Chapter Thirteen

Tikrit to Sulaymaniyah

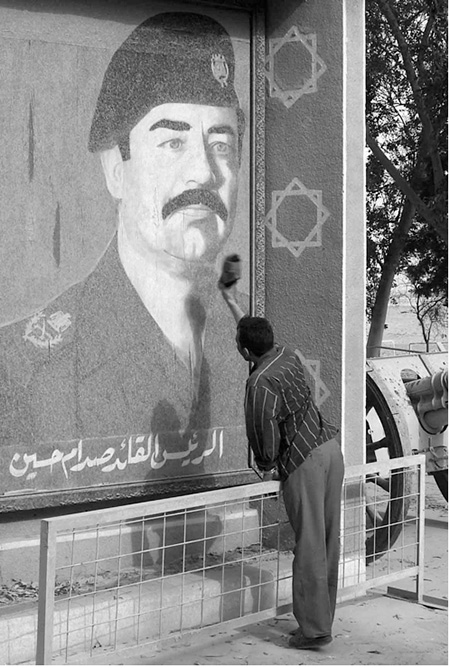

The road north forks at Tikrit, the right fork, Highway 4, took us to Sulaymaniyah via Kirkuk while the left one, Highway 2, went on to Dohuk via Mosul. Erbil was halfway on the link road between Dohuk and Sulaymaniyah. To avoid repetition, as we travelled both roads many times, I propose to give an account of each route in a generalized way in this chapter. On each route we passed many images of Saddam designed to remind and convince Iraqis who was the boss.

This is what happens when the boss is fired. An Iraqi takes his aggression out on one of Saddam Hussein’s murals outside Ar Rustamiyah Military Academy.

Photo source: CGSgt Eric S. Hansen, USMC.

On our first trip we went to Sulaymaniyah on Highway 4 so we passed through Kirkuk which is about 250 km north of Baghdad. It lies at the foot of the Zagros Mountains and is just south of the No Fly Zone, imposed by the UN to prevent Saddam attacking the Kurds. This No Fly zone was constantly patrolled by British and American planes operating from a Turkish Base. Kirkuk is an ancient city and is built on a mound containing the remains of a settlement dating back to 3000 B.C. The majority of the inhabitants are Turkomen with Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians and Armenians making up the rest. Kirkuk is the north Iraqi oil capital with this huge oilfield and its oil pipelines run west to Mediterranean ports. As we approached the city we noticed tall columns of sand, sometimes three or four of them dancing their way erratically across the desert as the wind created little cyclones. On later journeys we used to seek them out and drive the Toyota Land Cruisers through their base.

The Eternal Fire of Baba Gurgur (‘father of fire’ or ‘Saint Blaze’ in Kurdish) is a name used to describe the flames of one of the vent holes of the Baba Gurgur oilfield near Kirkuk. It is estimated that the burning flames have been around for more than 4,000 years. These were vents for underground gases forced up from the oilfield underneath. It seemed so wasteful to see so many megawatts of energy burn so fiercely in the middle of nowhere. They occur at all oilfields including those around Basra in the old kingdom of Babylon. It is believed that one of them was the fiery furnace of The Bible, in the book of Daniel, where the three Hebrew brothers Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-Nego were consigned by King Nebuchadnezzar. This was the usual penalty for those who would not worship the local god Marduk. Kurdish women still visit Baba Gurgur, asking to have a baby boy. This is an ancient practice and probably goes back to the time of their fire worshipping ancestors. Another theory is that they were the pillar of fire that guided the Israelites to the Promised Land. I have seen them in their full brilliance in the oilfields south of Basra. In fact, at night I could see them from the British Army Base at Basra Airport glowing on the horizon miles away to the south.

