36

THE CHILD OF HIS DREAMS (1907-1908)

I do not hesitate to state here for future reference and as a test of the accuracy of my scientific forecast that flying machines and ships propelled by electricity transmitted without wire will have ceased to be a wonder in ten years from now. I would say five were it not that there is such a thing as “inertia of human opinion” resisting revolutionary ideas.

NIKOLA TESLA, MAY 16, 19071

“It’s three o’clock in the morning, Mr. Tesla,” George Scherff rasped into the phone as his wife grumbled in her sleep.

“The sheriffs seized the land.”

“You owed Warden a hundred ninety-nine dollars!” Scherff said in amazement.

Fighting back a flood of tears, the inventor rasped, “I don’t have it.”

“I’ll take care of it, Mr. Tesla.”2

“Thank you,” Tesla said as his hand limply hung up the line. His hair disheveled, his clothes scattered about, the former man of the hour was going to have to let the maid in soon. What would she say about the drapes he had placed over the mirrors? And then there was the tower. He had to go back there to seal up the property. Would he have the strength to make the journey?

His appetite all but gone, Tesla hadn’t seen his friends for months. He managed a letter to Katharine as he rang room service to send up breakfast. “I’m ever in so much greater trouble,” he scratched out on his letterhead.3 But he would allow no one to truly know the hell he had entered. No sunlight must enter his room. He sat in the shadows and petted a wounded pigeon he had found floundering by the New York Public Library. If Boldt ever knew, the bird would have to be smuggled back out.

The withered man reached over to the envelope addressed to him in a feminine hand. Carefully he removed the letter and theater ticket. Marguerite Merrington had invited him to her new play Love Finds a Way. He stared at the title and broke down once again into uncontrollable sobs.4

Reconciling the torment, Tesla eased himself back into the social net as 1907 commenced. As part of his therapy, the recluse would surreptitiously board a moonlight train to Wardenclyffe. There, in the wizard’s chambers, the Balkan genie would hook up high-frequency apparatus to his skull and thereby impress macabre waves of soothing electrical energy through his brain. “I have passed [150,000 volts]…through my head,” Tesla told the New York Times, “and did not lose consciousness, but I invariably fell into a lethargic sleep some time after.”

In May, Tesla was inducted as a member of the New York Academy of Sciences.6 Slowly, he began to see once again that perhaps his grand plan could be resurrected. To raise the capital to keep his ship afloat, the inventor took out a series of mortgages, subdividing the enterprise into a string of hypothetical parcels. In the spring of 1904 he had borrowed $5,000 from Thomas G. Sherman, a law partner of Stanford White’s brother-in-law, and in the winter of 1906 he obtained $3,500 from Edmund Stallo, a son-in-law of one of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil partners; but those funds had long disappeared. Having dodged the Waldorf management for nearly three years, he took out another mortgage for an additional $5,000 against the rent he owed with the proprietor, George Boldt.7 And thus began a fresh plan for continuing to live in the lap of luxury without laying out another dime.

Boldt had done exceptionally well for himself. Having hobnobbed with the megarich for many years, the Waldorf manager had been able to take advantage of a number of inside opportunities. By 1907, a millionaire in his own right, he had expanded his base to become a banker, orchestrating the creation of the Lincoln Trust Company, which was located across the street from Madison Square Garden.8

Everyone except Tesla seemed to be flourishing. Morgan, through Jacob Schiff, had finally iced his deal with the Guggenheims to form the “Alaska Syndicate,” an enormous corporation which had been set up to exploit a copper find in the inviolable northern wilderness. Whereas the Guggenheim mountain in Utah contained only 2-3 percent ore, this lode, according to John Hays Hammond’s report, was 75 percent pure copper! A site of incalculable wealth, it would take a fleet of steamships, a thousandman crew, and an up-front capital investment of $25 million to construct a railroad just to reach the find.

But copper was not all the “Morganheims” had their eye on. They also began purchasing coal and iron reserves and hundreds of thousands of acres of forestland. “Thus the press, the few environmentalists active at the time, and a significant portion of the American people began to vigorously oppose the Guggenmorganization of Alaska.”9

With the growing need for copper wire came also a demand for insulation. Seizing the opportunity, Thomas Fortune Ryan and Bernard Baruch went to Europe to sign a contract with the king of Belgium (the former Prince Albert, an acquaintance of Tesla’s). Their plan was to take over the rubber industry in the African Congo. The financiers negotiated an even split, with the king allocating 25 percent for his country and retaining 25 percent for himself. As Baruch returned to Wall Street to handle marketing, Ryan traveled to Africa to oversee the product’s manufacture. Naturally, the tire companies were just as interested as the electrical concerns.

