3

The Skirmish at Tongue River Heights

“The campaign promises to be an important one. An old forty-niner of California, and one who has for nineteen years been mining in Colorado and the [Black] Hills, said yesterday that there were at least 30,000 Indians between the Big Horn and Black Hills ranges, and unless the whites took care they would likely be beaten.”—Dispatch from Fort D. A. Russell, Wyoming Territory, May 20, 1876, New York Daily Graphic, May 25, 1876

“We are at the threshold of a great struggle, and although it is out of any one's power to avert it now, a false impression as to its leading causes should not be suffered to remain. That ‘Injuns is pisen’ [poison] may be an excuse for all that is done to the Sioux, but history will not give much credit to excuses that are selfishness; for where the red man takes a scalp the white man takes the land.”—Editorial, “The Hostile Sioux,” New York Herald, May 29, 1876

“The campaign…against the Sioux originated in the refusal of that nation to leave their camps on the Big Horn and Tongue rivers, in the valley of the Yellowstone, and enter upon a reservation which the Government had set apart for them. After the Sioux leader, Sitting Bull, had scornfully disregarded the orders of the Government, troops were directed to enter the country and to expel the Indians.”—Editorial, “End of the Campaign,” New York Tribune, September 18, 1876

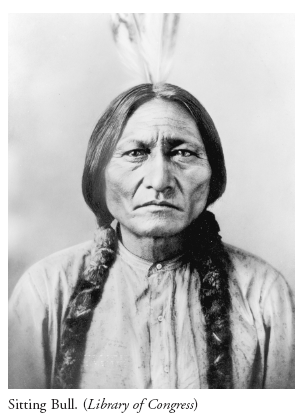

Following the battle of Powder River, the Cheyennes, destitute, set out to find the winter village of Crazy Horse. Realizing there was safety in numbers, the combined tribes—Crazy Horse's Oglalas and Old Bear's Cheyennes—sought a union with Sitting Bull's Hunkpapas.1 Sitting Bull was a well known “spiritual leader” whose “distinguishing characteristic” was “unrelenting hostility to the white race”; he never acquiesced to the whites, signed a treaty, lived on a reservation, or put his hand out for government rations. This was the beginning of a temporary alliance in which the tribes would travel together for mutual security.2 As winter gave way to spring, the alliance would attract additional support from other roving bands of Sioux, such as the Sans Arcs and Minneconjous, not to mention the summer roamers.

General Crook's column returned to Fort Fetterman on March 26, nine days after the lackluster partial victory over the Cheyennes and Sioux at Powder River. Writing one day after the fight, correspondent Robert Strahorn was quick to point out why he believed the attack had been botched.3 However, by the time of his next dispatch from old Fort Reno on March 22, he surprisingly shied away from any critical comments: “Over one hundred large tepees, with the accumulations of years in the shape of arms, ammunition, clothing, robes, blankets and cooking utensils, and tons of fresh and dried meat, were reduced to ashes. This reduced the foe to absolute want, and rendered his demoralization all the more complete from the fact that it took place in the heart of his own country, far from any supply post, and with most vigorous winter weather upon him.”4

Several lines later he added: “The soldiers displayed great fortitude and gallantry; especially the Egan Grays, consisting of forty-seven men under the command of Captain James Egan, who charged through the Indian village, and for a time withstood the entire fire of the enemy poured in from the cover of underbrush and rocks on all sides.”5

The most negative comment he had was about the weather, which had been “extremely disagreeable during the entire campaign.” Indeed, the temperature had invariably been well below zero, accompanied by the usual hazards and discomforts of icy conditions.

Be that as it may, it could not be denied that because of Reynolds's hasty withdrawal from the village, four dead troopers had been left behind.6 Even worse, if true, was the accusation that a wounded trooper had been left behind to the mercies of the Indians, which would have been anything but tender.7 On top of that, he torched the food supplies, against Crook's wishes.8 With freezing temperatures and insufficient provisions, Crook gave up the idea of continuing on to the mouth of the Powder River, where he expected to find Sitting Bull.9 As Major Stanton expressed it:

Gen. Crook proposed to push boldly down the Powder River to its mouth, and attack Sitting Bull's band before the latter could possibly escape him. This would have ended the war, and prevented the necessity of sending other expeditions. Col. Reynolds neglected to obey [Crook's instructions]…and burned, destroyed, and left enough meat there to have fully enabled Gen. Crook to carry out the plan of the campaign. But with this failure, and only partial rations for four days left, it was impossible to take the command further, and the only thing left to do was to return to Reno.10

If that was not enough, the Cheyennes recaptured most of their horses the morning after the fight, a detail that certainly reflected negatively on the ranking officer.11 With Crook turning back to Fort Reno to regroup, Sheridan's plans for a winter conquest over the recalcitrant and defiant Sioux and Cheyennes were dashed.

Dashed, too, were the military careers of two officers: Colonel Reynolds and Captain Moore. Crook preferred courts-martial charges against them for “misbehavior before the enemy.”12 The trials took place in January 1877, and both men were found guilty. Reynolds was suspended from rank and command for one year. Moore was sentenced to suspension from command for six months and confinement to his post, Fort Laramie. President Grant remitted both sentences in honor of their past service, but neither man fared well afterward. Reynolds retired on June 25, 1877, and Moore resigned his commission on August 10, 1879.13 A third officer, Captain Noyes, was also court-martialed, the charges filed by Reynolds being for “conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline.” Holding the captured horse herd a short distance from the village, Noyes had allowed his company to unsaddle their tired mounts while the men made coffee. With the results of the fight being less than expected, it just did not look good. The trial took place in late April 1876. Though found guilty, Crook let him off easy, stating it was punishment enough that he was censured by his fellow officers, essentially chalking the incident up to an “error in judgment.”14 Noyes was back in action with the Second Cavalry in time for Crook's spring-summer campaign.

