Chapter Four

Journey to Work in Baghdad

The bedside phone shrilled at half six; it was the hotel reception to tell me that my driver was waiting for me. During a sleepy exchange I was told of the hour time differential between Amman and Baghdad, so my journey of the previous day across the desert had crossed a time zone. I instructed the driver to return in an hour and rolled out of bed. Then I went out to the balcony to see Baghdad in daylight and shivered in the invigorating pristine cold air. The sense of well-being was as pure as the May days I remembered as a child. The sky was cloudless as I looked around from my 12th storey eyrie.

I took the lift to the foyer where I saluted the Mukhabarat (Saddam’s secret police) man, whose job was to monitor all who entered and exited the hotel lifts. Like all his colleagues in the Hotel Babylon he was well-dressed and very courteous, though distant. He had none of the brooding menace of his equivalents (ex-KGB) in Kiev. While we were there, an informer in an Artioma Street apartment building we were visiting, contacted the immigration police and reported that foreigners were seen entering and leaving an apartment in the building. In Soviet times each apartment block had its own commissar whose duty it was to report suspicious or anti-state behaviour. So the former commissar in this apartment block was loath to give up his position of power and persisted in carrying out his policing duties right into the post Soviet era. In Artioma Street many of the apartment buildings had their doors in the back and had to be approached from a rear courtyard, via an arched carriage opening off the street. All house doors opening on to the courtyard were permanently open and the snow would form drifts in the hall in the night temperature of -20oC.

The street, courtyard and the hall were in pitch darkness and we had to pick our way through the snowdrifts with torches that were mandatory. Avoiding the snow-covered and foul-smelling Ladas and scattered motorbikes, laid up for the winter, we entered our friends’ house one night and noticed two men on the stairs above us furtively examining the numbers on all the apartment doors. Shortly after we had entered our friends’ apartment, via its inner and outer steel security doors, the bell rang, there was loud banging and someone was yelling in Ukrainian. As there were four of us in the room we were confident that we were able to look after ourselves so we opened the doors to be confronted by the two men we had seen on the stairs. One was dressed in a leather hat and long leather greatcoat and the other was armed and wore a helmet, leather jacket and long leather boots. They were immigration police and when we could not produce our registration documents were clapped in handcuffs.

At the time the USSR had just disintegrated and I reckoned that the old Soviet prisons had not caught up with the new political realities of the Russian Federation. I pictured myself being shipped off to a gulag in a cattle wagon. However a quick-witted member of our group, Michael Crowley of Mallow Co Cork, saved the day by phoning Uri, our liaison contact, behind the policemen’s backs. Uri, who had previously worked in the Immigration Department, contacted the relevant government official who ordered our captors to free us. This they did after a long one-way interrogation when they insisted on asking the same aggressive question again and again despite all our answers: “Where are your registration papers?”

We were euphoric when we were let off the hook as the photo demonstrates.

A very relieved pair, Louis Healy left and the author right show off after being informed by Kiev Immigration Police that we were no longer under suspicion.

Back to the Hotel Babylon in Baghdad, I was quickly located by my driver who introduced himself as Ayad H Humayde. The UN has a custom of recruiting local people with university degrees relevant to the work of whatever UN agency that employs them. In the Electricity sector, therefore, this meant that most of my Iraqi staff were engineers or had technical degrees. Hence Dr Ayad, who had been an electronics lecturer in the University of Baghdad, became one of my drivers. I felt like the proverbial ‘Pukka Sahib’ as I seated myself in the white air-conditioned Toyota Land Cruiser waiting for me in the car park, with the letters UN emblazoned on its side. We eased out past the security guard hut at the hotel gate. On a plinth near the gate was a large black basalt sculpture of a lion kneeling on the body of a man, crushing him. This was the symbol of the ancient city of Babylon, south of present day Baghdad. Outside the gate the road widened to form a square. It was named Ba’ath Square (after Saddam’s Ba’ath Party, Ba’ath means resurrection) as if to proclaim the loyalty of the place to Saddam and his courtiers and the knowledge of the name definitely did not lift my mood.

