Chapter Thirty

Erbil to Sulaymaniyah Back Road

I travelled the Erbil to Sulaymaniyah back road at least once a week. Exiting Erbil we passed a large mosque in the course of construction. I was intrigued by the building methods, as bamboo scaffolding was used in the construction even to the top of the very high minarets. In fact, bamboo scaffolding has greater tensile strength than steel and the bamboos are bound together with jute string. Bamboo scaffolding is used extensively in the Far East notably China and Hong Kong.

On enquiry I discovered that the mosque was a gift to the city from Jalil Khayat ( Celil Xeyat in Kurdish) a millionaire uncle of Ava, one of our Kurdish clerical workers. Her uncle was a businessman who amassed a vast fortune from a humble beginning. He started a garment factory in 1927 and gradually built up a vast industrial and constructional international conglomerate. With his four sons he utilized the construction sector of his vast empire to build what is now called the Great Mosque of Hawler (Kurdish for Erbil) as a 20th Century gift to the city. He died in 2005 and his sons completed the Mosque. He was laid to rest in a mausoleum in the left side of the mosque. As the mosque donor was an uncle of one of my clerical officers, I had a greater than normal interest in the construction progress of the structure each time I passed it.

Jalil Khayyat Mosque.

Photo source: Faris Orfali.

The hospitals in Iraq were huge by any standards and when we travelled out of Erbil we passed Rizgari Hospital with queues of women in their black chadors waiting at the outside gate for admittance to visit. The huge 493-bed Rizgari Teaching Hospital was opened in 1984 presumably in the early heady Ba’ath Party days when Iraq was fired with socialist zeal. However, facilities there in my time were poor and sanctions affected them badly. Elderly family members of my staff had to be taken by car to Baghdad (400 km) to be operated on by visiting Amman surgeons. They were then brought back home immediately after surgery by family car or taxi to recuperate as there was no air-conditioning in the hospital in Baghdad where the temperature was hovering around 500C. There was no electricity to refrigerate the drugs whose efficacy would be practically zero before they even reached the hospitals. In Baghdad I used to see compounds in the city hospitals full of medical equipment including operating tables stored outdoors and presumably for sale or scrap. I assume that lack of spare parts rendered them useless. Like Dennis Halliday who stated that he broke sanctions by smuggling in drugs for the children, who contracted leukaemia, from the depleted uranium munitions used by the Allies, I used to smuggle them in also. Each time I left Iraq I was given a list of drugs by the Kurdish staff to bring in with me on my return. I used a pharmacist near the Safeway supermarket in Amman to do my purchasing and where I got all my requirements without any prescriptions as these did not appear to be required in Amman for medicines. The drugs were usually for elderly relatives with heart or respiratory conditions. As the Allies had not fought in the north there were few or no children suffering from leukaemia there.

We passed a line of traders’ stalls on the outskirts of Erbil selling water, fruit, nuts and crisps, in fact, anything the traveller required for the journey. A long climb followed and eventually the road crested the hill and we faced down a long plain at the foot of the Zagros. As we entered the plain we passed some stone pillar boxes that announced themselves to be the now deserted HQ of the local Peshmerga commander. About 10 km outside Erbil we passed a village that seemed to be a large installation for training Peshmerga police. There was always a column of them marching and counter-marching as we passed through. These were brave men as Saddam was still in power and his agents were everywhere marking people for future retribution. One agent, one photograph and these men would be hunted down if ever Saddam regained Kurdistan. As I passed them I remembered an old Irish song (‘The Bold Fenian Men’) where an old lady recalls the night in her youth (circa 1860) when she saw young men drilling in the mountains:

Tis fifty long years since I saw the moon beaming

On strong manly forms and their eyes with hope gleaming.

And the penultimate verse went:

Some died on the glenside, some died near a stranger

And wise men have told us that their cause was a failure

They fought for old Ireland and they never feared danger

Glory O, Glory O, to the bold Fenian men.

The training school is now the local police station.

