Chapter Thirty Nine

Basra Army Base

After the fall of Saddam I was invited to return to Iraq, this time to Basra to help in the rehabilitation of the electricity grid in the southern Governorates where the British Army was located. The network there was strategic to the world economy as it served the oilfields of southern Iraq. It was also the scene of the major battles between the Allies and Saddam’s Forces when the transmission system was destroyed almost beyond repair. Basra International Airport was the HQ of the British Army in Iraq and home to 5,000 British troops. I had mixed feelings before I decided to accept the invitation. Generations of my countrymen and women had suffered at the hands of the said army and had to endure the Famine and the Irish Diaspora as a result. On the other side I was thrilled at the opportunity of returning to Iraq and the experience of living in the main base of a great army at war and witnessing its incoming supplies and impedimenta through the airport.

There were a number of entry methods and I used two of them during my time there. One was via Bahrain then by air across the desert to Basra. The second was via Kuwait then along the Highway of Death to the Iraqi border where I was met by a convoy of British Army troops who escorted me safely to their base at the International Airport at Basra. My first entry route was via Bahrain. I arrived at King Fahd International Airport and had to stay for a few nights in Manama the capital of Bahrain before I could get my connecting flight to Basra. I utilized my waiting time by hiring a taxi and went on a sightseeing tour of the city. My driver certainly entertained me with his views on homosexuality that he considered much superior to the heterosexual variety. To my surprise he told me he was married with a grown-up family but emphasized the necessity of beating his wife frequently to let her know who was boss. I was a wee bit apprehensive when we stopped at any isolated spot. I knew that I could deal with him on a man to man basis but I was unsure what he had concealed under his long white thawb. I was much taken when I passed a Bahraini ocean-going dhow or baghlah that brought back romantic pictures of Sinbad and his voyages. My guide took me around the city and showed me many of the ministries buildings and my objective of the following day, the US Fifth Fleet Navy Air Base.

He then took me out on the 15-mile King Fahd Causeway that links Bahrain to Saudi Arabia via the island of Umm an Nasan. About 18 million people transit it annually, many of them Saudi weekenders anxious to celebrate in Bahrain where alcohol was available.

A terrestrial view of the King Fahd Causeway looking east to Bahrain, taken from the midway tower Restaurant.

My driver took me to the restaurant on top of the tower on the island of Umm an Nasan where I was able to take great photos of the causeway. The restaurant was not in operation but the hospitable manager gave me a free run of the place.

We next went to the Qal’at al-Bahrain. This is a fort with artifacts going back to 2,300 BC and was occupied up to the late 1700s in turn by the successive civilizations that dominated the area. With a sense of relief I paid off my taxi driver and ignored his attempts to have me engage him the following day.

The next morning another taxi arrived at my hotel to take me to the US Navy Fifth Fleet Air Base. On entering the base I was directed to a hut used by the RAF. It was the first time I came in contact with serving members of the British crown forces and as a result of an extreme Irish Republican upbringing I made myself as inconspicuous as possible. There were some travellers there before me and a few more drifted in after me. When our full complement had arrived we were taken to our waiting plane. To my surprise it was an old decrepit DC 3 on charter. We were not long in the air when a gentleman acting as steward announced that we were to touch down at what sounded like Dar as Salam. I was surprised as I thought that this city was down in East Africa. It was some time later that I discovered that we were heading for Ali-al-Salem. This was a Kuwaiti air base some 23 miles from the Iraqi border and was then occupied by a squadron of RAF with their twin engine, variable swept back wing Tornado fighters.

When the Iraqi Army captured the base in 1990 they hung the Kuwaiti commanding general off the base flagpole and shot all the other Kuwaiti servicemen on the base.

The base had a number of HAS (Hardened Aircraft Shelters) built by the French who assured the Kuwaitis that they were bombproof, impenetrable, aircraft shelters. However, the HAS were destroyed in the First Gulf war in 1991 (Operation Desert Storm). When the Allies’ ‘bunker busters’ destroyed them the Kuwaitis took the French to court.

As we approached the isolated desert base it brought memories of Biggles of my childhood books to mind straight away. We landed at a very steep line of descent designed to minimize our exposure to SAMs (Surface to Air Missiles) from Iraqi insurgents. We deposited our cargo and took off immediately for Basra where we landed with the same steep descent.

The sentries guarding the main entrance to the terminal building.

I went straight to the terminal building that had, naturally enough, a Middle Eastern façade reminiscent of Saddam’s palaces in Baghdad. I entered the main terminal entrance that was guarded by two soldiers; one of them was wearing the red-over-white hackle of the Royal Regiment of Fusilliers. The Northumberland Fusilliers took the white plumes of the French soldiers they killed in St Lucia in 1778 and dipped them in French blood, hence the red-over-white hackle.