Once it was realized that Tesla’s plans to do away with transmission lines had been abolished, it seemed as if there began a feeding frenzy on copper stocks, as this market was now assured a continually increasing demand.

PANIC OF 1907

The first signs of economic distress was heralded in August, when John D. Rockefeller of Standard Oil was fined the staggering sum of $29 million for price gouging and illegal tariffs. Suddenly, Wall Street became edgy. In October, F. Augustus Heinze, a well-known speculator and enemy of the Guggenheim syndicate, began dumping large blocks of United Copper onto the market. Heinze miscalculated in his attempts to buy back the stock at a much lower price, and his shifty scheming resulted in a drop in the market and a run on his bank, the Mercantile Trust Company. Due to Heinze’s links to other financial institutions, the hysteria spread, and the Panic of 1907 began. Depositors emptied out every bank they could get into.

J. Pierpont Morgan called an emergency conference of all the bank and trust presidents, gathering them together in his newly constructed library in an all-night vigil. Sitting among his tapestries, original manuscripts, paintings, and jewels, the Wall Street monarch did his best to orchestrate a bailout of those institutions that were salvageable. Some, however, were beyond repair, and the stronger banks would go only so far in dipping into their reserves. Charles Barney, director of the Knickerbocker Trust Company, and father of “two awfully pretty sisters,” pleaded for assistance, but he was rebuked. Barney went home and put a pistol to his head. This act produced a wave of suicides, particularly among the Knickerbocker’s eighteen thousand depositors. With Henry Clay Frick acting as liaison, President Theodore Roosevelt would transfer $25 million into Morgan’s control. Although this figure matched the pledge of the stronger institutions, the new influx could only stretch so far. Boldt’s bank, the Lincoln Trust, along with the Knickerbocker, the Mercantile, and half a dozen others, had gone under by the end of the week.10 Now Tesla’s chances of resurrecting his own enterprise became even more remote.

“These are simply awful times,” Tesla told Scherff. “I cannot understand at all how Americans who are so daring and reckless in other respects can get scared to such a degree. My ship propulsion scheme is really great, and I feel sure that it will pull me out of the hole. Just how, I do not see as yet because it seems almost impossible to [amass] any money at all.”

“We’re still waiting to hear from the International Mercantile Marine Company,” Scherff said.

“Be patient, my man. They are certainly interested, but make conditions which I am unable to accept for the present. If I had just a little capital I would not worry about finishing my place.”

“What about Astor?”

“He told me over the phone, that he would see me as soon as possible, but up to present, nothing has materialized. I know now, that if I am to get capital, I can only get it from some fellow who has not less than a hundred million.”

“Then, Mr. Tesla, let’s hope for the best.”11

“Dulled by [his] own suffering,”12 Tesla began edging himself out of his depression by producing a number of acerbic essays for the electrical journals and local newspapers. Covering a wide range of topics, the inventor sought to vindicate himself and thereby try and make sense out of an absurdly ironic situation. Simultaneously, he sought to explain the Wardenclyffe vision yet again in the vain hope that some financier with a transcendent vision would come to his rescue. He was searching for a hero, not only for selfish desires but, in his eyes, for the future of the planet.

Under the guise of commenting on Commodore Perry’s exploration of the North Pole, Tesla explained in detail the modus operandi of his world wireless scheme.13 For Harvard Illustrated, he discussed Lowell’s Martian discoveries and the way to signal the nearby planet;” for the World and English Mechanic & World of Science, he described how a tidal wave could be created by using high explosives to set the entire earth in oscillation and discussed how this wall of water could be harnessed to “engulf” an advancing enemy;15 and for the New York Sun and New York Times he drafted a flurry of letters to the editor on such topics as his dirigible wireless torpedo,16 the transmission of voice by means of wireless, the “narcotic influence of certain periodic currents” when transmitted through the body for therapeutic reasons, the inefficiency of Marconi’s system, and the piracy of his oscillators by Marconi and another wireless inventor Valdemar Poulsen. Tesla also declared that the telephone was invented by Philip Reis before Bell and the incandescent lamp by King and J. W. Starr before Edison.17

