Chapter Nineteen

Baghdad Jesuit College

I decided to set up my headquarters in Erbil which was the largest city in the Autonomous Area having over a million inhabitants. It also had the advantage of being halfway between Dohuk and Sulaymaniyah. The UN compound there was situated in Ankawa, a suburb in the northwest of the city adjacent to the new international airport built there now. The UNDP office and the UN Guest House as well as all the UN Agency and NGO offices were located within a hundred metres or so from Kevin Farrell’s HQ.

I settled in well with the local UN staff in Erbil. The UNDP/UNDESA office manager was Azziz Ahmed, a large man with a size 50 waist, as I discovered when he later asked me to buy a pair of denim jeans for him on one of my visits out of Iraq. Azziz Ahmed was tall and bespectacled and had a facial tic that was very obvious when he was under pressure. He was a chain smoker and from his appearance, if he were a Westerner, would be labelled as a ‘pint man’. It was unusual to meet a drinker of alcohol in Iraq so when I enquired about Azziz’s beverage preferences I was informed: “He is known to sink a few.”

He smoked about 60 to 80 cigarettes a day. Cigarette smoking was rife in Iraq and cigarettes were very cheap. As a matter of fact I had developed a liking for American ‘Phillie’ cigars while in Baghdad and contentedly puffed my way through each day enveloped in a dense smelly cloud around my desk and filling the office. It became so bad that our tea lady-cum-cook, Khajal, used to stick her head into my office every hour and liberally spray the place from the door with a can of equally smelly deodorant. Iraq had some similarities with Ukraine where I had worked some years previously. Both suffered under brutal dictators for long periods and each took their own measures to cope with the position they found themselves in. In Ukraine alcohol was the solution. There vodka was cheaper than bottled water and at election time one political party distributed their own branded vodka free to the masses. In Iraq tobacco was the poison of choice. In future the health services of both countries will have to cope with the results.

Aziz was our interpreter at all meetings with the government ministers and the local electricity company engineers. We became friends and spent many an evening in the UN club, up the road from our office, playing billiards on the full-size billiard table there. While there we polished off many a can of whatever brew was available. Our temperaments suited each other. Being an Irishman I had a soft spot for the underdog. In Baghdad I was a very partisan supporter of the Iraqi man in the street and while in Iraqi Kurdistan I was a firm and very sympathetic supporter of the Kurds. He was witness to my performances when any conflict would break out with Odeh, the numerous visiting UN missions and with UNDESA in New York. Being an interpreter he was also witness when I crossed swords with some of the Kurdish officials: “Mr Dan is a fighter” was the highest accolade I could have received from him. He became very worried when I threatened to resign when some problems became intractable and using his behind the scenes influence with the Kurds he ensured that the problems resolved themselves.

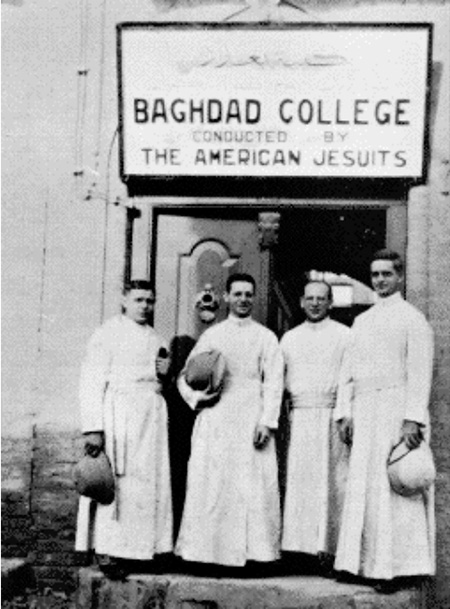

He acted as our Liaison Officer to the government in Erbil and had very good English having been educated from a very young age in Baghdad College. This was the famous and prestigious Baghdad second level college founded by the Jesuits and from the beginning catered for Christians, Moslems and Jews. It is the Iraqi Eton where the sons of the elite were educated. It boasts of several well-known alumni and countless Iraqi professionals and intellectuals now living throughout the world. It was founded in 1931 at the direction of Pope Pius XI by a group of four American Jesuits from the New England Jesuit Province. It concentrated on providing a solid education rather than proselytizing and in time it attracted pupils of all religions.

