While in California I received a call from a close friend of my mother’s asking me to come to Dallas at once, and I did. My mother had apparently been felled by a stroke and was taken into a care facility. When I got there, she was in bed and appeared unwell. I tried to comfort her and cheer her up, but we could not communicate too well verbally. I hung one of her favorite pictures on the wall of her room, the small oil painting by Georgia O’Keeffe titled Taos, New Mexico that she had purchased not long before. She smiled when she saw it, and there was a familiar contact between us through the art. There was an appreciation we shared, of the painting and each other.

She died peacefully in her sleep two days later. While I was at dinner that night I got the call that she had stopped breathing, and by the time I returned to the facility, she was gone.

I was sad to lose her. I was stoic to a degree, through the funeral and the good wishes and kind concerns of her friends and mine, the gifts of food and the gatherings, but there was a time after all of it when I was standing alone in her house and began to cry uncontrollably for a time longer than I could count or can remember. It was High Lonesome in its most acute, severe form. Every pore wept, every beat of my heart hurt, every breath I took was cold. I missed her presence, naturally, but more than anything I felt left behind, left out, and lost. It was selfish of me but I felt I was friendless at that moment, that she and I had encountered a barrier on our journey that I could not see past as she ran through. I did not despair for her well-being; I held a certainty of her individual continuity and life. I had the unshakable sense that she was fine where she was. The feeling of loss went deeper than all of that. For a time I was inconsolable, but I did not let it show. I missed her.