Just outside this village we had to cross a military bridge spanning a deep chasm between the rocks. It was a one-lane affair and we had to queue to get across. It always raised a metallic protest when we were rumbling across it and each time it was a relief to get to the other side.

We continued on the plain at the foot of the mountains and passed a number of destroyed transmission towers. One day we followed a track off this road towards the mountains. We discovered that a tower had collapsed and the 132,000 volt conductors crossing a track were not much more than six feet off the ground. This track was used daily by locals to access a village further in. They must have used a detour as the local electricity authority had done an emergency repair of the adjacent network and must have warned them. Nevertheless any child could reach the deadly conductors with a stick. Safety was very low in the list of priorities here. The main thrust was to keep whatever electricity was available flowing. After passing numerous minefields with their death’s head pennants and the UNOPS de-mining teams carefully going about their deathly business, we approached Kosanjak.

Kurdistan is the most mined place on earth.

Photo: Brian Yamamura.

As I mentioned in the last chapter mines were laid everywhere in Iraq, particularly in Kurdistan. These minefields were mapped carefully by Saddam’s army when they laid them down but his government refused to divulge the locations of the mines to the mine-clearing agency UNOPS.

As we neared Kosanjak we had to cross the de facto border between KDP and PUK territory. This entailed going through the military checkpoints of the KDP (Barzani) first, then a drive through about one kilometre of no-man’s land before encountering the PUK (Talabani) checkpoint. Each had their machinegun emplacements concealed among the rocks and pointing straight at us. Only once did I see the men manning these machineguns. This was when I travelled with the UN ambassador in his car with the UN pennant flying and a security detail of UNOCHI troops leading us and forming a rearguard behind us. As we passed about 20 Peshmerga rose from behind the concealing rocks, stood to rigid attention and saluted us. It was most impressive and brought home to me the suitability of the Kurdistan terrain for guerilla warfare.

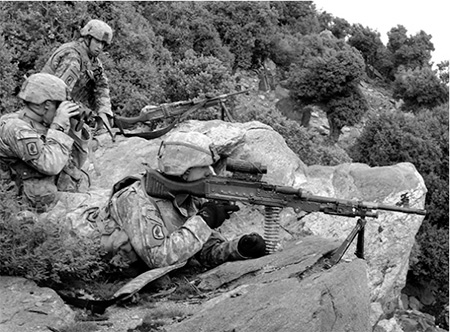

US troops using the same terrain to the same affect as the Kurdish Peshmergas during Task Force Viking the Invasion of North Iraq from Southern Turkey and the link-up with 70,000 Kurdish Peshmergas in 2003.

Photo: Sgt. Brandon Aird, U.S. DoD.

I was passing here another day and came across an historic event. It was quite some time after the Kurdish civil war and each side was returning their prisoners to the other side. The prisoners from each side had been driven to the rendezvous in buses and their relatives and friends waited for them in cars. The prisoners carried their pathetic belongings in paper parcels and were rushed by their families as they crossed the line. Both prisoners and their mothers in their black chawdors, cried as they embraced each other for the first time in years. Sadie Peres was prominent in the PUK welcoming group.

Eventually we entered Kosanjak via a long tree-lined road. There was a girls’ school nearby and it struck me that we always passed through there when the girls were going home. We seemed to go very slowly as the unmarried Kurdish drivers assessed the girls as future marriage prospects. We passed through the town with its statues of local heroes, in the primitive style, welcoming us. As we left Kosanjak we passed an Habitat housing project, the first large scale building scheme in the town for decades. We then climbed the corkscrew road up the pass that would take us into the heart of PUK territory. There was a PUK observation post on the summit where the view in both directions was incredible. It was while climbing this corkscrew road that Mountain One stopped me one day to warn me of snipers on the road ahead.

