Chapter Five

Journey from Work in Baghdad

The Sadoun Building was occupied by a number of UN Agencies and was my work base when I was in Baghdad for the following few years. We climbed the entrance steps and passed the customary Iraqi military guard. In time I became quite friendly with these very shy and courteous conscript guards and I always stopped to discuss the merits of their weaponry, which they proudly showed me. We also had some joke to exchange as it was not customary to discuss the weather in this city of perpetual sun and blue skies. Coming from Ireland where the weather is fickle and provides ample opportunities for comment and speculation, a guaranteed opener for social conversation, I was surprised when people looked at me as if I was mentally challenged, when I would first open a conversation with: “Isn’t it a grand day today.”

The Building was once a maternity hospital and was little altered from its former use. The UN security people now occupied the main hospital reception area and I was steered through their procedures by Ayad. My agency, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) was on the fourth floor. The UN observers also used the building and on most mornings they assembled in the tiny foyer and over-spilled down the steps outside as they were briefed for the day. These briefings were initially carried out by Ms Khan, a sister of the Pakistani politician and cricketer Imran Khan, but were later taken by Noel O’Regan, a fellow Irishman, and a native of Croom, County Limerick. These observers tracked and verified every aspect of the material movement of the Oil for Food Programme, as it applied to Saddam-controlled Iraq, from the entry of an item into the country to its final installation in the designated location. The Sadoun lifts were huge, designed to accommodate patients on trolleys with their attendants. We had the choice of three and they did not always work. Many were the mornings when all three had refused to operate and we had to trudge up the four flights of stairs to our office, hearts pounding from the strain, the heat and the effects of the Hotel Babylon’s strong Turkish coffee.

My UNDP/UNDESA Energy Sector international staff, spent a considerable amount of their time dealing with enquiries for clarification from the UN Sanctions Committee (the Sanctions Committee’s task was to rigidly apply sanctions guidelines and avoid approving items that could have a dual i.e. military use.) in New York, was waiting to inspect me when I entered. They also prepared material for the UN 90-day report which reflected the programme progress to New York and for the 180-day report to the Security Council that chronicled the progress of each phase of the programme that was renewed every six months or 180 days. All other work stopped during the compilation of the reports as draft after draft was changed to portray a good positive image for the programme. The pecking order in the UN was enhanced by a person’s perceived skill in report writing. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn maintained in his novel A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich that it did not matter what work was done; what mattered was what appeared in the Gulag work report. Skill in work reporting meant that you ate well; this lesson was well-applied in Baghdad.

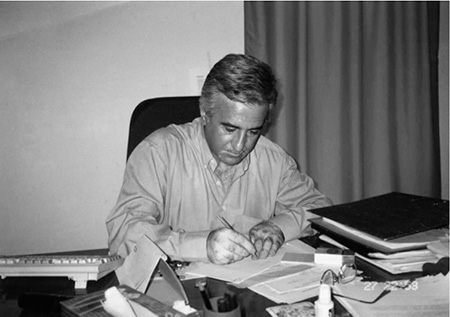

Abdalla Odeh, the UN Residential Representative (Ambassador), my boss in Baghdad, came to appraise me later in the morning. He had an autocratic management style and was feared by all. His days out of Baghdad were termed Odeh-free days by the staff, in a noticeably relaxed atmosphere. His wife and family lived in Amman and he told me that when he would be particularly stroppy he would find a basket of dates on his desk in the morning. As the Arabs regard dates to have aphrodisiac properties he would take the hint and make for Amman. He was almost bald, lithe, slim and a bit saturnine with refined Semitic features.