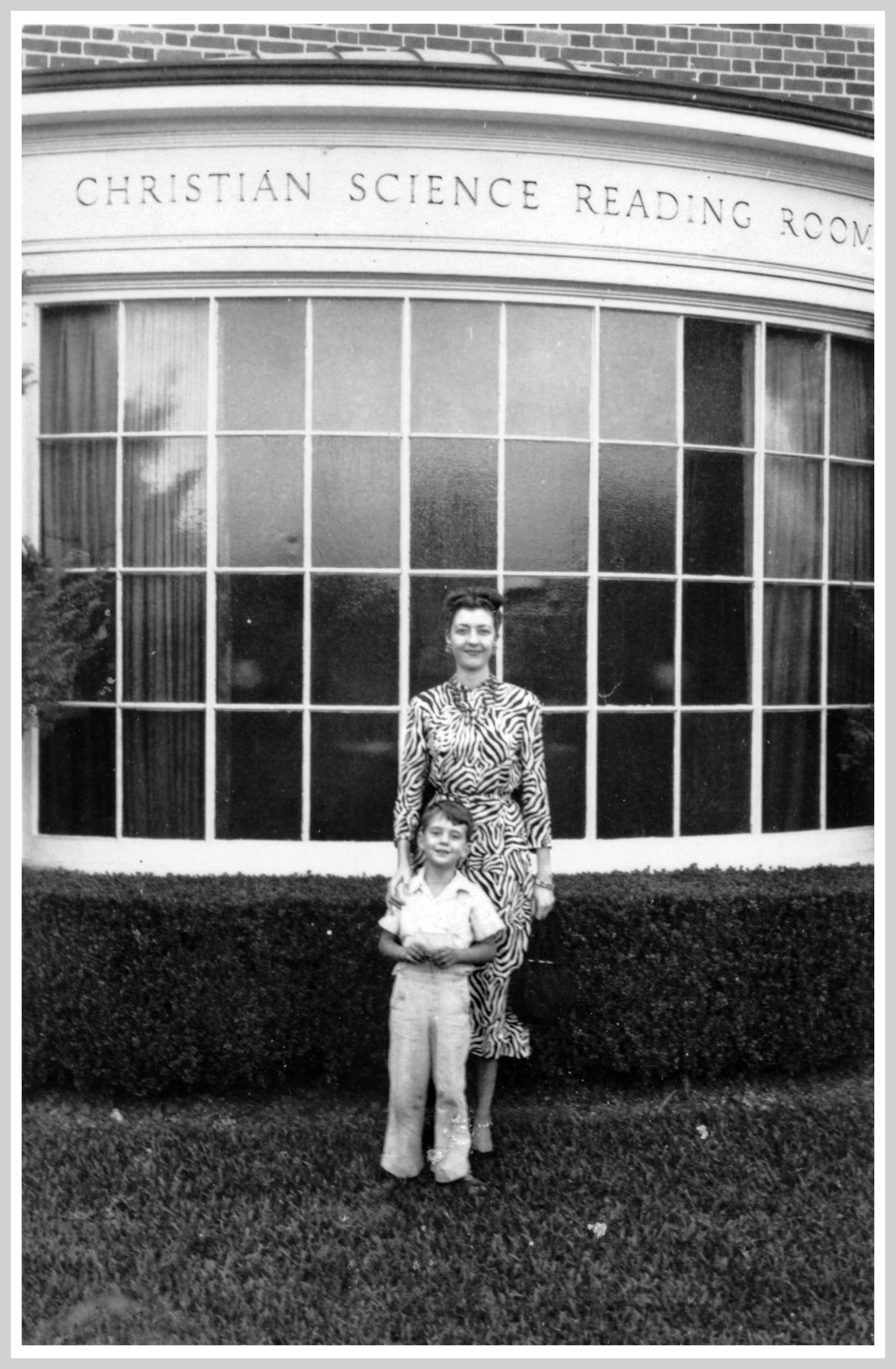

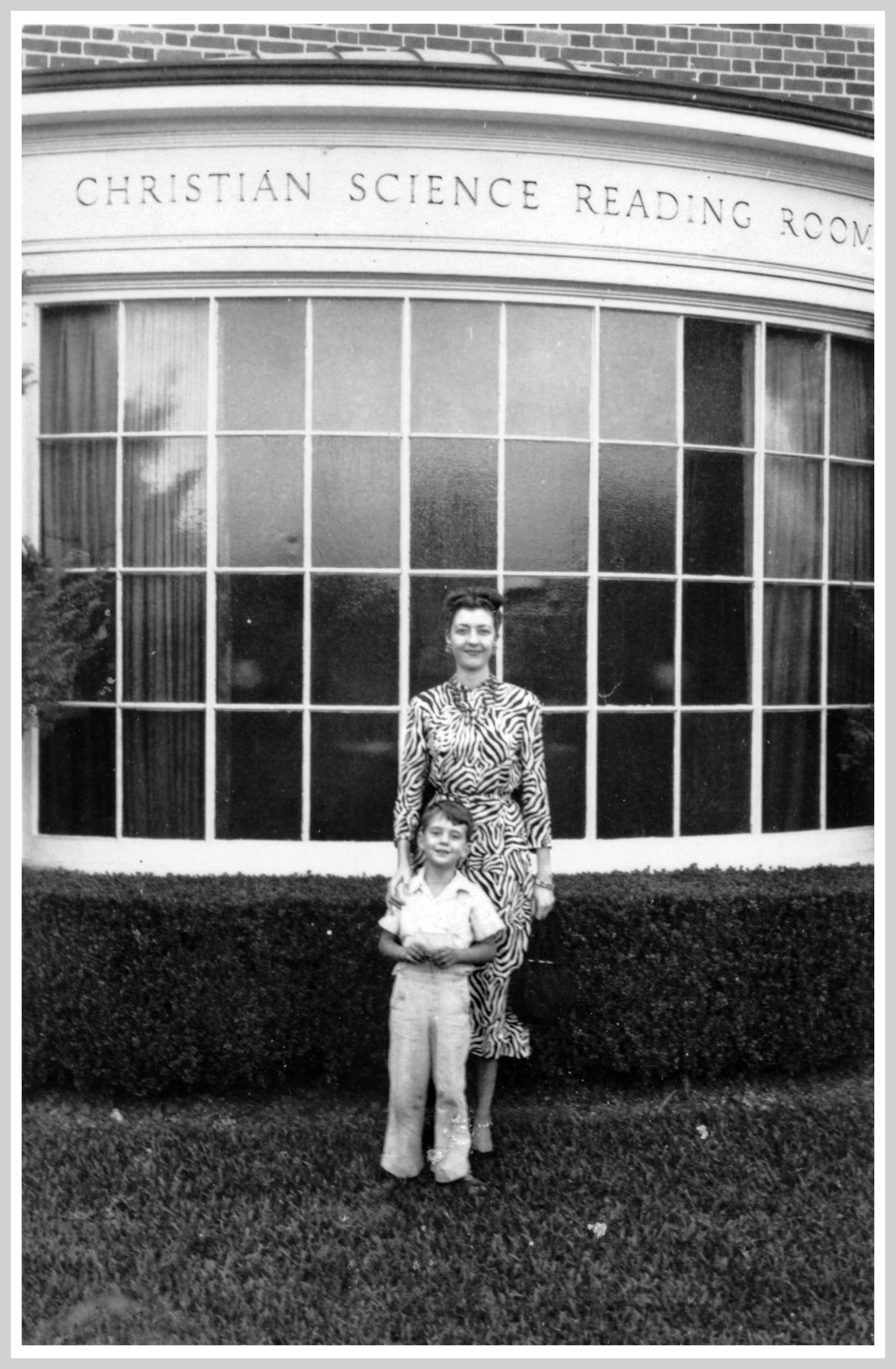

Mother and I had talked daily, almost never about anything other than things spiritual. This was a pattern from since I was as young as I can remember. Bette was not glib or particularly quick or funny, but she was a deep thinker and could be very loving. So the conversations concerned how we each were dealing with what mortal life was dealing us.

Some years earlier my mother had said to me that she wanted to give all her money away, to get down to owning essentially nothing and live an ascetic life. I admired her for this and told her so, but the goal seemed an impossibility to me. Too much water had passed under the material bridge. Nevertheless, I understood her desire and her motivation. The money was a mark of success, but it had become a burden to her, and not all that easy to give away. She felt it slow her and divert her from the spiritual sense of life, the truth she had practiced and loved.

She was also depressed, as she had become estranged from the board of the Liquid Paper Corporation. The men she hired to run the company had joined with her ex-husband to push her out. There was much acrimony and many harsh words. It was devastating to her. She had settled into an awful, destructive kind of warfare over property and control. The board devised a solution: the company should accept an offer and be sold to Gillette before the rancor among the management destroyed the business. She reluctantly agreed to this, but only under the condition that after the sale, all the executives she had hired would quit. I never understood her logic in this, if there was any, but I had a suspicion that revenge or some kind of punishment may have been active in her mind, as well as a great sorrow. Whatever it was, I have no doubt that it killed her.