Unlike Bell and Edison, Tesla wrote, “I had to cut the path myself, and my hands are still sore.” After reviewing his bitter battle for vindication as the true author of the AC polyphase system against such “feeble men” as Professor Ferraris, the wizard went on to discuss his seminal work in wireless telegraphy. “It will never be possible to transmit electrical energy economically through this [planet] and its environment except by essentially the same means and methods which I have discovered,” he declared, “and the system is so perfect now that it admits of but little improvement…Would you mind telling a reason why this advance should not stand worthily beside the discoveries of Copernicus?”18

This was a new Tesla—resentful, indignant, defiant, petulant. He was the discoverer of the AC polyphase system, the induction motor, fluorescent lights, mechanical and electrical oscillators, a novel steam propulsion system, wireless transmission of intelligence, light, and power, remote control, and interplanetary communication. He was an original discoverer, whereas Bell and Edison had merely modified the works of others. How dare the world deny him his due?

Tesla’s inventions were even at the heart of the new electric subway system which had just opened its doors beneath the thriving metropolis. Flooding, however, was a continual problem which marred this newest Tesla spin-off. The public had to be warned lest water cause corrosion of vital components, thereby increasing the risk of causing an explosion, and so another article advised the authorities on ways to cure the problem.

After one of his biweekly trips to his esteemed tonsorial artist for the warm compresses on his face and vigorous head massage to stimulate brain cells,19 Tesla picked up his walking cane and strolled out in his green suede high-tops to Forty-second Street, to the entranceway of the freshly tiled Interborough catacombs. He was looking for new office space. Descending the staircase, the creator was overtaken with a pompous sense of pride as he stood by the tracks to await the next train. It was an almost magical experience for him to drop down in one part of the city, only to pop up majestically in another spot a few minutes later.

While waiting at a stop one ordinary day in 1907, he was approached by a lad and asked if he were the great Nikola Tesla. Catching a gleam in the inquirer’s eye, the inventor answered in the affirmative.

“I have many questions to ask you,” the youngster said as Tesla moved forward to step aboard the train.

“Well, then, come on,” Tesla responded, unable to understand why the boy hesitated.

“I do not have enough money for the fare” was the embarrassed reply.

“Oh, is that all,” the electronic savant chuckled as he tossed the youngster the required sum. “What’s your name?”

“O’Neill, sir, Jack O’Neill. I’m applying for a job as a page for the New York Public Library.”

“Good. We can meet there and you can help me research the history of some patents I am investigating.”

O’Neill, who also had a keen interest in psychic phenomena, would go on a decade later to become a science reporter for the Long Island paper, the Nassau Daily Review Star. Eventually he took a position at the Herald Tribune, where he won the Pulitzer Prize before penning Prodigal Genius.20

In June came yet another legal suit, again from Warden, only this time from his heirs, as he had passed away. The amount was for $1,080, for money owed on an option Tesla had on four hundred acres adjacent to the two hundred he controlled.

“This is an old case which has been dragging in the courts for years,” Tesla told the Sun reporter. “I [had] intended to use this land for an agricultural experiment in fertilizing soil by means of electricity. I thought that by the use of certain electrical principles [in producing nitrogen], the soil could be increased very much, [and thus I had] agreed to take a certain option. But subsequently [I] discovered that the person who entered into the agreement had no right to make such a disposition…I told him the option was off…[but] the heirs of the owner had simply pressed the claim, and it is very likely that it will have to be paid.”21

VTOL’S: A HISTORY OF VERTICAL & TAKE-OFF LANDING AIRCRAFT

June 8, 1908

My dear Colonel,

I am now ready to take an order from you for a self-propelled flying machine, either of the lighter or heavier-than-air type.

Yours sincerely,

Nikola Tesla22

Astor was particularly interested in flying machines, but as would become his habit, Tesla would be working at cross-purposes. He wanted the good colonel to fund this work in aeronautics, but, in actuality, his ultimate goal was to earn enough money so that he could return to Long Island and reopen his world telegraphy plant. Thus, any potential profits were always threatened by the greater plan. This problem would continue to encumber any possible deal, especially with someone like Astor, who knew full well the inventor’s primary intentions.

