Chapter Ten

Freedom Frieze

I frequently had to go across the river to pass through what is now the Green Zone on my way to meetings with various ministries, to Odeh’s house and to various Trade Centres. The Green Area was also on the route to the Mosul Road when I was going north to Kurdistan and on the route to Amann when I was leaving the country. The Amman road took me past Abu Ghraib prison and I am sure that my high spirits at leaving Saddam’s Iraq for a few weeks would be severely dampened if I knew what was happening behind its walls.

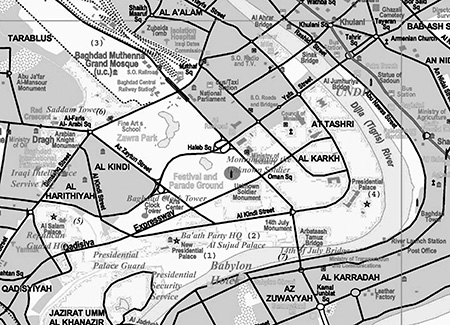

The Green Zone.

The Green Area opened up a fascinating part of Baghdad to me. When we exited the UN building we made for the large roundabout at Al Tahrer Square (Nasb Al Tahreer). This is the site of the Freedom Frieze (No.8 on the map), or Nasb al-Hurriya in Arabic; it is the largest monument built in Iraq in the last 2500 years. It was designed by the father of Modern Iraqi Art, Jawad Selim, and was to visually commemorate the Iraqi struggle for freedom prior to 1958.

The Freedom Frieze was erected over the entrance to the al-Umma park facing Al Jumhourriya Bridge. It consisted of 14 groups of sculpture each eight metres high and the total width came to 50 metres. It is mounted six metres off the ground and the 14 panels reading right-to-left are meant to represent a verse of Arabic poetry.

Selim was influenced by the cubists and by Picasso. The figures were reminiscent of the strands of Iraqi history and included old Mesopotamian and Islamic motifs. Through 1960 he worked on clay figures and sent them to Pistola in Italy, to be cast in bronze. They came back in pieces ready to be reassembled on site. Selim himself undertook the reassembly and erection. He was put under severe stress by the Iraqi Prime Minister, Abd al-Karim Qasim, who commissioned the sculptor to complete the project quickly to meet a deadline. When the second piece was being reassembled in January 1961 he collapsed and died from this stress; he was 42. His wife completed the erection of the frieze. It was subsequently commemorated on the Iraqi 250 dinar bill.

We turned left over the Al Jumhourriya Bridge and drove down Jafa Street along the northern border of the Green Zone on the left, with the Council of Ministers (RCC Building) just inside (No.9 on the map). We passed the Al Rashid Hotel (No.10 on the map) which was my hotel of choice when I abandoned the Babylon. It was famous for its unflattering portrait in mosaic of George Bush the Elder on its main entrance floor labelled ‘George Bush – War Criminal’. Everyone entering the hotel had to walk on the image of Bush’s face, which is regarded as a serious insult in Arab culture or indeed in any culture for that matter. This arose because a US rocket struck the hotel during an Islamic congress and many clerics were killed. The Al Rashid was particularly patronised by media people and CNN became world famous for their coverage of the First Gulf War that they reported from the roof of the hotel and were able to film the missiles as they cruised past on their deadly journeys.

The Entrance to the Hotel Rashid. It was dug up by US troops after the capture of Baghdad and replaced by an image of Saddam.