Even though I didn’t know exactly why my mother had wanted to give her money away, I suspected the reasons. Hers was not sudden wealth, but it was great enough to get her name in the papers and to put her life under scrutiny. As I saw it, wealth and success were not married in her mind the way they are married in the mind of a lottery winner or someone who strikes oil. For her it was a gate slowly opening on materialism, letting it loose on her lawn. It had even taken some shallow root.

She bought ermines and jewels. She built a large and in my opinion beautiful home, and she lived with servants and cooks and the attendants of her business. She bought a Rolls-Royce. Actually, I bought the Rolls-Royce on her behalf, at her direction. I think it may have created one of the unhappiest episodes in her life.

She had trouble buying cars because she had no tolerance for car salesmen, an obvious generalization she refused to correct, and wanted nothing to do with them. So the few cars she bought got older and broke down. When I returned from London the first time, I told my mother about John Lennon’s huge Rolls Phantom V that had picked Phyllis and me up, and suggested that she buy a Rolls; then she would never have to buy another car. It would last forever, or so I foolishly thought.

She combed through magazines and finally picked out one Rolls-Royce whose shape she liked. It was a 1963. This was in the early 1970s. When I pointed out that it was a used car she responded that I had said it would last forever, so what difference did it make? She didn’t like the way the new ones looked, thought they were overpriced, and she very much liked the way this model looked. She had a point. I offered to shop for one for her.

After a little searching I found a prime example in LA that was white and recently restored. She thought it was beautiful, bought it, and brought it back to Texas.

She had flaming red hair that she began to dye redder and redder as she matured and her hair turned grayer. At one point I asked if she knew the natural color of her hair and she said no, she thought it was all gray, but if she could have her hair any color she decided she liked orange. In her white Rolls and orange hair, she and her second husband made the society rounds of Dallas.

One late evening after the symphony, she and her husband and another couple were driving home along the empty Dallas tollway when the car died and rolled to a stop on the side of the road. It was late and they were a perfect mark for the car full of thieves that rolled up behind them and, with drawn guns, approached the four in the car and demanded money. My mother was draped in hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of jewels, and they took all of them except her bracelet. As she told the story, when one of the men demanded the bracelet, she had been unable to open the latch and could not get it off her wrist. She told the robber she couldn’t get it off and he said, “I guess I’ll just have to shoot it off there, then,” to which, she said, she calmly replied, “Oh, please don’t do that.” The robber thought better of it and left.

I can only understate the trauma the incident caused her and the deep soul-searching that ensued. The great display of wealth attenuated quickly after that. She sold the old giant white Rolls and bought a new small one in a subdued metallic beige. She stopped wearing the furs. In her mind, both were big steps out of the trappings of wealth, as they are so properly called.

We discussed on many occasions the slow degradation of the quality of her life as the wealth increased; we talked of the shadows that lay long across the pool in her backyard and obscured the spiritual values she cherished, and of her real reasons for living, which were unconditionally directed toward finding God. To her, wealth was not evil per se, nor was money undesirable, but she struggled intensely within the constraints of financial freedom and the weight of expensive material objects. She may have fallen into a tub of butter, but she never lost sight of her unending search for truth. Truth with a capital T.

Her efforts to assimilate the wealth made me recall the second time I went to see and stay with John Lennon. While we were sitting at his piano, he asked if I wanted to see his car. It was an odd question, I thought, but I said, “Of course.” I remembered the long liquid-shiny solid-black Phantom V that had picked Phyllis and me up at the Grosvenor House that day, and how there was a moment when the enormous car’s errand—picking up the somewhat scraggly only-two-of-us—seemed incongruous and strangely out of place. The car was nearly new and almost twenty feet long, a symbol of status, state, power, and money. In the context of the rock and roll counterculture it seemed an anomaly.

We walked out to his garage on that particular evening, and when he opened the door and I saw it, it made a kind of perfect sense. He had painted the big black car bright clown-yellow and covered it with hand-painted multicolored psychedelic images in panels and scrolls that made it look like a huge circus wagon. Years later it sold for millions as an objet d’art. The way it was painted became more valuable than the car itself. As far as I knew, he did not drive around in that car to any great extent, and finally parked it in his garage, where it sat for private display as sculpture.

My mother had a similar problem of assimilating her wealth, but without the attendant celebrity. While she was alive, in what looked to me like a sincere first effort to disperse the money she had made from the sale, to in fact “give all her money away,” she started a couple of foundations—the Bette Clair McMurray Foundation and the Gihon Foundation—and began transferring her estate a little at a time into them. But by the time she died, she still had a sizable personal fortune. The foundations did not have the same joie de vivre that Lennon’s circus car did, but they were on the same train of thought. Great wealth from a sincere effort, arts, humanity, or good business creates a conundrum. The wealth is not the object of the success at hand, but such wealth is perceived by many as an end in itself, as a reason for living. This did not seem to be so for Lennon, and I knew for a fact it was not for my mother. The two, however, solved the problems in their own way, and the foundations were a good fit for my mother’s individual goal, as turning the Rolls into a circus wagon was for Lennon.

