Chapter Fourteen

Baji Oil Complex

There was very little difference in the road from Tigrit through Mosul to Erbil and Dohuk. About 40 km north of Tikrit we passed through another oil-rich area. The place was awash with the flaming gas issuing from the fissures across the wasteland. We soon came to the Baji Oil Refinery complex. It is one of the three largest refineries in Iraq, producing with Al Dora more than 75 percent of Iraq’s refined products, making it one of the more important infrastructures in the country. After the invasion of Kuwait in 1990 Saddam sent a group of British citizens captured there to Baji and used them as human shields. The city was bombed during the Gulf war and badly damaged but was quickly put back in business. What the bombs failed to achieve was won in a canter by Sanctions and Bayi slowly ground to a virtual standstill for lack of maintenance and spare parts. It led to massive pollution in the area surrounding it and to a lesser extent throughout Iraq. Few of us who worked there will forget the all-pervasive smell of sulphurous emissions from the petrol driven cars and trucks. The complex was again extensively bombed in 2003 and suffered major damage but the facility is now back in business, employing 5,000 people and attaining an output of 350,000 barrels a day.

Our next conurbation was Mosul, Iraq’s third largest city. It has a strong ethnic mix of Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians and Turkomans. As it lay on the caravan route from India and Persia to the Mediterranean it became a strong trading centre. Mosul gave its name to the word muslin and cotton is still produced there. As it became a large regional centre it was home to a large military airbase that formerly dominated Kurdistan to the north. Mosul was within the No Fly zone so its airbase was then dormant. The only reminder of its former glory was the base Gate Guard, the ubiquitous Mig fighter on a plinth.

Bayji Oil Refinery, with our constant neighbours, the Zagros Mountains in the background.

Photo: Spc. Joshua R. Ford, US Army.

Mosul also has biblical associations. The ruins of the ancient Assyrian city of Ninevah lie just outside its northern suburbs on the eastern bank of the Tigris bordering the Erbil road. Nineveh, built between 704-681 BC, was a capital of the Assyrian Empire and thus capital of the known world. Its walls totalled 12 km in length and had 15 gates. It is the city that God commanded Jonah to preach to the inhabitants who were living a very sinful existence but Jonah decided he could realise his potential elsewhere and did not obey. On a sea trip he was swallowed by a whale and from within the whale he reconsidered his options vis-à-vis Nineveh so eventually he obeyed God, escaped from the whale and preached very effectively to the Ninevites. He is allegedly buried in the Mosque of Nebi Yunus (Prophet Jonah Mosque), built on some ruins of Nineveh.

I remembered Robert Ervin Howard’s poem II 11, the Assyrian King to his powerful city of Nineveh and describes its glory. The poem ends prophetically:

Cities crumble, and chariots rust

I see through a fog that is strange and gray

All kingly things fade back to the dust

Even the gates of Nineveh.

As the original Mashki gateway was of mudbrick Saddam reconstructed it. The lower portions of the stone retaining wall are original. The height of the vault is about five metres. Mashki means Watering Gate through which the farm animals were driven to water in the Tigris each evening. The Shamash Gate was named for the God Shamash the Babylonian God of the Sun.

The Al-Masqa or Mashki Gate, one of the fifteen gateways in the walls of ancient Nineveh. Did Jonah pass through here?

Photo courtesy of: Atlas Tours.

Mosul has a strong tradition of Christianity and I visited some of the local monasteries on my various transits through. It was uplifting to see the old monks with their Eastern type head gear (Shash) praying silently and at length in the sanctuary of their monasteries in a Moslem land.

On many of those trips I used to pass one of Saddam’s palaces. Its footprint covered 480 acres and contained 50 structures. Its boundary wall streched for a mile with guard towers manned by soldiers with machine guns every 100 yards. The main palace area had been extended in 1994 and as the extension was across the road from the ‘old palace’; privacy was catered for by building the security wall right across the nearby dual carraige roadway in order to encompass both phases of the Palace. The traffic had to make long detours to get around the complex. In 1998 around the time I used to pass it it featured in the controversy about UNSCOM inspections for Weapons of Mass Destruction and an aerial copy was shown to the media demonstrating its unusual features.

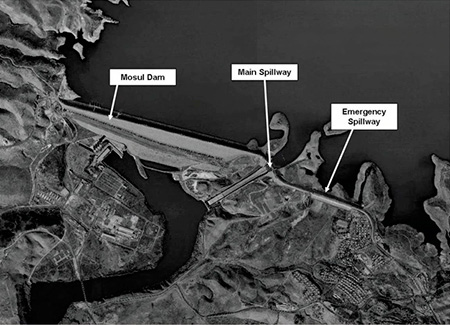

We would pass the Iraqi Border checkpoint shortly after leaving the city behind and witness the same activity as at the checkpoint north of Kirkuk. This checkpoint, however, had many more sanctions busting large oil tankers passing through. These went on to Dohuk and exited Kurdistan into Turkey at Zahko. After passing through the military checkpoint we would go on the eastern road to Erbil. The northern road to Dohuk would pass the large reservoir formed by the Mosul (then called the Saddam Dam) Dam on the Tigris River. The sun shimmering across the blue surface of the reservoir was a refreshing sight in this arid area. Mosul Dam is the largest dam in Iraq and its reservoir which covers about 385 square km holds 13.13 billion cubic metres with a maximum water depth of 80 metres. The main reservoir inflow is the Tigris River swollen by the snowmelt from the mountains to the north. The hydro power station has four 200 MW generators but was producing 320 MW at that time due to the effect of war and sanctions.