And this new campaign was to be quite different than its predecessor. Instead of just one column in the field, there would be three. As one correspondent explained: “There is a sort of anaconda combination planning for the purpose of crushing Sitting Bull, Gen. Crook's troops forming this part of the circle. The troops of Gen. Terry and Col. [John] Gibbon15 are already under way from Minnesota [Dakota Territory]16 and Montana.…The movement of the troops of Gen. Terry and Col. Gibbon, it is expected, will drive the Indians into the grasp of Gen. Crook's troops.”17

This strangulation-style strategy, as devised by Sheridan, was the same used against the Southern Plains tribes in 1868–69 and 1874–75. It was a simple idea that had worked effectively in the past. Three or more army columns would converge upon a common area, making it difficult for the Indians to escape.18 As Sherman expressed it, “We conquered the Kiowas and the Comanches in the same way. We hemmed them in and caught them by finding their camps.”19 If the Indians evaded one column, they were bound to run into another. As applied to the current campaign, if the Sioux and Cheyennes somehow avoided one or all of the army columns, there were not too many options available; continuously hard pressed with no time to replenish food stores, they could either escape to Canada or sue for peace and surrender at the agencies.20 The biggest problem for the army was coordination among the columns, and, consequently, much was left to chance. That is why it was important that each column be relatively strong enough to fend for itself.

In this new campaign, Sheridan's strategy called for three simultaneous columns. General Crook would advance from Fort Fetterman, Wyoming Territory, in the south; General Terry from Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, in the east; and Colonel Gibbon, Seventh Infantry, from Forts Shaw and Ellis, Montana Territory, in the west. Gibbon's column, operating under Terry's orders, was the smallest of the three units, and therefore more of a “supporting force.”21 The region they were to converge upon was west of the Great Sioux Reservation, south of the Yellowstone and east of the Big Horn Mountains, including the valleys of the Powder, Tongue, Rosebud, and Big Horn rivers. On May 29, Sheridan wrote a letter to Sherman, explaining his loosely styled strategy and how he envisioned it would play out in the military campaign that was just then getting under way:

As no very accurate information can be obtained as to the location of hostile Indians, and as there would be no telling how long they would stay at any one place, if it was known, I have given no instructions to Generals Crook or Terry, preferring that they should do the best they can under the circumstances, and under what they may develop, as I think it would be unwise to make any combinations in such a country as they will have to operate in.22 As hostile Indians, in any great numbers, cannot keep the field as a body for a week, or at most ten days, I therefore consider—and so do Terry and Crook—that each column will be able to take care of itself, and of chastising the Indians, should it have the opportunity.

The organization of these commands and what they expect to accomplish has been as yet left to the department commanders. I presume that the following will occur:

General Terry will drive the Indians toward the Big Horn Valley, and General Crook will drive them back toward Terry; Colonel Gibbon moving down on the north side of the Yellowstone to intercept, if possible, such as may want to go north of the Missouri to the Milk River.23

It sounded good on paper. It should have worked. In most cases it probably would have worked. But this year proved to be different.

Generals Crook and Terry fronted the two primary commands. Crook had about 1,000 men and Terry about 930. Colonel Gibbon led about 425, including 196 cavalry. That's a fighting force close to 2,350 men, including some 1,770 cavalry.24 During the winter of 1875–76, the nontreaty Indians were thought to number between eight hundred and one thousand fighting men.25 Regardless of the accuracy of this estimate, their numbers had increased considerably as winter turned to spring. Based on newspaper reports between March and late July 1876, Sitting Bull's legions had grown to between two thousand and four thousand.26 One newspaper story in late May 1876 clearly illustrated the uncertainty regarding the number of “hostile” Indians, declaring one total, then changing it in the very next sentence:

In all there are of Cheyennes, Sioux and others, some 3,000 ready to fight out this campaign against Gen. Crook. They have numerous allies, and well-informed people place the actual hostile Indian camp at from 7,000 to 8,000 first-class fighting men, armed with the best rifles and plentifully supplied with ammunition furnished by post traders and speculators who grow rich on helping to shed the blood of the regular army.…They are commanded by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse [who are] eager to signalize themselves by slaughtering the whites.27

Despite the planned three-pronged assault, one reporter was not too optimistic about the upcoming expedition. Recognizing the inherent difficulty of trying to find the Indians during the warmer months, he wrote:

From June until October they will wander from pasture to pasture and hunting ground to hunting ground, and the probability of entrapping them again into a fair engagement is very faint. The fruit of the present enterprise, therefore, is more likely to be the ashes of wasted gunpowder alone than anything else, while the Sioux may stealthily add many scalps to their blood encrusted trophies.28

As Reuben Davenport (now about twenty-four) documented, many on the frontier were unable to sympathize with a people that glorified in “blood encrusted trophies.” The fact is that the majority of westerners viewed the Indians as being less than human: “The men of the Territories and ultra-Missouri States look upon the Indian, as he now exists on the plains of Dakotah and Wyoming, as human only in his strictly physical traits of form, anatomy and physiology. It is impossible, after having some experience of frontier life, not to join, partially at least, in this belief.”29

A Meeting with the Crows

New York Herald, Wednesday, May 3, 1876

Bozeman, Montana April 14, 1876

A council with the Crow Indians was held at their agency near the mouth of Stillwater on the 9th of April, and Colonel Gibbon called on the Crows to give him such aid as they could in subduing the Sioux. Chiefs claiming to represent 3,000 Crows were present at the council, and great excitement prevailed, many of the chiefs declaring it was the duty of the Crow Nation to aid the whites, who had always been their friends, against their ancient and inveterate enemies, the Sioux. The Crows asked time to consider, and it was believed most of the young men would go to war against the Sioux. Lately the Sioux have been hunting on the Crow reservation, and have killed several Crows. The Crows say they cannot hunt the buffalo on their own land for fear of the Sioux, and only a few weeks ago asked the whites to come and help them drive the enemy beyond the Yellowstone. All the Big and Little Horn country is included in the Crow reservation, and game is plenty near the mouth of the Big Horn River, but the Sioux occupied the country and the Crows could not hunt. The Sioux have whipped the Crows so often that they were completely cowed, but the troops coming into the country have put a new spirit in them, and it is believed they will seize upon this opportunity to revenge themselves upon the Sioux for past injuries.