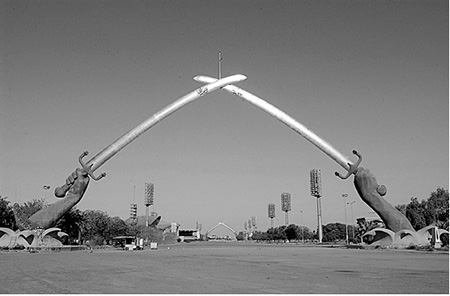

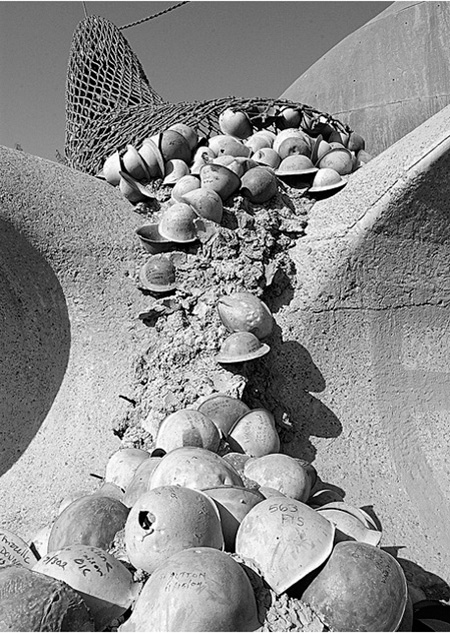

We then entered the Victory Parade Ground (No.11 on the map), officially the Sahet Alihtifalat Alkubra (Ceremonial Circle) parade grounds where Saddam staged his military parades. This area was dominated by the Swords of Qādisīyah (Qādisīyah was the site of a battle where the Moslem Arabs defeated the Persians in 636 AD and marked the beginning of the dominance of Islam in the region). These were two pairs of giant hands holding the crossed swords that were seen on the world’s TV screens each time, and they were many, when Saddam would stage his threatening military parades. The bronze hands holding the swords are modelled from Saddam’s own, even to the detail of his thumbprint. The stainless steel swords each weighing 24 tons are partly made from the guns and tanks of Iraqi soldiers killed in the Iran-Iraq war. The swords are 43 metres (140 feet) long and at their crossing point 40 metres (130 feet) above the ground they support a flagstaff. The sculpture was created from a sketch supplied by Saddam himself. The arms rest on concrete plinths, the form of which make the arms appear to burst up out of the ground. Each plinth holds 2,500 helmets of, what Saddam claimed, were those of Iranian soldiers killed during the war, and are held in nets which spill the helmets on to the ground beneath. This has echoes of the Assyrian Empire where the Assyrian kings would make a pyramid of the heads of the soldiers of the cities they conquered.

The Swords of Qādisīyah, also called the Hands of Victory.

Photo source: James Gordon.

The base of one of the Hands of Victory.

Photo source: James Gordon.

The Swords were numbered in the top 10 of the world’s war memorials. Today they are slowly disintegrating and there is a fear that they will be destroyed by the present Iraqi government in their drive to rid the country of all relics of Saddam. It is surely a case of ‘Sic transit Gloria Mundi.

The poem of Shelley measured in my head as I remembered the words of ‘Ozymandias’ (Ramesses the Great) where a traveller in the desert comes across some stones. It ends:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

The Victory Parade ground, or as I would put it, the Parade Ground of Death is a location that for me evokes Robert Service’s ‘The March of the Dead’. This is a poem of a victory parade when suddenly the victors appear to be replaced by their comrades who fell. I quote the penultimate verse:

The folks were white and stricken, and each tongue seemed weighted with lead;

Each heart was clutched in hollow hand of ice;

And every eye was staring at the horror of the dead,

The pity of the men who paid the price.

They were come, were come to mock us, in the first flush of our peace;

Through writhing lips their teeth were all agleam;

They were coming in their thousands — oh, would they never cease!

I closed my eyes, and then — it was a dream.

The area also contains the Monument to the Unknown Soldier (No.12 on the map) and the Baghdad Clock (No.13 on the map). They were also across the river from my hotel and were clearly visible from there. The Monument to the Unknown Soldier is inspired by the glorification of a martyr from the Iran-Iraq war. It is a huge 42-metre disc set into the ground at a skew angle. It is to represent a shield falling from the hand of a dying Iraqi warrior. There is an underground museum directly underneath the monument displaying artifacts relating to Saddam and his sons. The column beside it represents the Iraqi Flag and Flagstaff.

The Clock Tower had been built in 1980 to commemorate the first Arab Summit in Baghdad in 1978. This summit was called in the wake of the signing of the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty when Arab leaders were outraged. An image of this Clock Tower was on the obverse side of the Iraqi 100 dinar note. A number of ill-advised Iraqi snipers used the clock face as a firing position during the invasion in March 2003. A couple of well-aimed rounds from US tanks made history of the snipers and severely damaged two of the clock faces. This has since been repaired but two of the clock’s four faces have their hands permanently pointing at the time the clock was shelled at 07.52. For a few years the building under the clock hosted Saddam’s personal museum; it now houses Iraq’s Central Criminal Court.

The Baghdad Clock. The plume of black smoke in the background is from the site of a suicide car bomb. The Islamic shaped topped tower at the middle left of the photo is the Zawra Tower. It houses a restaurant on top with a viewing platform underneath.

Photo source: SSgt Cherie A. Thurlby, USAF.

The eating places of Baghdad could hold their own anywhere. In a laneway off the western end of the Karrada I discovered a great restaurant much frequented by the local Baghdadis. At the start of each meal the mezzas are produced complete with heaps of flat disks of bread. These are an assortment of salads used as starters, about eight of them and each big enough to count as a vegetarian meal. Chunks of bread are torn off the disks to sandwich portions of the mezzas and they are eaten with water or minerals. The joint, tikka or biryani is then put out and without exaggeration would be the equivalent of a family Sunday joint in the West. This is followed by the dessert, usually a large ice-cream concoction of mega calories. Finally, tea or coffee is served from a large Turkish type samovar paraded around the restaurant by an appropriately clad old waiter. The coffee would put hairs on your chest and the amount of sugar in the tea would be guaranteed to rot dentures. After a few visits a friendly waiter introduced me to mint tea and thereafter it was a must for me on all my visits. The total cost of this banquet would be less than three dollars. I could not help but ponder how come such an abundance of food in a country, with literally millions starving and what was done with the inevitable waste from each diner.

