18

Last Rites and Last Rambles

“President Truman signed legislation today to pay $101,630 to Sioux Indians for ponies the Army took away from them after the Custer massacre…. The payments are to go to the Indians or their heirs.” —New York Times, July 4, 1945

“Every now and then something pops up in the day’s news to remind us how short the period of American history is and how closely it is all tied together.”—New York Times, July 24, 1946

Following the Sioux War of 1876 there was just one obstacle left to white settlement in the Yellowstone Valley: the large Crow Reservation that bordered the Yellowstone River. Although the Crow Indians have managed to hold on to a good-sized chunk of the eastern portion of their reservation, the outlook in the early 1880s was less than optimal that they would even have that section of land to show for their allegiance to the US government during its wars with the Sioux. In fact, over the next two decades, the Crow Reservation shrunk by intervals until by the early 1900s it was less than half its original size based on the 1868 treaty. Their cessions included all the land adjacent to the Yellowstone River. From the New York Times, April 4, 1880:1

While discussing the Indian problem in its relation to the Yellowstone Valley, I must not overlook the Crows. This tribe, which numbers about 900 or 1,000 warriors, is in many respects the most formidable tribe of Indians on our frontier. Their wealth in ponies is said to be almost incalculable, though 20,000 is probably a reasonable estimate of the size of the herd. The Crows, for some years, have been the warm allies of the whites, with whom they have gladly combined in hunting down their common enemy, the Sioux. By this association they have gained a knowledge of our tactics and methods of warfare which might operate to our disadvantage if they should ever go on the warpath against us. Besides this, they are excellently armed with the best patterns of breech-loading rifles manufactured in the United States, which they can use effectively, mounted as well as afoot. They are now on the friendliest terms with their paleface neighbors, and it is to be hoped that no question will ever arise to disturb the existing harmony. But clouds are beginning to appear on the horizon, the full import of which it is difficult to foresee. In the first place, the Crow Reservation is unquestionably the garden spot of the Yellowstone Valley, and as such it is exciting the envy of the white settlers. The reservation embraces all the territory west of the one hundred and seventh degree west longitude, south and east of the Yellowstone River and north of the Wyoming border, and includes 20,000 square miles of the most fertile and best-watered soil in Montana. There is an almost continuous chain of settlers along the north shore of the Yellowstone, from here to the Gallatin Valley, and the south shore would be quickly taken up also were it not for the Crow obstacle. The ranchmen on the north bank of the [Yellowstone] river opposite the reservation find themselves somewhat uncomfortably situated, from the fact that the northern buffalo herd, upon which the Crows depend for their food and their robes, and the hides to construct their tepees, or lodges, inhabits the upper portion of the Territory, and they are in constant danger of having their farms overrun by Indian hunting parties…. Meanwhile, the wave of civilization is washing the borders of the Crow country. Houses are constantly springing up on all sides. Valuable gold discoveries have been made on Clark’s Fork, in Wyoming Territory, but [are] only accessible by the Montana route through the reservation. The great cattle men of Western Montana have no ready outlet for their herds except by crossing the Crow lands, and this privilege is sternly denied them. Too many influences are operating concurrently for the removal of the Crows to make it probable that they will much longer occupy their present home, and it will be well, for various reasons, if the present Congress takes action on the petition for their removal which was recently sent to Delegate [Martin] Maginnis, at Washington, after receiving the signatures of nearly every white resident of the entire Yellowstone Valley. It is not difficult to foresee what will be the result if the Indians are not induced to sell out their claim amicably, and when, as will otherwise be the inevitable consequence, they find the whites determined to push them off their reservation. I, for one, shall wish to be as close to a military post as is possible. The flurry might be brief, but it would be destructive. I am not sounding an idle alarm but am giving expression to the declared sentiment of many of the oldest and coolest settlers of this region, with whom I have conversed upon the subject.

On January 29, 1879, the secretary of war proclaimed the Custer Battlefield a national cemetery. By the early 1890s (if not sooner), advertisements started to appear in newspapers and magazines touting the battlefield as an exciting travel destination for the curious and adventurous. This advertisement appeared in the Watertown (NY) Herald on December 9, 1893:

A visit to this spot, which is now a National Cemetery, is extremely interesting. Here, seventeen years ago, General Custer and five companies of the Seventh U. S. Cavalry, numbering over 200, officers and men, were cut to pieces by the Sioux Indians and allied tribes under Sitting Bull. The battlefield, the valley of the Little Big Horn, located some forty odd miles south of Custer, Montana, a station on the Northern Pacific Railroad, can be easily reached by stage. If you will write Chas. S. Fee, St. Paul, Minnesota, inclosing four cents in postage, he will send you a handsomely illustrated 100 page book, free of charge, in which you will find a graphic account of the sad catastrophe which overtook the brave Custer and his followers in the valley of the Little Big Horn, in June ‘76.