The following day, Sunday, I met the nationals. Imad Subhi Hanuddi, was the corner stone of the sector in Baghdad. We shared an office and struck up a friendly personal relationship. I visited his house in the up market Harthiya District a number of times and got to know of the tensions the normal Iraqis were labouring under. He told me of the bombing raids and the effect it had on his young daughters. When there was a possibility of renewed bombing at the end of 1998 he said the girls were hysterical at the prospect of enduring the fear and terror again. They remembered the horror and turmoil they endured on June 27th 1993 when US President Bill Clinton ordered the bombing of Baghdad, ostensibly in retaliation at the attempted Iraqi assassination of ex-President Bush Senior, as he visited Kuwait in April 1993 to celebrate the victory over Iraq in the 1991 war. The real reason, it was suspected, was to divert attention from the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

On June 26th 1993, on the Red Sea, the destroyer USS Petersen fired 14 Tomahawk Missiles with the Directorate 14 of the Iraqi Intelligence Headquarters in Baghdad as their target. This Iraqi Intelligence Directorate was fingered as being responsible for the attempt on President Bush Senior’s life. Simultaneously out on the Persian Gulf the cruiser USS Chancellorsville fired nine Tomahawk Missiles at the same target. The missiles, which each cost an estimated $1.1 million, and were capable of carrying up to 1,000 pounds of conventional explosives sped to Baghdad on their two-hour journey. They struck their target between 1.00am and 2.00am local time on June 27th 1993. One can see the closeness of the Iraqi Intelligence Headquarters and the Harthiya District by referring to the map at the beginning of this chapter. Three of the missiles went astray; one of them with a payload of 450kg of high explosives struck the Harthiya District less than 100 metres from the Intelligence Building. It hit the house of the beautiful Layla Attar, the most prominent lady artist in Iraq and Director of the Saddam Hussein Centre of Arts. Layla who was internationally known and respected had just retired for the night and she was killed instantly together with her husband and maid. Her son and daughter were also in the house when the missile struck. Both were severely injured, her daughter unfortunately lost her eyesight. The missile destroyed three houses in the vicinity and shook Imad’s; in total eight civilians were killed. USS Petersen earned a battle efficiency award for the exploit. The story made a strong impression on me as I thought of the threadbare Iraqi conscripts who would have to face such daunting odds. Kris Kristofferson composed and dedicated a song to Layla and the Argentinian Disappeared (Los Olvidados) called The Circle in 2003.

Imad appeared to be well-to-do although a Christian. He came from the same village as another Christian, Tariq Azziz the very able spokesman for Saddam Hussein in his frequent conflicts with the UN and the USA.

On my visits to Imad’s house I saw a large steel lattice communication tower in the trees nearby. I was told that this tower was the missiles’ target. In my naivety at the time I supposed that one of the missiles went unimpeded through the lattice and wrought the civilian damage. Imad made no mention of the Intelligence facility. I feel now that most Iraqis were in a state of denial because of the terror they endured. Imad’s house was large with polished wood floors festooned with Persian carpets while Persian rugs lined the walls and framed an impressive grand piano in the lounge. My impression of Iraqis before I arrived was of wild warriors on camels like those who fought with Lawrence of Arabia. After my visit to Imad’s house I became aware of the sophisticated culture of the educated élite.

Result of Missile attack.

Phto: Source image 36 US National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 88.

Imad Hannudi.

He was a true friend when I first arrived in Baghdad and helped me in every way he could. For example, when I got married I thought it was very effeminate for the groom to wear a ring and decided I wouldn’t wear one. I was reminded of this many times during my married life and eventually put on a ring that belonged to a grand aunt of my mother’s. She had lived through the Irish Famine of 1846 and remembered the bodies found in the fields with their mouths stained green from eating grass. I was proud of this ring but its history made no impact on my wife who wanted me to wear a ring solely for her. As absence makes the heart grow fonder I made up my mind one day and Imad took me down the Karrada to a jeweller friend of his and the deed was done. I purchased the ring and one more casus belli was removed from the domestic hearth. It is a constant reminder to me of a very good and true Iraqi friend. Shatha Kamel Chakmakchi (Al-Yaseen) was our accounts lady. Her young son had died in her arms after the 1991 bombings from a routine childhood illness, measles. He developed complications and died from want of common drugs. “Mr Dan” she said to me “our riches are our greatest curse.”

Finally, I met Amer, the office boy whose job was to circulate the post and to provide the office workers with liquid refreshments from the ‘canteen’ on the landing outside. This usually consisted of Turkish coffee and after one or two sips, unless you were a corpse, you were in top gear. The top half of the glass contained the liquid coffee while the sediment and dregs filled the bottom half so a glass of water was mandatory to wash out the bitter, invading grains. Tea laced with 50% of sugar, served in the small bulbous glass, or as some Irish pint glasses are termed, pregnant glasses was also available as were various fruit juices. With such an emphasis on sugar it is no wonder that diabetes is rife in the Middle East.