One of Tesla’s most confounding prognostications came at the onset of 1908. Having finally located a new work space at 165 Broadway, Tesla felt that he was getting back on track. Shortly after he moved in, he received an invitation to speak at a Waldorf-Astoria dinner in honor of himself and Rear Adm. Charles Sigsbee. “Th[is] coming year will dispel [one]…error which has greatly retarded aerial navigation,” Tesla prophesied. “The aeronaut will soon satisfy himself that an aeroplane…is altogether too heavy to soar, and that such a machine, while it will have some use, can never fly as fast as a dirigible balloon…In strong contrast with these unnecessarily hazardous trials are the serious and dignified efforts of Count Zeppelin, who is building a real flying machine, safe and reliable, to carry a dozen men and provisions, and with a speed far in excess of those obtained with aeroplanes.”23

Assuming that the viscosity of the atmosphere exceeded that of water, Tesla had calculated that an airplane could never fly much faster than “an aqueous craft.” The inventor further reasoned that for highest velocities “the propeller is doomed.” Not only was its rotational speed restrictive, it was also subject to easy breakage. The prop plane, according to calculations, would have to be replaced by “a reactive jet.”24

In the short run, that is, for the next thirty years, the airship was the preferred method of passenger travel.

BERLIN, May 30 [1908]. Count Zeppelin, whose remarkable performances in his first airship brought such signal honors, today accomplished the most striking feat in his career so far. He guided his Zeppelin II, with two engineers and a crew of seven aboard, a distance of more than 400 miles, without landing…

All through the night the vessel…sped over Wertenberg and Bavaria, passing over sleeping countryside and villages and cities hardly less asleep…

It was announced and widely published…that the Count would come to Berlin and land at the…parade ground. In expectation of the event…the Emperor and Empress…and hundreds of thousands gathered there.25

It would be two decades before Lindbergh would capture the imagination of the public by flying solo in a propeller-driven airplane across the high seas, but airships were already close to accomplishing that feat. In 1911, Joseph Brucker formed the Transatlantic Airship Expedition, but he was beaten in the quest by the British air force, which succeeded in crossing the Atlantic eight years later.26 During World War I, the zeppelin ran frequent bombing missions from Berlin to London; Robert Underwood Johnson flew with fifty other passengers in a similar “leviathan” over Rome just two years later, in 1919.27 However, by the late 1920s this infamous legacy was all but forgotten, as these great airships were flying regularly across the Atlantic from Europe to both North and South America, and Germany was enjoying a reputation as the new leader in futuristic technology.

One curious and unfortunate footnote to history was the senseless choice to fill those blimps with hydrogen, a highly explosive gas, instead of nonflammable helium. Had engineers insisted on the much safer medium by heeding Tesla’s 1915 warning, the great Hindenburg disaster of 1937 would never have taken place, and the use of zeppelins would probably have continued for many more years to come. The problem stemmed all the way back to the late 1700s, when Jacques Charles, a French scientist, discovered that hydrogen was fourteen times lighter than air and filled a balloon with it. Monsieur Charles, like Count Zeppelin of Tesla’s time, gained great notoriety by traveling in his balloon fifteen or twenty miles at a stretch.

Today airships create stable platforms for TV sports cameras, advertisers use them because of their unique ability to generate “brand-name recognition,” and the military likes them because they offer singular advantages over the helicopter. They can be used for low-flying rescue missions without creating hazardous turbulence; they can be used to detect the submarine launching of cruise missiles by positioning themselves in a single area for hours or days on end; and they are extremely difficult to locate by ground surveillance. “Why don’t they show on radar?” a recent Popular Mechanics article asks. “Because the Skyship’s gondola is made of Kevlar, the envelope is of polyurethane fiber and it’s filled with helium.

They all have little or no radar register…The next-generation [air] ships would sip fuel. And they would stay operational for months at a time. As these are developed for military use, it is not too farfetched to predict that airships of the [21st century] may even be used for trans-Atlantic passenger service.”28

Tesla reveals in his Waldorf-Astoria speech his prophecy of the inevitable development of the jet plane, which would be about as close as he would come to explaining his highly novel and still obscure invention of an airplane that operated much like today’s VTOL “vectored thrust” aircraft. Tesla had played with a number of airship designs since his college days. One of his models, drawn up in 1894, was a traditionally shaped hot air balloon. Inspired by those he had seen at the World Fairs in Paris and Chicago, this dirigible received its continuing supply of heat from a gigantic induction coil that was placed high above the gondola, in the center of the hot-air container.29

