Chapter Forty

Road and River Patrols from Basra

Eventually the day came when I was able to leave the base. I got into a snatch wagon and sailed out with my protection squad of two truckloads of soldiers in front of me and two behind together with a sort of rapid response snatch wagon. As I was in the middle of the convoy I felt that I would be regarded as a prestigious target for any ambitious insurgent seeking promotion. I was conscious that there was only the canvas cover of the snatch wagon, to protect me from any spray of bullets from his weapon. When we eased out of the main gate of the base we were in hostile territory. We passed many checkpoints with long queues of cars tailing away from them and an helicopter gunship circling overhead. When we slowed down I could feel waves of simmering hate emanating from bystanders on the footpath. They were not enamoured of their ‘liberators’ but then the Allied armies left them at the mercy of Saddam after the First Gulf War and then imposed crippling sanctions on them for years afterwards.

We usually kept to side roads until we were well clear of Basra City. This detour frequently took us through the city garbage dump. As we drove through the stench of the dump I noticed scores of Iraqis trawling through the rubbish of a starving city. Some soldiers pointed out a line of warehouses to their comrades and explained that some British soldiers were charged with torturing Iraqi prisoners there. From the reaction and comments of my protectors I felt that such behaviour was repugnant to them.

On other occasions we would travel on a runway of one of Saddam’s airbases if we were going to a power station or the Shatt al Arab. Looking back I feel that we were naïve as it was just after the war and the insurgency was in its infancy. On many occasions we had to wait outside power stations while calls went out to the Iraqi engineers, who for some reason had disappeared before our meeting appointment, to come and meet us. They were very dilatory in turning up and I often felt that they were warned off by insurgents who could be preparing to ambush us.

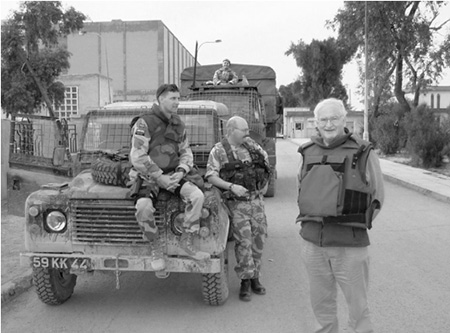

Waiting for our Iraqi engineers. We were very exposed to potential ambushers here. My counterpart, Major Larsen of the Norwegian Army is sitting on the bonnet of my snatch wagon and a British Territorial Army major is between us.

The senior Iraqi engineers were Sunni Moslems to a man but the security guards at the power station gatehouse had the walls covered with images and sermons of the Ayatollahs and Shia clerics. The Sunni managers told me that Shia clergy (they called them ‘the men in turbans from Iran’) had met with the power station workers and instructed them to replace their Sunni managers with ‘elected’ Shia ones. This process was being implemented at the time. My road journeys took me all over the oilfields of the south where I visited power stations and traversed across the desert inspecting transmission lines. These power stations and transmission lines were of global strategic value as their main function was to keep the southern Iraqi oilfields feeding the world economy. Any major failure would have worldwide consequences.

Progress along the highways was stressful. On our almost daily patrols the convoy would speed along the highway and the soldier manning the gun in the lead vehicle would order all traffic ahead of us to pull into the side to give us free passage roaring through his bull horn “Pull in or I will shoot.” This behaviour annoyed my regular driver, a sergeant in the Royal Marines, who told me that the Iraqis would report arrogant behavior to the insurgents who would attack the man’s unit within days, which they did. “He is behaving like the Yanks and will have us all killed,” he muttered to me. Then he contacted the man’s NCO and shouted into his radio: “He will single out his regiment for an insurgent attack.” I became quite friendly with this sergeant and we often discussed his time in Northern Ireland where he developed a healthy respect for the abilities of the IRA, who he judged as being vastly more deadly than the Iraqi insurgents.

It was particularly tense at intersections when our rapid response snatch wagon would race ahead to the crossing, the soldiers inside would jump out and control all roads leading into the roundabout or crossroads while the man manning the cab roof machinegun in their vehicle would provide back-up. All traffic would be stopped except on the road we were to use and we sped through. I felt vulnerable as I was flagged as an important target in my armoured car and would be the first to be acquainted with an IED (Improvised Explosive Device) if the insurgents decided to attack my convoy.

