3

COLLEGE YEARS (1875-82)

It has cost me years of thought to arrive at certain results, by many believed to be unattainable, for which there are now numerous claimants, and the number of these is rapidly increasing, like that of the colonels in the South after the war.

NIKOLA TESLA1

Eighty miles south of Vienna, in the capital of the province of Styria, was the Polytechnic School in Graz. Milutin had chosen the school because it was one of the most advanced of the region. The physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach had taught there a few years earlier, as had the psychophysiologist Gustav Theodor Fechner. Planning on becoming a professor, Tesla undertook courses in arithmetic and geometry from Professor Rogner, a lecturer known for his histrionics; theoretical and experimental physics with the punctilious German professor Poeschl; and integral calculus with Professor Allé. Allé “was the most brilliant lecturer to whom I ever listened. He took a special interest in my progress and would frequently remain for an hour or two in the lecture room, giving me problems to solve, in which I delighted.”2 Other courses taken included analytical chemistry, mineralogy, machinery construction, botany, wave theory, optics, French, and English.3 To save money, he roomed with Kosta Kulishich, whom he had met at the Student Society of Serbia. Kulishich later became a professor of philosophy in Belgrade.4

Tesla plunged into his work with great intensity. Studying upward of twenty hours a day, he changed his major to engineering and extended his curriculum to study other languages—he could speak about nine of them—and the works of such writers as Descartes, Goethe, Spencer, and Shakespeare, many of which he knew entirely by heart. “I had a veritable mania for finishing whatever I began,” he recalled, reflecting on his next self-appointed assignment. The collected works of Voltaire comprised “one hundred large volumes in small print which that monster had written while drinking seventy-two cups of black coffee per diem.”5 This task cured him of the compulsion but did not serve to quell the pattern of relentless self-denial and self-determination. Because he was praised by his teachers, the other students became jealous, but at first Tesla remained unperturbed.

Returning home the following summer, having passed his freshman year with all A + ’s,6 the young scholar expected to be praised by his parents. Instead, his father tried to persuade his son to stay in Gospić. Unbeknown to Tesla, his teachers had written Milutin warning that the boy was at risk of injuring his health by obsessively long and intense hours of study. A rift was created between father and son, perhaps in part because the Military Frontier Authority had been abolished and the scholarship was no longer available.

Reacting to the ridicule from other students, who resented Tesla for his monastic study habits and close association with the faculty, Tesla took up gambling. “He began to stay late at the Botanical Garden, the students’ favorite coffee house, playing cards, billiards and chess, attracting a large crowd to watch his skillful performances.”7 Tesla’s father “led an exemplary life and could not excuse the senseless waste of time and money…” “I can stop whenever I please,” he told his father, “but is it worth while to give up that which I would purchase with the joys of Paradise?”8

During his sophomore year, a direct-current Gramme dynamo was delivered from Paris to Professor Poeschl’s physics class. It was equipped with the customary commutator, a device that transferred the current from the generator to the motor. Electricity in its natural state is alternating. This means that its direction of flow changes rapidly. An analogous situation would be a river that flowed downstream, then upstream, then downstream, and so on many times per second.9 One can see the difficulty in harnessing such a river with, for instance, a waterwheel, for the wheel would constantly change its direction as well. The commutator is comprised of a series of wire brushes that serve to transfer the electricity into only one direction of flow, that is, a direct current (DC). It is a cumbersome device and sparks considerably.

When Professor Poeschl displayed this up-to-date equipment, Tesla intuitively deduced that the commutator was unnecessary and that alternating current (AC) could be harnessed unencumbered. He voiced this opinion, which appeared utterly fantastic at the time. Poeschl devoted the rest of the lecture to a detailed explanation of how this goal was impossible. Driving the point home, Poeschl embarrassed his student by disconnecting the “superfluous” commutator and noting with feigned surprise that the generator no longer worked.10 “Mr. Tesla may do many things, but this he can not accomplish. His plan is simply a perpetual motion scheme.”11 Tesla would spend the next four years obsessed with proving the professor wrong.

Another invention Tesla worked on at the same time, but under the tutelage of Professor Allé, was that of a mechanical flying machine. As a child, Tesla had heard stories from his grandfather about Napoleon’s employment of hot-air balloons, which were used to observe enemy troop movements and for dropping bombs. No doubt he had also studied the principles involved in school and quite possibly saw such futuristic creations floating in the Austrian skies when he went off to college.

