I believe that with strong determination and willpower, I could get clean one hundred percent. I think I could do it in twenty-one days. I’m going to try my damnedest, Philippe. Let me say that. —Carter

In 1996, the San Francisco Department of Public Health declared that it would provide “treatment on demand” to drug users. During our dozen years of fieldwork, however, treatment on demand was never available for the homeless (see critique by Shavelson 2001). Addiction is not simply biologically determined; it is a social experience that is not amenable to magic-bullet biomedical solutions. Although many heroin and crack users (no one knows the proportion) eventually manage to cease using drugs permanently, most of them fail treatment most of the time. Treatment advocates argue that relapse is “normal” and that every single day of sobriety should be considered a success. The challenges of treatment are exacerbated by inadequate public funding and by a lack of coordination between detox programs and long-term social support services.

All of the homeless on Edgewater Boulevard asserted on many different occasions that they wanted “to go clean.” Almost all entered treatment programs more than once during the years we spent with them. They were often motivated to seek help by sudden life crises. This was the case, for example, with Tina’s decision to seek help when she suddenly found herself alone in the abandoned factory camp after Carter’s arrest (described at the end of the previous chapter). She benefited from the exceptional support of a pilot public health outreach team. Even with the team’s advocacy it still took her six weeks to get access to an inpatient detox program.

When Tina was finally given a date for an intake interview at a treatment center, Jeff offered to pick her up in his car on the morning of her appointment to make sure she did not miss it.

Tina is waiting for me outside the Mount Hope Baptist Church, where she just received ten dollars for picking up her HIV test results from blood that was drawn two weeks ago by public health epidemiologists. She hugs me, declaring loudly that she has already drunk an entire bottle of vodka and is “driving everyone crazy.” It is only 9:00 A.M., but I am relieved to see that she has brought a duffel bag with her.

Hopping into the front seat, Tina announces: “First I’ll get my crack. Then a hit of hop [heroin]. . . . We goin’ to my program and I’m fit to get loaded on the way! This is my last for two years.”

I start driving rapidly toward the treatment center and try to talk her out of her plans. Outraged, she threatens to jump out of the car if I don’t turn around “and let me have my last hit of crack.” Scared to let her out of my sight, I reluctantly agree to drive back to the crack-dealing stretch of Third Street.

At a busy intersection, Tina crumples a handful of one-dollar bills and drops them under her seat. The next thing I know, she has jumped out of the car and is flashing money and cursing in the middle of the street surrounded by four young men. The shouting suddenly stops, and they all turn around to look at me. One of the young men slowly walks over, knocks on my window, saying matter-of-factly, “One more dollar.” Furious at Tina for putting me in this position, I reach under the seat and carefully pull out only one dollar from the clump of crumpled bills she left behind. I hand it to him through the corner of the window, terrified he will see my camera and tape recorder at my feet.

Back in the car, Tina immediately loads her pipe. Ignoring my protests, she asks me to raise my window to maximize the concentration of crack fumes. I insist again that we must leave for the program, and this triggers a rant: “And I’m gonna spend my money on me!” Her first hit of crack escalates her anger, but it dissipates as quickly as it flares. In a quick change of mood, she is chuckling about how she is faster than any of the men at hustling money when she washes windshields at traffic intersections: “I can get five dollars in a half hour because women don’t like to stop and give money to a man.”

Seizing on her mood swing, I interrupt: “Okay. There are tons of cops out; let’s get to the program right now before it closes.” She ignores me. She opens the car window and yells out to a middle-aged woman who is standing on the corner wearing a gold mesh top with a black brassiere underneath. “Hey, Pauline! It’s me. You got an outfit for sale?” Pauline holds up two fingers and Tina shakes her head, frowning, “I only got one dollar, baby, but I’ll give you a little hit of crack. Come on, please! It’s me.”

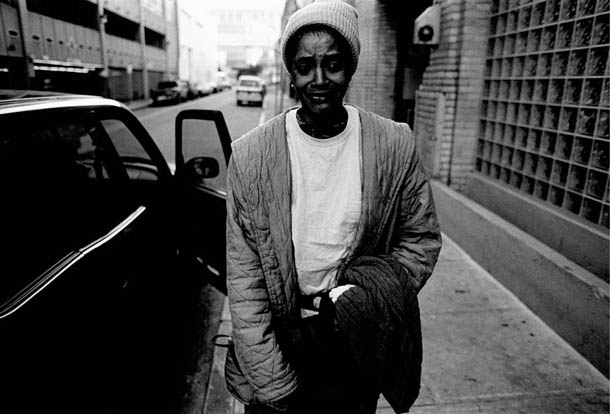

As Pauline climbs into the back seat, Tina opens her hand to show me a few specs of crack in her palm, giggling in a whisper, “This what I’m gonna give her for the rig, Jeff.” Pauline’s face has one scar running along her right cheek and a second scar wrapping around her neck. She immediately grumbles about the size of the specks of crack, but scrapes resin from the stem of Tina’s pipe and manages to eke out a decent hit.

Tina is genuinely happy to see Pauline and proposes enthusiastically, “Come help me look pretty for going into the program. Help me choose my shoes and do my hair.” Without pausing for an answer, she grabs Pauline’s hands affectionately and points to a bevy of dealers on the far corner and asks, “How much money you got?” I protest again that we have to hurry to get to the treatment center before it closes.

Tina: “See, Pauline, Jeff ain’t no trick. The only thing he is worried about is getting me to my program on time. But I want my hair done. [pouting at Jeff] And I go get my crack, my hop, with Pauline. [suddenly happy again] Pauline gonna dress-braid my hair! I wanna be pretty, Jeff. [turning to Pauline] Will they let you do my hair in the program? You wanna go to the program with me?”

Jeff: “Come on, Tina! Enough!”

Pauline: “If you quit talking and go do what you doin’, I have all your hair braided by three o’clock.”

Jeff: “Three o’clock?! No way! It’s eleven o’clock now.”

Tina: “See, Pauline, Jeff want me in treatment—”

Jeff: [interrupting] “By eleven-thirty!”

As we drive to Pauline’s house for her to pick up clothes and hair-braiding supplies, I explain to her that I am a researcher at the medical school. Pauline responds, “My old man has HIV and they want to do a study on me of why I don’t have it.” Tina hands her another pipeful of crack.

While Pauline is in her house, Tina takes out a mini Ziploc bag, the kind used to package crack, and fills it with little chunks of white plaster. I realize she is preparing to take advantage of the moment before going into residential treatment to “burn” someone and avoid retaliation. Pauline comes back carrying a roll of toilet paper, a piece of ivy to plant, a large metal comb, and some clothes. We circle around the neighborhood for another half hour until Pauline finally finds her “old man,” selling heroin in a liquor store parking lot.

At Tina’s camp, Pauline picks her way through the collapsed tarps and piles of soggy clothes and wet furniture and bursts into tears.

