Chapter Nine

Martyrs’ Monument and the Canal Hotel

As we neared the Army Canal we could see the Martyr’s Memorial (also called the Al-Shaheed Monument) to our left. It was dedicated to the Iraqi soldiers who died in the Iran/Iraq War. The Monument was opened in 1983, and was designed by Ismail Fattah Al-Turki. At that time Saddam spent lavishly on parks and monuments to glorify Baghdad and ultimately himself. Like the Roman Emperors of old, he aimed to pacify the unwashed by providing them with vast public buildings and amusements.

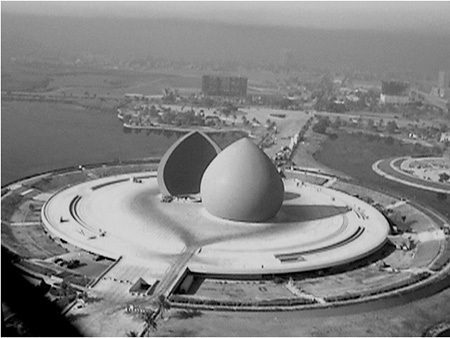

This Monument was built by Mitsubishi with Ove Arup the well-known company of Consulting Engineers at a total cost of $250 million. It was situated on an island in an artificial lake complex. The monument base consisted of two circular platforms, one above the other, each 190 metres in diameter on which the monument rests. It consists of an enormous 40-metre tall turquoise dome split in two resembling the domes of the Abbasid era as seen at Samarra. The two halves of the split dome are offset, with an eternal flame in the middle that represents the eternal martyr who is wrapped in the Iraqi flag. The circular wall on the platform displays the names of the more than half a million Iraqi soldiers who died in or are missing from the war. A museum, library, cafeteria, lecture hall and exhibition gallery are located in two levels underneath the domes.

The Martyrs Memorial (Al-Shaheed Monument).

Photo source: Global Security.

Map showing the proximity of Ar-Rashid Camp to the Canal Hotel and Sadr City. (The map is from the 2006 NGA Map of Baghdad. The legends in the serif font are the authors own).

This map was developed using materials from the United States National Geospatial Intelligence Agency and are reproduced with permission.

The Istikhbarat (Iraqi Military Intelligence Brigade) multi-storey prison was about 500 metres northeast from the Canal Hotel near the al-Rashid Military Camp and could be seen quite distinctly from the hotel. Curiously enough the UN drivers who were silent as regards Al Sha’ab told me that this was a secret service prison and had many underground levels in its basement where the prisoners were incarcerated and the unspeakable tortures were perpetrated on them. It also contained prisoners detained under Saddam’s form of ‘letter de cachet’ where the period of detention was indefinite and no information was released as to their identity or status. In early 1998 the 6th Special Republican Guard Battalion was stationed at al-Rashid barracks. Its main duty was to seal off the nearby Shi’a ‘Saddam (now Sadr) City’ quarter and shell it to rubble in case of mass revolt. This battalion had done precisely that in the slums of Basra during the Shia uprising after the Kuwait war. The prison was finally taken out in December 1998 by a smart bomb that entered through the roof, crashed its way down through the levels to explode in the basement. I never found out if there were any prisoners there at the time. In fact, I arrived at the Canal Hotel the following morning after a hectic dash down through Iraq as we evacuated the country. The female UN staff that had sheltered under the Canal Hotel stairs were still in a state of shock after the bombing of the night before.

Dennis Halliday, an Irish Quaker, was the UN Humanitarian Co-ordinator for Iraq and he operated out of the Canal Hotel. He was a person of sterling substance and integrity. He was respected by his staff and had their total loyalty. As an Assistant Secretary General of the UN, he had been responsible for Human Resources of the UN, in all a staff of 96,000 people. I met Dennis subsequently in Kurdistan many times at our meetings with the various Kurdish Leaders. I travelled to the Canal Hotel from my UNDESA base in the Saddoun Building at least twice a week. These visits were very popular as it had a modern canteen with Western type food and I used to look forward to the lunch there.

