Chapter Thirty Eight

End of my time in Saddam’s Iraq

I returned to Erbil and felt I was coming home as we swept into the darkened city and passed the sentries at the main intersections, as they sat on the roadside kerb, warming their hands from the heat of little fires burning in the gutters. We passed the area of the displaced persons as they tried to eke out warmth and shelter for themselves in the ruins of an extensive and totally destroyed Iraqi military barracks. We finally reached Ankawa and entered within its ring of Peshmerga checkpoints and felt safe.

Around this time I had problems with my blood pressure and attended the Polish Army doctor who was with the UNOCHI guards in Erbil. Obviously my bachelor lifestyle did not help. The doctor happened to be a cardiologist and treated me with the most up-to-date drugs but warned me that the hot climate was not doing me any good and that I should return to more temperate climes. I informed Roger of the doctor’s comments and said that I would not renew my present contract in July. He suggested my wife and I should live and work in Amman and commute to Iraq every few weeks. I reckoned that it would take a day to go to Baghdad, a day in Baghdad and on to Kurdistan, three days travelling in Kurdistan and three days working there. The return journey would take a further two days, making each tour last a punishing 10 days. This desert travel was quite risky. On one of my last trips I travelled with my hand resting by the open widow of the car and had to withdraw it when the back of my hand began to hurt. A few months later, at home, a cyst had to be removed from the hand and when the biopsy reports came back it turned out that the cyst was pre-cancerous.

However, I had second thoughts about staying on. We could not improve the situation without more generation and we were precluded from doing this by the sanctions regime. The hydro generating stations were now safe but the capacity had not increased. They were still producing 300 MVA instead of their rated output of 649 MVA. In fact this has not yet been achieved 12 years later in spite of all the finance and technical expertise available since 2003. The sanctions were to force Saddam to comply with UN directives by slowly strangling the Iraqi people and their children and forcing them to oust Saddam. Anyone who had the slightest knowledge of what was happening in Iraq knew that this was pure fantasy. It has failed the largest army in the world to adequately deal with the Sunni insurgency since 2003. So what chance was there for the Shia, the Kurds or any disaffected army officers of achieving change? Moreover the autonomous area in the North (Kurdistan) was removed out of Saddam’s orbit. In fact, he loathed them, so increasing their electricity generation would not improve Saddam’s infrastructure. I felt that the UN was inflicting a war crime on my adopted people and that I was part of it. I determined that I would resign as I could not draw a salary from the trough of the Kurds and Iraqi peoples’ agony. It was a time of change in Erbil and with it the intrigues this brought on. A chance soon manifested itself and I tendered my resignation. Kurdistan was threatened by drought in early 1999 as the snow run-off into the reservoirs that spring was not as high as usual. The electricity output of the two dams was therefore threatened and we were asked to formulate a plan to meet this new crisis.

Off-loading one of the 353KVA diesel generator sets for the water pumping emergency.

Photo: By kind permission of Mousa Olyan, UN.

I decided that the best option was to install a large number of 500 KVA generating sets in strategic areas. When drought had passed and the hydro-electric stations were repaired, the generating capacity was thereby increased. The mobile generators could be relocated out to new sites that did not have electricity at all since the1980s and the area with some type of electricity would increase. As our bigger 29 MVA generators would come on stream the mobile generators could be moved out again to gradually increase the electrical coverage. I discussed this idea with John Casey who agreed with it and then put the proposal to Roger. I knew previously from Roger that the UN had stored hundreds of diesel generators of roughly this size against the day when they would be required in emergency disaster areas. Before one could blink Roger had acted and booked hundreds of generators. However, I note from the ENRP Fact sheet issued soon after I left Iraq that 377 small diesel generators intended mainly to supply water pumping stations in face of the drought were to be installed between July 1999 and January 2000. They increased the electricity output for the area by 32 MW (megawatts). Eventually the UN provided more than 2,000 small to medium size generators to deliver emergency supply to essential humanitarian facilities such as water pumping stations and hospitals.

We purchased a number of mobile substations for emergency locations. Indeed, strange to say, one of them went missing and we had trouble locating it. I had Denis Johnstone beavering away on the contract documents and specification for the 29 MVA (Mega Volt Amperes) Diesel Power Plants. These went to tender at the end of 1999 so I was quite satisfied that we had done all that was possible with the resources available to us and the constraints under which we operated.

