33

WARDENCLYFFE (1902-1903)

While the tower itself is very picturesque, it is the wonders hidden underneath it that excite the curiosity of the little [hamlet]. In the centre of [the] base, there is a wooden affair very much like the companionway on an ocean steamer. Carefully guarded, no one except Mr. Tesla’s own men have been allowed as much as the briefest peep…

Mr. Scherff…told an inquirer that the [shaft entrance] led to a small drainage passage built for the purpose of keeping the ground about the tower dry; [but] the villagers tell a different story.

They declare that it leads to a well-like excavation as deep as the tower is high, with walls of masonwork and a circular stairway leading to the bottom. From there, they say. the entire ground below has been honeycombed with subterranean [tunnels that extend in all directions].

They tell with awe how Mr. Tesla, on his weekly visits…spends as much time in the underground passages as he does on the tower or in the handsome laboratory where the power plant for the world telegraph has been installed.

NEW YORK TIMES1

Just as Tesla had created a notebook for his experiments in Colorado, he also compiled a daily log of activities at Wardenclyffe. His records for 1902 reveal little activity for the first third of the year except for the month of March. Extended note taking really began again in May and continued uninterruptedly until July 1903. Each week, Tesla watched the tower attain a new height as he experimented by measuring the capacitance of his apparatus and constructing a prototype planet to calculate “his theory of current propagation through the Earth.” On this sizable metal sphere, the inventor would transmit varying frequencies to measure the voltage, wavelength, and velocity of the transmitted energy and also assess various nodal points, such as along the equator and at the pole opposite the point of generation.2

In February 1902, along with Stanford White, Tesla entertained Prince Henry of Prussia who had come to New York to retrieve a royal yacht that had been built in America. The brother of Kaiser Wilhelm, it had been Prince Henry who had assisted in the performance of the inventor’s famous experiments under Tesla’s name in Berlin six years earlier. The yacht was being christened by Alice Roosevelt, daughter of the president.3 In June out at Wardenclyffe, “two grey-haired East Hampton pilgrims drop[ped] in on their way to a Spring retreat.”4 Kate’s eyes glowed as she broke off from Robert and Nikola to approach the tower and feel it with her own hands. A radiant warmth flowed through her being as she watched the lanky engineer converse with her husband.

By September, the transmitter had reached its full elevation of 180 feet. Exhausted of funds, with still the dome to place on top, the inventor had no choice but to wind down activities and lay off most of the workers. Tesla had sold his last major asset, a $35,000 land holding, but even that could not keep the operation fully afloat. Nevertheless, with this new source of revenue, he procured enough funds to keep a skeleton crew, cover Scherff’s and his own lodging, and pay for a chef from the Waldorf to come out at regular intervals. Tesla also took this time to photograph the interior operations of his entire plant. These pictures not only included reproductions of all his machinery but also contained a representative sample of the myriad different types of radio tubes that the inventor had designed. They numbered nearly a thousand.5

The Port Jefferson Echo reported “War between Marconi and Tesla” in their headlines in 1902. According to the paper, the United States Marconi Company had purchased land west of Bridgehampton and was planning on constructing its own competing 185-foot tower, with New York City connections to Western Union. “It should become the most important wireless center in the country.” Whereas Marconi was going to send his signals through the air, the paper said, Tesla plans, through his “500-foot deep” shaft, to send messages through the earth as well. Though the hollow was 120 feet, the gist of the report was accurate.

Having first sent an emissary, Marconi himself hired a horse and buggy one rainy morning to go out to Wardenclyffe to meet with Tesla and see the operation with his own eyes.6 Marconi’s limitations became apparent in conversation, and this gave Tesla the courage to return to see Morgan. He had stayed out of Morgan’s way for nearly a year, but now it was clear to the inventor that once his partner realized the work accomplished with so little funds at hand, he would reconsider his position and agree to resume investment. All the inventor had to do was change the man’s mind.