One frontiersman explained to the Herald correspondent the opinion held by many on the frontier that the romantic version of the Indian was far from the reality:

People who have not personally become acquainted with the Sioux, Arapahoe or Cheyenne races may be amused by romances setting forth the nobility of the red man as he appears in the classic literature of the past 300 years, but they have very dim ideas of the animal in his real state.…The mould of man is only a disguise [for the Indian].…Vengeance being his creed, a process of extermination to be enforced so long as he remains unsubjected would be justifiable.30

To Davenport's credit, he did not entirely buy what the man was selling (although he was not above referring to the Sioux as savages in his dispatches), and acknowledged that the views expressed were likely the result of ulterior motives:

The view of the situation on this frontier just reproduced illustrates much of the public sentiment. The horror of the Sioux, however, in my opinion, is exaggerated. It is noticeable that those who express it most strongly are those “honest” miners who have been most eager to invade the Black Hills.31

On the road from Cheyenne to Fort Fetterman, Davenport observed that dejected parties of miners were leaving the Black Hills, at the same time capturing for posterity a sample of the wordplay then in vogue:

They are returning to civilization in swarms, panic stricken by the crack of Indian rifles and disgusted with fortune.…When asked, “Did you find any gold?” the reply usually was of the purport, “Yes, but a darned sight too many Indians.”

Some satirical “boy in blue” in repartee applied to them the contemptuous sobriquet which they had previously freely bestowed on Eastern men who have been attracted hither by the rumor of gold. “So you've turned tender-feet, ‘ave ya? Don't like the Black ’ills ’swell's ye did, do ye?”32

A few days later, at Fort Fetterman, he learned from a man named Murphy that the people occupying Custer City, in the Black Hills, “live in constant terror; all who can are abandoning the country.”33

On May 16, General Crook visited the Red Cloud Agency hoping to acquire scouts for the forthcoming campaign, but the trip did not go as planned due to the interference of agency officials. Davenport sarcastically noted: “The Indian agents have prevented the Sioux from joining General Crook, but they do not seem to be able to restrain them from joining the bands now engaged in hostilities.”34

To back up that claim, the same report declared that one thousand agency Sioux were then on their way to join Sitting Bull. In fact, reports of Indians leaving their reservation to join the “hostiles” had become quite commonplace during spring 1876.

According to Davenport, Red Cloud also gave Crook a warning:

The Gray Fox [Crook] must understand that the Dakotas, and especially the Ogallalas, have many warriors, many guns and ponies. They are brave and ready to fight for their country. They are not afraid of the soldiers nor of their chief. Many braves are ready to meet them. Every lodge will send its young men, and they all will say of the Great Father's dogs, “Let them come!”35

For Crook, the day almost turned out to be his last. About four or five warriors from the agency had planned to ambush him on the road back to Fort Laramie, but when the general's military escort turned out to be stronger than expected, they turned their deadly attention to a local mail carrier named Charles Clark. A telegram out of Fort Laramie on May 17 reported the unfortunate incident:

General Crook narrowly escaped an ambuscade on his return to this post. When he reached a point fifteen miles this side of Red Cloud, he met Charles Clark, the stage driver and mail carrier. The latter proceeded toward the agency, and when within ten miles of there, a war party, which had been lying in ambuscade, attacked and killed him, took the four horses he had been driving and decamped, leaving the body, stage, and mails on the road. The corpse and mail were taken to Camp Robinson today by a detachment of troops sent out by the commanding officer. Clark was one of the best men in the employ of the stage company. He had been tending stock here, and this was his first trip with the mails, he having taken the place [of the former mail carrier] of his own accord and because his predecessor had refused to again carry the mail through, being afraid of the Indians.36

That Crook had indeed been the target was confirmed shortly afterward by a Sioux named Rocky Bear.37 Not able to secure the services of Red Cloud's followers, Crook now turned his attention to enlisting the Crows and Shoshones, both tribes being hereditary enemies of the Sioux. “This plan of making Indians fight Indians,” a correspondent was to record in May 1877, “is the keystone of the wonderful success General Crook has met with in his management of the wild tribes.”38

Shortly thereafter it was arranged that three hundred Crow Indians would join the command at the ruins of Fort Reno on the Powder River, ninety miles north of Fort Fetterman, on May 30.39 Lieutenant Bourke considered the Crow scouts to be “equal to that of an additional Regiment,”40 but high water was making the North Platte difficult to cross,41 on top of which the ferry boat cable snapped several times,42 and Crook, knowing he would not be able to make the rendezvous on time, was concerned that the Crows would not wait for him. On May 27, Davenport wrote from Fort Fetterman: “[It] is feared that the Crows will disperse when they do not find the army at the trysting place. General Crook has, therefore, ordered two companies of the Third Cavalry, commanded by Captain [Frederick] Van Vliet and Lieutenant [Emmet] Crawford, to set out today with supplies for eight days to meet the Indian allies, and remain in camp with them until the coming up of the main force.”43