By his third year Tesla was running into difficulties at school. Having surpassed his classmates in his studies, he became bored and frustrated by his inability to find a solution to his AC problem. He began to gamble more heavily, sometimes twenty-four hours at a stretch. Although Tesla tended to return his winnings to heavy losers, reciprocation did not occur, and one semester he lost his entire allowance, including the money for tuition. His father was fuming, but his mother came to him with “a roll of bills” and said, “Go and enjoy yourself. The sooner you lose all we possess the better it will be. I know that you will get over it.”12

The audacious youth won back his initial losses and returned the balance to his family. “I conquered my passion then and there,” he wrote, and “tore it from my heart so as not to leave a trace of desire. Ever since that time I have been as indifferent to any form of gambling as to picking teeth.”13 This statement appears to be an exaggeration, as Tesla gambled quite freely with his future and was known to play billiards when he came to the United States. An Edison employee recalled: “He played a beautiful game. [Tesla] was not a high scorer, but his cushion shots displayed skill equal to that of a professional exponent of this art.”14 It has also been suggested that years later, in the early 1890s, Tesla bilked some of the wealthy socialites in New York by feigning minimal ability in the sport.15

Exam time came, and Tesla was unprepared. He asked for an extension to study but was denied. He never graduated from the Austrian Polytechnic School and did not receive any grades for his last semester there. Most likely, he was discharged, in part for gambling and, supposedly, “womanizing.”16 According to his roommate, Tesla’s “cousins, who had been sending him money, therefore withdrew their aid.” Fearing that his parents would find out, Tesla disappeared without word. “Friends searched everywhere for him and decided that he had drowned in the river.”

Clandestinely packing his gear, Tesla traveled south, over the border into Slovenia, where he arrived in Maribor in late spring of 1878 to look for work. He played cards with the local man on the streets, as is still the custom today, and soon gained employment with an engineer “earning 60 florins a month,”17 but the job was short-lived. Tesla continued traveling, making his way through Zagreb, to the small coastal village of Min-Gag. He would not return home, for he did not want to confront his parents. At the same time, however, Tesla also continued his quest for a solution to the problem of removing the commutator from the DC generator.

His cousin, Dr. Nikola Pribic, recalled a story he had heard as a boy growing up in Yugoslavia in the 1920s: “My mother told us…he would always like to be alone [when Tesla visited us]. In the morning he would go off into the woods and meditate. He would measure one tree to another making notes, experimenting [stringing wires between them and transmitting current]. Peasants passing by would be astonished at such an erratic person…They would approach and say, ‘We’re sorry; your [cousin] seems to be crazy.’”18

Having finally located his son, after word from Kulishich, who had seen Tesla in Maribor, Milutin traveled north to discuss his academic problems. Tesla refused to return to Graz, so Milutin offered a solution: His son would make a fresh start at another university. They returned to Gospić.

Reaccepted into the family, Tesla began once again to attend church to hear his father’s sermons. There he met Anna. She was “tall and beautiful [with] extraordinary understandable eyes.” For the first and only time in his life, Tesla would say, “I fell in love.” Delighting in her company, Nikola would take Anna for strolls by the river or back to Smiljan, where they would talk about the future. He wanted to become an electrical engineer; she wanted to raise a family.19

The following year, Milutin passed away, and a few months later, in 1880, Tesla left for Bohemia (now in the Czech Republic) to “carry…out my father’s wish and continue my education.” He promised to write to Anna, but their romance was doomed, and she would marry shortly thereafter.

Tesla enrolled in the Charles-Ferdinand branch of the University of Prague, one of the foremost institutions in Europe, for the summer term.