Jerome Stillson, who interviewed Sitting Bull in Canada in October 1877, died three years later, on December 26, 1880. He was about thirty-nine years old. His death was reported in the New York Times the following day:

Jerome B. Stillson, one of the best known journalists of this city, died at the St. Denis Hotel yesterday afternoon at 2:30. He had been suffering from Bright’s disease of the kidneys since last June, and was confined to his room for three or four weeks past. His body was taken to Merritt’s undertaking establishment, in Eighth Avenue, preparatory to its removal to Buffalo today. Mr. Stillson was born in Buffalo in 1841. During the latter part of the [Civil] war he became a special correspondent for the New York World, and rapidly rose to distinction as a journalist. When peace returned to the country he was made correspondent of the World in Washington, and in 1874 served as managing editor of that paper for a short term. He then became the Albany correspondent of the World, filling that position until 1875, when he went to Denver, Colorado, where he engaged in business in connection with Western lands. In 1877 he became attached to the staff of the [New York] Herald, his first notable productions in this capacity being a series of letters from Utah describing the evils of Mormonism. While engaged in this work he was shot at and wounded in Salt Lake City. Since then he has remained on the Herald staff, his last work having been done in Indiana during the [political] campaign of last September. Mr. Stillson leaves no family. He was married about 10 years ago to Miss Bessie Whiton of Piermont, N. Y., but she died a few years after the marriage.

Although Stillson’s obituary said he was to be buried in Buffalo, he was buried next to his wife in Piermont (Rockland County), New York.2 Outside of Mark Kellogg, the reporter who died in the battle of the Little Big Horn, Stillson was the first of the Sioux War correspondents to die.

Correspondent Joseph Wasson was appointed U. S. consul for the Port of San Blas, Mexico, in early 1883, but died shortly after, on April 18, 1883. He was about forty-two years old.3

Frontiersman Frank J. North, who led the Pawnee scouts at the Dull Knife battle, later became a Nebraska rancher and also joined “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” show. While performing in Connecticut on July 31, 1884, he was badly injured in a fall from his horse:

During the exhibition of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show at Charter Oak Park this afternoon a serious accident occurred to Major Frank North, the well-known interpreter of the Pawnee Indians and a ranchman of Nebraska. The cavalcade of about 100 Indians, cowboys, and attachés had started at a signal on a wild chase down the track, and had proceeded but a short distance when Major North was thrown by the breaking of his saddle girth. Though followed by many running animals, all going at a reckless speed, the skill of the drivers prevented a general trampling upon him. One horse, however, planted his forefeet in his side and back and five or six ribs were broken. Four thousand spectators witnessed the accident, but it was not generally known till the whole performance was over that any one was seriously harmed. Major North was taken to the Oakwood Hotel, and is as comfortable tonight as could be expected. He has been for years a great sufferer from asthma and there may be internal injuries which will make his recovery doubtful.4

North never fully recovered. He died on March 14, 1885, at age forty-five.

In 1882, George Crook was sent back to Arizona to fight the Apaches. His 1883 campaign into the formidable Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico was well-documented by Captain John Gregory Bourke (1846-1896) in his book An Apache Campaign in the Sierra Madre. When Geronimo escaped Crook’s grasp in 1886, the long-time Indian fighter was criticized for his overdependence on Apache scouts and asked to be removed from command, telling Sheridan (1831-1888): “It may be that I am too much wedded to my own views in this matter, and as I have spent nearly eight years of the hardest work of my life in this department, I respectfully request that I may be relieved from its command.”5

His new assignment found him back in the Department of the Platte. His replacement in Arizona was Nelson Miles (1839-1925), whose use of artillery in 1876-77 was too much for the already wearied Sioux and helped put an end to the Great Sioux War. Miles became a brigadier general in December 1880, and lived long enough to see World War I and air warfare. The thought must have crossed his mind that fighter planes would have come in handy against Sitting Bull and Geronimo.

Crook was promoted to major general in April 1888 and placed in command of the Division of the Missouri. It was his last assignment. He died about two years later, at age sixty-one. From the New York Times, March 22, 1890:

Chicago, March 21—Major Gen. George Crook, United States Army, in command of the Department of the Missouri, died at the Grand Pacific Hotel, at 7:15 o’clock this morning, of heart disease. He arose shortly before 7 o’clock apparently in his usual health, and, in accordance with his custom, began exercising with the weights and pulleys connected with an apparatus for the purpose which he kept in his room. After a few minutes he stopped and laid down upon a lounge, saying that he felt a difficulty in breathing. A few minutes later he called to his wife: “Oh, Mary, Mary; I need some help. I can’t get my breath.” Dr. Hurlbut, who lives near by, was sent for. Everything possible was done, but Crook failed to rally. Mrs. Crook and her sister, Mrs. Reid, were the only members of the family present at his bedside when he passed away. He had no children. Ever since he returned from his last trip to the Northwest he had been complaining of a bearing-down sensation in the neighborhood of the heart. In accordance with the wishes of Mrs. Crook it was arranged this afternoon that the funeral services shall be held on Sunday afternoon. The remains will then be put on board a special car, tendered by the Pullman Company, and will leave for Oakland, Md., at 3 o’clock, over the Baltimore and Ohio Road, escorted by the officers of the late General’s staff and a small detachment of soldiers as a body guard. Adjt. Gen. [Robert] Williams, on behalf of the widow, has asked a number of prominent citizens to act as pallbearers. In the meantime the body will lie in state in the parlor of the Grand Pacific Hotel, with a body guard of soldiers.