As we descended down the rock-strewn, fenceless road of the pass we came to a spot where the locals assured us that there was a strong magnetic ore in the mountain that pulled vehicles back up the gradient. They said there were only two such places in the world, the other being in California. We habitually stopped our transport here, shifted the gear into neutral and with our brakes off, but I was not convinced that we moved up the incline. There was a pleasant tea house at the base and it was most enjoyable to drink a cooling mineral in the leafy shade with a gurgling stream making restful music behind us. Further on we passed a sculpture of a young man from Scandinavia who had worked for an NGO and was killed at this spot. His parents had the sculpture erected in his memory, where it was still standing keeping a lonely vigil, far from his home and loved ones. I have been informed by my friend, Rojgar Hamid, that the sculpture has been removed and replaced by an underpass bridge. We passed numerous trucks stopped at the side of the road with their drivers kneeling nearby on their prayer mats and facing in the direction of Mecca. I was surprised to see them throw dust in their own faces and perform washing motions with the dust on their arms. I was told that this was part of the purification process during prayers. Normally this process would be carried out with water but because of its absence in the desert the faithful were allowed to use sand or dust instead which was, of course, in abundance in these arid landscapes. Another feature of this area, and particularly the area east of Sulaymaniyah, was the absence of pole transformers. These are normally like buckets on top of the poles to transform electricity from 11,000 volts to 220 volts for domestic use. The Peshmerga had removed them and sold them to Iran for their copper content.

Further we passed one of Saddam’s Russian Forts about five kilometres in from the road. It is called Suse Fort after a nearby village of that name and stands in front of Piramagroon Mountain.

Fort Suse reconverted cost effectively by US Army to a detention centre.

Photo source: US DOD.

These forts were built in the 1980s to barrack Iraqi forces as they tried to destroy the Kurds. It was used as a POW camp for Iranian prisoners during the Iran-Iraq war and then for Kurdish prisoners during the Anfal operations in the late 1980s. They were subjected to appalling cruelty and hundreds were killed within its walls. When Iranian troops were in this area their interrogators forced some of their prisoners to drink acid and endure an agonizing death. Since 2004 it has been used by the Americans to house 1,609 prisoners, some of whom took part in the insurgency, and others who were deemed to be international terrorists.

As we drove along we passed many rice paddies with the Kurdish families up to their knees in water as they cultivated their crops. We also noticed large groups of women in their gaily coloured dresses tilling the fields. These are the widows of men murdered and disappeared by Saddam who now hire themselves out to local farmers as they try to feed their children. They worked in the open, even on the hottest days in an area where the midday temperature can reach 500C. There are now between 900,000 and one million widows in Iraq as a whole. In my time an American worked in Erbil who was an international expert on poultry farming and appropriately enough was nicknamed ‘Mr Chicken’. He was very enthusiastic about his chosen profession and used to organize ‘Omelette’ breakfasts at the UN Club. Like the rest of us he was shocked at the plight of women in the area and initiated the poultry production project for the widows. A number of areas were called ‘cities of the widows’ where most of the men and older boys had been massacred; although I believe the first area so-called was the village of Barzan. Mr Chicken, of course, planned to provide poultry production facilities for these areas, a man called Clark, the then head of Habitat, was to provide the buildings and I was to look after the power. I grew very friendly with Clark and we used to meet in his office after work on Thursdays where we opened a bottle or two of beer. Clark had an Irish assistant, a young man from Skibbereen in County Cork who would form a threesome at these sessions. However ‘Mr Chicken and Mr Clark had to leave the area in a hurry when Saddam expelled all US and UK passport holders and the project had to be shelved. The women of the area had a true champion in Mountain One (Irene Massey of the 4R’s NGO), who ignored Saddam’s expulsion decree for UK passport holders to leave Iraq. Irene was a barrister and I witnessed some hard-bitten Kurdish warrior government ministers cringe and shift in their seats as she pressed the case for these heroic women.

Nearing Sulaymaniyah we passed Tazluja Cement Factory that was about 20 km from Sulymainiah and near a large communal well where 50 or 60 women were gathered in their colourful finery as they exchanged the local news while waiting their turn at the well. Tazluga is the area the snipers fired on a UN car minutes before I passed it. It was also the place I had in mind to set up a factory to produce concrete poles for the electricity networks. I had visited and seen these factories operating in Amman and the Jordanians were happy to sell one to us. It would have saved much UN money and resources to produce these heavy poles here rather than buying them abroad and transporting them to Kurdistan. It would also have provided employment to manufacture and transport them for the Kurds.

