Chapter Thirty Seven

Mission to Bosnia

Our next destination was Sarajevo and we were a bit apprehensive as our plane slid down to the ground through the dangerous looking mountains surrounding the airfield. We had to make a wide detour to the west as the Serbian-Kosovo conflict was in progress and the NATO bombing campaign was imminent so the airspace in the area was dangerous. In fact the bombing started on 24th March. The flight controllers were from the Italian military, as all the civil air navigation facilities were destroyed during the siege of the city by the Serbs. Later when I worked in Sarajevo this situation still prevailed and when I was due to use the airport it was a matter of the weather being kind enough to let me fly as the military facilities were not up to civilian requirements if the weather deteriorated.

Sarajevo Airport, nestling between the mountains. At the time it was a very dangerous place to land.

Photo: FaceOffic, www.wikipedia.org

When we landed we were ushered in through the destroyed terminal building and the formalities were over quickly when we produced our UN documents. The place was largely bereft of glass in the windows and not at all pleasant as we waited in -100C for our baggage. As a matter of fact the US Army had to install a Fire Finder Radar System, on April 20th 1996 to counter Serbian attacks. The Fire Finder Radar has the capability to determine where a round was fired from, where it will land and will compute co-ordinates for a counterattack if needed. I thought that they could at least have replaced the window glass.

It was early March and the temperature was well below zero with the winter snow still on the ground. It was quite a difference to India. We hoped to interview some engineers from a local consultancy company, Energoinvest, that specialized in tower construction and international consultancy especially in North and Central Africa. I had previously seen examples of their work in Zambia. All of our Australian/Bosnian engineers had worked for Energoinvest. One of the first objects one would encounter on the way in from Sarajevo Airport along Sniper Alley was the huge Energoinvest Tower Testing Gantries where entire assembled towers are tested to destruction by subjecting them to enormous tension, compression and torsion forces. This was a laborious process as the actual design of the towers is quite complex and is now done by computer. The design computer has facilities that take account of all conditions including the deformation of the slender steel tower members during the galvanizing process. Nowadays the whole testing process is computerized using sensors that measure tension, compression torsion and deflection.

The Energoinvest Tower Testing Gantries.

Photo source: Comdt Damien Coakley, Irish Defence Forces.

On our right going towards the city and still on Sniper Alley we saw the ruins of the building of the Sarajevo newspaper Oslobodenje that featured in the film Welcome to Sarajevo. Its 10 storeys were destroyed by the Serbs but the paper continued production from a makeshift office throughout the entire siege that turned out to be the longest siege in modern warfare. It lasted from April 5th 1992 to February 29th 1996. Later there was some discussion among the Sarajevo City Fathers to leave the ruins of the newspaper building as they were to act as a siege memorial. However, commerce dictated otherwise. Someone bought the ruin, pulled it down and erected the ultra modern Avaz Business Centre in its place.

As we approached the Old Quarter of the city we passed the destroyed Tito Cadet Barracks on our left. When I worked in Sarajevo some time later I was a frequent visitor to the barrack as the de-mining agency was located there. I believe the barracks is now part of Sarajevo University.

Sarajevo was famous for its draught beer and I took the odd libation. My son visited me there and I took him around to some of my watering holes. However, when he came out to Sarajevo with the Irish army, he was appointed Deputy Security Officer for Bosnia and promptly closed down a number of my favourite hostelries, as they had Mafia connections. I used to frequent three in particular. One was ‘The Dubliner’ a cellar bar in the Old Quarter. For me the draw was the enormous bowl of salted peanuts served there with each drink. It was obviously Mafia as a young man was killed outside its door one night. It was one of the ones my son closed down. Another club I frequented was the University club that had huge bars on each of its three floors and almost by definition was very noisy. I found the third when I worked in Sarajevo some time later and roamed around its bombed-out buildings. It reminded me of Kiev where I used go under an arch leading into gardens where the main entrances to many of the houses on Artioma Street were located. In Sarajevo I used to go into the derelict area behind the bombed out houses. In one of them was a door leading down to a basement that turned out to be a very atmospheric bar. I was thrilled to hear that U2 patronised the place and performed in the tiny bar during the period of their famous concert in the city. It brought back memories of films of spy thrillers in Berlin after WW2.