Upon learning of Crook’s death, Captain George M. Randall (1841-1918), of Crook’s staff, told a newspaper reporter:

We have noticed for some time that Gen. Crook was not in his usual health. He was a man who never complained and said very little about his sufferings. At the theater last night [March 20] I saw that he was not feeling at all well and asked him if he was in pain. He said, “No,” but I think that was the beginning of the end.6

In October 1877, General Terry met with Sitting Bull (then about forty-five years old) at Fort Walsh in Canada, but failed to convince the venerable and resolute chief to return to the United States. Sitting Bull told him:

The part of the country you gave me you ran me out of. I have now come here to stay with these people, and I intend to stay here. I wish you to go back and to take it easy going back.7

“By ‘taking it easy,’” correspondent Jerome Stillson explained, “Sitting Bull meant that the commission should take such a long time in going that it would never get back.”

The Hunkpapa chief held out on Canadian soil for a few more years, but when he could no longer support himself by the hunt (the Canadian government did not supply rations to his people) he was forced to return to the United States. In fact, many of his followers had already preceded him. He surrendered to Major David H. Brotherton, Seventh Infantry, on July 20, 1881, at Fort Buford in present North Dakota, at the head of 187 followers. In his own way, he never surrendered; when it came time to hand over his Winchester rifle, he did so through his five-year-old son, Crow Foot. Three years later, the famed Sioux chief toured with “Buffalo Bill” Cody for a few months. In 1889, he became angry with his fellow Sioux leaders after they signed an agreement to sell some eleven million acres of land on the Great Sioux Reservation to the US government for white settlement. When asked by a reporter what effect he thought this would have on the Sioux, Sitting Bull was quoted as saying: “Don’t talk to me about Indians; there are no Indians left except those in my band. They are all dead, and those still wearing the clothes of warriors are only squaws. I am sorry for my followers, who have been defeated and their land taken from them.”8 Sitting Bull was killed by Sioux Indian police while resisting arrest on December 15, 1890, on the Standing Rock Reservation, at the height of the Ghost Dance craze.9 He was about fifty-nine.

General Terry had retired from the army in April 1888 and moved to New Haven, Connecticut. With Sitting Bull now dead, he could finally breathe easy. Instead, he stopped breathing entirely on December 16, 1890. He was sixty-three. Perhaps he read about Sitting Bull’s death in the morning paper before passing. Well, it makes for a good story.

Captain William C. Rawolle of the Second Cavalry (he was promoted from lieutenant in December 1880) was in all of the major fights of the Wyoming Column in 1876, from the Reynolds fight on Powder River through Slim Buttes. He was also one of the officers who brought relief horses out to Lieutenant Sibley’s scouting party in early July 1876. His death was reported in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on June 12, 1895:

Captain William C. Rawolle, United States Army, died suddenly of heart failure at the home of his brother, F. Rawolle, 263 Hicks Street, early yesterday morning [June 10]. Captain Rawolle was visiting Brooklyn on sick leave. His regiment is stationed at Fort Logan, Colorado. In the exercise of his duty a few months ago Captain Rawolle contracted a severe cold, which developed into an attack of the grip. He partly recovered and obtained a leave of absence. He arrived in Brooklyn in April. Here he discovered that his sickness had affected his heart, which troubled him considerably. A few minutes after he had complained of a severe pain in the region of his heart yesterday he breathed his last. He was a native of Prussia and came to America, settling in New York City, with his parents, in boyhood. He was in his 55th year at his death. In 1861 the deceased enlisted in the army as a volunteer. He took part in seventeen fierce battles, including Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Antietam, during the war and came out unscathed. Most of the time he was on General Sturgis’ staff. At the close of hostilities he was made a colonel. Then he entered the regular army and had been a captain for twenty-five years. Captain Rawolle was expecting a major’s commission when he applied for a leave of absence. The deceased had seen much active service in Indian engagements since the close of the civil war, and was one of the reserve force sent to the assistance of General Custer in the latter’s fatal encounter with the confederated Sioux on the Little Big Horn in 1876. Captain Rawolle and his fellow rescuers arrived a few hours too late to save the life of Custer and his companions.10 The deceased subsequently helped capture Custer’s slayers. Captain Rawolle’s wife was with him at his death. His three children, who have not yet learned of their father’s death, are at the military post at Fort Logan. The funeral services will be held this evening. The interment will be in Greenwood Cemetery [in Brooklyn].