The sale of the Liquid Paper Corporation had been consummated only about a year before my mother’s passing, so the corpus of her estate was quite large. After the IRS settled up with her estate, there was enough to be a generous inheritance for me, but very much smaller than the press—and everyone I knew—imagined. Still, an inheritance of this size for someone like me, raised as I’d been raised, and living as I had been, was like a cross between a tsunami and a Category 5 hurricane but with winds over two hundred miles per hour. It was the most curious mixture of total destruction and a new expensive broom that swept clean the mess and replaced things as it went along.

Money cannot really be controlled, because in essence it is ephemeral, spiritual, and constantly in motion, moving back and forth between perceived states of frozen and liquid. In one time frame it is stagnant and in another it is like a typhoon. It can be ridden for a moment but it will run where it will, almost as if it has a mind of its own, which it clearly does not. Its actions are more of a mystery than a science, as most economists will testify. The only thing that is made with money is more money. The idea that one can somehow set up a wind farm in a windstorm is an ignorant one, revealing a lack of awareness of the forces at work.

After my mother passed, it was a bad time in general for me. I didn’t have much of an idea what I was going to do with my life, much less with the foundations she had started or the remainder of her estate. It felt disrespectful to think of money at this time, but it was an enormous and increasing presence and it seeped in, like wind through a cracked window. I began receiving calls from people who offered congratulations as well as condolences. I didn’t know what to say, so I said thank you to both.

Weirdly, amid the deep sorrow, I was also confusingly comforted. Now that I had the money to do some things I was truly yearning to do, I began to think of what else I might do. I began to think of money as causal—I felt that whatever I could think up, the money would facilitate and even create. I made no effort to argue against this notion, since I didn’t know any better at the time. I was happy to have a new art form, embodied in “Rio,” to introduce to the public and was motivated to pursue the culture that I was sure would follow it. I knew that Bill Dear wanted to direct a movie, and now I had enough that I could also unilaterally produce a movie that he could direct. All of these things had been possibilities before, but now they were becoming realities. Now that I had the money.

This time, I thought, Bill and I could write together and produce a real movie, with a director of photography and a line producer and real movie actors. I could see to it that Bill had whatever he needed, and we could make a movie that was designed to simply and directly sell popcorn—a fun movie, a comedy of sorts, at least a few jokes, with a tad of action and a simple narrative.

We could do it cheap, as features go. “Rio” notwithstanding, we had pulled together Elephant Parts for a low price and made it look expensive. We used low-cost camera tricks and got help from our friends. Now that I had the money, I could produce a real Hollywood movie and send it around the world.

Bill would have his chance to direct a feature and move into the society of other filmmakers, to meet heroes of his like Steven Spielberg and Sam Raimi, possibly even work with them. I thought it was a way to offer my gratitude for the help he had been with “Rio” and Elephant Parts. And while I knew nothing of the movie business as such, I could learn it quickly. I had been successful, in a way, with these other efforts, and now I had the good fortune of an inheritance to make a low-budget movie feasible, and keep it completely under my control. I could let Bill do what he wanted, pretty much.

And so it happened that—within weeks of my mother’s passing, as the tears stopped, leaving me silent in my contemplations of the next steps in my life—without even the slightest indication of a costume change, money began a masquerade and donned the appearance of being able to make things happen, to stop sorrow, to create worlds of imagination, to create friends. Money was an ever-present, unending wind in the sails of my little boat, and it would create, build, and establish wonders. In those few seconds, filled with thoughts of the good work I could do, I became a Hamburger Movie Tycoon.

The wind that brought my main thought—I can make this happen—through the door also closed the door behind it and locked it. Whatever lessons my mother had learned from her wealth she carried with her to her grave as I fell into the same tub of butter.

Days after my mother died, I met with the board of the foundations she had set up, which consisted of the two women who had helped her organize them, Patricia Hill and Maryanne Henneberger, and me. Each foundation was focused in a different area, with the McMurray Foundation making grants to assist women generally and women in business specifically, and the Gihon Foundation focused on operating a program supporting the arts. I asked Patricia and Maryanne if they wanted to continue the foundations or just close them and disperse the funds. They both said they would be happy to continue if I wanted to, so we came to the decision to keep them going as long as we could, given that the funding given by my mother would now slowly decrease over time.

With that decided, we kept making grants along the lines my mother had started. I thought for a brief while about continuing to fund the foundations from the inheritance that came to me, but since they had already been funded, I thought I would stay the course with building my production company, Pacific Arts, with the idea that at some point I could possibly fund the foundations as she had: with profits from a successful enterprise.

Fortunately for me, my mother had left the estate in good shape and under the wise executorship of competent men. The beneficiaries were clearly identified and there were no conflicts or contests. She was very generous to all her family and loved ones. Unfortunately, my business was held together with tape, and it would take more than a windfall of money to make it stable and secure.

It didn’t seem to make any difference how hard I worked at it. I couldn’t get the business to grow any legs to support itself or nourish a band of execs and administrators. So far nothing I was doing was making money. I had put the money my mother had given me before her death into Pacific Arts, and it had scrimped along. Then, when the inheritance landed, I was able to consider doing more projects, expanding its expenses without any real idea of how to expand its income.

The distressing part is that I had no clue what was wrong or how to fix it, and this ignorance was now being sustained. I had money to throw blindly at a problem that was not only hidden but systemic.

