Chapter Twenty Five

Korek Astronomical Observatory

In the early 1970s the President of Iraq, Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, decided that the country should emulate their ancestors and enter the mainstream of science. Astronomy was one of the sciences he decided on and it was introduced as a subject in second level and in University curricula. At his behest the Iraqi National Observatory was built on Mount Korek in 1973. Its first Director was Dr Athem Al-Sabti who is now on the staff at the University of London Observatory.

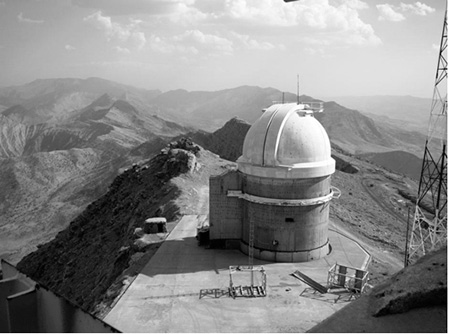

The Observatory is situated on top of the 6,716-foot high Mount Korek. Due to its remote location it was an ideal site for astronomical observations as it was free of urban light pollution. The Observatory, which cost $160 million to build, sported three telescopes in its heyday, two optical, one with a 3.5m mirror and the other with a 1.25 metre mirror but due to war conditions these optics were stored in safe locations. My friend Rojgar Hamid informs me that the 3.5 metre mirror is stored in one of the University of Baghdad’s warehouses in Jadriayah. The third was a radio telescope with a 30-metre dish.

The road up to the Observatory on Mount Korek.

Photo courtesy of Rojgar Hamid Ali.

I visited the Observatory one day as we were working in the vicinity. There was a road of sorts going right to the top of the mountain and our wheels just fitted the narrow track.

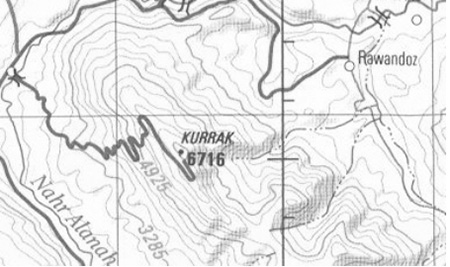

The Corkscrew Road to Mount Korek. (From the Irbil Region (joint operations graphic) original scale 1:250,000 Defense Mapping Agency Series 1501, Sheet NJ 38-14, Edition 3, 1991 reprinted 2002 map.

Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

I marvelled that we were actually driving to the top of a steep mountain 6,716 metres high. When I was at school in Cork during the 1950s a local daredevil, Joey Kerrigan, went to the top of Ireland’s highest mountain, Carrauntoohil in County Kerry, to us then a mind-boggling 1,038 metres high, on a motorbike. We marvelled at Joey’s feat but in comparison Carrauntoohil would be counted as a boulder on Mount Korek.

As we neared the top we passed a row of modern houses. These had been built for the astronomers but were now deserted and looked as if they had been trashed by the Kurdish Peshmerga. It would take a brave soul indeed that would live en famille in such a place. I could not imagine Western women agreeing to live there or to bring up children there. It was no place for bachelors, but would have been perfect as a remote monastery for the early Christian Fathers. When I was there I felt as the ancient Mesopotamian priests must have felt at the summits of their Ziggurati. I felt separated from the earth and the affairs of men and felt almost exaltation as I looked over the adjacent mountain tops and felt I was very near the spiritual world. For some reason it reminded me of the monastic settlement of Saint Finian on Skellig Michael on an Atlantic rock off the coast of Kerry. When the early Irish embraced Christianity in the 5th Century they meant business and the early monks set up their monasteries in remote inaccessible places. They wanted separation from the distractions of men and sought solitude in order to communicate with God. One such place was Skellig Michael a 230 metre rock in the Atlantic off the coast of county Kerry in the 7th Century. The hardy souls who lived there in their monastery of primitive stone bee-hive huts ensured they were far from the temptations of the flesh.

For years scholars have speculated that Celtic Christianity had its roots in the Coptic tradition of the Desert Fathers of Egypt who located their monasteries in remote areas of the desert to be nearer to God and the Irish emulated them in their remote sanctuaries in the Celtic wilderness. The Coptic tradition came to Ireland via Gaul and bypassed Rome. Indeed there were frequent clashes between Rome and the Celtic Church of Ireland. This most famously manifested itself in the different dates for Easter arrived at by both traditions and the type of monastic tonsures the monks affected. The Roman Church insisted that all Christians should celebrate Easter on a date selected by Rome. In time all of the Irish monasteries obeyed Rome but the monastery on the Skelligs refused to conform. Catholics were forbidden to marry during Lent and when the Roman Lenten period commenced on mainland Ireland the Skellig Lists would be prepared in each parish. All unmarried people of a certain age would be listed and great fun would ensue as they were paired off by the village people. The list of the Skellig pairs would be published and displayed in a public area to the intense embarrassment of the unmarried. As the Skelligs Lent began a few days after the Roman one the people on the Skelligs list could still marry during those few days. However, the difference in dates gave rise to a much darker period of Irish History. The only English Pope, Adrian IV (Nicholas Breakspear), issued the papal Bull ‘Laudabilitur’ that ceded Ireland to the English King Henry II so that he could bring all of the Irish Monasteries under Rome’s control. So it can be said that Skellig’s style of Christianity is indirectly responsible for the 800 years of bloodshed, famine and slavery that followed.