Pauline: “No, no. Tina, no-o-o-o! You was staying down here and I got a big ol’ house? If you didn’t have no income, you know I would . . . [angrily] Carter had you out here? Look at this! You outside! Living like a motherfucking dog! [shouting] This ain’t cool, dude! If Carter were any type of man, he woulda’ been trying to get to a motherfucking program for his motherfuckin’ own self. [turning to Jeff] Am I right or wrong? [turning back to Tina] I’ll slap him with my dick when I grow one! [to Jeff again] Excuse my language, but that’s how we talk. . . . I’m not trying to be funny or nothing, ’cause I know you not no trick or nothin’, ’cause you trying to get Tina into a motherfucking program. . . .”

Tina: [softly] “See, Jeff, that’s why I asked Pauline to come with me today. Pauline, tell Jeff about my sister, Sylvia.”

Pauline: [lowering her voice] “I ain’t gonna talk about Sylvia because there be more tears. . . . I called her Chocolate; she called me Cream.”

Tina: “If Pauline had been around, my sister would be alive. Pauline would have killed that bitch before she got my sister. ’Cause her and my sister beat everybody up. They was tough sisters, always together.”

Pauline: [gently] “I had went to the penitentiary so I wasn’t with Sylvia the day she got stabbed by that ho’. God called her.”

Tina: “God put Pauline in her life for my sister.”

Pauline: [hugging Tina] “You my nigga.”

Tina: [turning to Jeff] “Pauline and my sister whoop Third Street niggers. They got battle scars.”

Pauline: [louder] “Mens cuttin’ us up. [touching the scar on her neck] But they couldn’t whoop us. Now I couldn’t whoop no man no more, but back then I weighed two hundred twenty-five when I got out of the pen. And when I was pregnant I weighed two sixty.”

Tina: “How much did my sister Sylvia weigh?”

Pauline: “Sylvia weighed a good . . . hundred eighty, but don’t talk about her no more or else I’ll go to the Fillmore right now and try to find that ho’ who killed her.

“Bitches was jealous of us. I’m tacky now, okay. But I was raised in a middle-class black family, which she . . . [pointing to Tina and shaking her head in disgust at the camp] was too!”

Pauline opens the balloon of heroin she just bought and, as she hands it to Tina, deftly pinches off a small chunk from it with the tip of her fingernail. She then gives Tina instructions on how to “cook it up good,” as if teaching her how to bake a cake.

Pauline: “Stir it up, girl? Good. Now put a little cotton in there. Okay, good; now wipe your arm off. . . . [turning to Jeff] I used to be an LVN [licensed vocational nurse].”

Tina: “She and my sister took me to nursing school with them.”

Pauline: “But Sylvia didn’t want to stay after we had to deal with dead people.”

Tina falls into a deep nod immediately after fixing, her head dangling between her legs and her forehead practically scraping the ground. Pauline, in contrast, is barely affected. She asks me to fetch “kindle” to build a fire to heat the comb for Tina’s hair, and I despair at ever getting Tina to the program.

Pauline pulls a wire mesh out from under a pile of clothes to use as a grill to heat the comb over the flames of her makeshift fire. This prompts Tina momentarily out of her nod: “Don’t do that! There some rats might come up through there. Leave that shit alone—it’s Carter’s.”

Tina starts trying on the clothes that Pauline brought for her—a red, strapless, shoulder-baring cocktail dress; black panty hose; and black patent leather high heels. The clothes reveal how emaciated Tina has become. Her jutting collarbone forms a shadowy concave ring at the base of her neck and her skin has become almost translucent, making her veins stand out. Pauline compliments Tina on her new purse. Tina smiles, “It’s mine. I just stole it at Walgreens yesterday.”

Finally, Tina begins packing her belongings for the program. As she grabs her syringe, I warn her, “You can’t take that rig in there, Tina.”

Tina: “I’m not, Jeff. I’m just settin’ it here so’s that I can do my next hit.”

Jeff: “ What! Your next hit!? No way! We got to go to the program!”

Tina: “Yeah! But I only did forty ccs and I saw Pauline settin’ some aside. And I gave her ten dollars and my crack.”

This provokes a twenty-minute cursing match between Tina and Pauline. The pain of their lives pours out as they argue about their fair shares of the twenty-dollar quarter gram of heroin Pauline bought from her husband.

Tina: [tears streaming] “Don’t do me like that! [in one breath] I’m-a-fuckin’-dopefiend-but-I’m-fit-to-go-to-the-program-and-I-ain’t-got-no-more-goddamn-dope-and-I-just-want-me-one-more-hit-of-dope. And I want my hair done now!”

Pauline: “Good Lord, have mercy. Look at those tears. [pointing to Jeff’s camera] Could you please take a picture of those tears!? Motherfucker crying about motherfuckin’ dope. . . .”

Tina picks up a half-eaten blueberry pie, and Pauline jumps to her feet.

Pauline: “Don’t you throw that pie. ’Cause you goin’ to a motherfucking program and I don’t give a fuck about you getting no attitude. [turning to Jeff] She’s been pulling that shit ever since she was a little girl, picking up things, throwing shit.”

Pauline finally gives in and starts tearing apart her purse, looking for the missing pinch of heroin.

Pauline: “Jesus, please let me find this hit. God, please! I don’t ask you to help me find no drugs, but I need to find this right now. [finding the speck of heroin] Here you go. Take it all. I ain’t never seen you clown behind no narcotics like this. Never! If I’d knew it was gonna be like this I woulda’ got me a piece of crack instead. I don’t have to play no games. [turning to Jeff] My man got dope and my son deal heroin. Tina hogged it. I did not beat [hustle] her! [sobbing] And she makes me feel like a scandalous dog.”

Tina: [crying too] “What did I do to deserve this? I just wanted some more dope. Why you trippin’?”

Pauline: “I’m not trippin’. I got fucking feelings.”

Tina: “You gave me less. I swear on my dead sister you did.”

Pauline: “I swear on my dead baby! I gave you half. I swear on my dead grandson that you got half! [turning to Jeff] Please just take me home.”

Tina: [calm again] “Let’s say we didn’t hear each other. . . .”

Pauline: “I’m through with it. I’m through with it. I still love you. . . .”

Tina: “This dope ain’t comin’ between us. . . .”

Pauline: “No, the dope ain’t comin’ between us, but we can’t do no narcotics together no more. No more. Because I want you to come out of that program clean and I want you to stay clean.”

Tina: “You watch and see. I’m gonna stay clean.”

After we drop off Pauline at her house, Tina manages to fix one last time in the front seat of my car and then breaks off the needle tip and throws it out the car window. With relief, I watch in my side-view mirror as the syringe rolls to a halt in the gutter. Tina falls into a deep nod, and I speed to the intake office before it closes at 4:00. We arrive at 3:15, with forty-five minutes to spare. In her red strapless dress, Tina stumbles on her high heels up the stairs to the second floor office. I follow, carrying two ripped black plastic garbage bags full of clothes, with a pillow and a stuffed teddy bear spilling out.