On September 5, Tesla wrote the financier to inform him that the foreign patents had been assigned to the company. The letter explained clearly that his wireless system ensured privacy and had the ability to create a virtually infinite number of separate channels that were dependent not only on particular combinations of differing frequencies but also on “their order of succession.” In essence, the inventor had explained to Morgan the concepts inherent in such devices as the protected channels on cable TV, digital recording, and the wireless telephone scrambler.

In the letter, Tesla explained that he was forced to increase the power of his apparatus because of “bold appropriations” of his equipment (Marconi’s piracy), but his mea culpa also betrayed paranoid tendencies, even though he was attempting reconciliation: “The only way to fully protect myself was to develop apparatus of such power as to enable me to control effectively the vibrations throughout the globe. Now, if I had received this necessity earlier, I would have gone to Niagara, and with the capital you have so generously advanced, I could have accomplished this easily. But unfortunately my plans were already made and I could not change. I endeavored once to explain this to you, much to my sorrow, as I impressed you wrongly. Nothing remained then but to do the best I could under the circumstances.”

Morgan’s response was utter astonishment. Tesla had not only reiterated the breach of contract but had also revealed a striking flaw in his plan. Whereas he would have to haul in continuing truckloads of coal to provide the energy required to fire up his transmitter on Long Island, if he had set up operations at Niagara, there would have been easy access to unlimited amounts of power, and thus the operation would have been considerably less expensive to initiate. Furthermore, there was a standing offer by Rankine and his associates to provide power at the Falls for little or no cost, thereby reducing potential expenses even more. Nevertheless, Tesla incredibly informs Morgan that even on Long Island he could outdo the power of the giant cataract.

“By straining every part of my machinery to the utmost,” Tesla wrote, “I shall be able to reach…a rate of energy delivery of 10 millions of horse power.” This production, he proclaimed, would be equal to “more than twice that of the entire Falls of Niagara. Thus the waves generated by my transmitter will be the greatest spontaneous manifestation of energy on Earth…the strongest effect produced at a point diametrically opposite the transmitter which in this instance is situated a few hundred miles off the western coast of Australia.”

Whether or not this statement was true, it was counterproductive to divulge this. (Most likely Tesla is discussing the production of a single massive burst of electrical energy rather than a continuous, never-ending flow. In either case, having spent a year in the outbacks of Colorado, the bon vivant was not about to give up his lifestyle at the elegant Waldorf for another lonely excursion to the dreary location near Buffalo.) Neurotically impelled , the inventor was stirred to impress the financial magnate when all Morgan wanted was to signal ocean liners and send Morse code to Europe.

Later in the letter the inventor did address this more modest task of broadcasting simple messages. Over transmission lines, dispatches from New York Telegraph & Cable could be delivered to Wardenclyffe, where they could then be distributed to Europe by means of wireless to a central receiving station.

Since your departure, Mr. Morgan, I have had time to reflect…[on] the importance and scope of your work, and I now see that you are no longer a man, but as a principle and that every spark of your vitality must be preserved for the good of your fellowmen. I have therefore given up the hope that you might aid me in establishing a manufacturing plant which would enable me to reap the fruit of my labors of many years. But some ideas which I have not simply conceived—but worked out—are of such great consequence that I honestly believe them to deserve your attention…

I have no greater desire than to prove myself worthy of your confidence, and that to have had relations, however distant, with so great and noble man as you will ever be for me one of the most gratifying experiences and most highly prized recollections of my life.

Yours most devotedly,

N. Tesla7

Perhaps it was the finale or the inventor’s rank or maybe the realization of the value of the fundamental patents that continued to flow into his office, but for whatever reason, Morgan was moved to the point of allowing another meeting—as long as it was expressly understood that the liaison would still be kept unpublicized.8

Tesla’s plan was to seek new investors by selling bonds and capitalizing the company at $10 million. What he did not realize was that his silent partner wanted to maintain his 51 percent control over the patents, take in “about  of the securities,” and also be reimbursed for his initial investment.9 In other words, whereas Tesla required about an additional $150,000 to complete the tower, pay off his debts, construct the receiving equipment, and so on, the Wall Street hydra wanted his money back in full, wanted to maintain his large share of the concern, wanted the inventor to raise the funds on his own, and wanted no one to know of his connection to the project! If Tesla were to agree to all that, they would have a deal.