The problem was, of course, that I had started to depend on the causality of money and had stopped trying to form a band. Had I stayed with the band dynamic, I might have seen that it made no difference how much I could pay a musician; if there wasn’t a band sensibility, the player would only do the job and move on to the next gig. No creative return would develop, and certainly no loyalty. The key element of a band is the sense of family created when it plays together, so that when the music is made, everyone rides the joy. It is not called “playing” for no reason.

At the time, music videos, the main output of my current band, had very few places to play, but we were only a few years away from the migration of the Internet from its military roots into the general culture; Vint Cerf and Robert Kahn were writing the protocols—TCP/IP—that would make the distributed network available to everyone. All that would be needed was a personal computer, like the one Woz and Jobs put together in their garage in Los Altos in 1976.

And while the band that had recently formed in my life had produced another artifact, Elephant Parts, that was starting to gather a little steam, the idea of home video was just starting up, and there was no real distribution system in place. The studios were eyeing video as an ancillary source of income for their movies, but Elephant Parts wasn’t a movie. Videotape was virtually unknown, and the presence of video players in homes had only started to build.

The best idea I could fashion for developing a market and selling Elephant Parts was to move Pacific Arts to LA, where perhaps I could attract some executives to help me, and could try to expand my distribution business by buying or licensing other products and producing more of my own. I could do that because I had the money and could support the move. But it was a move in the wrong direction.

I had the money to move anywhere, yes, but the self-importance that came with the money hid from me the real parties and fun the cyberculture was having, the technology bands that were playing and the garages they were playing in. All around me, literally down every block in every garage, Silicon Valley was coming alive with band after band after band, starting companies that would eventually become the large-scale leaders of the world. The new cyberculture, the new creative centers, the new garage gardens and indoor plants—the seeds of all these had been sowed in the seventies, and they were now sending up shoots and young blossoms to the north, up the Northwest Corridor, toward Seattle. The cyberculture was following the counterculture up the coast, led by Stewart Brand, the Grateful Dead, Ken Kesey, LSD, and a whole new young world of Merry Pranksters.

I took LSD a few times in the 1970s, enough to get a pretty good feel for the drug and to open myself up to it enough to enjoy it. I got my first hit from Owsley, the famous acid maker from LA, since he was the main distributor for a while, and then I got a few doses from a friend who always had it lab-tested for purity since he was afraid of getting a bad dose. I never had a bad trip; there were ups and downs, but for me the ups far outweighed the downs. There was very little known about the drug at the time, but once I took it I could see how different life looked. This view was very far from alcohol-, tobacco-, and cocaine-induced perspectives, those produced by the big-money drugs. My trips with LSD were as pleasant as the lore around them promised, with doors opening as expected. Then I took it a few times more, as a sacrament to see if there was higher light than dancing in only one corner of the universe. The last couple of trips carried a message that was part of the trip itself—the message was “You don’t need drugs to reach this space, and you will come to a point where you will not take them anymore but still reach the same state of mind.”

Once, several years before I took class instruction with Paul Seeley, while very high on acid, I opened the Christian Science textbook Science and Health and started reading it just to see how it fit in this mental landscape. I was astounded to see how the same frame of mind I was in at the time was present in the writings. I read Science and Health for hours straight, continuously amazed to be reading something that conveyed the same clarity and powerful insight I was experiencing. I finally stopped all drugs once I met Seeley, but I was fascinated by the way the ideas and reality I was taught in class were as familiar, as high, and at least as profound as any of the ideas and the reality that acid had showed me.

Through the 1960s and ’70s there developed a certain class of thinker, made up of those who looked closely at all aspects of culture and society from the very different viewpoints that acid and cannabis brought in. I was good friends with these people, and won’t put their names here, but they were close enough to talk to and insightful enough to discuss the drugs. I was essentially on the sidelines of these new thoughts and ideas, but close enough to witness them and understand where they were coming from. Even then, I had only a slight idea of the effect the whole counterculture was having on the developing cyberculture.

Wozniak and Jobs had created the first Apple computer in 1976, the same year I went through class instruction. I have no way of knowing whether they were high or not, but I was not surprised when Kary Mullis said he had been high on LSD when he had the inspiration for inventing the polymerase chain reaction method. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for this outstanding, beneficial work in 1993. Since then I have learned from research that Francis Crick said he was high on psychedelics when he thought of the double helix, and there were other examples like this. I assume that some of this information is suspect, especially given the way rumors float around and among bands, but I also assume that some of it is true.

From my personal experience I can understand how the psychedelics—or entheogens, as they are now called—could have stimulated some very powerful new ways of looking at things and bringing hidden analogies to light. The more I looked into the new high-tech world, the more surprised I was at the similarities between that world and the counterculture of the times. The fragrant gardens and groves to the north seemed indistinct, almost like Elysian playgrounds, removed from business. The idea that this would become the financial and intellectual capital of the world was only a faint gleam of sunlight on fresh-growing fields. Unfortunately, it was too faint for me to see at the time.

The shiny object that drew me in was Southern California and Los Angeles, the center of media distribution. I thought this distribution center might work for new media as well. As the base of installed video players in homes grew, I assumed that home viewing would be a good business to develop, as well as a good sales base for original productions. So I decided to set up a distribution company in Los Angeles and produce movies and videos that I could sell through it. My first full-length movie would be The Adventure of Lyle Swann, the movie Bill Dear and I were writing.