The counselor, surprised, invites us to sit on folding metal chairs. Tina moves hers closer to mine and bursts into tears. I put my arm around her shoulder, lamely reassuring her, “It’s okay to be scared. . . . Everything will be fine.” She pouts, explaining to the counselor, “My tears are both happy and sad.”

I am relieved to see that the counselor is empathetic and spends a few minutes easing Tina’s nerves. He then calls the detox center to confirm whether Tina’s bed is still available. They inform him that Tina cannot be admitted without a blood test. He hangs up the phone, shakes his head, and sighs. I plead with him to make it work and describe the ordeal of the last six hours trying to get her here. The counselor appears moved and rushes downstairs to the public health clinic.

We wait nervously for ten minutes and Tina cries silently until the counselor returns with the good news that the nurse has agreed to squeeze Tina in at the front of the line. Before medical intake, however, Tina still has to complete a formal “social work readiness interview” in another office down the hall. There is also a long line at that office, but in yet another stroke of luck the security guard, who has overheard our commotion, pushes Tina ahead of everyone. As we walk into the social worker’s office, she is chastising a patient for coughing: “Go over to triage and get yourself a mask. I’m not getting sick because of you.”

Tina cannot find her identification card (she forgot it in her purse upstairs), and the social worker, irritated, calls out, “Next person in line.” Luckily, the counselor has accompanied us and he runs back to his office, returning just in time with the purse. Tina rifles through it, shivering uncontrollably, and in the process tears off the strap of her new Walgreens purse. Finally she holds up her ID triumphantly.

After completing the readiness interview, Tina runs to medical triage, where the nurse accidentally drops the thermometer that she is about to place in Tina’s mouth. Tina protests, “Could you wipe that off first?” and then turns to me and mouths silently, “Lesbian.” By the time Tina finally emerges with all her paperwork, the driver of the van from the detox program is waiting outside impatiently. She refuses to climb on board, begging me through her tears to drive her. She finally gives me a long hug and jumps in, sobbing.

Seven days later, Jeff sent the following email to Philippe:

Just got off the phone with Tina and she’s kicked! She sounds great and even had the where-withal to apologize for what she put me through last Wednesday with Pauline: “I’m sorry you got upset, Jeff. Pauline somethin’ else! She sweet ’cause of my sister. At first she thought you were a sucker ’cause you white, till she found out you really wanted to help me get in a program.”

At Tina’s request, Jeff brought her mother, Persia, to the detox center on the first open visiting day.

Mother and daughter greet by hugging and nuzzling noses. They sit on the couch, arms interlaced. Tina then serves us coffee and jelly beans, and Persia asks Tina what she does all day. Tina answers laconically, “Go to groups.” They are anxious to be nice to each other, but neither quite dares to hope that maybe this time they might avoid yet another hurtful exchange.

In a picture frame designed to look like the back pocket of a pair of blue jeans, Tina has affectionately placed a photograph of two very young girls posing together. She tells us that the girl on the left is the pregnant fiancée of her eldest son, Ricky. Persia comments that “they are going to hell” for not being married—“I won’t let anyone unmarried have sex in my house.”

When Persia goes to the restroom, Tina tells me she faced her big temptation yesterday while being escorted on the morning stroll to a coffee shop in the program’s upscale neighborhood. She found herself face to face with the coffee shop’s tip jar. The escort was serving as a “perfect decoy.” In the old days, “I would have run off with the jar.”

Toward the end of the visit with her mother, Tina suddenly turns sullen. She attributes this to “mood swings.” Persia hesitantly asks, “Why should I give my precious love when you are killing me slowly?” She then pulls out a little bottle of holy water from her purse and places crosses on our foreheads. She instructs Tina to read from “Psalms and Revelations 1, 2, and 3.” She promises to discuss the passages with her over the telephone next week.

As we step out the door, Tina hands me a pair of nurse’s shoes that she found at the intake center and asks me to take them to her Granny. She is scared that her stepfather might try to con me and warns me, “Just leave them outside the door.” She also tells me to alert Ben and Max that two beds were vacated this morning at the detox. Both of them are currently wait-listed for treatment by the Homeless Death Prevention program, with instructions to call this detox program each morning before 9:00 A.M. “to check on space.” Two weeks have passed with no vacancies, and Tina is excited that they could be admitted tomorrow.

On the drive home, Persia tells me: “Round and round we go, to no avail. I’m tired! I can’t get with somebody. I can’t let myself go. It’s just hope and pray, hope and pray. This is the last time. If my family does not get it together, I will run away and not tell anyone where I go. That’s what I did for two whole years after Sylvia died.”

As I park, she invites me into the apartment and offers me a brand-new photographic enlarger that she bought after taking a photography class at City College. She has never used it. “I prefer you have it, instead of the Goodwill.”

Jeff relayed the good news about the empty beds at the detox to Ben and Max. When they called the next morning from the pay phone outside the A&C corner store, however, they were told there were “still no available beds.” Ben snapped back, “Do I need to grow a pussy to get admitted?” and was immediately thrown off the waiting list by the receptionist. Ben was desperate because a judge had mandated him to serve eighteen months in a treatment program in lieu of the same amount of jail time for shoplifting at Nordstrom. He had been unable to locate a program willing to accept him, and he now had only three weeks left before having to serve the jail sentence. Ironically, later that same morning when he went to a community-based clinic to have an abscess lanced, the intake nurse scolded him, “So, now do you want to get clean?”

Ben’s problem was not unusual in San Francisco. Treatment programs are subject to a punitive “audit culture” (Strathern 2000) and must justify their limited funding by their success rates. They purposefully exclude risky patients by institutionalizing artificial obstacles. One common strategy is to require patients to call their prospective treatment center at 9:00 A.M. each morning for three weeks to “prove readiness.” The logic behind “screening” is not explained to the homeless when they seek treatment. As a result, the byzantine bureaucratic rules imposed by funding imperatives become yet another friction point fueling mutual resentments in the idioms of race, gender, and sexuality. We often heard whites claim that programs were partial to “niggers” and heard heterosexuals denounce treatment counselors as “bull dykes and faggots.” No one recognized that the root of the problem was the precarious funding of treatment services in the United States.

Facing imminent incarceration for “failing” to find a treatment slot, Ben went on a shoplifting spree. In the middle of the Discount Grocery Outlet, he pulled out two backpacks that he had stuffed down his pant legs and filled them with butcher knives. His running partner, Nickie, was waiting outside by the automatic entrance doors and triggered them open so that he could sprint out without setting off the electromagnetic merchandise alarms. Three days later, Ben was detoxing “cold turkey” on the floor of a jail cell while awaiting arraignment. He and Nickie had attempted unsuccessfully to repeat their heist at Walgreens later that same day. Nickie escaped just in time. When she told us the story a week later, she referred to Ben affectionately as having had “a fuck-it-all-take-no-prisoners attitude” on the day of his arrest but also expressed relief and pride at his finally being “clean.” Her equivocal emotions encapsulate the lumpen subjectivity fostered by neoliberalism’s punitive version of biopower, in which law enforcement dominates health services. She admires Ben’s outlaw masculinity, and that includes the ability to endure five days of unmedicated withdrawal symptoms in jail—“cold turkey.”