The four Jesuit founders of Baghdad College.

During the 1980s, it was patronized by the sons of Saddam’s elite including Qusay and Uday Hussein, the non-academic sons of Saddam, each terrorizing students and staff and flouting the school’s strict rules. Omar al-Tikriti, son of Iraqi Mukhabarat Director Barzan Al-Tikriti, ran for student representative. When he received only two votes, his bodyguards beat the winner, leaving him paralyzed. Incidentally when his father, Barzan Al-Tikriti, was captured by the Americans he was sentenced to death. He requested to be hanged with Saddam but transport difficulties on the day made this impossible. Suffering from cancer of the spine he was hanged a few days later but the hanging itself was botched and he was decapitated in the process.

The Financial Officer in Erbil, Farhad al Mullah was also educated in the same establishment as was Imad Khadduri. This meant that I had at least three graduates of the Eton of Iraq working in the electricity sector. I had met Farhad in Baghdad many times as he made his monthly trip with his financial balance sheet and returned with a few thousand dollars to run the office for the following month. Farhad was happily married in Erbil with a young family, and most unusually for a Kurd, used frequently to push the pram, when out on a Friday’s walk with the family. He was very refined and was a gentleman to his fingertips

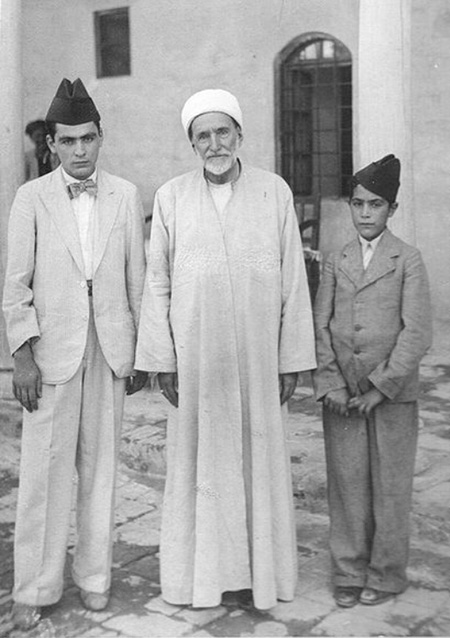

His grandfather was the famous Mulla Effendi of Erbil who came from a prominent Muslim clerical family that spent their lives preaching and teaching in the Great Mosque in the Citadel of Erbil since the 16th century when the family had to leave Persia. He was famous for resolving grievances among the tribes and was decorated with the second highest honour of the Ottoman Empire by the Ottoman Sultan. He was part of the successful representations to the League of Nations to have Mosul included in Iraq in 1924. He supported the rights of the Christians of Ankawa (A Christian suburb of Erbil). During the revolt against the British in 1941 the Iraqi Royal Family, who were puppets of the British, took refuge in his house, the Badawa Palace in Erbil and in gratitude King Faisal decorated him with one of the highest Iraqi honours.

Mulla Effendi with his sons Izaddin Effendi (left) and Qasim Effendi (right) at his palace in Badawa in the 1930’s.

Mulla Effendi had two sons, Izaddin and Qasim, Izaddin was Farhad’s father. Farhad told me that his father had been a minister in King Faisal’s government and that he had a photo of him with Eamon De Valera at home. He promised to find it for me. His father was writing his memoirs at the time, but died when I was working in Erbil, so I never saw the photo. I went to his funeral in a local mosque and caused great hilarity among the local UN people when they saw me kneeling on a prayer mat and copying, albeit very awkwardly, the motions of the people on either side of me. Farhad’s family formerly had extensive land off the Erbil to Mosul road near Erbil but it had been taken over by Saddam’s Government.

His grandfather was mentioned in many books including Hamilton’s book A Road through Kurdistan as ‘the rich and pious Mulla Effendi who owns large tracts of land around Arbil and whom I always heard spoken of as a wise and kindly man’. Effendi is an aristocratic title somewhat akin to ‘Sir’. So Farhad was an aristocrat and it shone out with his pure enunciation and gentleness of manner. Indeed many of his family have achieved prominence in the public life of Kurdistan. A cousin of Mulla Effendi was one such; he was called Ahmed Uthman Effendi and held many important posts in his lifetime. He was appointed Governor of Erbil and later Governor of Sulaymaniyah and Senator and one of the gates in the Erbil Citadel is named after him.