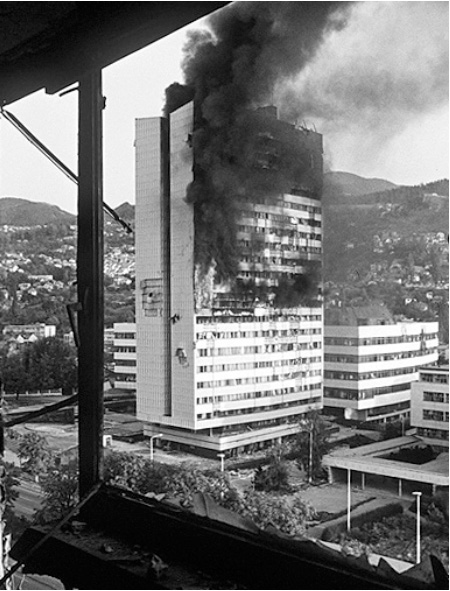

The Parliament Building Sarajevo burning after Serbian tank shell-fire during the siege in 1992.

Photo source: Mikhail Evstafiev.

The restored Parliament Building in 2010.

Photo source: Comdt Damien Coakley Irish Defence Forces.

We next passed the destroyed Parliament Building, a sorry sight with most of its windows blown out. This was a result of the three-year siege by the Serbs. The building was not as damaged as similar buildings in Baghdad and Belgrade that had been subjected to Smart bombs. The Smart bomb buildings there would have to be pulled down. In Sarajevo the Bosnians were able to restore their Parliament Building and Chamber of Deputies building in a few years. There was a pair of twin high rise buildings that were also badly damaged and the Bosnians tried to restore one by utilizing undamaged material from the second.

One night as I was walking down Marsala Tita Street I saw a military personnel carrier flying what I thought was the Irish flag. I shouted and ran after it catching it at the traffic lights. I waved in the window to discover they were Italians. The flags of both countries are almost identical. I was a lucky man as my running after the military vehicle could be misinterpreted and a nervous Italian could have made me a statistic. My family says I am not fit to be let out on my own and in this case they are right.

We made a point of visiting Adnan Sehovic’s sister when we were in the city and met her at her house near the Franciscan church. Adnan, who was on vacation at the time, joined us. While there I heard some amazing stories of what the ordinary people endured during the long siege. I went to the Catholic Cathedral in Sarajevo that evening and received Holy Communion from Cardinal Vinko Puljić there while Adnan and Mousa both Muslims looked on from the door.

The Cathedral of Jesus Heart in Sarajevo. It is one of the main symbols of the city. Its twin towers feature on its flag and seal. I was proud when I heard an Irish soldier from Cork do the Sunday Mass readings on one of my visits.

Photo source: Domenico Feminò.

We held our interviews in the offices of Energoinvest and recruited 10 Bosnian engineers for Kurdistan. Afterwards we visited the famous Energoinvest Tower Testing Gantries and then the Energoinvest Steelyard where we were shown tons of galvanized steelwork reserved for Iraq. Our hosts informed us that these had been ordered by Iraq before the imposition of sanctions and were now in limbo in Sarajevo until sanctions would be lifted. Here were we, ordering new steelwork on behalf of the UN, and in Sarajevo was similar steel ordered by Iraq and manufactured for them that had to remain in Sarajevo, because the sanctions of the very same UN had ordained they be frozen there.

On my return to Erbil I laid out a new organizational chart. I decided to build teams from the larger consultancy companies that had contracted engineers to the programme and stationed them in separate governorates. Thus I put a team from TATA in India under one of their chief engineers Dr Vinni, who was due to join us, in Dohuk, a team from Bosnia under Izet Vejzagic, a senior engineer from Energoinvest of Sarajevo, in Erbil and a team from Australia (SMEC and HECEC) under John Casey in Sulaymaniyah and I fostered a certain amount of rivalry between them. There is a strong engineering tradition in Bosnia notably in High Voltage Transmission Lines and in tunnelling arising from their experience of building roads through their incredibly difficult mountain terrain. I had previously come in contact with some of their work particularly what was locally called the Tito High Voltage Transmission line in Zambia. This line was 99% built but never completed due to political circumstances. Later on I had ample experience of their tunneling capabilities when I worked in Serbia and Bosnia. Indeed the SMEC team contained some Bosnians who had immigrated to Australia some time previously. This policy ensured that the engineers with the greatest experience of dams and hydropower stations i.e. those from Australia were located in Sulaymaniyah the governorate that was home to both Dokan and Derbendikhan.