Tina’s counselors at the detox program spent hours on the phone placing her name on waiting lists for long-term residential treatment programs throughout the Bay Area. They could not release her to her mother’s care because of the history of trauma in that relationship; they could not send her to her adopted grandmother because her stepfather, Arthur, had turned that house into a sex-for-crack den. Tina’s eldest son’s apartment in Antioch was obviously not an option since he sold crack. Nevertheless, the program’s bylaws required the counselors to “graduate” Tina within thirty-one days. They were unable to locate any subsidized counseling or follow-up services and had no alternative but to discharge her to a women’s shelter located in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood, a hotbed of drugs, alcohol, and crime.

Coincidentally, ten days earlier, Carter had been released early from jail, and he returned to the abandoned factory camp. He too had not been offered follow-up treatment services. A work referral program for ex-cons, however, had placed him on a construction job, and he was thrilled. Unfortunately, his first weekly paycheck coincided with a three-day downpour of rain that halted construction. Suddenly idle, Carter’s newly earned legal cash burned a hole in his pocket. He went on a three-day speedball binge and was soon back to being a dopefiend full time. Throughout this process, he had been calling Tina at the detox center from the pay phone at the corner store to congratulate her and to express his love.

The morning following Tina’s release from detox, I head to Carter’s camp at the abandoned factory, but it is fenced off. Workers in hardhats and orange reflector vests are gutting the premises.

The young foreman tells me that “the homeless were evicted earlier this morning.” The ten-thousand-square-foot structure is scheduled to become a mini shopping mall and a food court. This reminds me that shortly before Carter’s arrest, Tina had told me eagerly that the owner of the factory had promised Carter a job in the renovation. Sifting through the junk still left at their old spot, I come upon a half-empty bottle of Trazedone, an antidepressant, with Tina’s name on it.

I drive to Edgewater Boulevard and find Tina washing windshields in the parking lot of McDonald’s.

Tina: “I’m sorry, Jeff, but that place they took me to wasn’t nothin’ but a nasty-ass shelter. When I walked in, they were serving some sloppy food. And I wasn’t going out like that. So I said I could do it my own self. I could take care of myself. Thank God.”

Jeff: “How come you started fixing again?”

Tina: [loudly] “ . . . ’Cause I wanted to, Jeff. I’m a dopefiend. I wanted to make the program work, but I ain’t fit to make like I’m ready . . . and get off this shit. . . . I still like this shit . . . because I’m a failure. I just felt confused, disorientated, overwhelmed.”

Jeff: “But you were a success at the detox. Everyone loved you there.”

Tina: “I’m a loveable person, but I’m a failure. I wanna be clean and sober and get off my ass and do what I need to do for me. But I don’t know why everything changes when I’m on dope. I never complete a damn thing.

“I don’t have no place to go right now, and I’m not fixin’ to go and whine to my mother. I know that I’m gonna want some hop . . . some crack. I can’t do that to her. So I just gotta stay out here and tough it out and get my ass together and just go on.”

Tina took full responsibility for her relapse, despite her counselors’ inability to locate post-detox housing and services. Twelve-step Narcotics Anonymous self-help meetings were the only free and accessible form of post-detox treatment in the United States in the 1990s and 2000s, and they rely on individual willpower and spiritual solidarity. Predictably, most long-term indigent heroin injectors and crack smokers relapse on multiple occasions before finally ceasing to engage in personally destructive patterns of drug use. Without substantial institutional resources, it is difficult for long-term chronic users to figure out how to pass the time of day. They have to construct a new personal sense of meaning and dignity. Instead, they often fall back on their more familiar and persuasive righteous dopefiend ways of being in the world, and they seek out old drug-using friends and acquaintances.

Six months after having been briefly “clean and employed,” for example, Carter was back in jail for a “dirty urine” parole violation and Tina was reaching a new low. She had built a lean-to next to a dumpster in the empty lot by the Discount Grocery Outlet and, for protection, camouflaged it as a mound of garbage. She mourned her relapse, convinced of her own worthlessness, and this deepened her commitment to heroin and crack.

Tina: Look at me! I wake up dopesick every morning. It’s my own damn fault. Carter, he blames hisself and says it’s his fault. But it was my choice. I’m a stupid-ass fool.

You don’t love me no more, Jeff. You don’t come check on me. I know I hurt your feelings when I left the program—and broke your heart. [wiping tears from her eyes with a McDonald’s napkin] I hurt my own feelings and I broke my heart, too. But I tried. That’s all I can say, Jeff.

[voice cracking] I think about it every day that I have to keep hustling to live. Gotta get my high. Last month I got busted pushing a cart. I’m frightened now. I am praying to God they never catch me.

[whispering] I’m eatin’ out of the garbage now, and I think I got food poisoning. I be so tired now. . . . I can’t even eat. My bones achy. Maybe I got the flu. I been washing my clothes by hand and puttin’ them on half-dry. [lighting her crack pipe]

Jeff: Why don’t you just rest tonight instead of hustling for more crack?

Tina: No! No! No! [laughing while inhaling crack] I’m fit to smoke crack, Jeff. But the crack takes my dope away and makes my bones start hurtin’. [grabbing her syringe like a dagger and pretending to stab her arm] Take a picture, Jeff! I’m a dopefiend. I’m not gonna stop livin’ till I die!

Once again finding herself alone on the street with no running partner, Tina drew on her charismatic performance of femininity and used her access to African-American street dealers to broker five- and ten-dollar crack deals for the white men. Normally excluded from performing masculinity in their interactions with women, the white men, under Tina’s tutelage and with Carter locked up, deployed a version of chivalry that protected Tina from violence and benefited her in the balance of the moral economy.

Tina: I never do a whole sack of dope alone. I just sit in the car, and my mens come to me. They loves the hell outta me! All my mens stop by to make sure I’m okay.

When they on crack they come over here wanting a pipe. [imitating Felix’s voice] “You know I love you, Tina. . . .” Frank has three pipes now: a big one, a medium one, and a small one. [notching the sizes along the side of the stem of her pipe] I bought him his first pipe, and now he smokes more crack than me.

And Petey comes by, too, for crack . . . but on the sneaks from Hank. And I tell Petey, “Get your ass on this bus with me.” And we go to Third Street. And we smoke some crack together. I buy him beer ’cause I don’t want him drinking that Cisco because of what he been through with his hep C. And he hasn’t gave up on life. That means a lot.

Hank comes by sometimes too, on the sneaks from Petey, so we can fix some dope together. But I don’t want to feel bad for Petey so I sneaks with him again later for dope. [laughing] Carter and I used to do that to each other, too.