Thaddeus H. Stanton, the long-time paymaster (since the Civil War) who participated in the Reynolds battle in March 1876 and was a correspondent for the New York Tribune, went on to become paymaster general of the United States in 1895. He retired in January 1899, and died in Omaha on January 23, 1900, just seven days short of his sixty-fifth birthday. From the New York Times, January 24, 1900:

Stanton had been ill for a long time. He was known as the “fighting Paymaster” because of his insistence on a place in the line during the Indian outbreaks. Gen. Stanton was born in Indiana [in 1835], but when a child his parents went to Iowa to live, and from that State he went, with hundreds of others, to join John Brown in Kansas in 1857…. In 1875 he went with Gen. Crook on the Black Hills expedition, and a year later was chief of scouts for Gen. Crook, seeing hard service against the Indians then and in succeeding years. December 1890 found him in Omaha as Chief Paymaster of the Department of the Platte…. He often paid the troops in the field and courted danger rather than avoided it. He was appointed Paymaster General with the rank of Brigadier General in March 1895, succeeding General William Smith. Gen. Crook once said of Stanton: “His entire army life has been a period of unselfish, untiring, intelligent, and oftentimes heroic performance of duty.”

Cuthbert Mills, the New York Times correspondent who spent the latter part of the summer of 1876 with General Crook’s Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition, died on February 15, 1904. His death was reported in the New York Times two days later:

Cuthbert Mills, a member of the banking firm of W. S. Lawson & Co. of 40 Exchange Place, and for years a well-known writer on financial topics, died Monday night in his apartment, in the Ansonia. He had been ill a short time with pneumonia. Until he entered the banking firm, for which he wrote a weekly financial letter, he was identified with the daily newspapers of this city, and for a while was on the staff of The New York Times. He was a member of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Municipal Art Society. Much of his time was spent in his Staten Island home, and he recently established a church in that neighborhood. He was about fifty-six years old.

John F. Finerty, the only correspondent who accompanied the Sibley Scout, went on to several interesting adventures, including a three-month trip through Mexico in 1879, and reporting on campaigns against the Utes (1879) and the Apaches (1881).11 His death was reported in the New York Tribune on June 11, 1908:

Chicago, June 10—Colonel John F. Finerty, a well-known newspaperman, lecturer and Irish patriot, died at his home here early today, aged sixty-two years, from an ailment of the liver with which he had been suffering for six months.

Mr. Finerty left a wife and two children, John Finerty, Jr., assistant attorney for the New York Central Lines, and Miss Vera Finerty, a senior student in the University of Chicago.

John Frederick Finerty was a native of Galway, Ireland, where he was born on September 10, 1846. He was educated in the national schools of Ireland and with private tutors and came to this country in 1864. He served in the Union Army in the last year of the war. He also saw service in some Indian campaigns [as a correspondent]. In 1868 he became a reporter on “The Chicago Republican” and in 1871-72 he was city editor of that newspaper. He then joined the city staff of “The Chicago Tribune,” where he remained three years. From 1876 to 1882 he was a war correspondent of “The Chicago Times,” being engaged in reporting the Indian wars on the frontier. Returning to Chicago in 1882, he founded “The Chicago Citizen,” and the same year he was elected to Congress as an Independent and served one term. He advocated the increase of the navy and additional fortifications. In 1884 he was an ardent supporter of Mr. Blaine for President and acted thereafter with the Republican party until 1900, when he supported Mr. Bryan on the anti-imperialistic issue. He was a radical advocate of Irish independence and served seven times as president of the United Irish Societies of Chicago. For three terms he was president of the United Irish League of America. Mr. Finerty was a popular lecturer on historical subjects, American, Irish and cosmopolitan. He was the author of “Warpath and Bivouac” and “The People’s History of Ireland,” and edited “Ireland in Pictures.” He was a member of the Grand Army of the Republic and the American-Irish Historical Society.

John V. Furey, Crook’s quartermaster for the 1876 campaign, was made a brigadier general on February 24, 1903, and retired the following day. He returned to his birthplace, Brooklyn, New York, where he died on December 17, 1914, at age seventy-five. From the New York Times, December 18, 1914:

Furey is survived by his widow, who was Miss Georgianna C. Grosholz of Philadelphia. His brother was the late Robert Furey, an old-time Democratic politician in Brooklyn. When he died, in the early part of 1913, he willed his estate, said to be worth between one and two million dollars and assessed at $500,000, to John Morrissey Gray of Brooklyn, who had been his associate for eighteen years. The will cut off all relatives and Gen. Furey brought suit to have it set aside. The suit was compromised on Oct. 8, 1913, by Gray paying Gen. Furey $65,000.

James J. O’Kelly, the correspondent of the New York Herald who arrived at General Terry’s camp at the mouth of the Rosebud on the first day of August 1876, moved back to the British Isles a few years later and eventually became a member of the House of Commons. He died December 22, 1916, and his death was reported in the New York Times on the following day:

Mr. O’Kelly was widely known for his adventurous career. He was one of Parnell’s earliest recruits in Parliament, and went through the ritual of suspension and removal from the House which marked the early eighties. While still a member of Parliament he accepted a commission to go up the Nile during the Sudan campaign and interview the Mahdi, but Lord Kitchener barred that enterprise. Mr. O’Kelly fought in the Franco-Prussian war, having a commission in the French Army. His passion for adventure also found an outlet in the United States Army during the Indian campaigns of a generation ago. At the time of the Cuban revolt against Spanish rule he served as a correspondent for New York and London newspapers and distinguished himself by his daring. Mr. O’Kelly was born in Roscommon, Ireland, and was in his seventy-first year.