The more recent model, which resembled a gigantic teardrop, took into consideration aerodynamic principles uncovered by such researchers as Leonardo da Vinci, Count von Zeppelin and Lawrence Hargrave, an Australian who, in 1890, fashioned rubber-band powered prop planes which traveled through the air over distances exceeding a hundred yards. This design was schematically prepared in the shape of a conventional airfoil by one of Tesla’s draftsmen in 1908.30

My airship will have neither gas bag, wings nor propellers…You might see it on the ground and you would never guess that it was a flying machine. Yet it will be able to move at will through the air in any direction with perfect safety, higher speeds than have yet been reached, regardless of weather and obvious “holes in the air” or downward currents. It will ascend in such currents if desired. It can remain absolutely stationary in the air even in a wind for a great length of time. Its lifting power will not depend on any such delicate devices as the bird has to employ, but upon positive mechanical action…[Stability will be achieved] through gyroscopic action of my engine…It is the child of my dreams, the product of years of intense and painful toil and research.31

Tesla’s vehicle had the “reactive jet” placed at its “leading edge,” or bulky end, and the fifty steering escape valves placed at the opposite, “trailing edge,” or tapered end. If fashioned as a lighter-than-air dirigible, the ship would have been modeled, in part, after the work of Henri Giffard, a Frenchman who invented the first dirigible in 1852, as well as Count von Zeppelin, the inventor who had been the first to construct a successful prototype with a rigid metal framework “within the bag.”32 Zeppelin was also one of the first to take into consideration wind resistance; his ships could travel at speeds of more than forty miles per hour.

A well-designed airfoil can develop “a lift force many times its drag. This allows the wing of an airplane to serve as a thrust amplifier…[If] the thrust is directed horizontally, a vertical lift force large enough to overcome the vehicle’s weight can be developed.”33

Thus, it appears that Tesla’s reactive-jet prototype could have also been fabricated in a heavier-than-air design. Oliver Chanute, M. Goupil, and O. Lilienthal were other Gay Nineties aeronauts whose patented works Tesla had studied. Naturally, he was also influenced by Samuel Langley and the Wright brothers, both of whom had produced heavier-than-air models that had actually flown.34

THE HOVERCRAFT

Another horseshoe crab-shaped VTOL designed by Tesla was called a hovercraft. This vehicle, which resembled a Corvette, placed the powerful turbine horizontally within its center. Operating much like a great fan, the engine created a heavy downdraft which caused the vehicle to rise up and ride along the ground on a layer of air.35 This invention, which apparently worked much like the hovercraft depicted in the original Star Wars film, was the early precursor of the army’s car-sized “aerial jeep,” which “derive[d] its thrust from ducted fans mounted rigidly in the airframe. To fly horizontally, the entire craft [was] tilted slightly [by the leaning motion of the driver].” In 1960, Scientific American could write that “this design is being explored because of its simplicity and…adaptability for flying at very low altitudes.”36

It is doubtful that Tesla ever constructed any of the heavier-than-air hovercrafts, although he may have built a hydrofoil model to skim over the Hudson. There is no doubt that he also constructed “lighter-than-air” vessels which could be operated by means of remote control.

Ideas inherent in Tesla’s hovercraft and paramecium-shaped reactive-jet dirigibles evolved into today’s Harrier fighter plane, a supersonic aircraft considered one of the military’s “most potent fighting machines,” and the new, yet-to-be-built Lockheed Martin X-33, which is a lightweight VTOL replacement of the space shuttle having a new experimental engine, the plane itself being shaped like a “flat-flying wing.”37

The seeds of this technology can also be traced to the work of “A. F. Zahm, a prominent aeronautical engineer who patented [in 1921] an airplane with a wing that would deflect the propeller slipstream to provide lift for hovering.” Although Zahm did not actually construct his plane, his concept, which may have been influenced by Tesla’s work, evolved into the English Hawker, a British fighter developed in the 1960s. This airplane utilized nozzles to deflect a slipstream downward for vertical takeoff or for hovering and horizontally for normal flight. Utilizing “thrust vectoring,” this apparatus became more workable with the development of the Pegasus engine, an extremely powerful turbojet found in the Harrier, which was unyeiled in 1969.38 “From the pilot’s point of view, there is only one extra control in the cockpit: a single [lever] to select the nozzle angle.”39 “AV-8B Harrier: The U.S. Marines’ ground-support jet can take off vertically, hover close to a battlefield and let loose missiles, cluster bombs or smart bombs.”40