Crossing the lines of intimate apartheid in her relations with men, Tina frequently encountered their routine expressions of racism. On one occasion, we walked up to Frank’s camper to find Tina arguing furiously with him. He attempted to defuse the tension by apologizing to her for being “a white racist grouch.” This made her even angrier: she was hurt and embarrassed that Frank had self-identified as a racist in front of us, even if he was apologizing for it. Later, in private, Tina felt compelled to save face by reassuring us that she never subordinated herself to her white male friends: “I don’t kiss they ass at all. When I get mad, I cuss they ass out.” At other times, Tina made statements that reflected the symbolic violence of internalized racism: “The white people is real nice and concerned about me and what I’m going through out here now. They the nicest ones, white people is.” Moments later, she would criticize whites for their habitus-level deficiencies. For example, when a white couple, who were methamphetamine injectors and running partners, established themselves on Edgewater Boulevard for a few months, she complained:

That new bitch a copycatter—tryin’ to wash windows at my gas station. I beat her ass. Nasty white bitch. . . . So filthy! Her and her husband, I even been keeping them from beating each other. But then he gonna watch me beat his woman’s ass, and he ain’t gonna say shit.

Both of them is nasty. [inhaling crack] They even got dirt on them. Yup! Nasty-ass bitch!

Since the 1970s, the U.S. medical establishment has promoted methadone maintenance as the cure for heroin addiction (National Consensus Development Panel 1998). This has caused considerable political and popular controversy over methadone as a treatment modality. It has been at the center of what Foucauldians call an “intradiscursive conflict.” Biomedical science declares methadone to be a medicine, but contrary discourses of law enforcement, health fitness, and moral and religious abstinence consider methadone to be a dangerous and immoral drug. The “birth of the methadone clinic” in the late twentieth century offers an interesting case study of the emergence of an expensive, conflictive, and humiliating apparatus of governmentality for regulating heroin addicts (Bourgois 2000).

Despite strong support for methadone maintenance by the federal government’s National Institutes of Health, the treatment remained illegal in many Bible-Belt states; federal law required that methadone be distributed solely through specialized clinics and that it be dispensed daily through “directly observed therapy” to prevent its diversion for resale on the street. Furthermore, doses, cost, and accessibility varied across the country (D’Aunno and Pollack 2002), depending on the local influence of doctors, epidemiological researchers, evangelical ministers, for-profit treatment clinics, law and order advocates, and public health budgets. In San Francisco, for example, from the 1990s through the 2000s it was difficult for the homeless to access methadone maintenance because it was administered primarily though private for-profit clinics that charged approximately three hundred fifty dollars a month (Rosenbaum et al. 1996). The county hospital reserved its limited number of subsidized maintenance slots for indigent addicts with one or more potentially fatal medical diagnoses such as active tuberculosis, full-blown AIDS, metastatic cancer, or emphysema. Inexpensive methadone was more readily available through twenty-one-day detox programs, but they had negligible success rates. In contrast, in New York City during these same decades, long-term, high-dose methadone maintenance was easily available to everyone at low cost through large public health clinics.

Methadone and heroin stimulate the same neurotransmitters in the brain. The first time an individual consumes methadone, he or she often feels pleasure and falls into a deep nod. Within a few days, however, patients develop what doctors politely call “a tolerance” for the drug (and what users describe as a physical craving more powerful than that caused by daily heroin injection): the neurotransmitters that simulate a heroin high become saturated, but do not generate pleasurable sensations. Following the logic of biopower, methadone is a technology that is designed to block the euphoria produced by opiates at the molecular level in the brain’s synapses. Critics denounce methadone for being more pharmacologically addictive than heroin: its withdrawal symptoms are notably more severe and prolonged than those caused by heroin. Debates over methadone in the 2000s resonate with those of the 1880s, when the medical establishment hailed both heroin and cocaine as cures for morphine addiction (Bourgois 2000). Nevertheless, for hundreds of thousands of former heroin addicts methadone has been a life-saving substance that dramatically reduces their suffering (Drug Policy Alliance 2007).

In 2002, the United States finally approved buprenorphine as a substitute treatment for heroin addiction, prompting new magic-bullet promises and new counter-polemics among treatment specialists. Whatever the merits of the debate, buprenorphine, in its first years of deployment in the United States, represented one more detox and treatment alternative that thousands of injectors used to stabilize their lives (see Lovell 2006). None of the Edgewater homeless tried buprenorphine treatment, but we met several younger injectors on the periphery of our scene who spoke positively about buprenorphine and who marveled at how much less painful it was to detox from it compared to heroin or methadone.

Most of the Edgewater homeless believed, at least to some degree, that methadone could potentially change their lives. When they obtained legal jobs, for example, and wanted to avoid the necessity of injecting heroin on their breaks, several of them sought admission to private methadone clinics, despite their fears of the drug’s addictive properties and their resentment of the directly observed therapy rules that clinics imposed on their patients. Consistent with the broader ethnic pattern of unequal access to services, none of the African-Americans in our social network entered methadone treatment during our years of fieldwork, whereas almost all the whites and Latinos received methadone on multiple occasions—usually through the relatively cheap, for-profit, twenty-one-day detox venues. None of the Edgewater homeless lasted longer than two weeks in those short-term detox programs because the rapid tapering of the dose caused severe withdrawal symptoms. Although their relapses were pharmacologically predictable and represent an obvious institutional deficiency in the treatment modality, these failures became yet another forum for symbolic violence that encouraged vulnerable individuals to blame themselves for their lack of willpower.

Only one peripheral member of the Edgewater scene was consistently registered in a long-term methadone maintenance program during our time on the boulevard. Chester was legally blind and qualified for Supplemental Security Income. He still lived with his parents in the neighborhood up the hill, and his mother made sure that his treatment bill was paid on time every month through his disability check. Chester drank large quantities of Cisco Berry to boost the latent euphorigenic effects of his methadone. By midday, after his third or fourth bottle, he would burst into tears, calling out for his deceased Native American girlfriend, Carmen. They had met at the methadone clinic and had become inseparable lovers. Carmen was killed during our second year of fieldwork when she ran into rush hour freeway traffic during an argument with Chester. We were never able to interview her because, like Chester, she became incoherently monosyllabic when she combined alcohol with methadone. Years later, Chester would obsessively reenact the horror of her death during the evening rush hour, shouting across the freeway at the top of his lungs, “Carmen! Carmen! Stop!”

Halfway through our fieldwork, Chester’s abdomen suddenly swelled to triple its normal size from cirrhosis of the liver. Six months later he was dead. The Edgewater homeless were convinced that methadone had killed him.

On one occasion, we gave Max, Frank, and Chester a ride to the for-profit methadone clinic where all three were enrolled at the time. Max was beginning the final week of his twenty-one-day detox arrangement. It had been prepaid by a social worker after Max spent three and a half weeks in the county hospital for a skin graft over a large abscess. Frank was self-paying for his twenty-one-day detox in order to finish a large sign-painting job without interruption. Chester was fetching his standard morning maintenance dose. Our conversation in front of the clinic highlights the dissonance between how methadone treatment is experienced by injectors on the street and how it is understood by scientists and clinicians.