Amer was our liaison man with the moneychangers who changed dollars into local Iraqi dinars. On average he would change about $200 each time. It is worthy of note that although he performed this service every day and it was no secret, he was never robbed. There seems to be a lesson here, when the governing regime is autocratic with draconian penalties the local yobs seem to disappear only to come out of the woodwork with democracy.

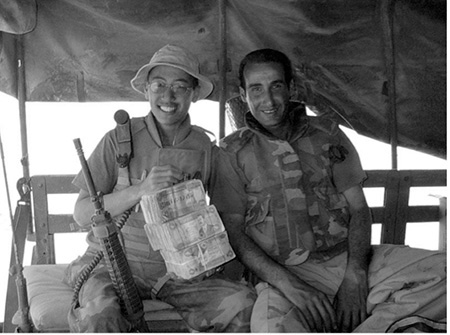

Ray Cheung of the US army poses with $100 dollars worth of Iraqi Dinar. Imagine the size of Amer’s bundle when he would change $200.

Photo: R.K.Cheung, US Army.

When I got to know Amer better he included me in his office shopping list for lunch and would return from the nearby shawarma stands with deliciously hot shawarma (Arabic for doner kebab) sandwiches or guss as they are called in Iraq. These are usually sandwiches of slivers of either chicken or lamb which are shaved from a vertical rotating spit that slowly roasts the meat for at least a day. The meat is then heated on a hot plate with tomatoes and garnishes and finally stuffed in pitta bread; delicious!

In the office I was allocated a table used by my predecessor, without a phone or desk-top computer in a corner of the office I was to share with Imad Hannudi. I had to share Imad’s phone and internet access when he was out of the office. I thought this dearth of the basic tools of management odd in the extreme and flagged the local UN lack of understanding of the immensity of the project. Here was I, appointed to be the International Co-ordinator of the Electricity Sector, the largest sector in the biggest UN Aid Package in history without an office phone or personal access to the internet. At that time the existing sector budget was $420 million. Significantly, I later met with our former Irish President Mary Robinson when she was UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in the New York UN Building and it transpired she suffered the same type of bureaucratic restrictions.

When I became aware that the Mukhabarat had hacked into the UN communication networks I frequently sent my messages to Liam Tobin of ESBI in Dublin in Gaelic and no doubt gave many a headache to my monitors of whatever persuasion.

Due to its corner position my work station provided some shelter from the freezing draught as the Shamal roared through the ill-fitting French window. It had the prolonged screech of a banshee as its icy fingers searched for any weak spot to wreak its havoc. The Shamal (meaning ‘wind’) is generated when low pressure mixes cool air from Europe and warm dry air from the deserts of North Africa to create a storm front. The resultant dry wind is funnelled between the mountains of Turkey and Iran and the high Saudi Plateau and it roars down through Baghdad. One of the by-products of the Shamal is the sandstorms or turabs that whip up the desert sands around Baghdad. During this period the observers braved the sandstorms and returned with stories of swirling sand inches deep on the main highways out of Baghdad. The Shamal was the wind that frightened Lawrence of Arabia’s Arab allies as they lay in the castle in Azraq in the spring of 1917. The Arabs warriors there were convinced that they were surrounded by devils as it howled like a banshee gusting through the stone crevices of the castle. Sandstorms are usually massive affairs and frequently cover an area the size of Iraq.

Over the next few days I had an opportunity to meet the rest of the staff. First, I met the drivers, with whom I would spend many hours travelling across Baghdad and to and from the north. In addition to Ayad there was Mohammed A. Al-Khaldi who had been a ship’s engineer before the war but was then penniless as all his savings that were in a Scottish Bank were frozen as part of the Sanctions process. On his days off he took me to various places around the city including the Mar Yousif (St. Joseph’s) Chaldean Catholic Church, off the Karrada, which was the main shopping area and just down the street from the Hotel Babylon. Mohammed showed me the gold, leather and copper and book markets and how to get to them on my own.