When I had to pull in off the road and cross the desert on foot the soldiers would dismount from their vehicles and form a cordon around me and would go to ground when I stopped. The countryside was quite monotonous as it consisted of scrub and irrigation canals of the former country of the Marsh Arabs. There was some activity, however, as local farmers harvested salt from the coast in their age old way. This was of interest to me as the high incidence of salt caused havoc to the high voltage lines serving the oilfield installations.

Stopping near Rumalia. On this occasion I was given an armoured plated saloon while my protectors travelled in vulnerable snatch wagons. One of the soldiers can be seen gone to ground behind the rear snatch wagon.

Most of the roads to the south skirted the Shatt al Arab and it was common to see the superstructure of a ship moving sedately and towering over the bushes about 200 metres to the side of the road.

I had to attend meetings at the office of Mr Abbas, a Sunni, the local Electricity Company CEO. The ante office was usually full of local sheiks, clad in up-market thobe, keffiyeh and agal, as they waited for an audience. These were the local tribal leaders who were trying to obtain work for their respective tribes. One source of paid work was to ‘guard’ the damaged power lines from further damage. When the Coalition ‘Bremer’ Administration heard that this was going on they ordered the military to put a stop to it. This was done and the following morning all the towers the tribes had been guarding were knocked over. At a meeting I attended to discuss the development I was aghast to hear an American Colonel advise: “Shoot them.” The tribes themselves were warlike and many British Officers in outlying barracks told me that they could not sleep at night from the sound of gunfire as rival tribes settled their differences.

On a number of occasions I was taken to a site where tests were ongoing on researching methods of erecting electricity towers in the desert. They were to be assembled in a steelyard near a city, then transported by helicopter to their site in the desert and bolted to steel stubs protruding from the tower’s concrete foundations. On the test site a tower was lying on its side fully assembled and right next to its four foundations (one for each leg of the tower) with a steel stub protruding from each foundation. A Chinook helicopter was landed nearby and its pilot, in this case a young blonde lady, was discussing the lift with the Iraqi engineers. Then she lifted the helicopter with the completed tower slung underneath and approached the stubs where men were waiting to bolt a tower leg to each stub. The tower swayed alarmingly like a huge pendulum and no matter how often the nerveless pilot approached the stubs the ground crew were unable to steady the heavy tower long enough to secure it to the foundations.

The lady pilot attempting to set the tower on the foundation stubs.

This technique is used in the US and Canada for building transmission lines in remote areas. There, they assemble the towers in about four pieces at their HQ and find the smaller pieces much easier to transport, manipulate and attach to the foundations. They then build the tower, one assembled piece on top of the other. As can be imagined it is very difficult to map and record the position of each tower in the vast featureless desert. This problem was solved by using a helicopter to patrol the line and record the helicopters GPS (Global Positioning System) position at each tower.

I will never forget an incident that occurred as I walked across the sand over the southern oilfields at al-Fao near Basra. I had to drive off the highway and onto the desert so my minders did likewise and drove after me. My upbringing was Republican and when I looked back at my guardians it dawned on me that these soldiers who were no more than silhouettes in their trucks were prepared to sacrifice their lives to protect me. My core prejudices took a sudden reappraisal I assure you. I had been reared on the stories of my uncle, a commandant of the 2nd Cork Brigade of the IRA, or my father’s cousin killed at the Kilmichael ambush and later of my father-in-law at the battles of Crossbarry and Upton, all from the 3rd West Cork Brigade Flying Column. Now I was to experience being at the receiving end myself.

When I reached my objective the soldiers dismounted and surrounded me. I moved across the desert and they moved with me keeping me in the centre of their circle. When I stopped my escort stopped and went to ground. It reminded me of my days in the 48th Battalion of the FCA (Irish Territorial Army) when we wandered across country during our military exercises. Then it was great sport and many flippant jokes went the rounds as we trudged through furze bushes or landed in cow pats when ordered to take cover. This time it was deadly serious and the Tommies were silent as they moved.