Philippe: Explain how methadone works for you, Max.

Max: It sort of stops you from craving the heroin. But now I’m craving the methadone, ’cause I got so used to drinking it every day in the hospital that by the time I got out, I was hooked on it. That’s why they sent me to detox.

Methadone has kept me off the heroin. . . .

Philippe: What are you talking about? You just fixed some heroin twenty minutes ago before we left for the clinic.

Max: Well, yeah. Today I broke down because I was sick. The last three days have been real hard because the dose they’ve been giving me is cut way down now. I mean, I was so sick I could hardly walk this morning. It’s sort of the same as when you don’t have heroin. You start throwing up. It comes out everywhere. Your eyes water; your nose runs. You can’t sleep.

There is nothing they can do about the dose at the clinic unless I had the money to pay twelve dollars a day. But I don’t like the whole idea of methadone. [shouts and curses coming from the clinic door behind us] But methadone works if you let it work for you. You just have to be a little bit stronger than I am.

Philippe: How many times have you been on methadone detox?

Max: Oh, gee whiz. I don’t know, maybe twenty times over the past five years.

[turning toward the commotion at the clinic door] I’m gonna go see what Frank is upset about. Ask Chester about methadone.

Chester: Yeah, I’ve been staying clean. I’m on eighty milligrams. The stuff works. On methadone you’re just like normal. You wake up, you’re not sick at all. I mean, hey, you feel normal. I can get up, smile, brush my teeth and eat, go to work . . . if I worked. I can do things I’m supposed to do: I can shave, change clothes, wash clothes.

You know who invented methadone? I heard it used to be called “Adolphine,” after Adolph Hitler.

Philippe: Not quite, man. It was invented during World War II by IG Farben, the same company that made Zyklon B, the poison gas the Nazis used to kill the Jews.

Frank: [running toward us] We gotta get out of here [pointing to an African-American security guard running toward us]. King Kong over there has a hair up his ass.

Philippe: [scrambling into the car] What happened, Frank?

Frank: They breathalyzed me. I had too much alcohol on my breath. . . . One fucking point over the limit, so they didn’t serve me. I lost twelve dollars! They used to fucking give the money back, but now they say it’s in the computer. Bullshit, man! That’s another scam of theirs.

Chester: [furious] That happened to me, too, for a whole week—just for drinking.

Max: [whispering in awe] At eighty milligrams! You don’t know how wrong that is. That stuff is strong, man. It’s stronger than heroin.

Frank: [shouting] They got complete control of your fucking life.

That fucking bitch nurse! That’s why I’d never get on maintenance again. It’s like being in prison. I can’t stand that. They got you scared all the time. They threaten you: “Do this” and “Do that.” And they fuck with you all the time. You know, fuckin’ following the rules. And then when they get a little hair up their ass about something, they gonna cut you down. And that shit is life and death, man.

Chester: Yeah . . . goin’ into convulsions and seizures that could kill a person!

Frank: It does! It has. They’re just legalized dope dealers. They could give a fuck less about people.

Mandating daily attendance at methadone clinics for directly observed therapy, a requirement imposed by law enforcement advocates, ironically promotes poly-drug use among methadone maintenance patients. For a few hours each morning, the corners surrounding clinics become open-air markets for the drugs that boost methadone’s latent, euphoric effects—primarily crack and benzodiazepines such as Valium.

In 2001, California implemented a voter-approved ballot initiative mandating the option of treatment instead of incarceration for nonviolent, drug-using criminals. Carter was already in jail at the time, but he was granted early release on the condition that he attend a residential treatment program and remain “clean and sober” for ten months. As a military veteran he was eligible for free job training in a program serving the dot-com industry.

Carter’s “computer career” never materialized. He almost obtained a job as a garbage collector through “connections” his niece provided, but he was rejected “ ‘cause I got a bunch of fucking felonies.” Eventually, the Veterans Administration program managed to clear his driving record, and he obtained a license to operate heavy machinery. Soon he was bulldozing fruit and nut orchards south of San Francisco for a developer who was building a gated bedroom community in Silicon Valley’s exurbs.

A month into his new job, Carter arranged to meet Jeff in the Mission District.

Carter is late and I cannot stop myself from worrying. I am waiting on the same corner where I watched him buy heroin for the first time. It is a Latino scene, and after making the buy, he had walked right past me without making eye contact. Back on Edgewater, we had shared a pastry, and he had explained that he had not wanted to risk letting the dealers see him “talking to a white boy.” Most undercover officers are young white men and if, by coincidence, the police had arrested someone later that day, or even later that week, he could have been banned or beaten up simply for having been seen talking to an unidentified thirty-year-old white male at the copping corner within the last few days.

Despite the ongoing War on Drugs over the past six years, this scene remains unchanged today. Dealers are out in full force.

Carter finally arrives, and he looks great. He is at least thirty-five pounds heavier than when I last saw him in court—“all neck,” as Max describes him. We drive to a café in the neighborhood where he grew up and find ourselves surrounded by the new boho residents who have gentrified it. He holds up his key chain, a series of color-coded Narcotics Anonymous milestones celebrating his sobriety—thirty days, three months, six months—and talks earnestly.

Carter: “This is a major, major stepping stone for me in my life, Jeff. At forty-two, being able to do this. Ain’t nobody human out here could of did that. On giving me another chance. I stay ever mindful for that.

“I get tried a whole lot of times. Just last week, my car got hit; I got laid off from my first job in delivery; there was a death in my family. But I ain’t using none of that as no excuse.

“Deep down in my heart and mind and soul I know that I shouldn’t be here. I should have been dead or in the penitentiary for a long time, bro’. I done took a whole lot of people’s stuff.

“I always tried to keep that protective macho image up. In treatment, people cried and hug in groups. Men supporting other men. . . . I never bonded with no men before. True love support. It made me take a hard look at my life. After a few weeks they made me a mentor and that was kinda cool. It wasn’t like that other Choices Program I was in, where they do violence therapy in like, groups. There they do a lot of screamin’ and yell in’. A lot of name callin’, and they try to break you down. They have a sign that says WARM AND FLUFFY. It’s how they want to make you.

“And this year I was bringing in the New Year’s drinking apple cider in a clean and safe environment. Last New Year’s I was drunk, loaded, laying up in the hospital. I had got hit by a car, and my head was bust open.

“And the guys out on Edgewater, when they see me, they talking, ‘Hey, man, I got this bag. You want some of it?’

“I just tell ’em, ‘I fittin’ to go to the store and go get me some juice.’ Right! ‘I been thinking about this Sunny Delite.’ Right! ‘It’s hot and I got a taste for orange juice.’

“Oh Jeff, why don’t you and Philippe come to my graduation from the program on Saturday? My sister’s comin’. My new girl, Clarice. My daughter, my niece, my grandson. Bill, my sister’s husband, is coming. Smokey’s wife is coming, but Smokey can’t be there; he’s in jail again.”