The Lion of Babylon is now an accepted symbol of Iraq and Saddam was one not to miss a promotional opportunity. He empathised with Nebuchadnezzar II the builder of Babylon. He reasoned that this would appeal to the Iraqis as Nebuchadnezzar, who is mentioned many times in The Bible’s book of Jeremiah, vanquished the Jews and destroyed Jerusalem. Saddam decided that he was just the man to emulate him. In The Bible, Nebuchadnezzar is quoted by Daniel (4:30) as saying: “Is not this the great Babylon, which I have built to be the seat of the kingdom, by the strength of my power, and in the glory of my excellence?” To the disgust of the world’s archeologists Saddam proceeded to rebuild Babylon. He spent over $500 million in the process. He brashly copied Nebuchadnezzar by having his name and praises incised on the new bricks. Some read ‘To King Nebuchadnezzar in the reign of Saddam Hussein’. Others read ‘This was built by Saddam Hussein, son of Nebuchadnezzar to glorify Iraq’ More again read ‘In the era of Saddam Hussein, protector of Iraq, who rebuilt civilization and rebuilt Babylon’.

Saddam Hussein’s workers laid more than 60 million sand-colored bricks but unlike their predecessors, the new bricks began to crack after only 10 years. Saddam also built a magnificent 600 room palace for himself looking out over Babylon and the Lion of Babylon.

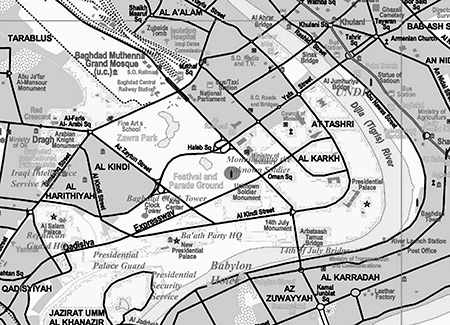

Babylon Hotel neighbourhood. (The map is from the 2003 Special Reference Graphic Map of Baghdad by NIMA.)

Ayad eased his way into the heavy morning traffic and then steered for the road running along the river bank towards Abu Nuwas Street. We sped under the Arbataash Tamuz Bridge (also called The 14th of July Bridge) and could see, through the shrubs to the far bank, the living quarters of some of the elite, including what I was told were the deserted homes of General Husayn Kamil and his brother Saddam.

These were the ill-fated sons-in-law of Saddam Hussein who fearing the increasingly erratic and violent behaviour of Saddam’s eldest son, Uday, and his militia of young thugs, called Fedayeen Saddam (‘Saddam’s Men of Sacrifice’) escaped out of Iraq on 8th August 1995. They were enticed back by Saddam who guaranteed them safe passage on 23rd February 1996. On their return they were immediately divorced and quickly killed by their own tribe at the instigation of Uday. While there was great sympathy for the brothers in the West I include an image of an officer purported to be Husayn personally executing a man bound to a stake by shooting him from behind.

As we drove along beside the river, the Mujamma’ Dijla (‘Tigris Compound’), housing the Revolutionary Command Council, Regional (Iraqi) Leadership, a huge truncated pyramid of a building, was just across the river on our left. The Revolutionary Command Council was the theoretical government of Iraq. No one would believe that the craven, cowering, uniformed bunch that appeared frequently with Saddam on world TV screens could make a decision on their own. They literally looked in fear of their lives, with some justification. Its official name is the Zaqqura Palace; the name Zaqqura comes from a step pyramidal temple near Ur where the ancient peoples of Babylon and Ur offered gifts to their gods in celebration of spring. Most of the gods had altars on the pyramid but nearly all the gifts were offered to Marduk, the city god of Babylon. It seems a perversion that a name associated with joy and happiness was hijacked by Saddam to denote a building where murder, cruelty and mayhem on a demonic scale was planned and directed. The RCC Building was severely bombed in 2003 and is now useless.

The badly damaged Revolutionary Command Council Building post “Shock and Awe” Bombing. The large building to the extreme right across the Tigris is the Sheraton Hotel and the tall building to its left is the Palestine Hotel.

Photo source: SSgt Cherie A. Thurlby, USAF.

Further on, we passed two large hotels, the Palestine Hotel formerly the Meridien Hotel and the Hotel Ishtar, formerly the Sheraton Hotel. They looked rundown and forlorn with many of the windows broken or boarded up. They were facing out over the Firdos (from Fardus meaning Paradise) Square with its famous statue of Saddam sited on its eastern side. This was the statue that got worldwide exposure as it was pulled down by US soldiers on 9th April 2003.

