28

THE HERO’S RETURN (1900)

Common people must have rest like machinery but the great old Nick—the Busy One—see him go 150 hours without food or drink. Why he can invent with his hands tied behind his back! He can do anything, in short, he is superior to all laws of hygiene and human energy. He is a vegetarian that doesn’t know how to vegetate…

ROBERT UNDERWOOD JOHNSON1

On January 7, 1900, Tesla left Colorado Springs with every intention of returning. Engaging C. J. Duffner and another watchman to look after the laboratory, the inventor departed with inexplicit promises for future payment. His funds exhausted, he also left without covering outstanding bills he had incurred with the local power company.2

The Johnsons were thrilled with the wizard’s return, and they celebrated in grand style by dining out. With Gilder’s approval, Robert suggested that Tesla compose a discourse on his recent endeavors.

Coincidentally, Marconi was in Manhattan seeking investors and planning on lecturing on his progress in wireless.3 “When I sent electrical waves from my laboratory in Colorado, around the world,” Tesla reported, “Mr. Marconi was experimenting with my apparatus unsuccessfully at sea. Afterward, Mr. Marconi came to America to lecture on this subject, stating that it was he who sent those signals around the Globe. I went to hear him, and when he learned that I was present he became sick, postponed the lecture, and up to the present time has not delivered it.”4

Although fearful of Tesla, Marconi was also desirous of obtaining a greater understanding of the master’s equipment. With Michael Pupin as intermediary, Marconi was introduced to Tesla at the New York Science Club.5 Pupin was in exceptionally high spirits, as John S. Seymour, commissioner of patents had finally retired. After six years of submissions, in his attempts to try and prove that his understanding of resonance and harmonics in the field of AC transmission superseded Tesla’s, he had finally won. In December 1899 he applied once again for his patent, “The Art of Reducing Attenuation of Electrical Waves,” and the new commissioner, Walter Johnson, sanctioned it.6 Apparently just one month later, the trio left after dinner to visit Tesla’s lab. George Scherff was working late and greeted them at the door.

“I remember [Marconi] when he was coming to me asking me to explain the function of my transformer for transmission of power to great distances,” Tesla recalled. Although the inventor obviously had mixed feelings about the meeting, he nevertheless obliged with a discourse on the difference between Hertzian radiations and Tesla currents. “Mr. Marconi said, after all my explanations of the application of my principle, that it is impossible.”

“Time will tell, Mr. Marconi,” Tesla shot back.7 Pupin was able to usher Marconi to the door before discussions became more heated.

“I understand completely what you are doing, Mr. Marconi,” Pupin began as he walked the young Italian back to his hotel. “I would like very much to act as a consultant in your operation.”

“That would be an honor,” Marconi said as he discussed with Pupin a way to “persuade Signor Edison to come aboard.” Marconi’s reason, in particular, was to obtain Edison’s grasshopper patent, which described a wireless way for jumping messages from train stations to moving trains and which Edison patented in the 1880s.

Pupin was elated. Not only was he becoming professionally involved in an exciting international wireless enterprise; he had also begun to cash in on his new AC patent. In June, Pupin received a $3,000 advance for selling the rights to John E. Hudson, president of AT&T, and a few months later he negotiated for yearly payments of $15,000 per year, for an amount totaling $200,000 for the invention Commissioner Seymour called “tautological” and “no more…than a multiplication of Tesla’s circuit [that utilized principles] well understood in the art.”8 In either case, the patent enabled AT&T to perfect long-distance telephone transmissions and provided Pupin with a handsome income for many years to come. It also vindicated his position that he had understood Tesla’s invention better than Tesla did.

Tesla tried again to interest the submarine designer John Holland in telautomatics; he also worked to fashion “dirigible wireless torpedoes” or small airships which could be controlled from the ground. “Everybody who saw them,” he revealed a few years later, “was amazed at their performance.”9

After putting together a prospectus and conferring with his lawyers, the inventor packed his bags for Washington to speak in person with Admiral Higginson of the Light House Board and Secretary John D. Long of the navy. He planned not only to offer his “devil telautomata” but also a scheme for “establish[ing] wireless telegraphic communication across the Pacific.” Met with ridicule and skepticism, the inventor was shuffled into what Mark Twain called “the circumlocution office.” “My ideas,” Tesla said, “were thrown in the naval waste basket…Had only a few ‘telautomatic’ torpedoes been constructed and adopted by our navy, the mere moral influence of this would have been powerfully and most beneficially felt in the present Eastern complication [the Japanese war with Russia].”10

Tesla had hoped at least that the U.S. Coast Guard or Navy would come through on a smaller scale by financing the construction of modest-sized transmitters for their lighthouses and ships, but the agencies dodged any serious commitment and continued to hide behind a bureaucratic quagmire involving the need for congressional approval.11

“I’ve circumscribed the globe with electrical impulses,” he told Scherff upon his return. “Let them have the Hertzian dabblers. They’ll come back around my way soon enough.”