One Friday a convoy of us was returning to Erbil from Sulaymaniyah and we decided to have a picnic to break the journey. Eventually the drivers turned right and we were on our way into the mountains. We continued on a road that got narrower and narrower as we went along and finally stopped when it had turned into a practically impassable track. The whole area was impressive as the mountains soared upwards as bare rock bereft of cover or foliage. I was told that this was Kore where the Iraqi Army had driven the Kurdish Peshmerga and where the Kurds decided to make their last stand. The Iraqi Army, the fourth largest in the world, was held and did not prevail. They were pushed back and when they tried to regroup the No Fly Zone was established. Saddam’s army retreated and Kurdistan was free.

The area was in the eastern side of Rowanduz, a place sacred to Kurds. They frequently met the forces of Saddam here and the fight was usually to the finish. It brought to mind Leonidas and his Spartans at Thermopylae. It is the Kurdish GPO (General Post Office, Dublin where Irish Patriots made the Blood Sacrifice in 1916 and galvanized the people to make the final and successful fight for freedom in 1920/21). It also brought to mind the Statue of the Dying Cu Chulainn by Oliver Sheppard in the GPO, Dublin, commemorating the 1916 rising. In early Celtic times Cu Chulainn defended the gate to the North (Ulster) and though mortally wounded tied himself to a stone pillar so that he could continue to face his enemies even in death. When a raven lighted on his shoulder and plucked at his eyes his enemies knew he was dead and only then had the courage to approach him.

On this picnic we were escorted by some of the Sulaymaniyah UN staff as far as the picnic site. They were led by the UN Field Delegate and Area Security Co-ordinator for UNOCHI in Sulaymaniyah, Siddarth Chatterjee, who had been posted there from Baghdad and with whom I became quite friendly. Siddarth is an Old Wykehamist, having been educated in Winchester Public School in England. He came from a prominent Indian legal family and joined the Indian Army. Murthy told me that he quickly went up the promotion ladder and was posted to the Indian Special Forces. He was wounded twice and was decorated but on the third occasion he was so badly wounded that he was told he was out of the running to command the Special Forces. To command this regiment had long been his ambition and when he learned that it was not now achievable send in his resignation from the army. He was offered command of any other regiment he chose but rejected the offer and joined the UN. He was very helpful to me when we had serious trouble with the Sulaymaniyah authorities and offered unstinting advice and support. In the UN club in Sulaymaniyah he introduced me to Malibu and orange on the rocks, and whenever I see Malibu I think of Siddarth. When he left Iraq he was posted to UNICEF in Kenya, and later to Somalia. He married the youngest daughter of the Secretary General of the United Nations, Ban Ki-moon, Ban Hyun-hee when they both worked for UNICEF at their office in Nairobi, Kenya. When Staffan de Mistura was appointed UN Special Representative in Iraq in 2007 he chose Siddarth as his chief of staff. They had both worked in Iraq during the First Gulf War and Siddarth had made a very positive impression on Staffan.

Boys will be boys: Roger Guarda, left, our UNDP director and Mousa Olayan our Admin. Officer, kick a football around at our picnic near Kore Rawanduz. Note the decaying mountain in the background.