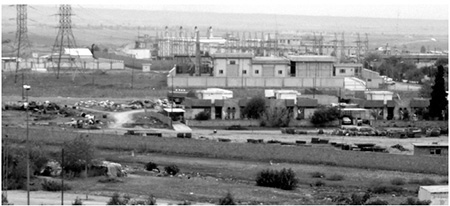

The 29MVA Generating Station and Transmission Sub-Station in Erbil. The four chimneys can be seen slightly to the left of centre of picture.

Photo source: WC Spiller.

I was quite satisfied with what I had achieved. I had changed the entire modus operandi and laid the groundwork for changing the implementing agency from UNDESA to UNDP as well as moving the procurement operation from New York to Amman. As the time for my departure drew near the Kurds approached me many times and asked me to change my mind but I had crossed the Rubicon. I made my peace with the few people I crossed swords with, there were two. I visited all the UN offices and bade adieu to every one of the staff and took their photos as keepsakes. Kuistan and Miran hosted a meal for me as did Farhad Putrus my driver friend.

I spent my last night in Erbil in the garden of the UNOCHI complex where all the UNDP staff hosted a farewell meal and dance. My heart was heavy as I spoke to each of them in the balmy fragrant garden and was presented with a number of gifts that now grace my home. A local photographer was on hand to take photos and to record the occasion on video. As I left the garden, Hassan and a number of ragamuffins, the local Baker Street Irregulars, trotted behind me each bearing one of the gifts I had been presented with. On the following morning the entire staff of UNDP waited outside the office as Mohammed Al-Khaldi, one of the Baghdad drivers, arrived to take me away. My eyes were wet as the car drove away from Ankawa as I began the long journey home.

Since my departure Kurdistan has progressed by leaps and bounds and it now aspires to rival Dubai as a showcase of the Middle East. I am also glad that Kurdistan has stood out as a beacon in a troubled area of a troubled world. It is now a sanctuary for persecuted Christians and a place where women can aspire to and achieve equality with their brothers.

There are some people that one comes in contact with on our journey through life that make one feel better for having known them. I met more than my share of them in Iraq. In Baghdad Imad Hannoudi, Imad Khadduri, Jessica Eliasson, Dr Ayad Humanaide and Mohammed Al-Khaldi stand out. In Kurdistan Farhad my driver, Farhad Al Mulla, Azziz, Hojar Shalli and Mousa my friend spring to mind together with Vianne, Kuistan and Kajhal and, of course, the two Humanitarian Co-ordinators Dennis Halliday and Hans Von Sponeck. Dennis and Hans were moral giants with the integrity and sense of honour of medieval knights. They shed great lustre on both their native countries and on everyone’s perception of what the United Nations should be.

In August 1997, Dennis Halliday was appointed the UN’s Humanitarian Co-ordinator in Iraq. He was not long in the position when he began to champion the cause of the children of Iraq. He claimed that four to five thousand children were dying unnecessarily every month due to the impact of sanctions. He felt that he was caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand he was a representative of the United Nations that was responsible for the sanctions and the arms inspections and on the other he was responsible for directing the huge humanitarian aid programme, the Oil for Food programme that was designed to mitigate the effects of the sanctions.

The programme was totally inadequate and within a few months of taking over he was instrumental in having the oil money increased from $2 billion to $5.35 billion every six months. Dennis felt that the whole process was a complete breach of the Convention of the Rights of the Child, of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the very charter of the United Nations itself. He could not in conscience be part of this UN process and resigned from the post in Iraq and from the United Nations as a whole effective 31st October 1998 after serving the Organisation since mid 1964; some 34 years. In the furore that followed his resignation he felt free to air his views and became a prominent speaker on the subject. He was a fervent anti-war advocate and fearlessly championed the cause of the Iraqi people and their children. Every meeting we had with him concerned the health of the people and the lack of drugs for them. Drugs were useless without refrigeration and without electricity there was no refrigeration. He went into great detail on the calorific value of the monthly food allowance for adults, children and pregnant women and he constantly signalled the ethnic cleansing being carried out by the Saddam regime.