“What will you do with Professor Pupin, stealing your work in alternating current?”

“He’s involved in sending voice over wires,” the inventor replied. “Who can be bothered.”

It was at this time that Tesla commissioned an agent in Britain to locate an appropriate place for constructing a receiving station,12 as he continued to rework blueprints for his transoceanic broadcasting system. Using his English royalties as collateral, he asked George Westinghouse for a loan of a few thousand dollars; he also tried to interest him in the wireless enterprise.13

Westinghouse, however, declined to get involved, but he did advance the inventor the requested funds, even though his company had overextended themselves nearly $70 million in their rapid expansion and changeover to the polyphase system. Incessant legal fees due to the never-ending litigation on patent priority battles, mostly with the countless subsidiaries were also a great drain. Swiss emigrant B. A. Behrend, author of one of the early standard textbooks on AC motors, wrote in his treatise that much to the chagrin of New England Granite’s (a GE subsidiary) patent attorney, he refused to testify against Tesla, “as such evidence would be against [his] better convictions.”14

This letter was written in 1901, a full year after Judge Townsend’s unequivocal ruling vindicated Tesla as the sole author of the AC polyphase system (see chapter 3).15 Now Westinghouse could finally begin to collect damages and pay back its enormous debt. George Westinghouse sent Tesla a thank you note congratulating himself “for winning the suit” and congratulating Tesla for being “awarded the credit for a great invention.” Westinghouse ended the letter as follows “You know I appreciate your sympathetic interest in my affairs.”16

In the early part of 1900, Tesla filed for three patents related to wireless communication.17 He made several attempts to contact the elusive Colonel Astor but concentrated most of his efforts on working on an article for the Century. Robert had requested that Tesla write an educational piece about telautomatics and wireless communication. The plan was to decorate the essay with photographs of the remote-controlled boat and the inventor’s fantastic experiments in Colorado, but Tesla had other ideas. Influenced by Western philosophers Friedrich Nietzche and Arthur Schopenhauer about such ideas as the creation of the Übermensch through activation of the will and renunciation of desire and by Eastern philosophers such as Swami Vivekananda on the link between the soul and Godhead, Prâna (life force) and Akâsha (ether) and its equivalence to the universe, force, and matter,18 the inventor decided to compose a once-in-a-lifetime apocalyptic treatise on the human condition and technology’s role in shaping world history.

Robert pleaded with him “not to write a metaphysical article, but rather an informative one,” but Tesla would not listen. Instead, he sent back a twelve-thousand-word discourse which covered such topics as the evolution of the race, artificial intelligence, the possibility of future beings surviving without the necessity of eating food, the role of nitrogen as a fertilizer, telautomatics, alternative energy sources (e.g., terrestrial heat, wind, and the sun), a description of how wireless communication can be achieved, hydrolysis, problems in mining, and the concept of the plurality of worlds.

Robert was now in a bind. Neither he nor Gilder wanted to publish a lengthy, controversial, abstract philosophical essay which might damage the magazine. However, they could not simply cross out sections they were unhappy with, for they were dealing with a man who was born a genius and a friend who had contributed two previous gems that added greatly to the prestige of their publication. How to approach the hypersensitive savant was a difficult problem which Robert did not relish.

March 6, 1900

Dear Tesla,

I just can’t see you misfire this time. Trust me in my knowledge of what the public is eager to have from you.

Keep your philosophy for a philosophical treatise and give us something practical about the experiments themselves…You’re making a task of a simple thing and for all I have said, forgive my clumsy way of saying it because of my love and respect for you, and because I have had nearly 30 years of judging what the public finds interesting.

Faithfully yours,

(believe me never more faithfully)

RUJ19March 6, 1900

My dear Robert,

I heard you are not feeling well and hope that it is not my article that makes you sick.