The scholars view that there was a link between the Celtic Church and the Egyptian Coptic one has been given a great deal of credence lately with the discovery of the Faddan More Psalter. This was an early Celtic Christian illuminated manuscript found buried in a bog of the same name in north Tipperary in 2006. It is reckoned to have been produced in 800 AD. What rocked the scientific establishment was the discovery of fragments of papyrus within its cover. All Irish manuscripts are scribed on vellum so the scholars are convinced that there is now a link between the Irish Church and the Middle Eastern Coptic one that used papyrus. This view was given further weight when the stiffening inside the cover of the psalter was revealed to be of Egyptian Coptic origin. So it would appear that there are many influences in the Irish psyche from the ancient Middle East.

Skellig Michael home to an ancient monastic settlement off the Kerry coast with Sceilg Beag in the background.

Photo source: Fáilte Ireland.

Soon we got our first glimpse of the Observatory proper as the two optical observatories came into view. There was an array of communication towers interspersed between them. Two large holes disfigured the copper dome of the largest building. We reached the top and entered a huge hall where we were surprised to meet a section of Peshmergas. It transpired that they were there to guard the vital radio equipment and the radio masts. Due to its height and communications facilities Korek was of great strategic and military importance to the Iraqis when they were in control there and now, of course, to the Kurds. The Peshmergas were drinking tea, sitting around a campfire in a corner of the hall and invited us to join them. It was the first time since I left the Ukraine that I drank tea made in a samovar so I cast qualms concerning hygiene aside and joined them.

The Observatory hall was cavernous and we gingerly climbed to the base of the huge copper dome. There were two large jagged holes in the copper forming the dome itself. The Peshmerga said the largest hole was caused by a missile fired from an Iranian plane in 1985 during the Iran-Iraq war. It was attacked also by the US Air Force in 1991 during the Gulf War when the second, smaller hole was inflicted. Here everything was enormous; the wind howled and shrieked through the massive holes made by the missiles and the smaller holes made by machine gun bullets.

This photo demonstrates the size of the Iranian Missile entry relative to the photographer.

Photo courtesy of Renas Ismael.

I ventured outside and walked around the perimeter of the site. I must amend that statement and say, within 10 metres of the perimeter. There was an icy wind howling around the structure making eerie noises as it tore around the masts and steelwork. It was difficult to stand upright and much as I admired the spectacular view over the surrounding peaks I had no desire to be plucked off by the wind and take flight over them.

With the fall of Saddam’s regime scientific relations have again been established between Iraq and the outside world. Academia in Iraq has taken a leading role in restoring the study of Astronomy from the Ministry of Higher Education in Baghdad, Baghdad University and the Iraqi National Academy of Science. This has led to the rebuilding the damaged Observatory at Mount Korek by the Kurdistan Regional Government. More importantly the University of Salahaddin in Erbil, capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, has taken particular interest in astronomy and the Observatory.

Astronomy has attracted a large enthusiastic amateur following in Kurdistan. The Amateur Astronomers Association of Kurdistan has its own sophisticated website www.kurdastro.org and its vice-president, Rojgar Hamid Ali came to my assistance with an offer of free access to his photos when my own were mislaid. This offer was also extended by his colleague Renas Ismael. They regard themselves as ‘Astronomers without Borders’ and maintain that ‘Boundaries vanish when we look skyward’. Another laudable motto is ‘One People, One Sky’. The Kurdish Society has affiliations with a multitude of international astronomical societies. Their co-operation with the Iranian Astronomical Society bodes well for international understanding. The Kurdish astronomers have taken on the heritage of their forefathers and maintain the same approach as their ancestors to astronomy. They are the true descendants of the Sumerians, the Babylonians and the Assyrians who have brought so many skills to mankind. It is a source of great sadness to me that people with such a rich heritage and so much worldly wealth are exploited and bullied by those very people whose ancestors benefited so much from the early Mesopotamian culture.

View from the top looking across the mountain-tops towards Iran. The smaller of the two optical telescopes with a mirror of 1.25m is in the foreground. One can see the Astronomers houses in the background through the mast framing the extreme right of the photo. The houses are at the junction of the red and white members of the mast. Looking along a line from the houses to the base of the observatory dome one can see the sheer cliff edge near the bend in the road. No place for small boys playing football.

Photo courtesy of Renas Ismael.