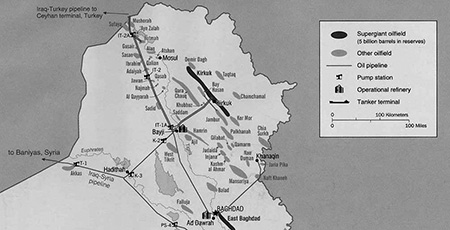

Oil was discovered at Baba Gurgur near Kirkuk on 14th October 1927 and its refinery was built and brought into production by IPC (Iraq Petroleum Company) in 1934. It used to produce up to one million gallons of oil a day and after 70 years of exploitation still has reserves of over 10 billion barrels. No wonder that Britain and the US are so paternalistic in their protection of the Iraqis. When I passed through the area I was reminded of a conversation I had with Shatha Kamel Chakmakchi, our accounts lady in the UN Sadoun Building, Baghdad: “Mr Dan” she said to me referring to the state of Iraq, “our riches are our greatest curse,” and this comment applies also to Kurdistan. The abundance of oil is the reason why Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran are implacable opponents of Kurdish attempts to set up their own state. The Kurds number some 29 million of people spread across northern Syria, northern Iraq, southern Turkey and western Iran and are the largest ethnic grouping in the world without a state of their own. Their tribal lands in Iraq stretch to Kirkuk and Mosul and the oilfields around these cities. The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), led by Masud Barzani, controls a part of the de facto autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan adjacent to Kirkuk. The KDP wants to make Kirkuk the capital of a Kurdish autonomous state if a federal solution will be arrived at in the post-Saddam Iraq. If there is any hint of this happening Turkey has stated that it will invade. An oil-rich Kurdistan could not be allowed to exist by their neighbours as they fear that it might expand its territory at their expense and annex the Kurdish areas of the surrounding countries.

Kirkuk Oil Field.

Source: CIA Map.

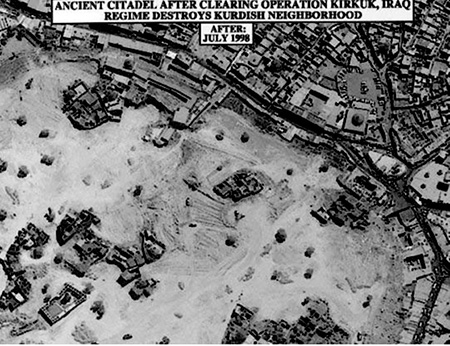

Saddam’s regime did its bit to ensure the Kurds would not retain their numbers in Kirkuk. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Iraqi regime destroyed over 3,000 Kurdish villages. The destruction of Kurdish and Turkoman homes was still going on in Iraqi-controlled areas of northern Iraq, particularly in Kirkuk during my time there. The modus operandi was that a convoy of Iraqi Army trucks would pull up one morning in a street in Kirkuk. The Kurds living there would be loaded on the trucks and were transported away mostly to execution sites. It was highly reminiscent of the clearing of the Jewish ghettos in eastern Europe by the Nazis. Some days later the trucks would return, this time loaded with Arab families who then settled in the former Kurds’ homes. This operation was particularly thorough in the streets of Kirkuk’s Citadel. This was part of Saddam’s policy of removing Kurds and Turkomen from the area and replacing them with Arabs and thus ensuring that Kirkuk and more importantly its oil would remain within the Arab ambit.

Dennis Halliday, the United Nations Humanitarian Co-ordinator in Iraq, was aware of what was going on and never lost an opportunity in every forum he had access to, to draw attention to it. As we passed through the city the famous Citadel crowned a hill about 130 feet high on the right of the main road and across the Khasa River from the city’s bus station. It was built between 884 and 858 BC by King Ashurasirpall II as part of the defences of Arrapha, the ancient city that occupied the site of Kirkuk. The Kirkuk citadel, like the ones in Erbil and Mosul, was an enormous structure with 72 towers on its defensive walls that surrounded its 72 streets. Many Kurds and Turkomen (a distinct Turkic ethnic group living in northern Iraq, notably in the cities of Erbil, Kirkuk, and Mosul) lived within its walls. A mosque within the citadel is reputed to contain the tomb of the prophet Daniel, King of Babylon, as well as the tombs of Hananiah, Mishael and Azariah. Religious tolerance was so accepted in Kirkuk that all religions desired to bury their dead near the tombs. Originally the site was a Jewish Synagogue then a Christian Church and presently a Muslim Mosque. However the tomb of Daniel is claimed by a number of cities and the probable place of his burial is Susa in Iran.

Kirkuk Citadel before September 1997 with its flourishing Kurdish and Turkomen buildings.

Source: US National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 88.

The clearance of the citadel. This ethnic cleansing took place during my first months in Iraq and no-one even mentioned it.

Source: US National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 88.

As it is just south of the 36th parallel, Kirkuk was not covered by the No Fly zone that protects the Kurdish area north of them. I saw some isolated low level short hops by Iraqi helicopters flying from their base and circling the south of the city. Some Air Force officers could be seen on the streets and an old MIG fighter on a plinth acted as gate guard at the entrance to the base. Saddam had a thing about MIG gate guards. He could have fought a decent sized war with the MIG21s he wasted on gate guards.

At the exit road out of Kirkuk and indeed out of all Iraqi cities we passed a long line of stalls selling drinks, fruit and crisps for the journey. The chips were sold in enormous cellophane bags and must have produced a mighty thirst. Interspersed with the stalls were petrol filling stations, Iraqi style, that consisted of rows of full jerry cans and barrels of gasoline complete with hand pumps.

Soon we passed through the northern city military checkpoint, left Kirkuk behind and headed for the border with Kurdistan. On the road north I soon began to realize what my mission was all about. Some High Voltage Transmission lines followed us all the way up. For a distance of 70 km each mast was either wholly on the ground or broken in two with the upper half leaning drunkenly back to the ground. It looked as if the tops were pulled down by trucks with wire hawsers. The destruction was complete. For the entire route not one mast remained intact. I estimated that to replace one line alone would cost $8.25 million and for part of the route there were many parallel lines.