I went through the security procedures in the Arrivals Hall of the airport. I was then directed to the office I was assigned. In the early days after the war all the work took place in the first floor of the terminal building that also housed the canteen, the sleeping quarters of the Staff Officers and the Civilian Engineering Consultants and even the officer’s mess.

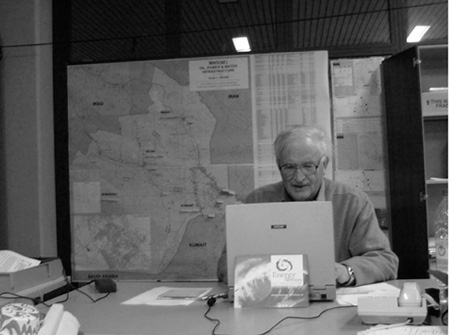

The Author at work in Basra International Airport.

My office was very large and all the consultants fitted in quite comfortably. In fact, one of them was a Glasgow Rangers supporter who regularly played football around the desks and woe betide anyone who got in the way of one of his strikes at one of his imaginary goals.

Our sleeping quarters were in a windowless room down the corridor that accommodated about a dozen consultants in two-tier bunks. The Staff Officers also had their quarters along these corridors and I saw many Irish names on their doors. I suffered from sleep apnea and was soon targeted as the champion snorer of the room. My title was recognized when the previous champion presented me with a few boxes of Snoreze tablets, he was handing his crown over to a very worthy successor.

The toilet facilities consisted of a long line of chemical toilets strung along a line at the edge of the airport apron. To go there in the middle of the night was a nerve-wracking business as one would have to traverse down three flights of stairs with one of those torches that were attached to the head like miners lamps and then go across a very exposed space to reach them. They were unisex and were equipped with gel dispensers in lieu of washing facilities.

As there were few reasons for leaving the building, in no time we suffered from cabin fever. Being in a war zone we were limited to ‘two and no more’ in the officers’ mess so our lifestyle tended to the monastic. One comfortable aspect of the base was the home television channels that we viewed on a large screen on a balcony. I smiled when the winter sales of Clerys, a Dublin department store, were featured regularly on the commercial ads.

A number of incidents stick out in my memory arising my time at the base. The first occurred early on in my time there. This was the celebration of Robbie Burns night on 25th January by the Scots Regiment then rotating through Basra. All the officers, dressed in their tartans and kilts or trews, sat down to dinner. The shrill notes of the bagpipes sounded as the piper escorted the haggis into the room. I’ll never forget the fierce intensity on the faces of the young men as they enacted their annual ritual. The second incident occurred at the end of one of my missions there when I was enjoying a few drinks with Malcolm Holmes, the project manager for Scott MacDonalds, a major Scottish consultancy company. The talk turned to the supernatural and Malcolm recounted the following story.

‘A few years ago I was working in Doha on the Gulf. One evening I was reading the paper in my house as I waited for my wife to finish her preparations for dinner. My two daughters were playing in a corner of the room. Suddenly a candlestick rose from the table in front of me, glided through the air and deposited itself down at the far end of the table. I was incredulous “did you see that?” I asked my wife, “I did she said. ” From then on similar unexplained incidents occurred culminating in the materialization of a young girl dressed in medieval costume. She became a familiar presence in the house and stayed there until we left the region. We asked our neighbours about our ghost but none of them had ever heard of her’.

The area occupied by the operational troops and their officers was called The Lines that consisted of lines of containers used as accommodation modules and for other uses. One them served as a church and I was able to attend Sunday mass there. The chaplain was a Derek Nimmo type character and was a transparently spiritual man. There was one ceremony that stood out and this was the reception into the Catholic Church of a soldier. It was important enough to warrant the appearance of the Chief Chaplain of the British Forces, a bishop, who conducted the ceremony. God works in mysterious ways even in the midst of war.

Finally, there was a small hospital under canvas that I had to attend when my hand swelled to double its normal size after a bite from a desert sandfly. Injured soldiers were treated here and those who warranted it were transported to a military hospital by air.

A troop casualty being transported to hospital. Note the two Nimrod aircraft to middle right of photo.

In no time I was transferred over to The Lines no doubt because of my snoring prowess. The Lines consisted of a row of large corrugated arches, positioned so that every alternate one was some metres higher than the ones adjacent to it. Under the arches were of rows of container-like huts that housed two residents each and each Line had a military name. Toilet and showering facilities were housed in containers in the middle of the complex. Again visits to the toilet were uncomfortable forays during the cold night with a heightened awareness that one could be in some insurgent’s rifle sights. We were used to isolated mortars coming in but thankfully they caused no damage in my time there.

My ‘container’ quarters in the Lines.