On May 29, for the second time in three months, Crook departed Fort Fetterman at the head of a large military command, once again moving north along the Bozeman Trail. This time his force, officially named the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition, consisted of ten companies of the Third Cavalry, five companies of the Second Cavalry, three companies of the Ninth Infantry, and two companies of the Fourth Infantry. In all, there were about 825 cavalry, 185 infantry, some 200 “well-armed” teamsters and packers, 100 wagons (pulled by six mules each), and about 320 pack mules, not to mention enough ammunition to wipe out the Sioux nation several times over.44 As laid out in General Orders No. 1, May 28, Lieutenant Colonel William B. Royall, Third Cavalry, was placed in charge of the cavalry, and Major Alexander Chambers, Fourth Infantry, was given command of the infantry.45 Royall, previously in the Fifth Cavalry, had served with Crook in Arizona against the Apaches, and was “an officer of acknowledged courage and judgment,” while Chambers had “studied the Indian for years on the frontier, and brings excellent executive ability to the aid of a thorough education in the art of frontier war-fare.”46 Civilian Tom Moore, who was with Crook during the winter campaign, was back as chief packer.47

With Crook transferred to the Department of the Platte from Arizona in April 1875, hopes were running high in the nation's capital and on the frontier that he would be able to duplicate his success against the Apaches by subduing the Sioux and Cheyennes. The consensus on the frontier was that relations between the government and the Sioux had

reached at last the crisis which military men on the frontiers of Nebraska, Dakota and Wyoming have predicted so long.…[Crook's] ability in warfare with the Indians has been so well demonstrated in the country of the Apaches…that it needs no eulogy. In the War Office it is held in high esteem and has caused the giving to him of the task of reducing to submission the wild bands of the Sioux. No brigadier in the army could have inspired the people of this department with more confidence in the efficacy of his protecting power. His intention of fully exerting it is determined. The measures to that end are to be offensive as well as defensive until the enemy of the miner and settler shall have recognized the futility of further attempts at aggression and independence.48

According to Strahorn, Crook was planning for “brisk operation[s] during the entire summer, if necessary.”49

[The] cavalry and pack trains will be pushing into any region of country an Indian can and does penetrate. Returning to the supply camp when supplies give out, the sallies will continue to be made as often as necessary. General Crook sets no date upon which to return, but quietly says he wishes to stay out until he can once and forever settle the Sioux problem. How long this will take is little more than a matter of conjecture, although it is generally believed that the entire summer will be required.50

Strange to say, but some of the people Strahorn met while on the trip to Fort Fetterman thought a summer campaign against the Sioux actually sounded like fun: “Interested friends at the different forts…usually said, ‘Oh, you will have a holiday trip this summer. So different from our last winter's campaign, you know, nice warm days and pleasant nights. Really I wouldn't mind going along myself.'”51

The first day's march was a short one, and the command camped for the night at Sage Creek, about twelve miles northwest of Fort Fetterman. The next day it reached the south fork of the Cheyenne River where, as one officer jokingly noted, Crook's “last expedition issued all their fresh beef to Sitting Bull.”52 Three days later, on June 2, Crook's force arrived at the ruins of old Fort Reno; it found Van Vliet and Crawford, but no Crows, and no sign of the Sioux. Wasting no time, Crook dispatched his three main guides, Grouard, Richard,53 and Pourier on an important mission: [They were to go] “north to the Big Horn River, 150 miles distant, to meet the Crows there, or to swim the stream and go on to their agency if unsuccessful in finding them sooner. The brave scouts started at night, and expected to make the ride from the Powder [River] to Big Horn Cañon and back to Fort Kearney in seven or eight days.”54

Five days later, the command made camp at the junction of Prairie Dog Creek and Tongue River, deep in enemy territory, about 190 miles, as the crow flies, from Fort Fetterman. Late that night, they received a visit from “a solitary Sioux [who] came to the top of a neighboring bluff and created no little amusement by asking impertinent questions and hurling braggadocio at our devoted heads in true savage style. One of our men who speaks the Sioux tongue kept up a conversation with him for some time, but nothing satisfactory was elicited.”55

Also on June 7, the command laid to rest its first fatality, Private Francis Tierney, Third Cavalry. Tierney had accidentally shot himself with his revolver on May 30, “the ball entering his thigh and passing upward into the abdomen, inflicting a mortal wound.” He died the night of June 6, after “great suffering.”56 The same day Tierney died, Sergeant Andrew J. O'Leary, Ninth Infantry, broke his arm when an ambulance tipped over.57 Such was life on an Indian campaign.

Although Grouard, Richard, and Pourier were not due back for another day or two, Strahorn no doubt spoke for Crook when he wrote: “Their return is looked for with unfeigned anxiety, as well it may be. Without the Crows or some other trusty Indian scouts to follow the Sioux—on the principle that it ‘takes a thief to catch a thief’—there must be much bewilderment and unnecessary traveling to find the savages in their own haunts.”58

Unless, of course, they found the troops first. Now we turn to four exciting narratives about the skirmish at Tongue River Heights, June 9, 1876, just south of the Montana line. Two of the reports are from correspondent Joe Wasson59 (who had previously accompanied Crook on his 1867 campaign against the Paiute Indians in Oregon), one is from Reuben Davenport, the New York Herald correspondent, whose dispatches were soon to take aim at General Crook as if they were fired from a Sioux rifle, and lastly, there is a little-known account by Charles St. George Stanley, the mysterious artist-correspondent for Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.60

Daily Alta California (San Francisco), Thursday, July 6, 1876

GEN. CROOK'S EXPEDITION.

THE BIG HORN AND YELLOWSTONE COUNTRY—THE ROUTE FROM FORT FETTERMAN TO THE SCENE OF THE LATE ENGAGEMENT—OUR CORRESPONDENT'S DESCRIPTION OF THE FIRST BRUSH WITH THE INDIANS.