Mosul Dam showing its main spillway. A spillway is a gated chute that releases water when the water height in the reservoir reaches dangerous levels…

Photo: USACE.

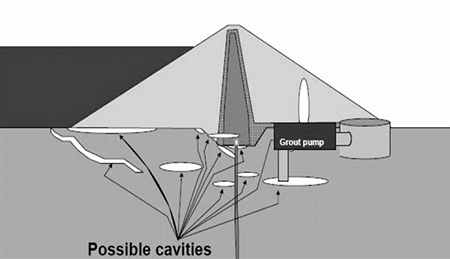

There is a major flaw in this earthen embankment dam. It is built on a layer of gypsum that dissolves in water and continuous maintenance is required to plug the leaks that constantly form at the base of the dam. Since the dam was completed in 1986 more than 50,000 tons of a special slurry has been injected into the leaks. These leaks manifested themselves even before the dam was commissioned and was losing 800 cubic metres of water per second. Two large slurry silos are stationed at each side of the dam and connected to a grid of pipes ready to pump in the slurry should any leak manifest itself.

Since the dam was built four large ‘sink holes’ have appeared, three of them downstream of the dam. These sink holes are caused by huge cavities appearing underground due to the erosoion caused by the gypsum decomposition. The earth overhead then collapses into the cavity to leave the sink hole. The leaks and these sink holes are the cause for concern regarding the stability of the dam. After the fall of Saddam the American Corps of Engineers issued a report in September 2006 stating that ‘In terms of internal erosion potential of the foundation, Mosul Dam is the most dangerous dam in the world’. They estimated a sudden collapse of the dam would flood Mosul to a depth of 65 feet (20 metres) of water and Baghdad, a city of seven million, to 15 feet (5 metres), with an estimated death toll of 500,000 to 800,000. I was unaware of this danger at the time and I am sure the UN did not know either. However, it was not within my sphere of responsibility.

Diagram shows the possible cavities under the Mosul Dam and The Grouting system in place to fill these cavities as soon as they are detected.

Image source: US Army Corps of Engineers.

One of the sink holes caused by cavities at Mosul Dam.

Photo source: US Army Corps of Engineers.

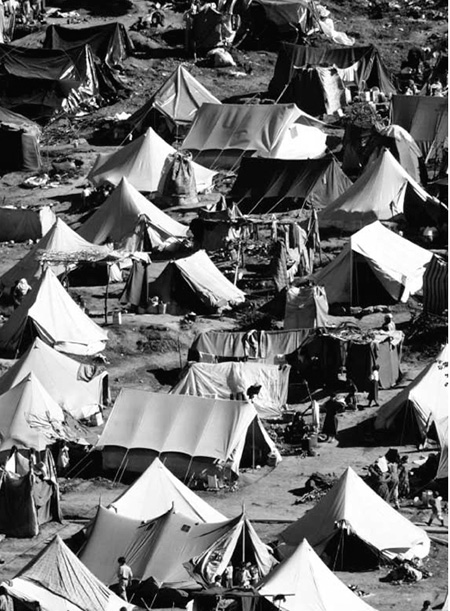

Leaving the reservoir behind, after passing through the Kurdish military checkpoint we turned right and passed the refugee camp where the Japanese NGO (Non Governmental Organisation), Peace Wind Japan, was doing heroic work catering for Kurdish refugees. It was a cold, wet morning with the rain pouring down in torrents. It was a pitiful sight. The tents were laid out in rows and covered with large black plastic sheets to provide extra protection from the rain, sleet and snow of a cold mountain winter. The winter temperatures here would fall below -15oC. The area between the tents was just a morass of mud. A visit out of the tent was unthinkable but it had to be undertaken by the children, the elderly and the sick. My heart went out to the misfortunate children dying inside and to their poor helpless and heartbroken parents. I thanked God that there were so many good people who came far from their homes and their own comfort to help. The Kurds are very familiar with refugee camps as the pictures below attest. However, they had no oilfields at the time and their plight was largely ignored by the powerful. The one exception was the British Prime Minister, John Major, who was responsible for the setting up of a safe haven for them at Amaydia. When we passed this harrowing camp we reached Dohuk.

Refugee tents cover the mountainside in the Kurdish refugee camp of Yekmel in 1991. This camp looks relatively comfortable in the spring sunshine.

Photo: PH2(AC) Mark Kettenhofen, U.S. Navy.

Dohuk nestled at the foot of some precipitous mountains to the north. We could see the lights in the window of a small blockhouse on top of one of the peaks. This was a Kurdish observation post and considering that the temperature in the city was -15oC it must have been cold, cold up there. No wonder the Kurds are such formidable warriors having to endure this type of environment. It was very reassuring to the city folk to see the lamp flickering in the tiny window so far above them.

The warehouse was next to scrubland and this produced some unwelcome visitors, snakes. One had to be very careful when lifting equipment in case one would disturb a resting and very cranky reptile.