Next to The Lines were rows of tents for the soldiers. Interspersed between the tents were large rubber water containers about 20 feet x 20 feet x 3 feet. The rubber was treated to self seal in the event of being punctured by a bullet.

The Lines canteen was near the gate to the compound and a number of Iraqi anti-aircraft guns and howitzers graced the space in front of it. Just at the gate were large insignia of some Irish regiments who passed through Basra.

Finally, I was promoted out of The Lines and given a place in the mercenarys’ compound. This was sheer luxury compared to my former abode. I had a two-room chalet with separate bathroom to myself. The place was well-sandbagged and was occupied by the mercenaries as well as a few rooms allocated to USAID people. It had an excellent dining room and bar where the ‘two drinks’ rule was largely ignored. The mercenaries were by and large foul-mouthed, swaggering louts and to my dismay I noticed a few Irish accents in the group. I passed them as I went to my office each morning as they cleaned and oiled their rifles and machineguns at the doors of their quarters while waiting for their armoured transport to arrive.

My office was only 100 metres from the mercenarys’ compound so I went out the back gate and saluted the Gurkha sentries who were delighted to pose for me. The office was of similar construction to my quarters and was furnished by IKEA units from Kuwait. Our Iraqi employees were Christians from Basra and were mild, inoffensive people who I feared for when the coalition armies would pull out of Iraq. One day one of them made me a present of a red and white keffiyeh with its agal. The agal is the black cord holding the keffiyeh in place that evolved from the rope that the Arabs used to fetter their camels. I must have a very big head because the agal was much too small to hold anything in place as was the one I got in Jordan. The Iraqi workers were bussed into the base every morning and were searched at the entrance gate before they were allowed entry. The same procedure was followed when they left in the afternoon. As part of our security briefing we were instructed to shred all personal documents. This stemmed from the British Army experience with the IRA in Northern Ireland where the cleaners in their bases there scavenged through the rubbish bins and acquired knowledge of individual troops that they used to deadly affect. Most of those who served there acknowledged that the Iraqi insurgents were then much inferior to the IRA.

Before I was allowed out of the base I had to undergo a course on IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices). There was a display of IEDs and road mines in the base and we learned the modus operandi of each type. I was assured that the troops were trained to protect my life if necessary at the cost of their own and had to practise what was to be my knee-jerk reaction in the event of an ambush. I was taught to roll out of the vehicle and to crouch behind a wheel or play possum in the roadside gutter while my escort attended to business. This advice was hard bought but very wise. In fact it saved Edward White, my father-in-law’s life. He was acting as an outer cordon scout protecting Flying Column of the famous Third West Cork Brigade of the IRA on 19th March 1921. The entire armed Brigade (limited by the arms in their possession to 100 men) was in position at Crossbarry, County Cork and was being encircled by 1,300 soldiers of the British Army, led in part by Percival of Singapore. Edward was crossing a road and was captured by the British troops at 4 o’clock in the morning. They used him as a hostage and tied him to the protective wire netting (used to protect the occupants from IRA grenades) on their Crossley Tender truck so that he was in full view of anyone on the road. He would be shot by the troops in the event of their being attacked by his comrades. Soon the truck drove into the ambush site and was immediately overturned by a mine. Edward rolled clear and into a roadside culvert where he remained until the battle that raged over his head was over. When he emerged he carried a Lewis Machine Gun and eight pans of ammunition he had salvaged from the dead soldiers in the truck to a grateful IRA quartermaster.

At the time the Iraqi insurgents would detonate their IEDs with their mobile phones as the troops passed over the IED but the time the detonator took to explode meant the troops had passed and escaped. The insurgents then operated the detonator at a fixed distance before the IED position so that the IED would explode as the troops passed over. The military believed that this refinement as well as many others was as a result of the insurgent’s collaboration and training with Iranian Military.

Each day the security people would sound the security alarm and the fire alarm to familiarize the troops with the sound of each. In my time there the real security alarm sounded a number of times when the dog sniffers at the main gate would detect the odour of explosives. After a number of minutes the ‘all clear’ would sound and normal activities would resume.

The area of the base was huge and as I am an early riser I used to go for a long walk each morning before breakfast. The dawn desert air was quite cold and pure and in this bracing atmosphere, I could well empathise with those Europeans who fell in love with the desert and its feeling of solitariness. British (NAAFI) and American (PX) shops kept the base well-served with all the goodies young people would need. The American one would never give coins as change but tin tokens in lieu of the different coins. The base was equipped with its own ‘Hill’ (a sand coating and protection for the base water tanks) and it was used for health and possibly punishment. The ones I suspect were on punishment runs usually carried huge loaded rucksacks or berms and the sight usually put me in mind of the Sean Connery film The Hill. In fact, I saw many soldiers carrying out their normal duties around the base carrying those loaded rucksacks.