[Written by Joe Wasson]

In Camp, Forks Tongue River and Prairie Dog Creek, Wyoming Territory, June 9—I sent you a few items from Sage Creek, twelve miles this side of Fort Fetterman, May 30, since which time Crook's command has pulled along to this place, in the heart of the Indian country 187 miles, or 232 miles from the nearest point on the Union Pacific Railroad. As yet, not a hostile shot has been fired, though we have lost one man by accident; and of the 2,300 horses and mules, only nine have failed to connect since they left Cheyenne and Medicine Bow, and the general health of both men and beasts has been better than expected. Three or four cases of mumps and one of scarlet fever are all that have been reported among the soldiers or citizen employes. The weather has been cool and favorable for marching as a general thing. On the 30th of May, Francis A. Tierney, private in Co. B, Third Cavalry, accidentally shot himself with his revolver, and lived until the night before our arrival here (the 7th inst.), where he was buried about sundown with all the military honors possible. Captain [Guy V.] Henry [Third Cavalry] read the burial service, after which three volleys were fired over the grave; flat stones laid therein, his name inscribed, etc. He was a native of New York, aged twenty-eight years. It was something as impressive and lonely almost as a funeral at sea.

THE COUNTRY.

From Fort Fetterman, on the North Platte, to old Fort Reno, on Powder River, the distance is 90 miles; the road is an excellent natural one, over a rolling, grassy country. The water, at convenient distances, was too much tinctured with alkali to be very acceptable. The several little streams were headwaters of the Cheyenne and Powder rivers; one or two had considerable cottonwood timber adjacent. Deer, elk, antelope, sage hens, grouse, etc., added variety to the bill of fare. On the morning of June 1, there was a slight fall of snow to grace and purify the scene—and also cause the hair to fall. Fort Reno was located on the west bank of Powder River and was the first of a line of three posts, reaching through to the Big Horn River—Forts Kearney [Kearny], and C. F. Smith being the other two—all of which were abandoned under the Treaty of Laramie of 1868, and which treaty was the result of the celebrated Fetterman Massacre, in December 1866, at Kearney. These posts were all burned by the Indians after the treaty, and only the stone chimneys and desecrated graveyards remain to tell the sickening story. Powder River is over one hundred feet wide, three feet deep, and its bottom lands well timbered with cottonwood.

From the second day after leaving the Platte, the Big Horn range loomed up as majestic and bold as the Sierra Nevada, looking west from about Virginia City. It is called Big Horn because of the Indian name for mountain sheep. It is 150 miles long by 50 broad, and at least 50 miles of it is covered with snow, culminating in Cloud Peak. It is also heavily timbered, and is a powerful watershed to the east ward. Big Horn River is practically Wind River, and heads in the mountains to the westward. From Powder River north, our road crossed Crazy Woman's Creek, Clear Creek, Rock Creek and Piney [Creek]—on the latter was located old Fort Kearney. All these are excellent streams, coming out from under the road. From Reno to Kearney (63 miles), the road was closer to the Big Horn Range, over a magnificent grazing country. The mountains evidently contain more or less placer gold, and a party of 60 men, headed by John H. Graves, formerly of Diamond City, Montana, had just arrived from the Black Hills for the purpose of prospecting the Big Horn Range. Graves reports a few miles of good diggings on Dead Wood and White Wood creeks, in the northern part of the Black Hills, but no paying mines elsewhere to speak of. Custer City is merely hanging on by the eyebrows; it is not the Indians that are killing the place, but the want of paying ground. If the Big Horn Range does not contain a goodly breadth of paying deposits, outside appearances are very deceptive, to say nothing of the frequently reported good prospects. These mountains remind one very much of the Boise Basin Mountains of Idaho, and being on the line of the Montana diggings, gold will certainly be found—whether in paying quantities remains to be seen. I hope to be able to go over the ground myself, after taking a turn at Indian scouting.

MASSACRE HILL.

At old Kearney the long mound containing the remains of the Fetterman Massacre is yet plainly visible, and about three miles north of the post, on the road we traveled, the place where the affair occurred was pointed out. It is called Massacre Hill, a point to where the doomed party retreated, after seeing the trap laid for them. But their want of ammunition and breech-loading guns made it impossible for them to escape. Not a man of the ninety odd, including three citizens, but was literally shot or speared in cold blood. Capt. Fetterman, Lieutenants Brown and Greenwood,61 and the entire company of infantry, were piled up along the road and buried as before said. Colonel Carrington commanded the post and heard the firing, and it is said that he was prevented from going to the scene by his wife [Margaret], who has since died; and he has also married the widow Greenwood,62 who called him all sorts of names during the massacre. This is Richard the Third enacted over again on a small scale. I wish you would look up the Treaty of Laramie, and consider how often it has been brutally violated by the Indians, long before the Black Hills excitement. Had it been the English, or most any other but our tolerant Government, the Fetterman Massacre would have been avenged to the death of the last savage engaged therein. But it is as it is, and here we are, Mr. Merryman, as the circus has it, going over the ground in battle array, for the purpose of enforcing the so-called treaty aforesaid. The savages have had a soft thing under that idiotic stipulation.

It is to be hoped that the Black Hills and Big Horn expeditions of last year and this will compel the Government to gather in all the Sioux scalawags if it takes the entire U. S. army to do so. The Red Cloud and Spotted Tail agencies should be moved eastward to the Missouri River, and this vast and valuable country secured to civilization at once.

THE CAMP.