According to Ernst Mach, who, a decade earlier, had transferred from Graz to be appointed Rector Magnificus, Prague was a city “rich in talented people,” with street signs often appearing in a half-dozen languages. Although the city was filled with majestic buildings, sanitary conditions were severely lacking. To avoid typhoid fever one had to boil water or obtain mineral water from springs to the north.20

Just two years after Tesla’s stay, Harvard psychologist William James would come to visit, to meet with Mach and Mach’s archrival, Carl Stumpf, “Ordinary Professor of Philosophy.” Stumpf was a student of the controversial ex-priest Franz Brentano (who also influenced another pupil, Sigmund Freud) and was also Tesla’s philosophy teacher. Other courses Tesla undertook included analytical geometry with Heinreich Durege, experimental physics with Karel Domalip, both “Ordinary Professors,” and higher mathematics with Anton Puchta, who was an “Extraordinary Professor” from the German Technical University also in Prague.21

With Stumpf, Tesla studied Scottish philosopher David Hume. Raised as a child prodigy of music, the acerbic and “sharp-nosed” Stumpf22 opposed a number of key psychophysicists, including the famed Wilhelm Wundt as well as Mach, but at the same time he also helped shape the thinking of a number of key students, such as phenomenologist Edmund Husserl and Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Kohler.23

A persuasive advocate of Hume’s “radical skepticism,” Stumpf argued for the concept of the “tabula rasa.” Basing his thinking on Aristotle and John Locke, both of whom repudiated the concept of innate ideas, Stumpf stated that the human mind was born a blank slate, a “tabula rasa”; impinging on it, after birth, were all of the “primary quality of things,” that is, true knowledge about the world. Through the sense organs, Tesla learned, the brain mechanically recorded incoming data. The mind, according to Hume, was nothing more than a simple compilation of cause-and-effect sensations. What we call ideas were secondary impressions derived from these primary sensations. The will and “even the soul w[ere] reduced by Hume to impressions and associations of impressions.”24 At this time, Tesla also studied the theories of Descartes, who envisioned animals, including man, as simply “automata incapable of actions other than those characteristic of a machine.”25

This line of thinking would dominate Tesla’s worldview and would ironically serve as the template for a mechanistic paradigm that would lead the inventor to discover his most original creations, even though the whole idea of original discovery appears to be antithetical to this extrinsically motivated Aristotelian premise. According to Tesla and to this view, all of his discoveries were derived from the outside world.

Although Tesla does not overtly refer to Stumpf’s perceived adversary, in retrospect, it appears obvious that Stumpf’s opposition did not stop Tesla from studying Mach’s experiments in wave mechanics. Born in Moravia (now the Czech Republic) in 1838, Mach graduated from the University of Vienna in 1860. By 1864 he was a full professor at Graz, and by 1867 he was head of the department of experimental physics at Prague, with four books and sixty-two articles to his credit. Influenced by the research in psychophysics of Fechner in Graz and Ludwig von Helmholtz in Berlin, Mach studied the workings of the human eye, along with his Prague colleague “famed physiologist and philosopher” Jan Purkyne. Both the eye and ear collected information from the outside world, analyzed it, and transferred it, via electrical impulses in the nerves, to the respective processing centers in the brain. This traditional line of research had been taken by many other well-known scientists, including Isaac Newton, Johann von Goethe, and Herbert Spencer, all favorites of Tesla’s.

In his laboratory, Mach had constructed a “famous instrument known as a wave machine. This device could make progressive [and standing] longitudinal [and] transverse waves…” Mach could display a number of mechanical effects with these acoustic waves and “demonstrate the analogy between acoustic and electromagnetic events.” By this means, the “mechanical theory of the ether” could also be demonstrated.26

By studying acoustical-wave motion in association with mechanical, electrical, and optical phenomena, Mach discovered that when the speed of sound was achieved, the nature of an air flow over an object changed dramatically. This threshold value became known as Mach 1.

Mach also wrote on the structure of the ether and hypothesized that it was inherently linked to a gravitational attraction between all masses in the universe. Influenced overtly by Buddhist writings, which no doubt filtered down to esoteric discussions by the university students, Mach could hypothesize that no event in the universe was separate from any other. “The inertia of a system is reduced to a functional relationship between the system and the rest of the universe.”27 This viewpoint was extended to the relationship of mental events to exterior influences. Like Stumpf, he agreed that every mental event had to have a corresponding physical action.28

Since Mach’s writings so closely parallel Tesla’s later research and philosophical outlook, Mach seems a curious omission from Tesla’s published writings.