Soon we drove through a barren area with many ruined and bombed-out villages. However, they were not devoid of life. One could see rows of tank gun barrels poking out over the ruined walls as Saddam’s Tank Brigades nestled in the homes they destroyed in Saddam’s savage campaign against the Kurds. Now they were menacing the Autonomous Region of the Kurds to the north. The scene was replicated in every former village we passed. One could see Iraqi conscripts walking along the road leading donkeys with panniers of water, filled from the adjacent streams, to service their comrades in the large camps dotted across the landscape. In many instances the conscripts were barefoot and wore their berets in a very casual manner like chefs’ hats. They certainly did not give any indication of being an elite fighting force. We passed many T54 tanks broken down on the road. The T54 had a notoriously unreliable engine and the old Iraqi ones would not pose much of a threat to any potential modern adversaries.

Further north the wide open plain was dotted by earthen-walled square forts each about an acre in extent and guarded at the four corners with small ZPU-1 and ZPU-2 anti-aircraft guns constantly manned by conscripts. Not much of a defence against supersonic planes with air to ground missiles I thought. Any future conflict with a modern Western army would result in slaughter for those poor souls and I felt genuinely sorry for them and their families. It must be remembered that this was a conscript army that endured sadistic discipline and as it contained Kurds and Shia and was ruled by terror. I have seen videos of a line of Iraqi soldiers being forced to shoot a line of their comrades who were sitting on the edge of a pit (their future grave) with their backs to their executioners. I also noticed that the senior officers on their constant visits between the various units traveled in battered civilian cars. This was obviously an army in decline. As we passed the destroyed villages and the Army that wrought such devastation on their countrymen the Kurdish drivers remained stoic and drove on without comment. At that time Saddam was still very much alive and the Kurds had to rely on the guarantees of powers that reneged on their promises in the past (Britain after World War One and the US after the First Gulf War). What must have gone through their minds as they saw their oppressors and their power right on their border and thought of their helpless dependants at home?

A damaged high-tension power line towers near al Durai’ya, Iraq, 17th March 2007. This mast was still damaged in 2007. Imagine similar damage to every mast on a line 60 or 70 Km long in 1998 in the sanctions era and the work required to reconstruct it.

Photo: Sgt. 1st Class Sean Riley, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division Public Affairs.

Soon we came to the last Iraqi military checkpoint before we crossed the border into the Kurdish Autonomous Zone; this checkpoint was the real thing. It stretched for about 200 metres along the road. Each vehicle was minutely searched by armed soldiers. There was an open shed where the men were body searched with an equivalent closed tent-like structure for searching the women. Nobody seemed to mind as they joined long queues snaking back from the search units, the women in their long black chadors chatted away as they awaited their turn. Once or twice an army deserter was discovered. I saw one of these unfortunates being kicked the entire length of the checkpoint area by an Iraqi army NCO. One could only speculate at the poor boy’s fate as he was thrown into a military truck and carried away. The people at the checkpoint, overwhelmingly Kurds, pretended not to notice and averted their gaze as their compatriot was brutalized in front of them. This was their reality in Saddam’s Iraq.

I noticed the long line of massive sanctions-busting oil tankers cruising slowly past. One Iraqi soldier was positioned beside their lane and as each truck passed him the driver dropped a number of Iraqi 250 dinar notes into his hand. It was said that this oil trade was a tripartite trade run by Saddam’s son Uday and the profits were shared three ways between Uday, the Kurds and Turkey. Our papers had to be processed by an officer and again the Irish passport evoked a friendly response. Soon we were on our way and crossed into the Kurdish Autonomous Zone. There was a palpable feeling of relief as we left the checkpoint and headed north through no-man’s land. We passed along a wide plain broken at times by rocky hillocks. We could discern old cemeteries with the marking stones distributed at random and at rakish angles. These were now forlorn as the villages around them, now ruins and heaps of stone, were slowly being reclaimed by the mountainous wilderness. This is what Saddam and his Anfal (The Spoils) campaign meant to the Kurds as ‘Chemical Ali’ bombed and torched their villages and slaughtered their menfolk. Soon we rounded a long swinging curve on the road and passed the outskirts of Chamchamal. It looked like a village but had 200,000 inhabitants and is recognized as the first place in the world where wheat was first grown. Shortly afterwards we reached the city of Sulaymaniyah where the Kurdish checkpoint was a more relaxed affair. Where the rest of the world would use traffic cones to delineate traffic lanes the Kurdish Pershmergas used shell cases and defused mortar bombs. The papers were examined and we were signalled on.