Yours sincerely,

N. Tesla20

Tesla knew what he was doing. He had decided, once and for all, to put down a significant percentage of the knowledge he had amassed into one treatise, and there was no way he was going to change it. Most likely Robert conferred with Gilder. Clearly, the essay was brilliant and original, and the more they read it, the more they realized its many layers of wisdom. The best tack to take at this point, they reasoned, was to work to clarify the piece by using subheadings, by including all of the startling electrical photos from Colorado, and the telautomaton, and by having Tesla more carefully explain the details of his inventions, and then hope for the best. The published essay began as follows:

The Onward Movement of Man

Of all the endless variety of phenomena which nature presents to our senses, there is none that fills our minds with greater wonder than that inconceivably complex movement which, in its entirety, we designate as human life. Its mysterious origin is veiled in the forever impenetrable mist of the past, its character is rendered incomprehensible by its infinite intricacy, and its destination is hidden in the unfathomable depths of the future.

Inherent in the structure matter, as seen in the growth of crystals, is a life-forming principle. This organized matrix of energy, as Tesla comprehended it, when it reaches a certain stage of complexity, becomes biological life. Now, the next step in the evolution of the planet was to construct machines so that they could think for themselves, and so Tesla created the first prototype, his teleautomaton. Life-forms need not be made out of flesh and blood.

As an environmentalist, Tesla was concerned about personal hygiene, air and water pollution, and the needless waste of natural resources. Through concentration on energy problems, solutions could be achieved. Thus, many of Tesla’s inventions were created specifically to maximize efficient use of energy and prove out the principle that a self-directed thinking machine could alter the course of civilization by gaining greater control over the evolution of the planet.

In the middle of the treatise, the inventor explained in vivid detail the mechanism behind his wireless transmitter. Numerous photographs of his experiments at Colorado Springs also enhanced the impact of the message. Thirty-five pages later, he ended the treatise with a discussion of the cognitive hierarchy and the speculation that “intelligent beings on Mars…if there are [any]” most likely utilize a wireless energy-distribution system that interconnects all corners of their planet. Tesla concluded: “The scientific man does not aim at an immediate result. He does not expect that his advanced ideas will be readily taken up. His work is like that of the planter—for the future. His duty is to lay the foundation for those who are to come, and point the way.”21

When the article appeared in the June issue of the Century, it created a sensation. Tesla circulated advance copies to friends, such as Mrs. Douglas Robinson, one of the founders of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,22 Julian Hawthorne, Stanford White, and John Jacob Astor. In Astor’s case, Tesla included his wireless patent applications, forwarding “this matter to your home, instead of your office [for secrecy reasons]…The patents give me an absolute monopoly in the United States not only for power purposes,” the inventor continued in another letter to the colonel, “but also for establishing telegraphic communication…no matter how great the distance.”23 Those who were Tesla supporters rallied around him, Nature gave it a “favorable response,” and the French quickly translated it for their readers,24 but those who were against him now had a new supply of ammunition for a frontal assault.

The stage was set in March 1900, when Carl Hering was elected president of the AIEE; Professor Pupin was a close second.25 Hering, who would also become editor in chief of Electrical World & Engineer, set a new tone for the electrical community. Just as he had called into question Tesla’s priority work on AC a decade before, when he had backed Dobrowolsky, he also challenged Tesla’s credibility in the field of wireless. Other opponents included Reginald Fessenden, who was trying to obtain competing patents on tuned circuits, and such traditional rivals as Lewis Stillwell, Charles Steinmetz, Tom Edison, and Elihu Thomson. The first potshots appeared in the Evening Post26 and then in Popular Science Monthly.

Tesla had suggested that the sum total of human energy on the planet, which he called M, could be multiplied by its “velocity,” V, which was measured by technological and social progress. Just as in physics, the total human force could be calculated as MV2. If humans go against the laws of religion and hygiene, the total human energy would diminish. In a primitive or agrarian-based society the energy would progress arithmetically. However, if the new generation had a “higher degree of enlightenment,” then the “sum total of human energy” would increase geometrically. Tesla was suggesting that with his inventions of the induction motor, AC power transmission, and his remote-controlled robots, human progress would evolve at ever increasing rates.

In a highly visible discourse under the banner title “Science and Fiction,” an anonymous writer with the nom de plume “Physicist” vehemently attacked this premise. “Unhappily,” this critic wrote, “Mr. Tesla in his enthusiasm to progress…neglects to state which direction is the proper one for the human mass to follow, north, south, east, west, toward the moon or Sirius or to Dante’s Satan in the centre of the earth…Of course, the whole notion…is absurd.”