By the time Tesla left the university at the end of the term, he had made great strides, both theoretical and practical, in solving the AC dilemma. “It was in that city,” Tesla said, “that I made a decided advance, which consisted in detaching the commutator from the machine and studying the phenomena in this new aspect.”29

With the death of his father, he needed to earn his own living. He began an apprenticeship in teaching but did not enjoy it. Uncle Pajo suggested that he move to Hungary, where employment could be obtained through a military friend, Ferenc Puskas, who ran the new “American” telephone exchange with his brother Tivadar.30 In January 1881, Tesla moved to Budapest, but he found to his dismay that the operation had not yet been launched.

The Puskas brothers were very busy men, running operations in St. Petersburg and overseeing, in Paris, Thomas Edison’s incandescent lamp exhibit at the Paris Exposition and fixing the lighting system at the opera house there.31 Out of funds and without a job, Tesla approached the Engineering Department at the Central Telegraph Office of the Hungarian government and talked his way into a position as a draftsman and designer. Working for a subsistence salary, he utilized what little surplus funds he had to purchase equipment to further his experiments.

Anthony Szigeti, a former classmate and engineer from Hungary, “with the body of Apollo…[and] a big head with a lump on the side…[that] gave him a startling appearance,”32 became Tesla’s friend and confidant. Many a night, when the budding inventor was not enmeshed in his research, the two fellows would meet at the local cafes, where they would discuss the events of the day or compete in such friendly games as determining who could drink the most milk. On one such occasion, Tesla claimed he was beaten after the thirty-eighth bottle!33

Due to his meager funds and general inability to budget himself, Tesla had but one suit, which had withered from use. It was the time of a religious festival, and Szigeti inquired what Tesla would be wearing. Stuck for an answer, the youthful inventor came upon the clever idea of turning his suit inside out, planning thereby to show up with a seemingly new set of clothes. All night was spent tailoring and ironing. But when one starts with a wrong premise, no amount of patching can right the problem. The outfit looked ridiculous, and Tesla stayed home instead.34

In a few months, the American telephone exchange opened there in Budapest and Tesla and Szigeti immediately gained employment. The new enterprise allowed the young engineers to finally learn firsthand how the most modern inventions of the day operated. It was also the first time that Tesla was introduced to the work of Thomas Edison, the “Napoleon of Invention,” whose improvements on Bell’s telephone helped revolutionize the field of communications. Up the poles Tesla would climb to check the lines and repair equipment. On the ground he worked as a mechanic and mathematician. There he studied the principle of induction, whereby a mass with an electric or electromagnetic charge can provide a corresponding charge or force or magnetism in a second mass without contact. He also studied a number of Edison’s inventions, such as his multiplex telegraph, which allowed four Morse-coded messages to be sent in two directions simultaneously, and his new induction-triggered carbon disk speaker, the flat, circular, easily removable device which is still found in the mouthpiece of every telephone today. As was his nature, Tesla took apart the various instruments and conceived ways of improving them. By giving the carbon disk a conical shape, he fashioned an amplifier, which repeated and boosted transmission signals. Tesla had invented a precursor of the loudspeaker. He never bothered to obtain a patent on it.

Except for friendly diversion with Szigeti, Tesla’s every spare moment was spent reworking the problem of eliminating the commutator in DC machines and harnessing AC without cumbersome intermediaries. Although a solution seemed imminent, the answer would not be revealed. Hundreds of hours were spent building and rebuilding equipment and discussing his ideas with his friend.35

He pored over his calculations and reviewed the work of others. Tesla later wrote: “With me it was a sacred vow, a question of life or death. I knew that I would perish if I failed.”36 Monomaniacal in pursuit of his goal, he gave up sleep, or rest of any kind, straining every fiber to prove once and for all that he was right and Professor Poeschl and the rest of the world were wrong. His body and brain finally gave out, and he suffered a severe nervous collapse, experiencing an illness that “surpasses all belief.” Claiming that his pulse raced to 250 beats per minute, his body twitched and quivered incessantly.37 “I could hear the ticking of a watch…three rooms [away]. A fly alighting on a table…would cause a dull thud in my ear. A carriage passing at a distance…fairly shook my whole body…I had to support my bed on rubber cushions to get any rest at all…The sun’s rays, when periodically intercepted, would cause blows of such force on my brain that they would stun me…In the dark I had the sense of a bat and could detect the presence of an object…by a peculiar creepy sensation on the forehead.” A respected doctor “pronounced [his] malady unique and incurable.” Desperately clinging to life, Tesla was not expected to recover.38

Tesla attributes his revival to “a powerful desire to live and to continue the work” and to the assistance of the athletic Szigeti, who forced him outdoors and got him to undertake healthful exercises. Mystics attributed the event to the triggering of his pineal gland and corresponding access to higher mystical states of consciousness.39 During a walk in the park with Szigeti at sunset, the solution to the problem suddenly became manifest as he was reciting a “glorious passage” from Goethe’s Faust.