of the securities,” and also be reimbursed for his initial investment.9 In other words, whereas Tesla required about an additional $150,000 to complete the tower, pay off his debts, construct the receiving equipment, and so on, the Wall Street hydra wanted his money back in full, wanted to maintain his large share of the concern, wanted the inventor to raise the funds on his own, and wanted no one to know of his connection to the project! If Tesla were to agree to all that, they would have a deal.

Kate gazed out her window at the changing colors of the leaves as she went over the Thanksgiving menu with Agnes.

“Do you think he’ll come, Momma?”

“Of course he will.”

“He didn’t last year.”

“Mr. Tesla was not himself,” Katharine stated matter-of-factly. Sitting by a fizzling Edison lightbulb, she penned an urgent notice and hired a special messenger to deliver it.

Tesla was working on his list of prospective investors when a loud banging at his door interrupted him. “Sorry, sir, it is important.”

The inventor grabbed the letter and ripped it open. Thoughts of accident and death flashed through his brain as he reflected upon his relationship with the Johnsons and his inability to deal with them now. He wrote back:

Some day I will tell you just what I think of people who mark their letters “important” or send dispatches at night.

You know I would travel 1000 miles to have such a great treat as one of Mrs. Filipov’s dinners, but this Thanksgiving day I have a great many hard nuts to crack and I will pass it in quiet meditation. The rest of the holidays I propose to pass in the same good company.

Never mind my absence in body. It is no consequence. I am with you in spirit.

With love to all and Agnes in particular,

Nikola10

With this painful letter, Tesla succeeded in transferring some of his anguish to his friends. Not only would he not attend the November holiday feast; he would also not partake of the Christmas festivities. Unable to escape himself or dig his way out of the deep hole he was in, he passed the time cranking out ways to enlist new investors.

When Katharine realized the depth of the inventor’s despair, she became alarmed. The emptiness at such an important occasion was almost too much to bear. “Agnes, please write Mr. Tesla once again and tell him that he may stop by at any time that he likes, and forever long he wants.”

“Don’t you think he knows what he is doing,” Robert interrupted. “He needs to be by himself right now.”

“Don’t tell me what he needs!” Kate exploded, her Irish temper flaring. “Do it,” she commanded her daughter. Robert moved quietly into the living room to read a book of poems.

As Agnes sat down to write, a peculiar dark and twisted expression passed over her mother’s face. Kate retired to her boudoir to sit there in her gloom. Tesla wrote, “My dear Agnes,” back two days after the new year. “I have no time but plenty of love and friendship for all of you. I would like very much to see you, but it is impossible. Even kings are beginning to infringe my patent rights, and I must restrain myself.”11

Katharine could take solace in the fact that her platonic aficionado had used the word love twice in two letters. In his own peculiar way, he had transformed the pain of his career to their linkage, and in that sense, he had reached out, as never before, but it was by withdrawing, and this made her love him more.

Thomas Commerford Martin may have had mixed feelings about having supported so vigorously a man he knew had infringed on Tesla’s patents, but Martin had warned Tesla nearly five years earlier that whereas Marconi was succeeding on the physical plane, Tesla appeared to advance mostly in theory. A social gadfly, Martin had also upped his prestige considerably by hosting the gala Marconi affair, and he continued to elevate his standing among the upper echelon of the electrical community. Harper’s decided to do a feature on him, and Edison was becoming amenable to the idea of allowing him to write his biography.12 As a precursor to the new venture, the editor prepared for the weekly a short piece on the “volcanic lifetime of a master who has produced a patent every fortnight for over thirty years.”