Suddenly we were approached by a small Arab boy running across the sand. Twenty rifles pointed at him and their owners meant business. The most effective suicide bombers come in very innocent guises. I was ordered to go to ground as the soldiers scrutinized him. Eventually they were satisfied that he was what he appeared to be. The poor little chap was begging for water. He was joined by his father who ran up in great agitation to defend his son. When the situation clarified eventually, he too began to look for water. I thought how obscene it was to witness this little cameo. Here he was, in his native land, standing over a lake of Iraqi oil and when he should have immense wealth did not have clean water to drink. The Tommies who were charged with the unenviable task of maintaining this status quo and with defending my life with their own, put security to one side and gave them their bottles of water. The young boy was a plucky little chap and insisted I take his photo with his dad.

The young boy who looked for water at al Fao with his dad.

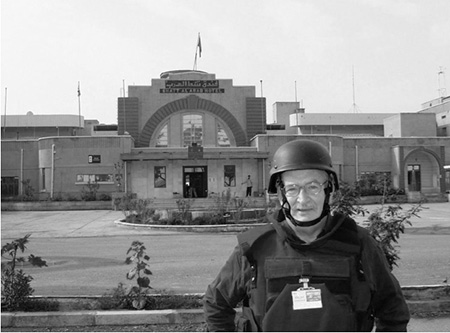

Many of my meetings took place in Saddam’s palace on the Shatt al Arab and I used to look forward to them. The palace was then a British Battalion HQ housing 700 soldiers. The route there took me along the airstrip ‘road’ to the Shatt al Arab Hotel (This was also a British Army Battalion HQ housing 600 soldiers until it was handed over to the Iraqi Army in 2007) on the riverfront that is now derelict. We embarked on a high speed commando boat at the pier attached to the Hotel. As we sped along the Shatt we passed many war wrecks scattered at random along the waterway.

The author at the Shatt al Arab Hotel on the Shatt al Arab at Basra.

We finally reached the palace, a very imposing building on the riverbank that jutting out arrogantly and commanded magnificent views of the Shatt in all directions. We moored at the exclusive quay of the palace where a number of snatch wagons met us and conveyed us to our respective meetings in various guest houses scattered around the huge palace complex. What stood out was the greenery of the place in contrast to its arid surroundings. There was a labyrinth of roads crossing and re-crossing the bridges over the canals that eventually led to the various palace buildings. I felt that this place was symbolic as a base of an occupying army but was very vulnerable to attack as it was difficult for a relieving force to reach easily and was surrounded by marsh and scrubland on the landward site. When there was talk of my staying in Basra the package included undergoing an anti-interrogation course given by the SAS in Kuwait and a relocation to Basra Palace. I was glad when I did not consider the option as the palace that had a garrison of 700 soldiers was attacked by the Madhi Militia with rockets and mortars in 2007 and it had to be abandoned.

When the meetings concluded we returned to the palace boat dock. We were informed that the boat that had brought us to the palace had mechanical problems so we had to return to the Shatt al Arab Hotel on two Rigid Raiders. These were high speed assault boats used by British Commandos and SAS. They were literally like floating plates with very, very low gunwales. One had to sit on the floor and hold on to rope loops on the gunwale. The boats took off at 30 knots per hour and the fun began as it took off over the water in a series of bone-jarring hops. The hull of the boat lifted out of the water with the speed and it crashed down to the surface again with a thud when it hit any turbulence. Turbulence there was aplenty from the wake of the raider in front. The hull was solid and each time it hit the water the impact on ones bottom and spine was severe indeed. I had a feeling of great vulnerability and wondered how I would cope in the event of a capsize in the filthy water as I considered the Shatt to be the excretory organ of Iraq.

Just a short distance from the palace the marine steersman made a sudden turn to the left making the boat stand almost perpendicular in the water and headed straight to a small mashoof (a boat common to the Marsh Arabs near Basra). There were two fishermen in it and the steersman ordered them to leave the area and stay away. If they returned he told them they would be shot. I was told later that they were part of the insurgents’ intelligence network as they noted all the movements within the palace the information to be used in the sure event of an insurgent attack. When I returned to my quarters, my behind, thighs and legs were black and blue and I had difficulty in sitting for some days afterwards.