I also started buying and licensing documentaries—or “nontheatrical titles,” as they were known—for the catalog. I licensed the entire series of Jacques Cousteau documentaries on the ocean and sea life. I licensed an Agatha Christie series. I licensed foreign films like The Official Story. I was surprised they were available to license, but I shouldn’t have been, since the thinking at the time, aside from general ignorance of the burgeoning home-video business, was that once a show had been on television and played a few times, its value had depreciated to nothing. All the producers of these documentaries were delighted that I was interested in licensing these “leftover” rights and that there was yet another market developing for them.

I licensed or bought everything I could, and as it turned out, I acquired them a few years before I could sell them as videotapes. I was still years ahead of the market, and for some inexplicable reason I had no sense that I wouldn’t be able to sell them immediately after getting the rights. I was certain that people would want to program their own television sets to suit their own schedules, choosing what to watch and when. The bottom line was that in just a few years I had purchased the rights to what was now the largest nontheatrical video catalog in the world, but sales were slow, to put it mildly. I was finally able to recover some of the cost—but in a way I never imagined.

Though they stem from the same root, Celebrity Psychosis and the Hollywood Mind are quite different. CP is fully delusional. The bearers justify their actions through the perceived amount of their fame. The recognition and the fame validate and confer power and authority, specifically the authority to give opinions on subjects about which the Celebrity Psychotic knows basically nothing.

The Hollywood Mind, on the other hand, is not delusional but is instead based on the actual value of public acceptance, specifically in the form of retail sales. In the Hollywood Mind, little thought is given to aesthetic principle or how spiritual and artistic value is created and measured; it curates art based strictly on the broadness of its appeal and its commercial value. Income in the form of money is the metric of the Hollywood Mind, whereas power is the metric of Celebrity Psychosis.

The Hollywood Mind, despite the name, does not exist only in Hollywood, although Hollywood is the largest collection of Hollywood Minds in the world and, as such, is the Galápagos Islands for studying the evolution of the phenotype. But the Hollywood Mind can be found in many places and many industries. That the business of Hollywood is underpinned by the arts makes the HM thrive there, since the arts are considered only a matter of opinion until they make money.

By the time my mother’s estate was settled, I began—for what reason I can’t say—to recognize Celebrity Psychosis when it would appear, and it began to fray and fall away in bits and pieces, disassembling like a vampire in sunlight. Recognition became meaningless and obscurity appealing, but the crumbling, corroded infrastructure of CP remained intact just enough to cause confusion. The inheritance had replaced the window dressing of CP with the mentality of a Hamburger Movie Tycoon, and the logic of the Hollywood Mind lingered as well, having crept in and set up a rationale for the new Pacific Arts offices in LA.

Bill and I hammered out a script for The Adventure of Lyle Swann in my and Kathryn’s home in Carmel, and once we had something shootable, I thought it would be a good idea to leave Bill to his own devices, directing as he wished, free from any influence by me. We hired Harry Gittes as the producer for the film, and Kathryn and I took off for a vacation in Greece.

It wasn’t as class-A crazy as leaving the country in which I had a hit record starting up, as I did with “Joanne” in 1970, but it was close. If anything requires hands-on management and care of cash flow, it is shooting a movie. The motive to let Bill and Harry have their way was a good one as far as the humanity of it, but the result was not as good as the motive. Bill deserved a chance. I could provide that, and I didn’t want to muck with this project as much as I had with Elephant Parts. Leaving the project in the hands of Bill and Harry was not a bad idea, but it wasn’t as good an idea as staying.

By then, Elephant Parts had won a Grammy. I had been delighted with the critical reception it received and was just as happy to learn it had been nominated for Video of the Year in 1981. The National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences had never bestowed such an award before, and they only awarded one more, the next year, to Olivia Newton-John, so my Grammy turned out to be a rare Grammy. It may have been that after the award, NARAS officials thought the music video was a passing fad. The video was so far outside their usual channels of production and distribution that no one knew what to do with it, only that it had shown up on the scene and gained all sorts of attention from and influence within a large group of viewers, most of whom were kids. As it worked out, shortly after the Grammy for Video of the Year was discontinued, the MTV Awards took it up, leaving NARAS behind.

Orphan though it may be, I now treasure the award, even though I didn’t know how to take it at the time. The mixed feelings may have come from the incipient notion that such awards are the spoils of hard-fought competitions. I did not like the idea of artists pitted against each other, since the essence of artistry includes diversity, individuality, family and friends, all the direct opposites of competitive efforts for the same ultimate position.

When Elephant Parts won, I was wildly excited in spite of myself. I accepted the award without a word of thanks to Kathryn or Bill from the podium. In fact, I left off all mention of the production team and made a joke instead. The joke was this: after I walked to the podium and accepted the award, I said, “Thanks very much, and now that I have this national exposure, I’d like to take the opportunity to let everyone know I have one chrome wheel for a 1963 Camaro that I would like to sell.” I meant it to be a Tuesday absurdity—something one lonely hippo might say to the other. Instead it came off as insensitive, weird, and eccentric, and was met with soundless stares. I was embarrassed.