The editorial, which continued for six columns, called into question Tesla’s invention of the telautomaton, his belief that fighting machines would replace soldiers on the field—“international bull-fights…or potatoraces might do just as well”—his work in wireless, and his support for the plurality of worlds hypothesis. The author suggested that the Century, in future issues, should subject these types of articles to a scientific board “for criticism and revision if only for the protection against bogus inventions and nonsensical enterprises.” Hurling epithets as if in combat with a mortal enemy, “Physicist” concluded, “The editors [of the Century] apparently impute to their readers a desire to be entertained at all costs…They evidently often do not know science from rubbish and apparently seldom make any effort to find out the difference.”27

The onslaught continued in Science and in a follow-up editorial again in Popular Science Monthly, this time by a mysterious “Mr. X.”

“Science (Pseudo) contains an article from xxx. ‘Physicist’ is not in it,” Tesla wrote to Johnson, adding sarcastically, “It is also highly complimentary to the editors of your great magazine.”28 Other daily papers also attacked the inventor’s controversial claims.

Tesla, however, maintained a blind eye to this credibility problem and audaciously or foolheartedly followed up this article with the infamous piece “Talking With the Planets” in Colliers, which we reviewed in an earlier chapter. Making no secret of his identity, Reginald Fessenden, who was now embroiled in a legal dispute with Tesla, vehemently wrote in Hering’s journal that the source of “the so-called Martian signals have long been known…and only the crassest ignorance could attribute any such origin.” Having at one time been “a serious obstacle to multiplex systems, [they are now all but] eliminated.” Fessenden said the signals were due to “street cars, lightning flashes and the gradual electriciation of the aerial. Furthermore, the different kinds are easily distinguishable. Those ignorant of the subject might mistake them for intelligent signals.”29

Ever since his return to New York, Tesla made repeated efforts to rekindle his friendship with Astor, but the gadabout was proving difficult to corner. Over the summer, the Johnsons tried to woo the inventor to Maine for a vacation, but he was too intent on contacting the multimillionaire.

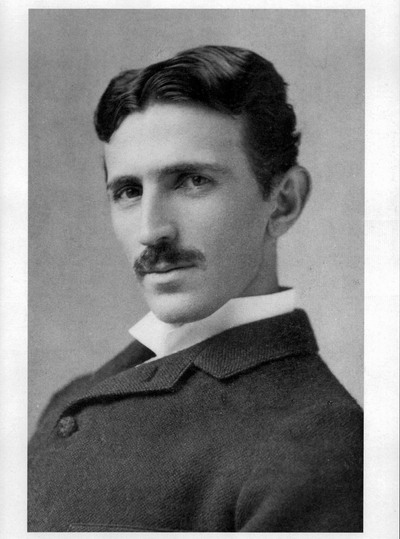

Nikola Tesla at the height of his fame in 1894

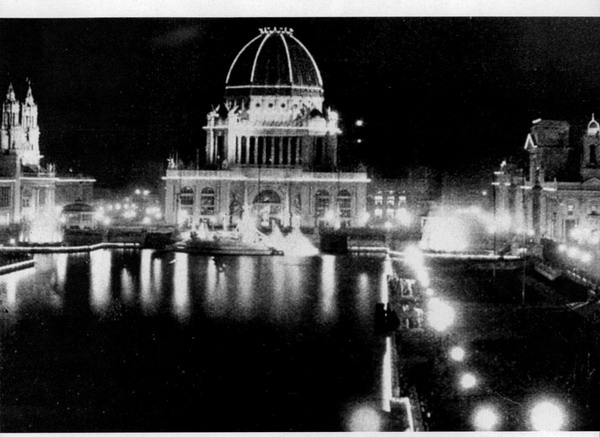

Above The Chicago World’s Fair at night, illuminated by Westinghouse Corporation utilizing the Tesla AC polyphase system.

(Opposite above) Tesla displaying wireless fluorescent tubes before the Royal Society in England, 1892.

(Opposite below) Thomas Edison (center) at his Menlo Park invention factory. Seated to Edison’s left is Charles Batchelor, key partner and the man who introduced Tesla to Edison, probably in France in 1883.