Italian-born John Martin (his birth name was Giovanni Crisostomo Martini) will forever be remembered as the last white man to see Custer alive and the soldier who delivered the famed general’s last message. He retired from the army in 1904, after thirty years of service. On December 18, 1922, Martin was hit by a truck while crossing the street, his injuries being further complicated by a lung condition.12 He died six days later, on the twenty-fourth, at age sixty-nine. His death was reported in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on December 26, 1922:

John Martin, believed to be the last survivor of the Custer massacre on the Little Big Horn, died Sunday in the Cumberland Street Hospital, at the age of 69…. He is survived by his widow, his daughter, Mrs. Julia Jenson of 4218 5th Ave., three other daughters, Mollie, Jane and May, and four sons, George, John, Frank and Lawrence Martin. The funeral will take place tomorrow afternoon at 3 o’clock, from the home of Mrs. Jenson. Interment will be in Cypress Hills [Brooklyn], where the military honors will be accorded him.

Curly, the Crow guide who escaped death at the Little Big Horn by leaving Custer’s command before it was too late to do so, lived forty-seven more years. He died on May 22, 1923, “of a fever which failed to yield to his primitive methods of treatment.” He was about sixty-seven years old. His widow and son inherited his estate of over $11,000, “besides a yearly annuity from the Government in recognition of his services.”13

In 1888, Reuben Briggs Davenport made some headlines with his new book, The Death-Blow to Spiritualism: Being the True Story of the Fox Sisters. He also remained in the newspaper business for the rest of his life, eventually ending up in France as the chief editorial writer of the New York Herald’s Paris edition, a position he held from 1920 until he died in February 1932, at about age eighty.14 Were Davenport’s criticisms of General Crook during the 1876 Sioux Campaign accurate, or was he just trying to be controversial and somewhat antagonistic in order to sell newspapers and make a name for himself as a reporter in his early twenties? As of this writing, there seems to be no way to definitively answer that question. However, motives aside, the fact is that our knowledge of the Sioux War is all the richer through his descriptive and informative dispatches. No book on the Sioux War of 1876 can be complete without utilizing Davenport’s many newspaper reports. The man also had a romantic side, as witnessed by the following poem:

A Mirage

I see her from the crowd,

Nor seek her fated glance;

How strange that we should meet

By this ignoble chance!

At times her eyes greet mine

With fire too quick reproved,

As if ’twere ages hence,

The hour when we first loved.

A little hour, alack!

So swiftly sped it then;

In vain to turn the glass

And count the sands again.

I stand beside the sea

And watch its wavering gleam,

And ask my dull despair

Whence rose so fair a dream.

A vision ’twas unreal,

A mirage of the shore;

The echo in my breast

Is but the ocean’s roar!15

Ohio-born Edward S. Godfrey, a lieutenant in Company K, Seventh Cavalry, in 1876, retired with the rank of brigadier general in 1907. He lived twenty-five more years, dying at age eighty-eight at his wife’s ancestral home in Cookstown, New Jersey. From the New York Times, April 2, 1932:

Cookstown, N. J., April 1—Brig. Gen. Edward S. Godfrey, veteran of the Indian wars, died here tonight at the age of 88.

Indian fighter, Medal of Honor man and a veteran of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, in which General Custer and his troops were wiped out by the Indians, General Godfrey spent more than a third of a century in the service of his country. Besides taking an active part in the contests which wrested the West from the red men, he saw active service in the Civil War and in the Philippine and Cuban campaigns.

Born in Kalida, Putnam County, Ohio, Oct. 9, 1843, General Godfrey’s military career began when he was 17 years of age. His father could not dissuade him from answering Lincoln’s first call for volunteers, but he exacted a promise that his son return to school after his first enlistment of three months. The promise was kept, but in 1863 he won an appointment to West Point.

At his graduation as president of his class, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Seventh Cavalry, of which Lieut. Col. George A. Custer, Brevet General of the Civil War, was the commander. He became a captain [in December 1876] soon after the massacre at the Little Big Horn and had advanced to the grade of colonel by the time of the Spanish-American War. He then received a command of the Ninth Cavalry [June 26, 1901], a Negro regiment, which he led in the Philippines and in Cuba.

An officer of the Seventh Cavalry in the days when the West was won, Godfrey rode the plains for twelve years fighting Indians almost continually. General Godfrey received the Medal of Honor for conspicuous gallantry when, as a captain, he led his troop in action in the Bear Paw Mountains, Idaho [Montana], against the famous Chief Joseph of the Nez Perces on September 30, 1877.

General Godfrey was instructor of cavalry tactics at West Point from 1879 to 1883 and a pioneer in modern army equitation [horseback riding]. He was for a time commander of Fort Riley, Kansas, and of the school of application for cavalry and field artillery. Retired as a Brigadier General in 1907 he made his home at Cookstown in the pines of South Jersey in a colonial house which had been in the possession of Mrs. Godfrey’s family for more than 200 years.