Additionally, the acceptance speech received no actual “national exposure,” since it was not televised. The award was given during the preshow ceremonies, where they honor arcane technologies and practices, like the award for the best instrument created with yarn strung across an old fence.

While I was in Greece, Harry and Bill shot The Adventure of Lyle Swann. I returned eager to help, if I could, in getting Lyle Swann ready for distribution in theaters and Elephant Parts distributed on home video. With almost amazing precision and perfect aim, I once more started shooting off my own feet, one toe at a time.

I had bought a billboard on Sunset for Elephant Parts and put on two large-scale publicity events, one each in New York and LA. The expenses piled up as fast as any public interest did, and at what I assumed was the height of public awareness, the pinnacle of the marketing effort, I said to my tiny staff, “Now! Now, is the time to really push and sell Elephant Parts! Now that we have their attention!” In a live twist of an old joke, they all asked, “Whose attention do we have?” For all the accolades Elephant Parts received, there were still no buyers in the still very niche home-video nonmarket. Other than its funny name, no one had any idea what it actually was.

The band of Bill Dear, Bill Martin, Kathryn, and me finally came apart, and although we were all more or less civil to each other, a great silence had come over me and Bill Dear, and things were particularly troubling at home between Kathryn and me. Kathryn refused to join me in LA and insisted on staying in Carmel. She said Los Angeles gave her a headache. I couldn’t blame her for this, but I was lonely in LA and things were getting more and more difficult and distorted there all the time.

Without each other to console and counsel, Kathryn and I both began to sink under the weight of the distance and, to a great degree, the new money. It is very hard to describe just how this happens, especially since many people seem to carry around an idea that money confers a kind of social and financial security. Thanks to my mother, I started to learn something different, but she was gone too soon to advise me, leaving no further instructions.

I have talked to friends who have become Masters of the Universe and made billions of dollars, and they all have the same two concerns in common. The first is that they feel as if, in some unexplainable way, their wealth and success is a fluke, like hitting the lottery. Second, they fear it will all suddenly vanish and leave them wretched and homeless, living under a freeway overpass.

Add to this general malady of supermoney the specific quirk of windfall wealth and you get some idea of the pressures that build. Just at the time one thinks they have solved all of life’s problems, life delivers a package of new ones, bigger than the last and with more intricate lacings. One of the lessons I was learning, and that I have tried to explain, is this: “Never complain about the air-conditioning in a private jet.”

This nugget came from riding in a Learjet in the 1960s on a Monkees tour. The model was new—more or less a converted fighter plane with plush seats where there used to be fuel and ammo. Five people were snug, and four comfortable, so it was pretty nifty for a band. The big problem was the huge air-conditioner vent that sat right behind the rear seat and blew out and over the back of it to cool the entire cabin. It had a gale-force fan, so if one sat in the rear seat, it howled like an arctic blizzard and blew like a Florida hurricane. It was a miserable seat, and it made for a miserable ride.

Hopping out of the Learjet at a destination, I complained about this to someone waiting for me and got a look I will never forget. It was a mixture of You dreadful spoiled rich bastard and What a no-talent jerk you are. Hence the admonishment to my loved ones: don’t complain about the air-conditioning on a private jet, and I don’t mean to do it here.

I have regularly looked to the skies since my mother’s passing and thanked her for her generosity and love. The money may have made me crazier than I was, but the money was providential and I will be forever grateful to her for it and for all the other good and selfless things she did for me. May we all be so fortunate.

But in the moment, Kathryn and I did not discuss this looming weight of the money, first because we were hardly aware of it, and second because we were caught up once again in our own infidelities—the residual of the beginning infidelities that had started our relationship, and thus provided no foundation for us, and the latest infidelity I had fallen into with another on my own in LA. Had there been greater intelligence at work and greater understanding, as well as a little self-discipline, then the money as madness might have surfaced as an issue to be analyzed. But there wasn’t, and it didn’t.

With the new money, the new business, my personal artistic career, and the philanthropic foundations all converging, I was in the confusing center of conflicting purposes, and something had to give way or grow together. I wanted to grow into an ability to manage all these things and not get run over by them.

With Elephant Parts now sitting on the shelf, waiting for a seismic shift in the media market, I hit another rough patch in finalizing The Adventure of Lyle Swann. Bill was called away to do a commercial, and I had to hire a new editor. There was no music, so I pulled something together for that. And I was running very far over budget. But we stayed afloat and steady through these little rapids, and at last The Adventure of Lyle Swann was ready for distribution.

Thankfully, Bill came up with the title Timerider, which took the place of my bookish Lyle Swann meta-reference title, and I set about getting distribution. I got nowhere with any studio or even old friends. I showed the movie to Jerry Perenchio, who told me it was the worst film he’d ever seen. Timerider wasn’t that bad; it was only that Jerry was that good. He had his share of dropped balls, but he knew a good thing when he saw it, so when he told me that Timerider was not that good thing, it was a real blow, even though I didn’t agree with him.

In the backwaters of the movie-distribution business I found a little company in Utah that agreed to distribute Timerider. It went out of business on the day the film opened. In a fit of despair and anxiety, I bought the distribution rights back from them, against the counsel of everyone in the Western Hemisphere, and set about trying to sell it to television and, through Pacific Arts, to the home-video market, which had finally peeked out from behind a lettuce leaf growing in the tangled agriculture of Hollywood movie studios.