FLYING ON A BEAM OF ENERGY

Whether or not Tesla was able to perfect his design for aircraft that operated without any fuel—by deriving energy from wireless transmitters—is unknown. This concept, however, has been adopted by the military. In 1987, the New York Times and also Newsweek reported large glider planes “powered without fuel.” Their energy is derived from microwaves beamed up from ground transmitters to large, flat panels of “rectennae” on each wing’s underbelly. These “special antennas, laced with tiny rectifiers that turn alternating current into direct current, power an electric motor to run the craft’s propeller.”41 This concept is also utilized as solar panels onboard spacecraft as well as on solar-powered automobiles.

The Flivver Plane

Tesla Designs Weird Craft to Fly Up, Down, Sideways

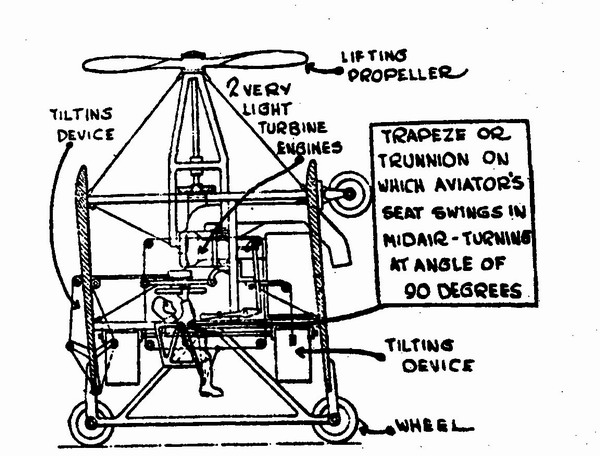

Craft Combines Qualities of Helicopter & PlaneDetailed descriptions were available yesterday of the helicopter airplane, the latest creation of Nikola Tesla, inventor, electrical wizard, experimenter and dreamer.

It is a tiny combination plane, which, its inventor asserts, will rise and descend vertically and fly horizontally at great speed, much faster than the speed of the planes of today. But despite the feats which he credits to his invention, Tesla says it will sell for something less than $1000.12

Although this article was written in 1928, Tesla first applied for patents on his new “method of aerial transportation” in 1921.43 Nevertheless, designs for propeller-driven VTOL aircraft dated back even before the turn of the century. One of Tesla’s earliest and most primitive helicopters looked much like a washbasin, with vertical shaft rising from its center. Flailing out, like the skeletons of two umbrellas stacked above one another, were its dual horizontal propellers. This vehicle evolved into the flivver plane, which took off vertically like a helicopter and then flew like a normal airplane, when the propeller and craft were rotated 90 degrees into the horizontal position. The concepts found in Tesla’s flivver plane can be found in another advanced military VTOL aircraft called the V-22 Osprey. In this design, the body of the vehicle resembles a normal military transport plane. It is the propellers, at the ends of each wing, which rotate ninety degrees from the helicopter position, for vertical takeoff, into the normal airplane position for forward flight. Used in the recent war with Iraq (February 1990), this vehicle, like the aerial jeep and VTOL Harrier fighter jet, evolved directly out of Tesla’s designs. As Tesla’s work in aeronautics has never received much publicity, it is quite possible that the military adopted it in secret.

VTOLs can be grouped into four general categories. The aircraft could be tilted, the thrust could be deflected, the propeller or turbojet engine could be tilted, or a dual propulsion system could be utilized. Bell Labs began constructing propeller-driven VTOLs in the 1940s. Early models included the wing-tilted XC-142A, developed by Vought, Hiller & Ryan, and the X-19 propeller tilted craft, developed by Curtiss & Wright.

The New Weapons

Every service has its favorite new weapon, and the Marine Corp’s favorite is the V-22 Osprey, an aircraft that can take off like a helicopter and fly like a plane. Just the craft to ferry Marines quickly and far into the desert, argue its manufacturers, Bell Helicopter Textron Inc. and Boeing Vertol Co…[The vehicle can carry] 24 men and costs $40 million.44

Tesla’s invention of the helicopter-airplane, which he called the flivver plane. (New York American, February 23, 1928)