Jeff: “Your grandson?!”

Carter: “Yeah. I’m a grandfather by both my daughter and my son. [taking baby pictures out of his wallet] And this past Christmas they gave me a pass from the program to go visit. I went to my daughter’s house. And we put the little toys together . . . and the puzzles. And we played and wrestled on the bed. . . . Then, you know, we ate and stuff. That’s one Christmas I never will forget.

“The only thing we didn’t do was take no pictures, which was what I wanted to do, but at the time I didn’t have no camera. But I got plenty of time for that.

“You know, Jeff, I drive by a lot of construction sites and see so much wood and opportunities . . . piles of money just sitting right there. [laughing] Contractors, here I come! It’s like a natural reaction—like homing instinct—peoples, places, and things.

“But I just look and laugh. ‘Oh Lord, please dismiss that thought. I’m just looking, Lord. I’m just looking.’ ”

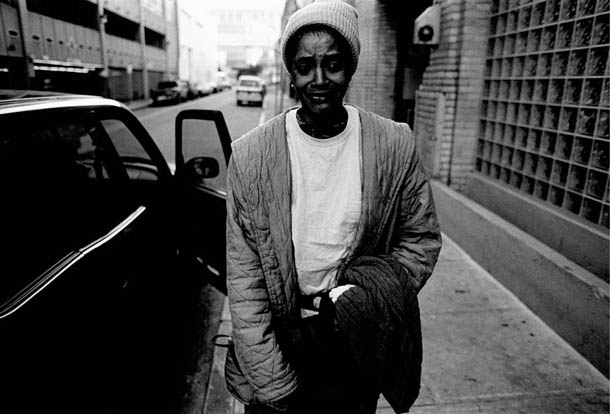

Most of the forty-two graduates at Carter’s drug rehab graduation ceremony were African-American, and most had been mandated to complete the program by the court. The staff members at the treatment program were all African-Americans, funded by the Alternative Programs Division of the sheriff’s department. Evoking the slavery experience, their logo depicted chains “bursting asunder.” Wearing suits and ties, many of the graduates burst into tears at the podium in front of the microphone when they were handed their diplomas. Several of them thanked the district attorney for arresting them. Carter punched the air to the audience’s cheering and announced, “I wasn’t arrested; I was saved.” At the end of his speech, he raised his arms in the air like a boxing champion and shouted, “I did it!”

Following the rules of his Narcotics Anonymous program, Carter avoided seeing Tina, and she responded to news of his graduation from the program like a jilted lover:

Don’t talk to me about Carter. He just likes to stand on the street corner talking in his cell phone to make people look bad.

I seen him last night. I said, “Help me out,” and he gave me a dollar. I gave it back to him: “I don’t want no dollar!”

Two months later, Carter’s bulldozing job ended, and Philippe ran into him on Edgewater Boulevard. With a can of malt liquor in his hand, Carter was celebrating his forty-third birthday with a sex worker who was sitting in the beat-up Toyota belonging to his girlfriend, Clarice. He cut short Philippe’s expression of concern with the quip, “What’s the matter! Wanna turn? I’m just freakin’ with this chick. . . . You can go next; she gives great head.” He then tried to reassure Philippe that he had already found a new position in Silicon Valley, “movin’ office equipment. I like meeting all the secretaries. They talk to me about stock options. In a year, I’ll have enough money to buy a house in Vallejo.” He then kicked the broken headlight on the Toyota and laughed about using the insurance company’s reimbursement money from his accident earlier in the day to make a down payment on an SUV.

Two weeks later Carter died under the freeway in the hole. It was payday, and he had stopped by Edgewater Boulevard on his way home from work. His overdose generated the familiar spate of rumors and recriminations.

Tina: Sonny came by just as I was fixing. He put out his outfit and said, “Sis, could I get a little?”

I gave him some dope. And then he was crying and actin’ all spooky and scary and shit and starts hollerin’, “Tina, Tina!” He was on his knees. “Tina, let me talk to you. It’s Carter. He’s dead!”

I’m like, “What? When? How?”

“The paramedic said he swallowed his vomit.”

I’m like, “Oh, yeah, Sonny. I thought you wasn’t shootin’ dope with Carter? I knew you was. You don’t have to lie to me. When did it happen?”

“About an hour ago.”

At the time I was shockin’. . . . But that motherfucker Sonny was just waitin’ to spend up some of Carter’s money. They robbed him. I found all that out later, ’cause later, every time Sonny came around here, I could see that he be tweakin’. Carter’s pockets was full of money and Sonny probably pulled his coat, watch, and rings too. All I know is, Sonny let him die! Sonny didn’t save his friend’s life.

And if Carter was gonna die, at least he could have died in the hospital, or in the ambulance—not on that damn ground. [pointing to Hank] Hank’s around crying too. He’s crying, wantin’ to kill everybody so I gave him some crack. Talk to him, Jeff. He feels bad too.

Jeff: What exactly happened?

Hank: Well, maybe Sonny and Carlos [a peripheral Latino in the scene] didn’t really know that Carter was gonna die. But they robbed him. They took his money and his jewelry. It was over nine hundred bucks. ’Cause I’d seen Carter earlier that day and he’d had a eleven-hundred-dollar check.

The two guys, Sonny and Carlos, kept hanging around. They wouldn’t leave Carter’s side ’cause they knew he had the money on him.

When the coroner picked him up, he didn’t have no money in his pocket. He had about seven cents, something like that. They couldn’t even find the keys to the car. Sonny and Carlos had their hands in Carter’s pockets. Carter was on his back.

And Jeff, I’m lookin’ for Carter’s brother—Lionel. I got a good idea of what I wanna do to them. . . .

Frank: [walking up with Spider-Bite Lou] I’d kill that motherfucker Carlos myself, if I knew I could get away with it.

Hank: They should have sat Carter upright. They should never have left him laying down like that.

Frank: [softly] Yup. He’s dead all right. [kicking the ground] I’ve had so many friends die in the last few years.

Spider-Bite Lou: [ruefully scratching the scab on the back of his neck] When the devil comes a callin’, he comes screamin’.