However, Pacific Arts was too young and ill-equipped to handle these kinds of sales at that time, and Timerider languished on the shelf right next to Elephant Parts. Like a real Hollywood Movie Tycoon, I got my first taste of a Friday Night Flight, when the money flies away upon an opening of no sales, and now I had to learn how to manage the aftermath. I was learning quickly that money would not solve many of my problems; in fact, I was starting to understand how it would actually not solve any.

I had been more careful and thoughtful with the foundations than with Pacific Arts. The foundations’ wealth wasn’t my money, and my approach to that money was different from my approach to my own. I was in charge only of preserving and increasing as much as possible of the corpus and seeing that the foundations’ finances were used to the benefit of society and community.

The McMurray Foundation’s mandate was simple and straightforward: its grants simply needed to benefit women, and especially women in business. This was a joyful and most fulfilling exercise, and I started to love it more after each quarterly meeting.

The Gihon Foundation was a little more difficult, since it was generally focused on supporting the arts. While there was not too much in the foundation’s bylaws about how to do this, I’d had enough talks with my mother while she set up the foundation to have a good sense of the overarching spirit in which it was created. Gihon was the name of one of the rivers reputed to have flowed from the Garden of Eden and was a word my mother pulled from Mary Baker Eddy’s Science and Health, where it is defined as “the rights of woman acknowledged morally, civilly, and socially.”

I understood the intent of the Gihon Foundation, but not so much how to find a program for it. My mother had collected artworks for a while after she had the money and was in the process of building a museum for the foundation to hang them in. I didn’t know much more about what she intended, but I knew we did not have the money in the Gihon Foundation to continue to buy paintings. In any case, I could not fulfill her vision for the museum. I was sure it would have been beautiful had she built it, but I was also sure I couldn’t build it with her unique vision.

Understandably, many of the paintings she had collected were by men, but it occurred to me that it would be a good idea if they were all by women. This would serve two purposes. First, it would benefit women, which seemed right to me and in accord with the definition of Gihon my mother had used, and second, it would give me a point of departure for curating the collection. I had developed an artistic sense I depended on, but it was more focused on music, recording, design, writing, and performing and producing live events—not on paintings, about which I knew almost nothing. I couldn’t tell much of a difference between a good and a poor painting, but I could tell the difference between men and women. After some study and much conversation with art conservators and auctioneers, I sold the men’s paintings, and with the receipts from that, bought art by women, mostly on the basis of gender but also on the basis of aesthetics. To my relief and delight, the collection turned out to be impressive and high-quality.

My mother’s time raising me as a single mother was difficult, to say the least, and one of the elements that made these times so hard was the simple fact of the anxiety she suffered as a woman in a society and a culture that was controlled by men. She was pushed aside again and again for being a single mom—not an unmarried mother, mind you, just simply single—and from my vantage point as a ten-year-old boy and onward, I watched in despair and sorrow the way she was treated in certain situations by men who were not one percent her equal. To say the Gihon collection resonated with me as an adjustment for those times is a colossal understatement.

We created a program to send the collection to smaller towns, most of them without a museum nearby, and set the artwork up in high-traffic public areas like shopping malls and parkways and such. This way the people in a little city that might never see these paintings would get to enjoy them, and there would be the potential to inspire.

Foundations measure success with unusual metrics, and I found it hard to know whether we were actually doing any good. I discovered among other foundations a general tendency to count things up and bundle them together in a way so that the counting and bundling matters more than the things themselves. Many foundations count the number of vaccinations given and the number of meals served, and that becomes their measure of success. I was not moved by this tendency, however. To me a foundation’s metric needed to provide some idea of the importance—the spiritual and emotional value—of the foundation’s work and freely convey that to the public. The metric needed to take into account how good the meals were, not just how many were served, and to pass that value on as part of the nourishment. For Gihon, this was hard to do. Art traffics in good and bad, in aesthetics that call forward the spiritual senses and either satisfy them or not. As far as I know, there is no quantitative metric for that satisfaction. For me Guernica is one of the great antiwar statements, but I don’t imagine fifteen Guernicas would be any more impressive or make me any more antiwar.

Running the foundations might be enough to completely satisfy me as a life’s work, but without a dependable sense of the level of good they did, I would remain unrequited.

I had been brought into the foundations when I was dead broke, when my utilities were being shut off and food and gasoline were scarce in my household. It was hard for me to accept my mother’s invitation to become a member of the board and help her give her money away when what I wanted, and what I felt I needed, was for someone to give me a check. It was hard, but not impossible: after the first meeting I attended, where we made grants to struggling mothers, I was hooked. The emotional and spiritual return in this activity was overwhelming and much more significant and satisfying to me than sales numbers. The emotional high was satisfying in a way that making money was not, but I thought there must be a place where these two objectives could meet and where the emotional return meets the satisfaction of a profitable enterprise.

I was proving to have a lot to learn as a businessman, including how to exercise good business sense while keeping true to what motivated me and made me happy—to find among all this some sense of well-doing as well as well-being. I felt certain they were not mutually exclusive. I supposed they were likely mutually supportive, perhaps even symbiotic. I didn’t know if it was true, but it seemed worthwhile to try to find out.