I was impressed that there appeared to be complete religious tolerance and freedom in Iraq. Islamic fundamentalists now hold sway and terrorise other religious groupings. A Catholic church was bombed recently and subsequently attacked by fundamentalists. Many of the congregation were killed including two priests over the four-hour attack. Even though it occurred in the centre of Baghdad it took security forces many hours to reach the massacre site.

Mar Yousif (Saint Joseph Chaldean Church Baghdad).

Photo: By kind permission of Bassam Haddad, Assistant Professor, Department of Public and International Affairs, George Mason University Fairfax USA, from the film ‘About Baghdad’ by Incounter Productions.

The third driver was Mohammed H. Rasheed. He had very little English and had a brother in the Mukhabarat. He showed me where to obtain beer and arak (a type of Iraqi ouzo) on the route back to the hotel. I also became very familiar with Abdalla Odeh’s driver, Saad. He was a tall swarthy handsome man and built in proportion. On one occasion as he was driving Odeh to his home in Amman their Volvo overturned on the desert road at over 100mph. Both men emerged with only minor injuries, surely a testimonial to the Volvo’s safety standards. Shortly afterwards Saad was arrested at his home during a dawn raid by the Mukhabarat. Knowing what such an arrest entailed and that the entire family could be incarcerated his wife lost her mind and his son went into some sort of catatonic paralysis. It was rumoured that Saad was suspected of smuggling during his frequent trips to Amman with Odeh. If so, he finally paid a very, very heavy price. Dr Ayad Humayde informed me recently that Saad was released in late 1999 and lost no time in fleeing the country immediately after.

One day one of the nationals offered to take me to some friends of his who claimed that they looted the Emir’s palace in Kuwait during the war there and wanted to offload some artefacts for a few hundred dollars. The artefacts in question consisted of a painting by Picasso allegedly given to the Emir on his marriage by the British Royal family and a pair of jewel-encrusted daggers allegedly given by Lord Louis Mountbatten on the same occasion. I was naturally very curious and was eager to see the merchandise. It seemed like a plot from a gangster film so a meeting was arranged with the sellers in the Hotel Babylon but due to an unexpected work commitment I could not make it. I told a friend about the incident and he took my place. He was shown a picture of the alleged painting and made some enquiries of the Museo Picasso in Malaga but they had no record of any missing Picasso fitting the description. So the scam artists were operating in Saddam’s Baghdad despite his arbitrary justice. Incidentally an alleged Picasso named The Naked Woman, reputedly stolen from the National Museum of Kuwait, is presently doing the rounds in the Art world but has been disowned by the Louvre.

Over the next few days I became aware of the relatively large number of professors and physicists working in the building. Imad Khaduri, who had been a divisional head in Saddam’s Nuclear Bomb Programme was the most prominent. The poor man was caught between a rock and a hard place. His wife had escaped Iraq and was teaching in Amman while he was living in Baghdad with his two young daughters Yamama and Nofa and son Tammam. Saddam would not let him out of the country, no doubt because of the secrets he carried. Every six months Imad would apply for an exit visa. Each time it would end up on Saddam’s desk and each time it was refused. Saddam was also caught between a rock and a hard place. On one side he had to persuade the Americans that he had no Weapons of Mass Destruction while at the same time give the Iranians the impression that he had such weapons. His military was severely weakened from the Sanctions regime and he feared an Iranian attack if they knew the truth. Imad never spoke unfavourably of Saddam: “The President must decide,” he would say. He used to confide in me and I believe in my predecessor, Tom Brosnan, and we provided him with oodles of sympathy but unfortunately nothing else. As a result he was very partial to the Irish and said that our understanding was due to our sad history

Later on I met S K Murthy who was appointed the Sector Operations Manager. Murthy, a graduate mechanical engineer, had been a Colonel in the Engineering Corps of the Indian Army. I grew friendly with him while in Baghdad and for a while took an apartment near his. He was on very good terms with the Indian diplomats in the Indian Commissioner’s office in Baghdad and I attended many dinners with them in Murthy’s apartment where he lived with his wife, a UN career lady. We spent many an evening discussing the Eastern philosophies and the Christian religions and Murthy was well-versed in both. In fact, we both looked forward to these discussions. He told me that Indian couples arranging to get married always went to an astrologer who gave them an account of their predicted future life together. These predictions he assured me were usually very accurate and unusually so in his case.