The Canal Hotel reflected the two UNs. The interior of the building was split in two with the normal humanitarian work going on in the half nearest the main gate. The door between the two halves was guarded by security personnel and a keypad controlled lock. Inside the protected inner portion of the Canal Hotel the UNSCOM Arms Inspectors had their quarters with a further protected area inside this area again for the British and US inspectors only. I was told that anyone outside of those two countries was barred from entering this special inner sanctum

There was a bustling social scene in the Hotel after hours. When a party was arranged by the military contingent for Saint Patrick’s night, Noel O’Regan, a fellow Irishman, and I decided not to attend as we felt that the UN, the military and a Saint Patrick’s night booze-up in a city where the children were suffering under UN imposed sanctions was not a good mix and would be offensive to Dennis Halliday, the UN and to the image of Ireland in Iraq. However, some years later I helped to hoist the Irish Tricolour over the British Army camp in Basra as Saint Patrick’s Day was celebrated there. In fact, they sidelined the war zone military rule of ‘two and no more’ for the night. Again some perverse instinct kept me away from the festivities as I maintained a sober decorum. Where normally at home I would consider it a pleasant duty to drench the shamrock I couldn’t in front of foreigners.

Saint Patrick’s Day in the British Army Base in Basrah International Airport. Left to right: Tom Lynch (Cork), John White (Limerick) (Both imprisoned by Saddam, see Chapter 8), Flip Labuschagne (South Africa), Steve Flint (Cork), Paudie O’Halloran (Cork), an Australian Army major and the author.

In any event these celebrations could not compare to a Saint Patrick’s Day I endured in Sevastopol in the Crimea. I got up early and hurried down to the hotel restaurant to find it closed. This unannounced closure was not uncommon in that part of the world. I stumbled out the door and down the main street in a driving blizzard hoping to find an open restaurant. Unsuccessful, I retraced my steps and returned to the hotel thinking wistfully of my family at home going down to Patrick’s Street in Cork, after Mass and a hearty breakfast, for the St Patrick’s Day Parade. I was then directed to what the locals euphemistically called a café and ordered what they had. This turned out to be cold, lumpy, porridge. It’s a morning I will never forget.

Most of my meetings in the Canal Hotel Conference Room were security briefings with the odd meeting on the progress of the 90-Day Report. For example, on Wednesday 28th January I was summoned to a meeting on security chaired by Dennis where we were assigned to Zones and Wardens were nominated for each Zone. The states of readiness were given colour codes starting with Green that entailed that transport was fuelled up and ready to go, that everyone had sufficient cash and that all papers were in order and that everyone had a bag of personal items of not more than 15kg ready for departure. The next phase was code Orange (for restricted movement) when non-essential staff were to stay at home and had all the requirements of code Green in place ready to be taken to designated concentration points. The next phases were Relocation and Programme Suspension to finally code Red… Evacuation.

Staff would be collected by UN transport at their concentration points and conveyed to the UN HQ at the Canal Hotel now designated as the Assembly Point. This meeting brought home to all of us that we were not in Baghdad for a vacation. Security awareness formed a large part of my time in Baghdad in the early days. I was issued with the ‘Guidelines for operating outside Baghdad’ when I arrived. It was couched in such a way as to absolutely discourage anyone from going outside Baghdad. We were frequently given security updates as the stand-off between Saddam and the UNSCOM (UN Special Commission) inspectors continued to deteriorate. We were given instructions on what to expect in the event of air strikes and how to cope with them.

Looking back on the situation I must admit that I felt safe. This was in contrast to the post-Saddam era when I was working out of Basra International Airport, the British Army main Base. One could sense the simmering hatred the liberated Shia Iraqis had for their liberators. To hammer home the point while there I was asked to go to Kuwait to attend a course given by the SAS on how to resist interrogation. I politely declined but I participated in a course on various IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices) and how to cope in the event of a roadside ambush and fire-fight.

In the middle of January, Iraq ceased cooperating with the UNSCOM inspectors claiming there were too many British and Americans on the team. It then denied the arms inspectors access to the Presidential palaces. These Presidential palaces were massive affairs. They had an area of a 60 acre farm and were protected by high walls with watchtowers every 50 yards or so. These watchtowers were occupied by a number of soldiers armed with machine guns. Inside the walls the palace proper would consist of a number of separate buildings scattered across beautiful gardens replete with many pools and fountains. A more correct term was that they were large palace complexes.

On 26th January we were informed that the US National Security Council had met over the weekend to dust off the military plans that had been drawn up the previous November. Diplomatic initiatives to end the crisis had been practically exhausted and with the arrival of the aircraft carrier HMS Invincible in the Gulf, the US and UK were planning unilateral military action with or without Security Council approval. President Yeltsin of Russia had sent an envoy to Baghdad to try to resolve the crisis. It was not anticipated that military action would take place before the end of Ramadan and that it would be preceded by an ultimatum of a few days.