He had estimated that the number of children who died as a result of sanctions was close to 600,000 based on a UNICEF figure of 500,000 for a few years previously. Including adults, he estimated that the number of Iraqis who died reached 1,000,000. The causes for these horrendous figures were obvious to all of us who worked there. This was the deliberate destruction by the allies of the strategic infrastructure of the country. The water, sewage, transport, communications, electricity, educational and industrial systems were in tatters. It was a country where disease thrived and was manifesting itself in the mortality figures. Typhus and cholera were widespread and leukaemia caused by the depleted uranium munitions used by the allies. The UN and the US overlooked the fact that 90% of Iraqis wanted to raise their families in peace and with the expectations that everyone has for their childrens’ future. Like the guards at the Nazi concentration camps, who had loving family relationships in their own homes, within kilometres of the camps where they perpetrated the most appalling atrocities on the inmates, the people of the outside world shut their minds to the suffering children of Iraq. But then, of course, they had demonised Saddam Hussein and it was easy to extend the demonisation to the Iraqi people. Once this process is reached where the victims are regarded as almost subhuman it is so easy for genocide to follow albeit it is slow and callously clinical. This process was designed to goad the Iraqi people to rise in rebellion against Saddam. It was a form of warfare not against Saddam who survived quite well but against the ordinary people. And the wonder of it was that the Allies were surprised when the majority of Iraqis did not greet them with open arms. The Iraqis did not see them as liberators but as the power that imposed sanctions on their country. The Allies also forgot the concept of patriotism. They forgot the folk memory of the Crusaders, Salahdin and the Eagle of Salahdin.

Dennis was also very concerned that the UN was reluctant to finance the rehabilitation of the country’s infrastructure and that the UN absolutely rejected the concept of reconstruction. He also objected to delays in the Security Council’s sanctions committee and problems UN agencies encountered in procuring supplies. This only reinforces the concept of the two UNs, those in New York and those at the coalface. All of us wholeheartedly supported Dennis and his views. We were all singing from the same hymn sheet.

Hans Graf von Sponeck.

After the departure of Dennis Halliday the Secretary General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan appointed Hans Christof Graf Von Sponeck to succeed him. Hans Von Sponeck took up the position in October 1998. A married man with three children he has degrees from the University of Tubingen and the University of Bonn in modern European History and from the Louisiana State University and Washington State University in Anthropology and Sociology. It is said that he was the first conscientious objector in post-war Germany.

His UN background was very similar to Dennis’s. He joined the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 1968 and climbed the career ladder until he was appointed to Baghdad in 1998 and took control of 500 international and 1,000 national staff there. Whereas I met Dennis many times in Baghdad and Kurdistan I met Von Sponeck on a few occasions only. He came to Kurdistan after the killing of a UN staff member in Erbil near Ankawa and he visited the Wartsilla diesel generating plant shortly after it came on-stream. I had to prepare a briefing paper for him on the state and progress of the electricity sector. He came across as a measured unflappable man with an aristocratic bearing. His enunciation of English was again very measured with crystalline clarity. I met him again in the Canal Hotel in December when Roger, Mousa and I made our dash down through Iraq during the Clinton bombing. He was looking after some UN ladies who were terrified at the shock and awe aspect of the devastation. We had lunch with him before we organized the convoy of departing UN international staff to Amman. The fact that he was one of the few left behind did not faze him in any way.

Due to events in Amman with the border closed due to the return of King Hussein from hospital I did not get back to Kurdistan until mid-January 1999 and was astounded to learn that Hans resigned shortly after on February 13th in protest at the Sanctions and the Oil for Food Programme. On the following day, Jutta Burghardt, head of the World Food Programme (WFP) in Iraq, also resigned her post. The resignations of these principled UN managers coming as they did on the heels of Dennis Halliday’s resignation caused an international sensation. They dealt the callous policies of the UN and their clinically detached execution a blow that denied them the respect of all righteous people.

To sum up Dennis’s position I quote him: “The loss of life inflicted on ordinary Iraqis by the sanctions is incompatible with the United Nations Charter. The continuation of these sanctions in full knowledge of their deadly consequences constitutes genocide.”

Hans von Sponeck’s statement upon his resignation sums up his position: “I’m not at all alone in my view that we have reached a point where it is no longer acceptable that we are keeping our mouths shut.” My position on the matter is that I am proud to have played on the same team as Dennis, Hans and Jutta and to the same rules.