General Godfrey emerged from his retirement to take part in the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the battle of the Little Big Horn, in 1926, and the peace ceremonies on Custer Ridge, near Garry Owen, Montana. A former commander of the Kansas commandery of the Loyal Legion, he was also a past commander of the Department of Arizona, G. A. R. [Grand Army of the Republic];a former commander and historian of the Military Order of Indian Wars, a former senior vice commander of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion, and commander of the Army and Navy Legion of Valor.

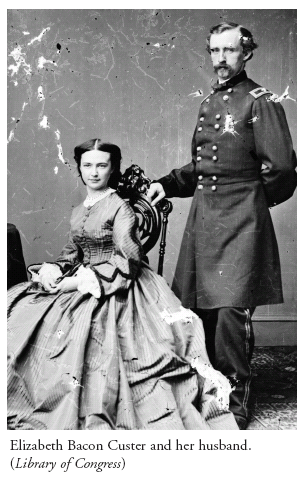

Shortly before the close of 1876, Elizabeth Bacon Custer received $4,750 from the New York Life Insurance Company, little compensation for the ill-timed loss of her husband. It would have been an even $5,000, but she had to pay a $250 “war premium.”16 She outlived her legendary husband by almost fifty-seven years. The three books she wrote about her life with George Custer have been reprinted ever since: “Boots and Saddles” (1885), “Tenting on the Plains” (1887), and “Following the Guidon” (1890). As a matter of fact, she fairly dedicated the rest of her life to the cherished memory of her husband, as exemplified by this 1896 article:

Gen. Custer’s most faithful biographer has been his wife. It was nearly ten years after his death before Mrs. Custer could summon courage to give the story of her hero to the world. Writing of her initial effort in compiling “Boots and Saddles,” Mrs. Custer says in a letter not hitherto published:

“I never should have had the courage at all to do the work if I had not longed to tell something of my husband’s home life. It has always seemed to me that few men who compel the admiration of their country, lived so beautiful a social life as my husband. He was so unselfish, boyish and unaffected in his own home that it used to seem incredible that he was the same man about whom admirers of his public career flocked whenever we left our home. His relations with his intimate friends, his family, his soldiers and his servants were worthy of a better pen than that of his wife in describing them, and so I told my story in describing him, without having it presume to be anything as difficult as a life. If I had not so grand a subject I would not now feel such humiliation that I could not do better.

“If I can only learn to write more of my hero and keep him before his country I shall not have lived after him in vain.”17

Mrs. Custer died on April 4, 1933, four days short of her ninety-first birthday.

Massachusetts-born William E. Morris was a private in Company M at the Little Big Horn, where he was wounded in the left breast. He left the army in 1878, at age twenty, and went to New York, where he worked his way up the social ladder from waiter, to lawyer, to judge. He died on November 26, 1933, at age seventy-five. From the New York Times, November 27, 1933:

Municipal Court Justice William E. Morris of the Second District in the Bronx, who fought with Custer in the battle of the Little Big Horn, died yesterday of arterial sclerosis at his home, 2780 Pond Place, the Bronx, at the age of 75. Illness had prevented his holding court since last June. His son, William E. Morris, Jr., a civil engineer in the Bronx Sewer Department, survives.

When in 1878 he bade farewell to Indian fighting and the United States cavalry, Justice Morris came to New York. For a few years he made his living as a Bowery waiter and used his spare time in studying law. Soon after gaining admission to the bar he formed the firm of Morris, Kane & Costello, which developed a lucrative criminal practice. He also joined Tammany Hall and entered politics, serving one term in the State Assembly, and two terms as Alderman. For some years he held the Democratic leadership of the old Thirty-fifth Assembly District. He resigned this post when he was elected in 1911 for the first of three successive ten-year terms, as a justice of the Municipal Court. The final term will end on December 31, 1941.

When the battle of the Little Big Horn was fought in June 1876, William E.Morris was 17 years old. He had advanced his age four years to obtain an enlistment in Boston, his birthplace.18 At the same time of the battle his regiment, the Seventh United States Cavalry, was divided into three columns. Trooper Morris, in the one led by Major Reno, fought most of the engagement in the valley. Custer was on the other side of the hill. As he moved off with the Custer column, Byron L. Tarbox, half-brother of the justice, called out to him: “Look out for your scalp, Bill. The Indians don’t like red-headed fellows.” The justice had red hair in those days. But he lived to tell the tale and he never saw Byron alive again.

The Reno column reached the top of the hill after many losses. Justice Morris was wounded, but managed to entrench himself and spent the night firing at flashes below him. After two months in a hospital he served throughout the Nez Perce campaign. His son last night was reluctant to say that his father was the last survivor of the battle, but he knew of no other. He was a former captain in the Sixty-ninth Regiment, N. Y. N. G. [New York National Guard], a member of the Society of Indian Wars, Royal Arcanum and the Elks.

