep enough for us to duck our heads when the police drive by.

In the candlelight and with the reflection of passing car headlights, we try to sort through Hank’s mess of SSI papers, but it is too complicated. I show them some photos of Petey in the hospital, and Hank bursts into tears.

Petey squints closely at each picture, asking for extra copies to send to his father, who was contacted by the hospital social worker when the doctors thought he was going to die.

Hank tells us that when he and Petey are cold at night, they rub their bodies up against each other. On some nights, he reaches out to touch Petey’s body to make sure that it is still warm and that he is alive.

Petey: “Without Hank, I’d be dead.”

Hank: “If Petey died, I’d be dead.”

Unfortunately, by the late 2000s, there had been no improvement in the crisis in funding for social services and medical care for the indigent. Across the country, private hospitals continued to scramble for profits, and public hospitals struggled to stay solvent. Access to basic medical care became even more difficult for the uninsured (New York Times 2007, February 23). Furthermore, there was still no systematic coordination between high-tech medical care and social services. At the local level, law enforcement continued to dominate public spending and political discourse to the detriment of public health. At the national level, for the first time in half a century, military spending reached levels comparable to those of World War II (New York Times 2008, February 4).