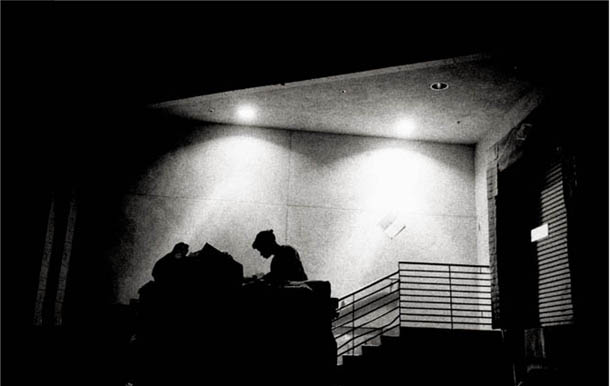

Tina built a shrine to Carter in her lean-to by the Discount Grocery Outlet dumpster. The centerpiece was a plastic wedding cake decoration of a white bride and groom holding hands, bordered by a rose in plastic sheathing and a photo Jeff had taken of her with Carter at the beach. At the base of the shrine she taped three condolence cards addressed to Carter’s sisters. She signed them, “Tina James,” thereby formally taking Carter’s surname. A homeless woman who lived down the boulevard and who had “buried three husbands to overdoses” sympathetically prepared French nails for Tina to make her “look like a lady for the funeral.” As the woman painted Tina’s nails, she gently chided her for not putting aloe on her tracks to hide them. Going in and out of a nod, Tina reported matter-of-factly that the doctors had given her a hysterectomy two weeks earlier. This explains why she had been bleeding, cramping, and urinating so much over the past year:

Thank God it wasn’t cancer. I’m blessed, but I got stitches inside me; and they gave me four pints of blood, two when I got there and two in surgery. They gave me thirty ccs methadone and morphine, and I was well. [smiling] They gave me a voucher for a cab to go to that same nasty-ass shelter the detox sent me to. I put the cab on another destination and went back to my camp next to Frank. The cabbie gave me three dollars from the voucher to get rid of me.

Tina’s medical record confirms that she lost a great deal of blood and notes that she is homeless. Despite these complications, she was released from the hospital early, after only three days.

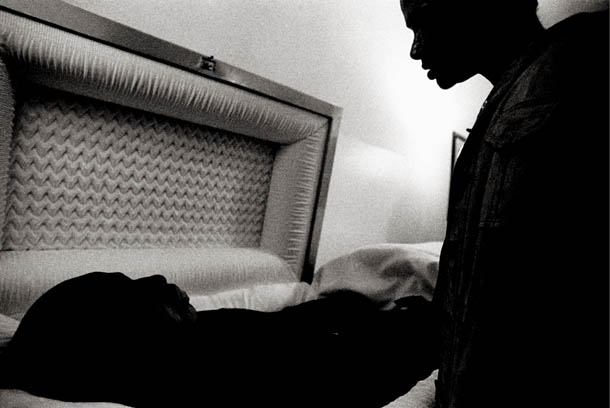

Jeff accompanied Tina to Carter’s viewing at the funeral parlor.

Tina introduces herself as “Carter’s fiancée,” and we are greeted warmly by Carter’s thirty-two-year-old daughter and his thirty-year-old son. The daughter is petite and has Carter’s same endearing smile. In contrast, Carter Jr. is well over six feet tall and weighs at least two hundred fifty pounds. Both children are very calm, soft-spoken, and friendly. Although they have different mothers, and hardly knew their father, they are clearly very close to each other.

Carter Jr. looks carefully at a recent portrait of Carter that I give him and notes that his beard grows exactly like his father’s, reminding me that he is an abandoned son, only now in direct contact with his biological father.

In the parking lot, Lionel, Carter’s oldest brother, walks up to Tina and hugs her. They have not talked since she snitched on Smokey. One of Carter’s grand-nieces (Smokey’s sister) calls Tina “auntie” and reassures her that she will “always have a home with me and my mother.”

Tina did not attend the funeral the next day, nor did anyone from Edgewater Boulevard except for Vernon, who arrived with his wife, the nurse. The preacher made no direct mention of how Carter died or of how he lived his life, but he did blast the outlaw lives of many of the young men and women in the audience in a right-wing evangelical political idiom.

The church is packed with close to one hundred people. Carter’s head is propped up in the casket against a folded American flag. Looking around, I notice that I am the only white person in the room. Beverly, Carter’s oldest sister, stands next to me and graciously introduces me to everybody, explaining that I am “writing a book about Carter’s life.” Several cousins request photographs to send to “family back in Louisiana.”

About twenty members of Carter’s immediate family file in and sit together in the front two rows. I recognize Smokey, who has recently been released from prison. All of Carter’s grandnephews who sell crack for Smokey in the alley by the A&C corner store are also present in the seats of honor.

Carter’s son reads the obituary, highlighting military experience and connections to neighborhood and family. He lists all of Carter’s legal jobs, from “restaurant and food services” to “construction” to his very last position as a “commercial Class A truck driver.”

The preacher begins with a patriotic reference to Carter’s birthday, the Fourth of July, being the anniversary of the “birth of the nation.” The preacher proceeds into a hellfire and brimstone sermon, condemning crack dealing and drug use. First, however, he establishes his credibility as an O.G. who ran the streets with Carter’s oldest brother, Lionel, and was hospitalized twice for overdosing on heroin.

He proceeds to blast hip-hop clothing styles, claiming that homosexuals in prisons wear their pants low and baggy as an invitation to “come and get it. But I know we don’t got no saggers here today.” This prompts a murmured assent from most of the mourners. Smokey and his dealing crew—all of whom “sag”—sit attentive but expressionless in the front rows.

The pastor denounces crack dealers by impersonating a “toss up” [a woman who exchanges sex for crack]: “Mr. Dopester, here is my body; come and get it. And take my twelve-year-old daughter into the back room and do what you want with her, too.”

Moments later, Smokey escorts his mother, Glenda, to the podium. He holds her shoulders throughout her tearful homily, embracing her affectionately when she finishes.

As we are leaving, the funeral director announces that the burial will not take place for another week because “the U.S. Army, by request of the family, is holding a military burial. There will be a twenty-one-gun salute.” The audience cheers.

I drive 106 miles along the Blue Star Memorial Highway to the San Joaquin Valley National Cemetery, a designated national military shrine. At the entrance to the cemetery, five elderly white gentlemen wearing pointed hats and blue shirts sit in the shade of a gazebo shelter. They are the honor guard—all Veterans of Foreign Wars. A van pulls up with Carter’s core family members: his sister Beverly, his brother Lionel, and their spouses; his new girlfriend, Clarice; his niece Glenda; his daughter, Charlotte; and his three grandchildren. Only his son, Carter Jr., is missing.

The funeral director drapes an American flag over the silver coffin and signals for Beverly’s husband, Lionel, and me to lift the coffin onto a gurney. The veterans take turns reading a prepared statement from a three-ring notebook, while the family weeps.

In unison, the honor guard fires off three shots each, producing three echoless “pops.” Charlotte chokes back tears as the veterans slowly fold the flag with soldierly formality. When they are done, they salute one another. The highest-ranking veteran gives the flag to Charlotte, leaning down to meet her eyes and express his remorse. The soldiers follow behind him in line to give their condolences to the family members individually. One of the shooters presents Charlotte with the spent bullet cartridges as “a symbol of patriotism.”

From the cemetery’s vista platform, we watch them bury the casket. Charlotte is now weeping quietly, with two children draping their arms around her. The hearse becomes a tiny speck among other tiny specks, a quarter of a mile away. When it finally drives off, we take this to be our cue to leave.

Carter’s family was presented with a Presidential Memorial Certificate: “The United States of America honors the memory of Carter James. This certificate is awarded by a grateful nation in recognition of devoted and selfless consecration to the service of our country in the Armed Forces of the United States.”