By tradition the end of Ramadan is a hit or miss decision. I wrote to my youngest daughter and son on 28th January 1998:

‘Dear Daniel and Siobhan,

Just a note to keep in touch. Everything is fine here. If there will be a problem it will occur after Ramadan. Ramadan ends at the first sight of the new moon. A group of religious elders will wait tonight and if someone will go to them before 9 o’clock and tell them they have seen the new moon the elders will proclaim the end of Ramadan. If it is cloudy then they must wait and fast another day. It is expected that an ultimatum of a few days will be issued after Ramadan and then a number of strikes at military targets will take place outside Baghdad. We are quite safe with all sorts of states of alertness. At present we are in the second state. There are five in all. Number five is where you are waiting with a packed case for transport to go out of the country. So the position is not regarded as serious. If I have to go, Mum will be glad that I will have to leave some of my old treasured clothes behind.’

Meanwhile UN staff were to keep a low profile and stock up on canned foodstuffs etc. We were urged to operate on a Buddy-Buddy system and not to go walking near the Canal Hotel area after dark as it was heavily guarded by Iraqi military. On the 5th February we were again brought up-to-date on the situation. The staff that did not move into hub hotels, for greater UN control in the event of an evacuation, were admonished. Staff in general were admonished for excessive use of the radio system and urged to operate on the KISS principle – ‘Keep It Simple Stupid’. We were again advised that we would be whipped out if the need arose, the GOI (Government of Iraq) remained committed to ensuring our safety and that the same applied to those poised to carry out military strikes. On the 14th February we were told that the situation remained tense and precarious as one of the main issues was being resolved. Kofi Annan was sending a former Humanitarian Co-ordinator for Iraq, Dennis Halliday’s predecessor, Staffan Di Mistura and two technical assistants to define the maps of the eight presidential sites containing palaces for which the GOI requested special inspection arrangements. We regarded this as a good sign as in the diplomatic world such an initiative would not take place without prior agreement as to the outcome. The message ended with a Valentine’s Day greeting. In the event Kofi Annan’s meeting with Saddam was successful and the danger of conflict was avoided.

Looking back on those days I was not afraid as the situation played itself out. I looked on with a detached curiosity while those at home were worried sick as they stayed tuned to the TV news bulletins. On one occasion they actually saw me on television going through the entrance to the Canal Hotel in my Land Cruiser, where the representatives of the world press agencies were encamped throughout the entire emergency.

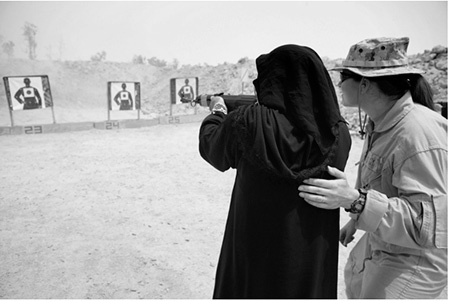

After work in my hotel room at night I watched Iraqi Television air their view of events and watched as platoons of middle aged civil servants marched and countermarched across the screen. Some of the civil servants were rotund gentlemen and they perspired as they struggled with their AK47s and indulged in some target practise. Sometimes squads of ladies were shown drilling and segregated groups were shown clustered around a sergeant as he demonstrated the workings of machine guns and RPGs. All of these scenes were aired with stirring martial music in the background. Again I felt sorry for those misfortunate people being forced into a war against modern adversaries with all the most up-to-date equipment and self-protection and having to face them with their vastly inferior armoury. Those who toil for oil have a lot to answer for.

Breaking one of the last taboos. Training a lady to kill as part of a training course for a Ladies Police Militia called “The Sisters of Fallujah”.

Photo source: Corporal Erin A. Kirk.

All means were utilized by Saddam to stir the people to a war-frenzy as this roadside mural indicates. The mural north of Baghdad shows Saddam and his army fraternising with Saladin and his. Saladin and Saddam are saluting each other. The image of the Man Himself was defaced after the invasion.

Photo source: James Gordon.

Shortly after the American-led invasion on the afternoon of August 19th 2003, during the insurgency, a lorry bomb exploded at the Canal Hotel and killed at least 22 people, including the UN Special Representative in Iraq, Sérgio Vieira de Mello, and wounded over 100 others. Sergio Vieira de Mello was President Mary Robinson’s successor when she resigned from her post as the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

To its credit the UN returned to the Canal Hotel as soon as it was prudent.