Aziz’s cousin Nian Simko was the office secretary. She was a beautiful lady and a native of Sulaymaniyah. Her dad was a school teacher there and I visited their house a number of times. Nian was typical of the modern Kurdish woman with great independence of mind and like many a Kurdish girl she found her feet when she went to university.

The original Erbil office staff when I arrived, from left, Azziz the office manager, Nian the secretary, the author, Khajal the cook, Farhad Rassam the driver and Farhad al Mullah the financial officer.

My driver was Farhad Rassam, a Christian, who lived across the road from St. Joseph’s Cathedral, about a hundred metres from the office. He had been in the Iraqi Army and took part in the invasion of Kuwait. He was lucky to be detained by the British after the hostilities. When he was released he was headhunted by the Iraqi Army and was offered a commission in the Republican Guard. He declined the offer and when his military service came to an end returned home to Erbil. He was married with two daughters and I often spent a pleasant evening in the house where he and his family lived with his parents. He had a beautiful wife who wore all the latest Western clothes including jeans. I noticed, however, that the Moslem custom of the women staying in the background when visitors were in the house was practised there. One evening I was invited to a meal in Farhad’s house with the Archbishop of Erbil. However, I made my excuses as I wasn’t used to sophisticated and civilised company, having spent many months in the macho world away from what Caesar called ‘ad effeminandos cultos civitatis’ (far from the effeminating influence of civilisation). I used attend Sunday Mass in the Cathedral of St Joseph’s. This was held at 5.00am and it was inspiring to see so many Christians going to the mass so early on a morning of what for all of them was a normal working day.

The Cathedral of St. Joseph’s was my Parish Church in Ankawa. It is presently a rallying point for the persecuted Christians of Iraq.

The Christians exist largely in villages that have held on to the religion of their forefathers since Thomas the Apostle converted them on his way to India so long ago. Later on they were part of the Nestorian heresy but ultimately came back to union with Rome. They are now known as the Chaldaens. I visited some of their monasteries with Farhad and it was significant when one priest admonished me for the bad example the Irish were giving the world in what he perceived was a Christian civil war in the North of Ireland. The Chaldaens use Aramaic (the language of Christ) and Syraic in their religious ceremonies and I was shown prayer books in this language. I was informed I could get these books in Baghdad but I never got the opportunity to investigate. There were 500,000 Chaldean Catholics in Iraq at the time. Though they are in union with Rome, when I attended their Easter ceremonies they appeared to be similar to the old type ceremonies in vogue prior to Vatican Two Council. When I was a child in Clonakilty I thought that the Holy Week Tenebrae would never end and the feeling was similar in Erbil. In the crowded church the archbishop appeared old and vulnerable on his throne. The congregation filled every space and I remember an old man sitting on the kneeler of the altar rail and studiously cleaning between his toes with his fingers right through the ceremonies.

When I was invited to the wedding of Farhad’s sister the congregation was female dominated and I seemed to be the only male in the church aside from the groom. There were sporadic outbreaks of ululuing throughout the ceremony and when it was over the whole congregation of women trotted after the bride and groom through the streets in the dark to the wedding reception still ululuing loudly. The reception was held in a large enclosure with a platform at one end. Here the happy couple sat on thrones and the wedding party sat at numerous tables scattered around the grounds, each table providing their own wedding repast. The wedding guests then formed a line and each guest approached the newly married couple and presented their wedding gifts. I thought this was a very civilized way of conducting a wedding instead of the wasteful, ostentatious and expensive banquets of the west.

Religious tolerance seems to have taken a beating from the Islamic extremists post Saddam. Between 2003 and 2010 67 churches in Iraq have been bombed, 3,000 Christians have been killed and about half a million have been forced to leave behind all they have and flee to other countries. They live in fear because of organized terror against them including murder, kidnapping for ransom, torture and demands that they should convert to Islam or leave the country.

Chaldean Christian refugees in Jordan. Note that the men are in the background. This resembled the Irish custom during the Penal laws when men formed an outer defensive cordon as the women attended Mass at remote and hidden mass-rocks.

Photo: Tasher Bahoo.