This camp is pleasantly situated on the south bank of Tongue River—the chief haunt of the hostile Sioux—at an elevation above the sea of 3,750 feet. Medicine Bow, on the Union Pacific Railroad, is 6,500 feet. There is quite a forest of cottonwood and box elder on the bottom land. The river is about 200 feet wide and three deep, and contains a variety of fish. The grazing is good, and there are plenty of buffalo, deer, etc., round about, and hostile Indians spying around, so that altogether the place is quite interesting. Until we reached here Indian “sign” was singularly scarce, but enough was visible to give us to know that we were continually watched, and the night after our arrival here63 a band of eight mounted Sioux came to the edge of the high bluff overlooking our camp from the north side of the river, and called out, asking various questions, regarding the Crow Indians and half-breeds, as if the former had come here direct from the Red Cloud Agency. You will remember that Crook sent to Montana for a band of Crow allies, and expected to meet them at old Fort Reno, but failing to connect he sent his three chief scouts on ahead to Montana to see about it. As yet we have not received any news from them, although it is now about time. Their services are in demand here, as a party of about twenty-five hostiles crossed the river last night just below Prairie Dog Creek, showing that we are watched in some force. But this morning the gratifying intelligence came in from Fetterman, in despatches for General Crook, to the effect that one hundred Snake [Shoshone] Indians were due at old Fort Kearney, 35 miles back, on yesterday, so that they may be expected in now every hour. They come from Fort Stambaugh, near the South Pass, on the Sweetwater River. Even should the Crows fail to appear at all, and the Snake allies come to hand all right, the command will soon leave here for the war path. A base of supply will be established at this or some other point on Tongue River, the wagons sent back to Fetterman for more rations, etc. The several companies of infantry will be detailed for these duties. The rest here is very refreshing, indeed. There is a general cleaning up of clothes, guns, etc., over-hauling of stock on hand, horses shod, etc.

FIRST HOSTILE DEMONSTRATION.

Saturday, June 10—Our camp on Tongue River was the scene of considerable variety of entertainment yesterday afternoon and evening. Before dinner we had two horse races and one foot race. Captain Burt's charger won the two former, and the poor animal had scarcely cooled off, when his left foreleg was broken by a bullet fired from the bluff north of the river, and heretofore described. The pickets on the receding bluffs, east of Prairie Dog Creek, sounded the alarm, which was soon followed by a raking, random volley from a party of well-mounted Indians, estimated all the way from 25 to 100, as seen from different stand-points. The distance from the edge of the bluff to the outer edge of camp is 500 to 700 yards, and the enemy's guns were of much longer range. The bullets “zipped” in among our tents, horses, and wagons, in a way extremely interesting. The soldiers, teamsters, etc., returned the fire at once; but General Crook put a stop to that as soon as possible, considering it a causeless waste of ammunition, and calculated to convey to the enemy a poor opinion of our coolness. Three companies of the Ninth Infantry—Captains Burroughs, Burt and Munson64—were sent across the creek to guard the approaches from the east, and four of the Third Cavalry—Captains Mills, Lawson, Sartorius and Andrews65—were ordered to ford the river and ascend the bluff. All this was done in good time and shape. The Indians, in the meantime, kept up their fire on our camp until the cavalry got within shooting distance, when they fell back into the higher hills and ravines, occasionally coming forward, circling about and returning the fire of the soldiers. It was a full hour and nearly dark before peace once more prevailed on Tongue River. It is singular that no more damage was done to camp, which is concentrated into a small space. At least three hundred shots were fired into it, and no man was seriously hurt; two cavalrymen were bruised by spent balls.66 One mule was fatally wounded, and besides Burt's, Lieutenant Robertson's67 horse was shot in the leg. One or two other animals were reported slightly hurt. There is no satisfactory evidence that the enemy was damaged in the least. He was very chary of his sacred person, except in one or two instances, where a bold warrior dashed to the edge of the bluff, presenting a tempting mark on the horizon. The marks of their long-range guns, as furnished by the government and agents, are here and there visible in tent-poles, wagon-beds, etc. Gen. Crook thinks this impudent demonstration in broad daylight was done for the purpose of covering the retreat of an entire village not far off, and regrets that his expected Indian allies were not on hand ere this to do scouting duty. As it is, we are in a state of suspense; we will probably have to move up or down the river for grass ere the arrival of either the Crows or Snakes. It is feared that the warrior element of the enemy will mostly cross the Yellowstone, and give much trouble to catch ere winter.

Jose.

New York Tribune,

Saturday, July 1, 1876

THE SIOUX WAR.

GEN. CROOK'S EXPEDITION.

AN ATTACK BY THE SIOUX.

[Written by Joe Wasson]

Camp on Tongue River, June 10—The expedition of Gen. Crook has remained in camp here for several days, waiting the arrival of the Crow and the Snake Indians, who will act as scouts. Yesterday afternoon the hostile Indians first made their appearance. The camp is surrounded by bluffs, bold or receding, and the pickets, wherever placed, are plainly visible from almost any point. About 6 p.m. those on the receding bluffs below the mouth of a creek, half a mile to the eastward, were seen firing in the air and making demonstrations to attract our attention. Scarcely had this occurred when firing commenced on a high bluff on the north side of the river, where no pickets were placed in the day time, and bullets began to “zip” overhead among the tents, horses, and wagons throughout the camp, and all hands soon realized that a party of hostile Indians had begun an attack. On the impulse of the moment the fire was returned from almost every portion of our side, but owing to the extreme distance—500 to 800 yards—to where the Indians were, Gen. Crook ordered all firing to cease, as it was a mere waste of ammunition. The pickets having discovered the Indians, unexpectedly so the latter, prevented the sneaking wretches from doing more than fire at random. They were mounted, and some of them rode up to the edge of the bluff in very plain sight for an instant, only to turn and fall back out of range, on the whole, it must be said, affording a very pretty sight. In the mean time three companies of the 9th Infantry, C, H, and G, Capts. Munson, Burt, and Burroughs, with Lieuts. Capron,68 Robertson, and Carpenter,69 were formed under the fire and hurried across the creek to guard the approaches from the east, while Col. Royall of the 3d Cavalry dispatched companies M, A, E and I of his regiment across the river to engage the enemy or drive them away. The water came up to the horses’ flanks, but all were over and up the bluff in short order. Perhaps 100 shots were exchanged between the cavalry and the Indians, but at too long range to effect anything serious. The Indians would keep falling back and circling round in such fashion that it was useless to follow them, especially so late in the evening.

The firing altogether lasted about one hour—from 6 to 7 o'clock p.m. The casualties and injuries sustained on our side were few and almost unworthy of mention considering the number of shots fired into the camp—at least 250. Two cavalrymen were slightly wounded by spent balls. Gen. Crook thinks the enemy consisted of the inhabitants of a single village, and the object of their attack was to cover their change of camp.