Murthy had taken part in military operations against Pakistan in Kashmir. He stated that the elevation they were fighting at necessitated that the soldiers rations should supply about 8,000 calories daily to each man. The mountain roads were treacherous and it was not uncommon for the military trucks to go over the edge and plunge hundreds of feet down taking their complement of soldiers with them. “We did not attempt to go down after them” he said, “as it would be futile”. This experience probably conditioned his response to some safety issues we had later.

For the first few days I explored the area around the office at lunchtime looking for some place to eat. As it was still Ramadan only a few cafes were open and to protect the practising Moslems from the sight of infidels eating food by day during the holy month, a large sheet was usually hung across the eating area. So I had my lonely repast skulking out of sight behind the sheet while everyone else on the street outside fasted. In time, I located a very pleasant restaurant up the laneway from the Sadoun Building and feasted there on steak in pepper sauce for the remainder of my time in Baghdad.

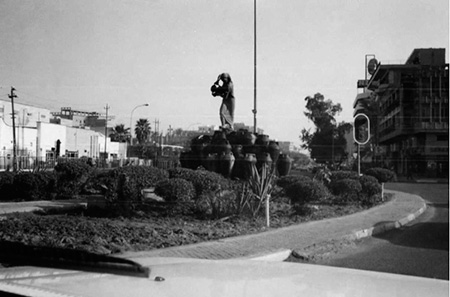

The return journey to the hotel in the evening was by a route parallel to Abu Nuwas Street. We swung into Sadoun Street with its statue of Abdul Muhsin Al Sadoun who gave his name to the Street and the Sadoun Building. He came from Iraqi aristocracy and attained high rank in the Ottoman Army taking part in many battles against the English General Maude who captured Baghdad in the First World War. A bitter opponent of the British Mandate of Iraq, he became Prime Minister four times, in 1922, 1925, 1928 and 1929. He fought strenuously against the British demands for de facto control of Iraq and reputedly committed suicide in 1929. I say reputedly as the body when found had two bullet wounds to the head. When he died the common people subscribed to have his statue erected here. His statue was the only one in Baghdad not damaged during the allied invasion and its aftermath.

Statue of Abdul Muhsin Al Sadoun in Sadoun Street.

Photo: By kind permission of Bassam Haddad, Assistant Professor, Department of Public and International Affairs, George Mason University Fairfax USA, from the film ‘About Baghdad’ by Incounter Productions.

We continued on to the roundabout at Firdos Square, the location of Saddam’s famous statue, publicly toppled by US soldiers during the invasion of Baghdad, and the 14th of Ramadan Mosque. The 14th of Ramadan is the Arabic date that an agreement was signed between Britain and Iraq in the person of Abdul Muhsin Al Sadoun. The delay in its ratification was the reason that Sadoun is alleged to have taken his own life.

The Statue of Saddam has been replaced by a modern sculpture by local artists that was placed on Saddam’s plinth with graffiti that proclaims ‘All donne go Home’ testifying to the human condition of ingratitude.

We drove straight through the roundabout and continued on to the next one with the Ali Baba statuary group and straight through on to the Karrada which is the Grafton Street or Regent Street of Baghdad. The Ali Baba statuary group featuring Kahramanain filling the jars and so killing the 40 Thieves is also the work of the sculptor Mohamed Ghani Hikmat. The prohibition on photography meant that I could only snatch the odd photo from my hotel room or a furtive snap from a UN vehicle.

The ‘Ali Baba’ statue, where Kahramanain, Ali Baba’s maid, is shown filling the jars, containing the 40 thieves, with oil.

The Karrada runs parallel to the Tigris and on into Abu Nuwas Street. It is awash with jewellery shops that sold gold and silver items as well as pearls from the Gulf. Watches of all the leading world brands graced their shelves. They also sold second hand items whose owners literally had to part with everything they owned in order to survive in the sanctions regime. One beautiful chandelier occupied the entire space of a large antique shop window and proclaimed the disintegration of a rich society. There were also high class establishments specialising in all the designer gear and others that displayed exquisite Persian rugs. When we reached the end of the Karrada we swung right into the Babylon Hotel.