When I visited Baghdad with Farhad we often called to his aunt’s house, a pleasant detached bungalow located in a Christian enclave just off the Karrada. I often wondered later how the poor lady fared during Bush’s ‘Shock and Awe’ bombing campaign. When Farhad came to collect me from the Hotel Babel during these visits, I noticed that he used to converse with the two beautiful ladies who manned the reception desk of the hotel. They looked like twins, they were tall, slim, dark and beautiful with very refined complexions framed by long black hair. Farhad told me that they were Assyrians and they were keen to get news of home.

I located a Chaldean church in Dohuk quite near a madrassa (a moslem seminary) but I failed to locate a church in Sulaymaniyah. In general Christians tended to keep a low profile as the memories of the Armenian and Assyrian massacres at the time of the First World War and the later Simele Massacre of August 1933 are still potent in their memories. They also remember the fate of the Jewish communities who lived in their own villages down through the ages who were expelled from Iraq after the Six Day War. The Jewish families were traditional carpet weavers and one evening I managed to procure one of their beautiful rugs at a wayside stall in Dohuk.

Quite a few Assyrians lived in the suburbs of Erbil. They were mostly Christian and were the remnants of a once great empire that was the super power of the ancient world. They ruled by terror and I mean naked terror. They have left many accounts of their methods on the clay tablets that were discovered in Nimrud and Nineveh. In the annals of Assur-Nasir-Pal he recounts his exploits during a typical day’s work when he visited some rebellious cities. He flayed some of the rebel nobles, then heaped their bodies in a pile and topped off the top with more of the rebels impaled on spears. He lined the city walls with the skins of yet more flayed rebels and cut off the limbs of the remainder. All in all a charming man.

While Assur was the first capital of Assyria, Nimrud was the second. It was quite large and its city walls were over eight kilometres in circumference. Nineveh was the third and final capital of Assyria and was even bigger. By 1400 BC it was the most powerful country in the Middle East but it was finally destroyed by the Medes of northern Persia (the ancestors of the Kurds) and their allies in 612 BC. The Assyrians have a long history of oppression and have had to defend themselves almost continuously in the past, even their priests needed armed protectors.

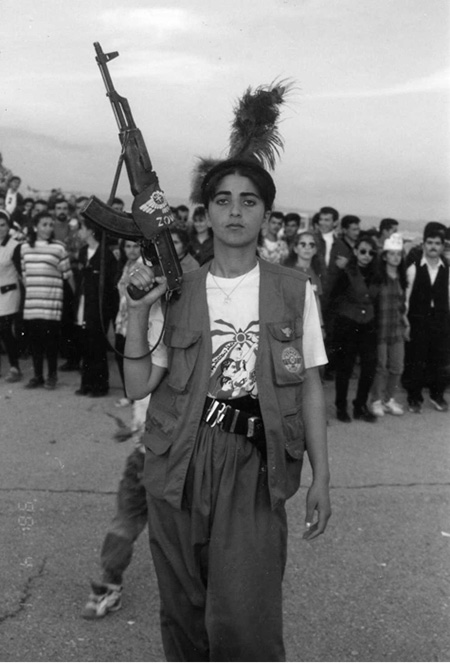

The desendants of the Assyrians still maintain their own traditions. In fact, I came on one of their New Year celebrations with Farhad one spring evening just outside Ankawa on one of Saddam’s abandoned air bases. The festival is called Nuw-Roz and is usually celebrated on the 21st March. The person of honour wears a head dress of cockerel feathers and the whole group dances around to Assyrian music waving the Assyrian flag. The person of honour in this instance was the leader of the Ladies Assyrian militia. A beautiful lady she was, dressed in khaki with a white T-shirt sporting the Assyrian flag. She took her military job seriously as she danced with a pistol in her belt occassionaly brandishing her AK-47. I felt very honoured when she took off her crown of cockerel feathers and placed them on my head. She was a very brave lady to publicly give witness to her beliefs. Remember that Saddam was still in Baghdad and had many agents in Kurdistan. When I was aware of who she was I noticed her frequently thereafteron on my travels, flitting in and out of cover and scrambling up steep rocks as she put her militia through its paces.

The Leader of the Ladies Assyrian militia. Note the symbol of the ancient Assyrian god Ashur on her AK-47.

The author at Nuz-Roz with Farhad and friend.