(Right) Thomas Commerford Martin, editor of the 1893 text The Inventions, Researches, and Writings of Nikola Tesla, the only collected works produced during Tesla’s lifetime. (MetaScience Foundation)

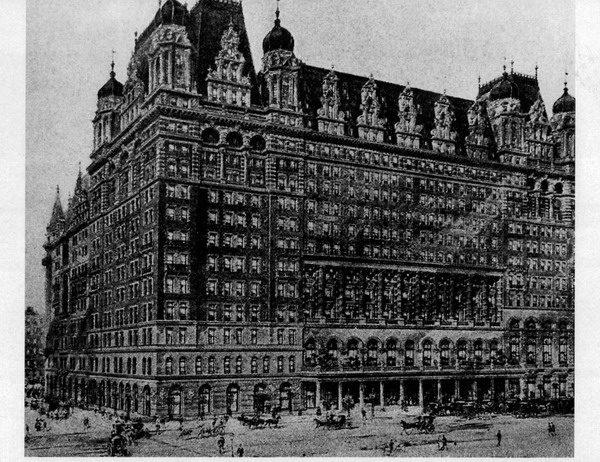

(Above) The Waldorf-Astoria, where Tesla lived from 1897 to 1920. (MetaScience Foundation)

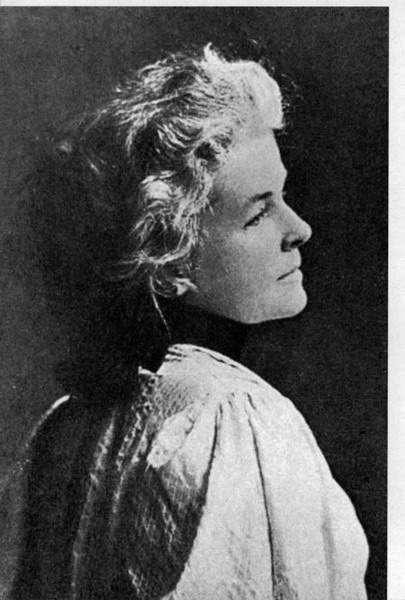

(Left) Katharine Johnson, who had a long-standing platonic love affair with the inventor. (Little Brown)

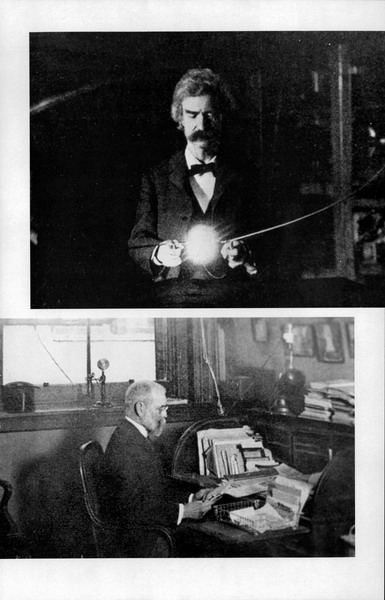

(Opposite above) Mark Twain in Tesla’s laboratory in 1894. (MetaScience Foundation

(Opposite below) Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century magazine and one of Tesla’s closest friends. (Little Brown)

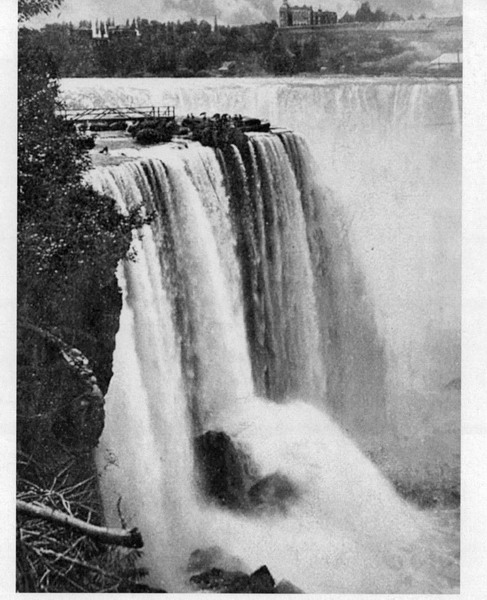

(Right) Niagara Falls at the turn of the nineteenth century.