An “Edison Man” remains an Edison man to the end of the chapter, and is proud of the stamp left upon his career by the great spirit with whom trials and triumphs have been shared…[Although] Edison has always been surrounded by a willing host of workers, [he] has always held easily his leadership among them. This is by no means true of other[s]…Some powerful thinkers, whether from instinctive distrust or unavowed jealousy, endeavor to hammer out their conceptions in lonely struggle, and names could be mentioned here of electrical inventors whose curse seems to be this sterile seclusion. In Edison’s case, the sunny, kindly temperament of the man makes for friendship.13

Martin was almost certainly talking about Tesla here, and in so doing, he highlighted ponderous debilities in the inventor’s personality. Tesla could be inordinately withdrawn, private, “distrustful,” an elitest, and yet envious of others, unable to share in the development of his ideas lest he would have to share credit. Later in this article, Martin wrote that “a great many first-class inventors are sharply concentrated along one line,” while Edison had “many irons in the fire.” As versatile and incredibly prolific as Tesla was, he stuck, until the end of his days, to the single monumental Wardenclyffe idea when any aspect of the grand plan, in and of itself, would have been a revolutionary accomplishment.

Underneath it all, however, Martin was, without doubt, the one individual who had accomplished the most toward explicating the wondrous achievements of the sequestered genius, and his connection to Tesla would remain sacred to him for the duration of his life. Martin took the opportunity to let Tesla know this when he gave the inventor an updated version of the collected works.

“Many thanks for the book,” Tesla wrote his old-time friend. “It was a pleasure to read the dedication which tells me that your heart is true to Nikola.”14 This occasion served to break the ice again, and the two resumed their friendship, albeit not with the same intensity as before.

In a dreadful predicament, the inventor was beginning to stare down a canyon of doom, writing his letters now in pencil, abandoning the certainty of the pen.

Ever since I was a boy I was desirous of drawing on the Bank of England. Can you blame me? I confess my low commercial interests dominate me…Will you please give me a list of people almost as prominent and influential as the Johnsons who desire to get into high society. I will send them my letter.

Nikola Busted15

Forced to approach both the Johnsons and his manager, George Scherff, for funds, both lent him thousands over the next few years.16 Simultaneously, he returned to former enthusiasts such as Mrs. Dodge and Mrs. Winslow, and new investors, such as Mrs. Schwarz, wife of toy store owner F. A. O. Schwarz.17 The price for investment was $175 for each share.

With his back to the wall, he approached again his Wall Street benefactor. “Will you now let me go from door to door to humiliate myself to solicit funds from some jew or promoter and have him participate in that gratitude which I have for you?,” he wrote Morgan. “I am tired of speaking to pusillanimous people who become scared when I ask them to invest $5000 and get the diarrhoea when I call for ten.”18

MAD SCIENTIST

“It is a mighty fine tower,” said one good farmer…last week. “The breeze up there is something grand of a Summer evening, and you can see the Sound and all the steamers that go by. We are tired, though, trying to figure out why he put it here instead of Coney Island.”19

Although operations were suspended, there were many avenues the inventor would explore in his attempts to complete the vision. One of his first decisions was to comply with George Scherff’s plan to become more pragmatic. Throughout the balance of the year and much of 1903, Tesla began to manufacture oscillators and continue development of his fluorescent lamps. Revenues began to trickle in, and by midyear he had compiled enough savings to hire back a half-dozen workers and pay for the cupola, which was placed at the apex of the spire.20 Over fifty feet in diameter, ten feet tall, and weighing fifty-five tons, this iron-and-steel crown, with its specially designed multitude of nodal points, would serve the purpose of storing electrical charges and distributing them either through the air or down the metal column and into the hollow. The cupola was linked to four large condensers behind the laboratory, which also served the purpose of storing electrical energy, and these in turn were coupled with “an elaborate apparatus” which had the ability to provide “every imaginable regulation…in the control of energy.”