New York Herald,

Friday, June 16, 1876

AN INDIAN BATTLE.

THE WARRING SIOUX ATTACK GENERAL CROOK'S COMMAND.

TONGUE RIVER CAMP SURPRISED AT MIDNIGHT.

A SHARP FUSILLADE.

CHARGING THE RED ENEMY FROM A DANGEROUS POSITION.

[Written by Reuben B. Davenport]

General Crook's Big Horn Expedition, Camp on Goose Creek, June 11, via Fort Fetterman, June 15.

This body of troops had marched 190 consecutive miles on [through] June 7, when Tongue River was reached, and then they rested three days. Until then no unequivocal signs of Indians had been seen, although puffs of smoke rose above the eastern horizon. Part of these signals were made by a party of miners from Montana, who were examining gulches in search of gold near Pumpkin Butte and removing toward the Black Hills. Their recent camping grounds were found, where they had erected redoubts for defense against Indians, with whom they had probably had skirmishes.

DUSKY WARRIORS ELOQUENT AT A DISTANCE.

On the night of our arrival at Tongue River Camp [June 7] we were aroused at twelve o'clock by a loud declamation delivered by a sombre figure walking on the top of the bluffs on the north bank, opposite General Crook's headquarters. Other figures from time to time appeared and harangued successively during an hour. As nearly as could be comprehended, they announced the destruction of the invading force if not withdrawn, and warned us of a formidable attack before two suns should roll around. They asked us, as if in irony,

IF THE CROWS HAD JOINED

the troops; and now some fear is felt lest harm may have come to the guides70 sent to Montana Agency [Crow Agency] to gain their alliance, who have not yet returned. After this visitation the camp was strongly picketed, but a day and night succeeded the savage menaces with only a slight false alarm. The day before yesterday, at about four o'clock in the afternoon, the infantry picket saw about fifty Indians on the bluff opposite the camp, stealing to positions behind the rocks.

THE INFANTRY FIRED

upon them and the camp was alarmed. Though surprised they immediately returned the fire with yells. A hundred flashes were instantly seen along the crest of the ridge, and several mounted warriors rode out in full view, circling rapidly, and there was instantly heard another sharp fusillade. A volley from the camp was poured into the bluff. The pickets on every side were strengthened and the herd secured, in anticipation of any attempt that might be made to capture it. Half a mile up the river

A BAND OF SIOUX

tried to cross, but were driven back by the prompt attention of the pickets. Indians were seen at the same time on the south side of the camp, but they remained distant. A battalion, under the command of Captain Mills, Third Cavalry, advanced rapidly across the river, dismounted in a grove under the bluff and charged up the deep ravine. The first man to reach the top saw

TWO HUNDRED INDIANS,

moving incessantly on ponies, but slowly receding. The troops, stretching out in a skirmish line, drove them back in the face of a brisk fire, which they answered wherever the redskins were visible above the sagebrush, behind which they sought to screen themselves. They seemed bold and confident, and when a feint of retiring was executed by the troops they quickly changed their retreat to an advance. It is supposed they had a large reserve massed in the ravines and expected to entice the small party into a pursuit, so as to

SURROUND AND ANNIHILATE THEM.

When they saw the full strength of the cavalry they finally retreated. One of the party of Indians, on attempting to cross the river, was shot, and was lifted from his seat by his companions. Those on the bluff led off the riderless pony.

It was supposed that two Indians were wounded or killed, at least. No soldier engaged in the fight was injured, but two in the camp suffered contusions from spent balls. Three horses and one mule were killed.

SHOSHONE AUXILIARIES.

Intelligence has been received by our commander of the probable coming of 120 Shoshones as auxiliaries, under Washakie, the chief. Their arrival is expected every day, and active aggressive operations only await the coming of these Indian allies.

THREE THOUSAND MORE WARRIORS PAINTED.

General Crook is informed that 3,000 more warriors have deserted the Red Cloud Agency, proceeding north on the warpath. It will probably be his policy to prevent them finding refuge there again if whipped, until they sue for peace and surrender their arms. The presence of the Fifth Cavalry there is to enforce this plan.

In consequence of the unsafe position of the camp on Tongue River the expedition marched today sixteen miles to this point, which will be made the base of supplies. The Herald courier with this despatch makes a most perilous journey through a region alive with Sioux guerillas.71

Colorado Miner (Georgetown),

Saturday, June 15, 1878

[Written by Charles St. George Stanley]72

Returning to camp [June 9], I found that a horse race was upon the tapis, and turned aside to witness it. Of course it was not perhaps as au fait [up to the standard] as the affairs at Jerome Park, or the Derby, don't you know? but still we enjoyed it. After the horse race, the packers got up a foot race and this athletic exhibition was witnessed by a large portion of the command. Returning slowly to our tents I noticed that the clouds hanging in the west began to assume all the beautiful tints of a glorious sunset, a thing of almost daily occurrence.

Supper was ready and we arranged ourselves around the mess table, with the frugal meal (beans and bacon) before us. Jokes were cracked and we were merry with strophe and antistrophe of conversation, when a sharp report broke upon the evening air, followed by the vengeful hiss of a bullet. Then another and another report and finally a regular volley. “Indians!” was the cry and away we dashed to secure our weapons. It was some time before order was brought out of the confusion, and then along the whole line the rattle of musketry told that the enemy were being answered. The firing by this time had become so general across the river, and the passage of bullets so rapid, that the air seemed alive with bees as the leaden hail whizzed over and around us.

