Corny searched for one. He found a broken branch about two feet long. He handed it to Joby.

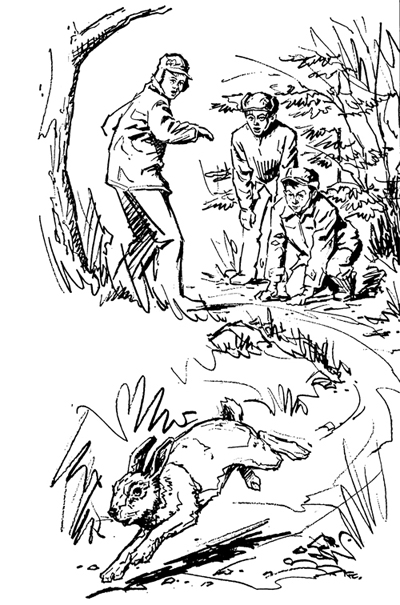

Joby took it. He looked at the club, and then at the rabbit. The rabbit was sitting still, its eyes big and wide.

Joby shook his head, and handed the club to Corny. “Here, you do it,” he said.

Corny took the club. He lifted it. The rabbit had not moved a bit.

Corny lowered the club. “Here. You do it, Rusty,” he said.

Rusty took the club. He looked at the rabbit. The tip of its short tail looked like a ball of cotton.

“Not me. I can never do it,” said Rusty. He flung the club away.

Joby crouched beside the animal, opened the trap, and the rabbit hopped away on its three good legs.

“His leg will heal,” said Joby. There was kind of a joy in his voice, as if it made him happy to let the rabbit loose.

Rusty and Corny both smiled.

“Come on!” said Joby. “There's one more trap left!”

Joby led them to the shore of the creek. The trap was set near the water, with half of an apple on it for bait. The bait had not lured any animal, though. The trap was still unsprung.

“Well, that's it,” said Joby. “Zero average. But I still think it's fun to trap!”

“You did catch a rabbit,” Corny reminded him.

“Yeah,” smiled Joby. “But rabbits are different. You can't kill them. They're like pets. You wouldn't kill your pet dog, would you?”

“'Course not,” said Corny.

They retraced their steps through the woods, and went back home. Rusty knew he'd remember that trip for a long, long time.

He'd remember that log, too.

Later, from the window of his living room, Rusty saw Perry Webb, Corny, Ted Stone, and several other boys walking down the road. Corny was carrying his basketball. As the boys passed in front of Rusty's house, Corny looked at the house. He said something to Perry. Perry shook his head, no.

Corny wanted to ask me to go with them. But Perry doesn't want me to. A lump rose in Rusty's throat.

A little while later Rusty got his own basketball and went outside. Dad had made a backboard above the garage door. Rusty practiced shooting long shots. He tried hard not to think of Perry and the others.

He practiced until his legs got tired. Then he went inside to rest. Sometime later he saw the boys returning. He could hear them chattering excitedly among themselves. Each was carrying a small bundle of blue and red under his arm.

Rusty knew what those bundles were. They were suits — basketball suits. Alec Daws had passed them out.

Rusty turned, stretched out full length on the easy chair, and gazed at his legs. They looked the same as anybody else's. But they were weak, slow.

Why did it have to be me?

“What's the matter, son?”

Rusty looked up. Dad was in the doorway, a tall man with dark hair and wide shoulders. His brown eyes were understanding.

“Nothing,” said Rusty.

“Nothing?” Dad chuckled. “I saw those boys walking up the street. They were carrying basketball suits, weren't they?”

Rusty shrugged. “I guess so,” he said.

“I think they were,” said Dad. “I heard the fathers talking about it in the store. Alec Daws is going to buy suits and form a basketball team. I think it's a wonderful idea. Good for the boys. Why didn't you go down and get your suit?”

Rusty looked at his father squarely. “Me? I can't make the team, Dad!”

“Oh?” Dad's brows lifted. “Who said you can't?”

Rusty put his elbow on the arm of the chair, sank his chin into the palm of his hand hopelessly. “I just know I can't,” he said.

“You might be fooling yourself,” said Dad. “Alec is a pretty square shooter. He's not trying to form a team of champions. He just wants a team. He wants to make it as good as he can, but he's not going to keep kids off who want to play. I've met Alec. He's a nice, decent guy.”

“I know,” said Rusty. “I met him, too.”

He put on his jacket, got his basketball, and went outside again. Even when his legs got tired, he didn't quit. He grew awfully hungry, too. But he still played.

Presently small flakes of snow fell. The flakes grew larger and began to stick to the ground. They fell on his cheeks, melting instantly. Still Rusty played, working on corner shots. He was sinking them better as the minutes dragged on.

Patches of white formed on the ground. Rusty moved about much more slowly now. He didn't run after the ball when he shot. He walked. He wanted to stay out as long as he could.

“Rusty, you've been out there for hours!” Mom's voice suddenly broke the silence around him. “Come into the house!”

He picked up his basketball, went in. He took off his coat and hat, dropped into a living room chair, and fell sound asleep.