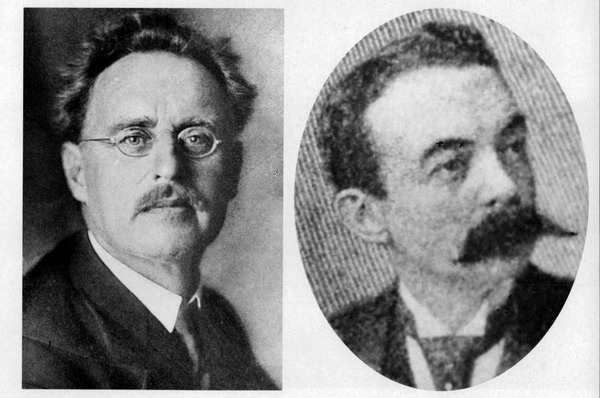

(Below right) Edward Dean Adams, one of Tesla’s financial backers and the man responsible for the Niagara Falls hydroelectric project. (MetaScience Foundation)

(Below left) C. E. L. Brown, an important Tesla supporter and the first engineer to transmit AC polyphase currents over long distances. (MetaScience Foundation)

(Above) The patent plaque at Niagara Falls, listing Tesla as the primary inventor of the AC polyphase system. (Marc J. Seifer)

(Left) Charles Steinmetz, initially a Tesla supporter and then one of the inventor’s most vigorous opponents throughout their lifetimes. (MetaScience Foundation

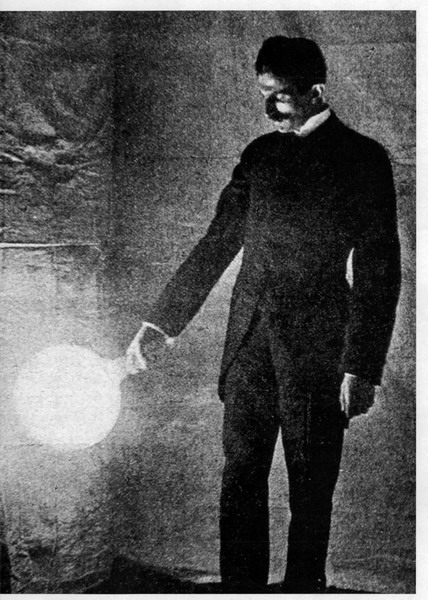

Nikola Tesla displaying his invention of the cold wireless lamp without filament. (Electrical Review, 1898).

August 2, 1900

Dear Mr. Tesla,

I have been thinking of you all day and all evening as I do so often…I sat on a little hillside this afternoon looking over green meadows to the sea beyond…and wishing that I could loan you my eyes that you might have my visions and drink in the beauty of the day…You are as silent as only you know [how] to be…Do call us.

Yours faithfully,

Katharine Johnson30August 12, 1900

My dear Mrs. Johnson,

Just a line to tell you that I never can and never shall forget the Filipovs—they have given me too much trouble.

Yours sincerely,

N. Tesla31

Unable to relax until he settled things with Astor, Tesla tried again, having forfeited the chance for a needed respite.

August 24, 1900

My dear Colonel Astor,

I still remember when you told me, that if I could only show you great returns on your investment, you would gladly back me up in any undertaking, and I hope not in a selfish, but in a higher interest that your ideas have not changed since…[Re: oscillators, motors and lighting system] not less than $50,000,000 [can be]…made out of my invention. This may seem to you exaggeration, but I honestly believe that it is an understatement.

Is it possible that you should have something against me? Not hearing from you I cannot otherwise interpret your silence…

Finally, Astor replied, stating that he was “glad to get your letter, and will get back to you.”32 But this was really a decoy procedure, for Astor continued to slip away. Tesla shot off another round of letters outlining his progress with his oscillators, fluorescent light—“the commercial value…if rightly explored, is simply immense”—and wireless enterprise,33 but again Astor balked.

Astor never directly told Tesla his real feelings. His reluctance in advancing the partnership suggests that he was angry with Tesla for not exploiting the oscillators and fluorescent lights in 1899, as he had promised, but had instead run off to Colorado Springs to conduct his wireless folly.

Certainly the onslaught in the papers injured Tesla’s reputation, but it is this author’s belief that the attack by the press had little if anything to do with Astor’s turnabout. Tesla had deceived him. As wealthy as he was, Astor wanted to invest in a sure thing. The oscillators and the fluorescent lights seemed practically ready for market, but rather than perfect these inventions, Tesla took the capital to go off on another venture and returned without a dime. Astor was enraged but too much of a gentleman to even let Tesla know. With Stanford White and Mrs. Douglas Robinson behind him, Tesla explored a fresh lead.