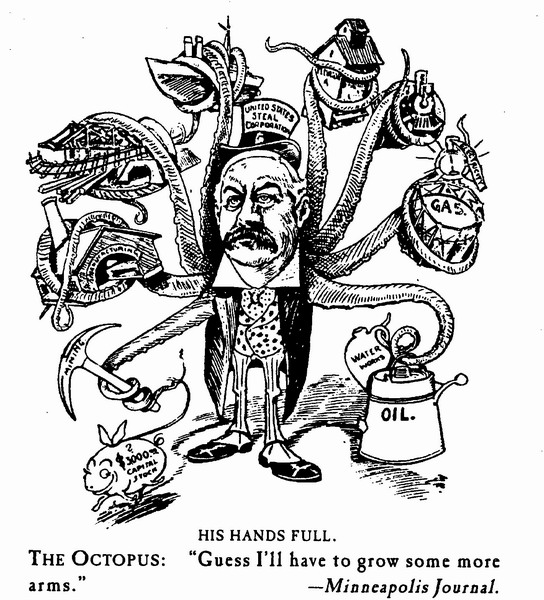

J. Pierpont Morgan: one of numerous political cartoons poking fun at the most powerful financier in the world, circa 1901

At the base of the edifice, deep below the earth, along the descending spiral staircase, was a network of catacombs that extended out like spokes of a wheel. Sixteen of them contained iron pipes which protruded from the central shaft to a distance of three hundred feet. The expense for these “terrestrial grippers” was notable, as Tesla had to design “special machines to push the pipes, one after the other” deep into the earth’s interior.21 Also in the well were four stone-lined tunnels, each of which gradually rose back to the surface. Large enough for a man to crawl through, they emerged like isolated, igloo-shaped brick ovens three hundred feet from the base of the tower.

Although the exact reason for the burrows has not been determined, their necessity was probably multifaceted. Tesla had increased the length of the aerial by over a hundred feet by extending the shaft into the earth. Simultaneously, he was able to more easily transmit energy through the ground with this arrangement. It is possible that he also planned to resonate the aquifer which was situated slightly below the bottom of the well. The insulated passageways which climbed back to the surface may have been safety valves, which would have allowed excess pressure to escape. They also provided an alternative way to access the base. Tesla may have planned to fill other shafts with salt water or liquid nitrogen to augment transmission. There may have also been other reasons for their construction.22

Just as the inventor prepared to test his new equipment, creditors began to encroach more vigorously and Tesla was never able to put the final fireproof protective outer facing on the cupola and tower. To Westinghouse he owed nearly $30,000,23 the phone company was billing him for the telephone poles and lines which they erected to connect him with civilization,24 and James Warden was suing for taxes owed on the land.25 With the exigency of time inexorably pressing down, the inventor worked furiously to link his transmitter to the power source and test its potentialities.

Throughout the early part of 1903 the engineer “performed many measurements of ground resistance and insulation resistance of the tower. He even considered temperature [increases] caused by ground losses, differences when salty water was spread around the base, weather conditions and time of day.”26

In the last week of July, just days before men came to cart away part of his equipment, the inventor fashioned a way to couple his behemoth and fire it up. As pressures reached their maximum with the cupola fully charged, a dull thunder rumbled from the site, alerting the hamlet that something was about to happen.

Strange Light at Tesla’s Tower

From the top of Mr. Tesla’s lattice work tower on the north shore of Long Island, there was a vivid display of light several nights last week. This phenomena [sic] provoked the curiosity of the few people who live near by, but the proprietor of the Wardencliffe [sic] plant declined to explain the spectacle when inquiries were addressed to him.27

Tesla’s mushroom-shaped citadel spewed forth a pyrotechnic eruption that could be gleaned not only by those who lived nearby but also by the populace inhabitating the shores of Connecticut, across Long Island Sound. But by the end of July the tower fell silent, never to raise its radio cry again.

It was a foggy morning when the Westinghouse crew appeared with their horse-drawn wagon and court order granting them permission to cart away the heavier equipment. The gargantuan edifice loomed as a specter of what could be, its head still obscured by the low-hanging clouds. Except for a guard, George Scherff, and a handyman, the entire crew was let go. His dream now hobbled, the sullen wizard crept back to the city to weep alone in his Waldorf suite.