I noticed many old orange and white VW Passats. Thousands of them were imported into Iraq from Brazil in the 80s by the Iraqi State Company for Cars and the rumour was that they were part payment in an arms deal. They were unpopular as their air conditioners were unable to cope with the high temperatures of Iraq but thousands of them still survive. It was said that Saddam had given them to his demobbed soldiers for a few dollars each. This was at a time when one Iraqi dinar was worth three dollars. During my sojourn the exchange rate was 1,860 dinars to the dollar.

Most of the larger buildings we passed merited military guards. The guards, mostly conscripts, were casual and wore their berets like chefs’ hats instead of the smart flattened style affected by the Western armies. It reminded me of our FCA (Irish Territorial Army) at home during an ambush exercise. I was in a platoon advancing along a road sans helmets and we were to be ambushed by a rural platoon who wore their berets in the Iraqi style. As we advanced we were confronted by a row of beret tops sticking up over a ditch, worn by our would-be ambushers. We pretended not to notice as we waited for the fusillade of gunfire (blanks). The Iraqi officers though, were much higher in the sartorial league, being well togged out in super-fines (uniforms of officer-grade material as distinct from the inferior material of the uniforms of the other ranks) and with a distinct military bearing.

Pockets of buildings had sustained bomb damage, many of them small rundown hovels in dismal poverty-stricken laneways off the river. I wondered how many innocents had died there after a lifetime of miserable existence under a dictator, to be savagely and painfully killed. Many must also have lost their livelihood and watched their wives and children slowly waste in this desolate city, the city that was once the jewel of learning and civilisation. It was a panorama of ruins where most of the larger public buildings were just hollow, blackened, windowless hulks.

Ayad indicated the many fine bridges crossing the Tigris and proudly pointed out that most of them had been destroyed by Allied bombing in 1991. However, they had become operational again within a short time, thanks to the skill, drive and ingenuity of the Iraqi engineers, who repaired them with whatever materials they could lay their hands on. He recounted the story of the American pilot who began his bombing run on one bridge but before he released his deadly cargo saw a number of cars on it. He aborted his attack and circled back for a second run to destroy the bridge when it was clear of civilians. Later I heard of this incident many times by other Iraqis who praised the humanity of the pilot who refrained from pressing the button of death in his safe and practically invulnerable cockpit.

My road to work. The tree lined Abu Nuwas Street with the Ishtar Sheraton Hotel in the foreground and the Palestine Hotel behind. This area is now the Red Zone with the Green Zone directly across the river.

Photo: Courtesy of Robert Smith.

Abu Nuwas Street is named after the eighth century Arab poet who was a libertine and an icon of the gay community, most of whose poetry was devoted to homosexual love. He could best be described as a gay Omar Khayyam. This was quite acceptable in Islamic medieval times but the attitude to homosexuality is now more ambivalent in Iraq. Abu Nuwas’s bronze statue weighing in at 2.5 tons is situated in the street named for him. It was created in 1972 by the Iraqi artist Abdul Fattah Al Turk, who also designed the turquoise blue split dome of the Al-Shaheed Monument (Martyrs’ Monument) in 1983. After the invasion an Iraqi entrepreneur acquired the bronze goblet that Abu Nuwas held for its bronze content. It has since been replaced.

Statue of Abu Nuwas.

Photo: By kind permission of Bassam Haddad, Assistant Professor, Department of Public and International Affairs, George Mason University Fairfax USA, from the film ‘About Baghdad’ by Incounter Productions.

Then, on our left, at the water’s edge we passed the children’s playground with the massive statues by sculptor Mohamed Ghani Hikmat of King Shahryār and Scheherazade as she weaved her tales for 1,001 nights, a reminder of the city’s past history and heritage. King Shahryār had married a beautiful lady but she was unfaithful. When the King was told he had his wife executed. Thereafter he grew dis-enchanted of the fair sex. He took a beautiful girl into his bed each night and to avoid being cuckolded had her executed the following morning. At last it was Scheherazade‘s turn so she narrated such a wonderful story that when morning came the King postponed her execution for a day. He wanted to hear another story. Each day thereafter Scheherazade recounted story after story and stayed alive for 1,001 nights until the King cured by her therapy married her and they all lived happily ever after.

At last we turned right, up a miserable laneway and stopped before our destination, the Sadoun Building.

Scheherazade Narrator of the Arabian Nights.

Photo: By kind permission of Bassam Haddad, Assistant Professor, Department of Public and International Affairs, George Mason University Fairfax USA, from the film ‘About Baghdad’ by Incounter Productions.