For special occasions, or during the visit of any chief from New York, we dined out at one of the many fish restaurants along the Tigris embankment in Abu Nawas Street. These are famous the world over for roasted Mazgouf, a Tigris fish not unlike carp. The restaurants are hives of activity each night and resemble any Western city shopping area on a Saturday afternoon. The entrance is on the footpath and just inside it is the cooking area with its large tanks of live fish.

Leading in from the kitchens, rows of tables straggle down to the water’s edge. Finally, planks lead out to pontoons complete with many more tables, each filled with diners. The Arabian music lends a magical air to the scene already enhanced by the chatter of the crowd and the smoke and aroma of baking fish.

The first duty of each host is to choose and point out the living fish in the tanks required for his guests. Immediately the tanks erupt into foaming turmoil as the fish try in vain to escape the hunting nets.

When the quarry is landed on the slab it is clubbed on the head and still writhing is instantly filleted. This operation is definitely not for the queasy. In fact, it is barbaric.

The fillet in its cage is inserted through the top opening of the oven. In contrast to my perception of fish cookery the baking time is quite long and many a bottle of Pepsi is consumed before the fish arrives on the table. The wait is well rewarded, as the fish is oily and luscious with mouth-watering flavours. As is the case with many visitors my eyes were bigger than my tummy and I ate much more than was prudent. I suffered a severe dose of Saddam’s Revenge for a few days after. It did not put me off the delicacy, however, and I returned many times to repeat the experience but in a more restrained and disciplined way.

At night I often dined with Noel O’Regan at a Lebanese Restaurant along Abu Nuwas Street. I used to get a taxi from outside the Hotel Babel to meet Noel in downtown Baghdad. It was cheaper to go outside the hotel, avoiding the taxis waiting there, and flag one down in the street. There was no restriction in doing this and to my mind gives the lie to journalists’ tales about Hotel taxi drivers being agents of the Mukhabbarat. Noel was staying in an apartment just off the Firdos Square and just around the corner from one of the Barracks of the Feddayeen Saddam. These were a militia of Saddam devotees that Saddam armed, trained and supported. It was forbidden to stop a car on this street and some very fierce looking guards, armed with an awesome plenitude of weapons, made sure the ban was observed.

After a visit to a liquor store for supplies we made for the restaurant. It had no nameplate outside the entrance that appeared to be a weatherbeaten, unpainted arched door at the side of the darkened street. There was a touch of mystery about the place reminiscent of the Hollywood black and white spy thrillers of the 40s and 50s. We would knock and a young man in Lebanese costume would open the door. Inside we would meet the major domo, a very old man similarly attired and with an ancient fez on his head. He escorted us to a curtained cubicle and when he spoke it was with a metallic resonance that drew attention to the condition of his voice box. We ordered a Coke each and while we waited for the kebabs we surreptitiously poured some of the libations we obtained in the liquor store, neatly wrapped in brown paper into the Coke. We were happy men as we solved one world problem after another, growing more knowledgeable and profound as the night progressed.

Funnily enough I rarely visited the Safafeer Copper Market. It is a very ancient institution and is even mentioned in the 1,001 Tales. This was an Aladdin’s cave with its gleaming artefacts and one was confronted with a bad case of over-choice. However, I brought home some beautifully engraved copperware. The copper workers there confined themselves to traditional ware that was more varied than the copper market in Sarajevo. However, their colleagues in Sarajevo capitalised on the siege of that city by selling engraved artefacts made from brass shell cases used by the combatants during the conflict. These found a ready market in the huge military presence of S-FOR troops who were hungry for such items. However, the Safafeer Market is in a sad decline at present in spite of the vast spending power of the US troops.

The antique shops with their stock of second-hand luxury goods also brought home the miserable lives people lived. Beautiful watches, rings and ladies’ jewellery were very cheap. Particularly sad was the number of gold Omega watches that Saddam presented to his generals and the Breitling ones he presented to his jet pilots. There must have been a very sad story behind each one.

I used to frequent an old gentleman near the Saddoun Building for my supplies of the large Phillie cigars that I smoked at the time. He stood at the corner of our laneway and displayed his goods on a tray that was secured by a strap around his neck. They were quite cheap and reflected the demand for tobacco products in Iraq; most Iraqis are chain smokers. This is easy to understand given the stress they have lived under all their lives. The cigarettes are reputably made to order on ships in the Mediterranean. Any brand can be produced with the correct packaging. A major health problem is building up in the country that will surface in the coming decades.

The ordinary Iraqi police were like their colleagues everywhere and confined themselves to their core activities such as traffic and speed control. There was none of the intimidation one could witness in Kiev at the passport control and the police on the beat there. On practically every Kiev street one would witness policemen standing in front of cars with the hoods raised as they checked car numbers on the chassis. Drivers would be frequently asked for contributions. This was also true in Bosnia where the Republic Serbska policemen would extort money from Bosnian drivers passing through their territory.

I was not long in Baghdad when I was presented with my UN Blue Passport. The office staff made a big fuss but I discovered later that it was practically useless and was largely ignored at passport controls throughout the world.