Lovell H. Jerome was a lieutenant in the Second Cavalry in the fight against Lame Deer on May 7, 1877. He secured his place in history that October when he was taken prisoner by the Nez Perce and exchanged for Chief Joseph after that leader had been taken hostage by Colonel Miles during the Battle of the Bear Paw in northern Montana. Jerome resigned in April 1879 due to excessive drinking, then signed up again for a couple of years in the Eighth Cavalry in the early 1880s. Once again, his love of alcohol brought an end to his army career. In his old age, Jerome looked back fondly on the good old days of cavalry versus Indians. From the New York Times, August 6, 1933:

These are dull days for an Indian fighter, “Colonel” Lovell Hall Jerome acknowledged yesterday. In 1877 the “Colonel” was fighting the Sioux; nowadays, he is fighting off boredom. And he is still a good warrior—means to keep right on fighting.

Today will be the “Colonel’s” eighty-fourth birthday anniversary, but he does not intend to let that interfere with his customary program. He will spend most of the day in his familiar armchair, at 829 Park Avenue, just as he spent most of yesterday. At the proper time he will go out for his daily stroll and luncheon at a neighborhood restaurant, where he will order as many steins of beer as he happens to feel like drinking. No more, no less.

Sometimes, when he gets to thinking about it, the “Colonel” misses the frontier life, which was always spiced “with enough danger to make it interesting.” In 1877 he was exchanged as a hostage by the Nez Perces tribe, and it was his troop, under Colonel John Gibbon’s command, which arrived at the junction of the Big Horn and Little Big Horn rivers two days after the massacre of General Custer and his 264 men in 1876.

“Colonel” Jerome, whose title is honorary, since he was only a Lieutenant when he retired in 1879, is now old enough to get a special birthday card from the West Point Military Academy every year. And he looks forward to the day when he will be the oldest living graduate. But the trouble is how to amuse himself in the meantime.

He used to play a pretty good hand at auction bridge, but as soon as contract became the rage he gave it up, a little scornfully. “People have to devote their lives to that game,” he said. Nowadays, he sticks to detective stories and euchre. He doesn’t like motion pictures, can’t sit still long enough to see one through, he explained. “Of course, they’re wonderful things,” he added, “for people who can stand ’em.” He can’t.

A New Yorker for eighty years, he misses the old-time “neighborly spirit.” He remembers making the New Year calls for his family in 1872 when he was home on leave. In a sleigh, drawn by three horses, he called on more than a hundred families and only ten lived above Forty-second Street. He does not remember whether he took a drink at every house he visited, but thinks it very likely, as that was the custom.

“Colonel” Jerome goes motoring occasionally, but says he will never set foot in an airplane. He wouldn’t mind it if he could trust the pilot to bring him back promptly, as soon as he’d had a chance to look around. But once in the air, he thinks a frivolous pilot might say to himself: “Now that I’ve got the old man up, I might as well pull a few stunts.” The “Colonel” was never much afraid of Indians, but he’s afraid of that, and he admits it.

Jerome died on January 17, 1935, at age eighty-six, with the distinction of being West Point’s oldest living graduate at the time.

Charles A. Varnum was born in Troy, New York, in June 1849, and was a lieutenant in Company A, Seventh Cavalry, at the time of the battle of the Little Big Horn. Still with the Seventh Cavalry fourteen years later, he earned the Medal of Honor for his part in a fight with the Sioux on December 30, 1890, the day after the Wounded Knee Massacre. He died at age eighty-seven on February 26, 1936. He was the last surviving officer that rode with Custer to the Little Big Horn. From the New York Times, February 27, 1936:

On graduating from West Point in 1872 Colonel Varnum was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Seventh Cavalry. In the Battle of the Little Big Horn in June 1876, he was wounded while fighting with Reno’s battalion, which, unlike the two [battalions] under Custer,19 escaped annihilation. In all, he served thirty-two years in the Seventh Cavalry.

In June 1876, John M. Carnahan had been the telegraph operator in Bismarck. It took him twenty-two hours to transmit all the reports related to “the story of the Custer massacre on the Little Big Horn.” He died in Missoula, Montana, on October 24, 1938, at the ripe old age of eighty-nine.20 From the New York Herald Tribune, June 30, 1957:

Fifty thousand words later—and a “Herald” telegraph toll of more than $3,000—the East had been informed and shocked and filled with fury against the Sioux. Custer became a hero anew. The Sioux were forever damned. The story broke in “The Herald” on July 6, the same day a garbled report had been published in Wyoming and Montana. Many Eastern papers refused to print the Custer story because it appeared unrealistic. Then Gen. Sheridan issued a denial. “It comes without any marks of credence; it does not come from Headquarters—such stories are to be carefully considered,” he said boldly.21

Following the Sioux War, correspondent Robert E. Strahorn wrote several propaganda-style books about the West and Pacific Northwest (unfortunately he did not include his experiences with General Crook during the Sioux War)22 and was employed in the publicity department of the Union Pacific Railroad from 1877 to 1883. He was also one of the founders of the College of Idaho in the early 1890s. He lived through World War I and most of World War II, and outlived all of the other Sioux War correspondents. He died on March 31, 1944, at age ninety-one.23

The last surviving soldier of the Seventh Cavalry who participated in the Battle of the Little Big Horn was German-born shoemaker Charles Windolph of Company H. He was in Benteen’s battalion and took part in the defense of Reno Hill where he was wounded in the posterior. More importantly, on June 26 he helped provide covering fire for other troopers who had to make themselves targets for the Indians in order to obtain water for the wounded. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in October 1878 for his valor during the Little Big Horn battle. He also received the Purple Heart on his ninety-fifth birthday for the wound he had received seventy years earlier.