Volley answered volley and the evening breeze drifted clouds of smoke redolent of powder through the trees. The yelling of the savages was something horrible, and the wild, painted forms of the Dakotas, darting here and there upon the bluffs opposite, firing at every plunge of their ponies, gave the scene a sinister appearance. One warrior in particular, attracted attention. He was mounted upon a white war pony, smeared with great bands of vermillion, and his head adorned with a coffee pot, brightly burnished and decorated with eagle plumes. This individual rejoiced in the sobriquet of “The man with the Tin Hat,” and it was his business to pass rapidly backwards and forwards upon the side of the ridge, in order to draw the fire of the troops, thus enabling his comrades to fire into us with impunity. His appearance was so striking that he naturally attracted the attention as well as the fire of the command, although without effect, as the confounded rascal seemed to bear a charmed existence.73 At this juncture some of the packers displayed an utter disregard for personal safety, and running to the river bank at a point where the vegetation ceased, and a small stretch of sward intervened, turned handsprings and somersaults, yelling at the top of their voices, “head him off!” “hobble him!” “nosebag him!” and other kindred expressions peculiar to their profession, until the thing became really amusing.

For one hour the firing continued and some of us, especially those under fire for the first time, felt unusually blue. I must confess that the horrible whizzing of rifle balls was most demoralizing, and I for one, managed to keep well behind a large cottonwood tree, although for appearance sake, I blazed away with a vengeance until the atmosphere around that tree resembled a foretaste of the hereafter (the other place). Tom Cooper, a reckless sort of a fellow, and one of Closter's train, passing by, remarked: “I thought you'd find a tree rather convenient,” and away went all my grand ideas of bravery, and the humiliation of the situation burst upon me in all its vividness.

It seemed impossible to dislodge the enemy, by platoon or any other kind of firing, and it was at last determined by the General, that a charge would effect the purpose. Ordering companies M, A, I, and E, out upon this duty, the little party, under command of Capt. Mills, swam the river, and picketing their horses upon the other bank, stormed the hill with decided success.

In a few moments they had driven the enemy beyond the bluff and into the valley upon the other side, without loss, and it was now safe to leave our shelter, as the hiss of bullets had ceased. It is of no use talking; a fight with the possibilities of you don't know what, before you, is anything but pleasant, and upon the battlefield, the beauties of peace are greatly enhanced.

Thus ended our first brush with the enemy, and taking into consideration the fact that our loss was only in wounded, we got off very well. Of the enemy, it is always an almost impossibility to tell their loss, as they bear off their dead and wounded in a remarkably rapid manner. We lost several animals, and this with a few wounded, included our casualties, although during the fight, or skirmish rather, the firing was hot enough to have occasioned a heavy list of killed. I think it was due to the fact of abundant shelter at hand that our casualties were so slight, for upon an open field, I am confident we would have suffered severely, as the enemy were almost all of them armed with Winchester repeating rifles.

INTERLUDE

Sitting Bull “A unique power among the Indians”

Sitting Bull in his own words:

I never taught my people to trust Americans. I have told them the truth—that the Americans are great liars. I have never dealt with the Americans. Why should I? The land belonged to my people. I say I never dealt with them—I mean I never treated with them in a way to surrender my people's rights. I traded with them, but I always gave full value for what I got. I never asked the United States government to make me presents of blankets or cloth or anything of that kind. The most I did was to ask them to send me an honest trader that I could trade with, and I proposed to give him buffalo robes and elk skins and other hides in exchange for what we wanted. I told every trader who came to our camps that I did not want any favors from him—that I wanted to trade with him fairly and equally, giving him full value for what I got—but the traders wanted me to trade with them on no such terms. They wanted to give little and get much. They told me that if I did not accept what they would give me in trade they would get the government to fight me. I told them I did not want to fight.74

From Major James M. Walsh of the Northwest Mounted Police:

In point of fact he is a medicine man, but a far greater, more influential medicine man than any savage I have ever known. He has constituted himself a ruler. He is a unique power among the Indians.…Sitting Bull has no traitors in his camp; there are none to be jealous of him. He does not assert himself over strongly. He does not interfere with the rights or duties of others. His power consists in the universal confidence which is given to his judgment, which he seldom denotes until he is asked for an expression of it. It has been, so far, so accurate, it has guided his people so well, he has been caught in so few mistakes, and he has saved even the ablest and oldest chiefs from so many evil consequences of their own misjudgment, that today his word, among them all, is worth more than the united voices of the rest of the camp. He speaks. They listen and they obey.75

In the words of Abbot Martin Marty, a missionary:

Sitting Bull was proud that he knew nothing of the language and customs of the pale face, and avoided learning them. He obtained and maintained supremacy over his tribe simply by superior natural cunning. He was essentially a demagogue, following the will of the majority instead of shaping their opinions. He was originally a medicine man, and the warriors rallied around him because they discovered in him the qualities of personal courage and shrewdness. He was never chosen chief, nor do the Sioux ever elect a chief. They simply follow the man they believe to possess superior wisdom until they lose faith in him, when they rally around some other person who happens to have the ascendancy in their good opinions. One secret of Sitting Bull's long continued popularity is his extreme reserve and apparent humility. He is among the poorest of his tribe.…He was also very devout, according to the savage idea of devotion, and this quality won him respect. He observed with strict fidelity all the ceremonies of his pagan religion, such as the sun dance and the new moon dance. He worships the sun, the moon and earth, and believes that he hears the voice of God in the wind and the roar of waters. His personal habits are simple by choice as well as by necessity. He despises the costumes of civilization. A shirt, a pair of leggings, moccasins and a coarse blanket is all he wants. Buffalo meat is all the food he will eat. Whiskey he looks upon as the drink of evil spirits and will not taste it. He is as unostentatious in his manner as he is simple in his habits. He exacts no deferential treatment and lays no claim to being chief, though he is implicitly obeyed.76

And lastly, President Grant:

Correspondent—Mr. President, do you share the general admiration for Sitting Bull as a tactician—as an Indian Napoleon?

The President—Oh no! He is just as wily as most of the Indians who will never fight our troops unless they have them at a decided disadvantage.77