Also at the picnic was my friend, Irene Massey. We hit it off straight away when we first met. She was Head of the 4R’s organization in Kurdistan. This was an NGO (Non Governmental Organization) that looked after women’s interests and welfare in the north. She took over from one of her brothers who had been declared persona non grata by Saddam for getting Kurds out of Iraq without proper documentation. She was a very vivacious lady who had been married a few times. One of her husbands had been an Irishman called Massey. This is a name common to Macroom in County Cork where they have a mountain named Mount Massey. Irene told me that one of her marriages lasted five hours; I am unsure if it was her marriage to Massey. I managed to have a great rapport with her as I have four daughters and was anxious at the plight of all the Kurdish war widows trying to support families without governmental assistance of any kind. I had a great respect for her as she was a woman of tremendous energy and ability. She was a Barrister of the High Court Circuit in London and the south of England. Her Ankawa office was halfway between the Habitat office where the boss was an Englishman named Clarke and the UNDP office and we often formed a group in the UN club. One day we were talking of our backgrounds and I must have taken too much of the cup that cheers because I boasted of my connection with the Irish liberator, Daniel O’Connell, and recounted that at one time he was known as the King of the Beggars and that Jules Verne had a painting of O’Connell in Captain Nemo’s cabin in the book Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Incidentally this reference was omitted from the early translations of the book published in Britain for fear of offending British sensibilities. Irene put me in my place by mentioning that she was the only daughter of the Queen of the Ashanti in Ghana. This is a Matrilineal Monarchy and Irene will be the next Queen. There are about seven million in the tribe and one of the UN staffers confirmed that when he visited Ghana with one of her brothers, some of the locals came to meet them and an old man knelt in front of Irene’s brother and placed the brother’s foot on his head. She attended a Catholic Convent in Ghana and went to University where Conor Cruise O’Brien was President. She was head of the Students’ Council and crossed swords with him a number of times. She got some satisfaction, however, when at state functions she was ahead of Conor in precedence because of her position in her tribe. As far as I am aware things have changed now in Ghana and people regard themselves more as Ghanaians rather than from any tribe. From her brother’s time the 4R’s had the radio call sign Mountain so Irene was known as Mountain One. My call sign was Power One and whenever my convoy would approach a city with Irene in residence the radio would resonate to the call “Mountain One, Mountain One, come in please Power One, over,” to my intense embarrassment and the comments from the rest of the convoy. She was mischievous too and staged a number of embarrassing photos of us both together that were posted in the glass frame of the UN club Erbil for many years after my departure.

One afternoon during the period when there was a reputed $5,000 reward for the heads of UN personnel I was going from Erbil to Sulaymaniyah and my car was climbing up the pass after Kosanjak when a convoy passed us on their way down. A few minutes later as we noisily climbed I spotted some cars behind us, blowing their horns and flashing their lights. They were obviously trying to stop us. We thought that they intended to do us mischief and claim their $5,000. Naturally we were unarmed and I told the driver to put the boot down. However, they caught up with us and Irene stepped out. She told me that a UN staffer had been fired on down the road near Sulaymaniyah by the cement factory at Tasluga. The bullet had gone through the glass on the door behind the driver; she advised us to turn back. I figured that the gunmen weren’t up to much at the sniping game when they couldn’t allow for the lateral movement of the car’s speed. I felt that the Sulaymaniyah Peshmergas must have dealt with them by then and I elected to carry on. Thinking back on it, it was a stupid decision as the gunmen could have repositioned themselves at another point off the road. I not only put myself in danger but my Kurdish driver also.

Another stupid action on my part was when US planes were attacking Iraqi Army units north of Mosul, prior to Bill Clinton’s December 1998 bombing. The US planes were operating from Incirlik Air Base in Turkey and we could hear them but not see them passing over. We were warned to keep away from the Erbil to Mosul road in the afternoons between 3 and 5 o’clock. I was anxious to see the planes from a distance as they strafed the Iraqi positions and drove out during the forbidden hours. Again it never dawned on me that I was putting my driver’s life in danger as well as my own. In fact, the American planes attacked and killed a number of young shepherds as they guarded their flocks. Needless to say I never witnessed any action. The Iraqis retaliated with Scud missiles and other SAMs. Again it was an unequal but dangerous contest. One of the Iraqi Scud missiles landed in the grounds of the huge Regional Hospital in Dohuk. Finally, we got through the last PUK checkpoint and joined the Sulaymaniyah-Kirkuk road and we were in the suburbs of Sulaymaniyah. We passed the massive grain silos that seem to dominate all Kurdish cities, and proclaim them as the bread baskets of Iraq, and we were on Selim Street, the main street of Sulaymaniyah.