See how the setting sun, with ruddy glow,

The green-embosomed hamlet fires.He sinks and fades, the day is lived and gone.

He hastens forth new scenes of life to waken.

O for a wing to lift and bear me on,

And on to where his last rays beckon.

“As I uttered these inspiring words,” Tesla declared, “the truth was [suddenly] revealed. I drew with a stick on the sand the diagrams shown six years later in my address before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers…Pygmalion seeing his statue come to life could not have been more deeply moved. A thousand secrets of nature which I might have stumbled upon accidentally I would have given for that one which I had wrestled from her against all odds and at the peril of my existence.”40

Tesla emphasized that his conceptualization involved new principles rather than refinements of preexisting work.

The AC creation came to be known as the rotating magnetic field. Simply stated, Tesla utilized two circuits instead of the customary single circuit to transmit electrical energy and thus generated dual currents ninety degrees out of phase with each other. The net effect was that a receiving magnet (or motor armature), by means of induction, would rotate in space and thereby continually attract a steady stream of electrons whether or not the charge was positive or negative. He also worked out the mechanism to explain the effect.41

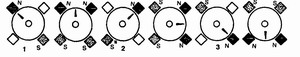

Follow the letter N in each of the stages above.

Motor Schematics Showing Magnetic Field Rotation.

Tesla referred to this diagram (or one quite similar to it) in his lecture before the American Society of Electrical Engineers for the first time in 1888. Each square represents the same armature at different points in its rotation. There are two independent circuits or currents set up diagonally across from one another which are 90 degrees out of phase with each other in both position and timing. So, for instance, in the first position, the armature points to the north pole (of the north/south circuit, which runs from bottom right to top left). The other circuit (running from bottom left to top right) is in the position of changing so that neither pole has a charge. If we look to the next square to the right (which is occurring a fraction of a second later as the currents continue to alternate), we note that the charge is beginning to enter the second circuit (i.e., running from bottom left to top right). At this point in the other circuit, the charge is beginning to reverse itself as well but still has the same polarity. As there are two north poles set up at this fraction of a second, the armature rotates to go between the two of them. In the third square, the bottom right-top left circuit is now neutralized on its way to reversing its polarity, while the bottom left-top right circuit maintains the polarity it has just entered. Therefore, the armature continues its movement to the most northward position, and so on.42

“In less than two months,” Tesla wrote, “I evolved virtually all the types of motors and modifications of the system now identified with my name…It was a mental state of happiness as complete as I have ever known in life. Ideas came in an uninterrupted stream and the only difficulty I had was to hold them fast.”43 Tesla invented, at this time, not only single-phase motors whereby the two circuits were 90 degrees out of phase with each other, but also polyphase motors which used three or more circuits of the same frequency in various other degrees out of phase with each other. Motors would be run entirely in his mind; improvements and additions to design were conceived; finally, plans and mathematical calculations would eventually be transferred to a notebook. This step-by-step procedure would become customary.

Ferenc Puskas, who had initially hired Tesla, asked if he wanted to help his brother Tivadar run the new Edison lighting company in Paris. Tesla said, “I gladly accepted.”44 Szigeti was also offered a position, so Tesla was fortunate to have a good friend with whom he could share the new adventure.

Was Tesla the first to conceive of a rotating magnetic field? The answer is no. As far back as 1824, a French astronomer by the name of François Arago experimented with spinning the arm of a magnet by using a copper disc.

The first workable rotating magnetic field similar to Tesla’s 1882 revelation was conceived three years before him by Mr. Walter Baily, who demonstrated the principle before the Physical Society of London on June 28, 1879, in a paper entitled “A Mode of Producing Arago’s Rotations.”45 The invention comprised two batteries connected to two pairs of electromagnets bolted catty-corner to each other in an X pattern, with a commutator used as a switching device. The rotating magnetic field was initiated and maintained by manually cranking the commutator. On this occasion Baily stated, “The disk can be made to rotate by means of intermittent rotation of the field effected by means of electromagnets.”46

Two years later, at the Paris Exposition of 1881, came the work of Marcel Deprez, who calculated “that a rotating magnetic field could be produced without the aid of a commutator by energizing electromagnets with two out-of-step AC currents.”47 However, Deprez’s invention, which won an award at the electrical show, had a major problem: One of the currents was “furnished by the machine itself.” Furthermore, the invention was never practically demonstrated.48

Other researchers who conceived of a rotating magnetic field analogous to Tesla’s but after his revelation (in early 1882) were Professor Galileo Ferraris of Turin, Italy (1885-88), and an American engineer, Charles Bradley (1887). Ferraris was influenced by the work of Lucien Gaulard and George Gibbs, who designed AC transformers during the mid 1880s. In 1883 they presented their AC system at the Royal Aquarium in London,49 and in 1885 they installed an AC system of power distribution in Italy, where they met Ferraris.50 Purchased by George Westinghouse for $50,000, the system was installed in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, the following year by William Stanley, Westinghouse’s head engineer. The Gaulard-Gibbs invention, however, did not do away with the commutator, which was the express purpose of Tesla’s design.

In Ferraris’s published treatise on his independent discovery of a rotating magnetic field, he wrote, “This principle cannot be of any commercial importance as a motor.” After learning of Tesla’s work, Ferraris stated, “Tesla developed it much further than [I]…did.”51

Bradley filed for a patent for an AC polyphase device on May 8, 1887 (no. 390,439) after nine Tesla AC patents had been granted. Haselwander, in the same year, utilized slip rings in place of commutators on DC Thomson-Houston equipment and also designed two- and three-phase windings on DC armatures.52

The question of priority concerning Tesla’s invention was discussed by Silvanus P. Thompson, a physics professor in London, in his 1897 comprehensive text on AC motors. Thompson (no relationship to Elihu Thomson), considered at the time to be “perhaps the best known writer on electrical subjects now living,” said that Tesla’s work separated itself clearly from predecessors and contemporaries in his “discovery of a new method of electrical transmission of power [emphasis added].”53

A question that remains unanswered was whether or not Tesla knew of Baily’s work. It is quite possible that he had read Baily’s paper, although no one at the time, including Baily, comprehended the importance of the research or understood how to turn it into a practical invention.54 Tesla stated in the early 1890s, “I am aware that it is not new to produce the rotations of a motor by intermittently changing the poles of one of its elements…In such cases, however, I imply true alternating currents; and my invention consists in the discovery of the mode or method of utilizing such currents.”55

A few years later, in a well-publicized case involving patent priorities on what came to be known as the “Tesla Alternating Current Polyphase System,” Judge Townsend of the U.S. Circuit Court of Connecticut noted that before Tesla’s invention and lecture to the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE) in 1888, there had been no AC motors; furthermore, no one attending the lecture recognized any priorities. Whereas Baily had dealt with “impractical abstractions, Tesla had created a workable product which initiated a revolution in the art.”56 The Tesla patents were also sustained against individual cases involving Charles Bradley, Mons. Cabanellas and Dumesnil, William Stanley, and Elihu Thomson.57

In citing a previous case on a similar issue, Judge Townsend responded to what today is called the “doctrine of obviousness”:

The apparent simplicity of a new device often leads an inexperienced person to think that it would have occurred to anyone familiar with the subject, but the decisive answer is that with dozens and perhaps hundreds of others laboring in the same field, it had never occurred to anyone before [Potta v. Creager, 155 U.S. 597]…Baily and the others [e.g., Bradley, Ferraris, Stanley] did not discover the Tesla invention; they were discussing electric light machines with commutators…Eminent electricians united in the view that by reason of reversals of direction and rapidity of alternations, an alternating current motor was impracticable, and the future belonged to the commutated continuous current…

It remained for the genius of Tesla to…transform the toy of Arago into an engine of power.58

The discovery of how to effectively harness the rotating magnetic field was really only a fraction of Tesla’s creation. Before his invention, electricity could be pumped approximately one mile, and then only for illuminating dwellings. After Tesla, electrical power could be transmitted hundreds of miles, and then not only for lighting but for running household appliances and industrial machines in factories. Tesla’s creation was a leap ahead in a rapidly advancing technological revolution.