Windolph died on March 11, 1950, at age ninety-eight. From the New York Times, March 12, 1950:

Born in Germany [on December 9, 1851], Mr. Windolph came to the United States when he was 19 years old, and two months later enlisted in the Army. He served for twelve years, leaving because his wife felt it was “not the place for a married man.” Most of his Army career was spent in Dakota Territory. He was on the 1874 Custer expedition to the Black Hills, during which gold was discovered, leading to the gold rush of 1876. After leaving the Army [in March 1883], Mr. Windolph came to Lead [South Dakota]—then a frontier gold-rush camp—and worked for the Homestake Gold Mine until he was pensioned eighteen years ago.

Jacob Horner hailed from New York City and enlisted in the Seventh Cavalry at age twenty on April 8, 1876, about six weeks before the Terry-Custer column departed Fort Abraham Lincoln. He was assigned to Company K, but he was not assigned a horse (there were not enough to go around, least of all for new recruits) and found himself walking, along with seventy-seven other cavalrymen, when the Dakota Column marched west on May 17, 1876.24 It turned out to be a lucky circumstance. Not having a horse, he was left behind at the Powder River Depot when Custer headed up the Yellowstone on June 15. Horner lived seventy-five more years after the famous battle, and when he died on September 21, 1951, about two weeks before his ninety-sixth birthday, he was the last living soldier of the Seventh Cavalry affiliated with the historic campaign of 1876. From the New York Times, September 23, 1951:

Bismarck, N. D., Sept. 22—Sgt. Jake Horner, who escaped the massacre at Custer’s “Last Stand” because there was a shortage of horses, died here last night of pneumonia. He was 96 years old.

Mr. Horner was the last survivor of Gen. George Custer’s Seventh Cavalry Regiment, cut down by the Indians in the battle of the Little Big Horn. He and a number of troopers who lacked mounts were left behind while Custer and his regiment rode off to their fatal engagement.

He was a veteran of a bitter battle against Chief Joseph and a valiant band of Nez Perce Indians [in 1877] and participated in Custer’s 300-mile forced march to the Powder River.

Mr. Horner left the Army in 1880 “because I met a girl and married her.” He retired from a prosperous meat business when he was 74, but acted as an adviser to film companies on frontier movie scripts.

And whatever became of Major Marcus Reno and Captain Frederick Benteen? Reno was court-martialed for “conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman” in 1877 and 1879, and was finally dismissed from the army on April 1, 1880, after nearly twenty-three years of service. He died of cancer on March 30, 1889, at age fifty-four. From the Dodge City Times, April 4, 1889:

Washington, D.C., April 2—Major Marcus Reno, late United States Army, who served with General Custer in the Yellowstone Sioux massacre, died at Providence hospital. Major Reno about three months ago became afflicted with a cancer on the tongue. The cancerous portion was removed last week by Dr. John B. Hamilton. A few days ago erysipelas set in the right hand and there was pneumonia of both lungs, which brought about his death in a few hours.

Benteen went on to fight against the Nez Perce Indians in 1877, was appointed major of the Ninth Cavalry in December 1882. He was brevetted a brigadier general in February 1890 for his services at the Little Big Horn in June 1876 and against the Nez Perce at Canyon Creek, Montana, in September 1877. He was suspended from the army for one year in April 1887 for drunk and disorderly conduct and received a medical discharge in July 1888, after more then twenty-six years of service (he suffered from impaired vision, frequent urination, and neuralgia).25 He died ten years later, on June 22, 1898, at age sixty-three. From the New York Sun, June 23, 1898:

Gen. F. W Benteen, formerly one of the best-known officers of the regular army, died in Atlanta yesterday. His death resulted from a stroke of paralysis. Although a native of Virginia he joined the Union forces, and conducted himself so gallantly throughout the civil war that at its close he held the title “Colonel of 138th United States Infantry.” He also made himself famous during the Indian wars. He also was one of the few survivors of Custer’s fight. He had lived in Atlanta since 1888.

Both Reno and Benteen will forever be tied to Custer’s controversial legacy, and while Custer’s death may have been a foregone conclusion at the battle of the Little Big Horn even if they had tried to follow his trail without delay, the fact that they dug in on a bluff while gunfire was heard downstream has left their conduct under a cloud of suspicion from which they will likely never escape.

At the time of this writing, Charles St. George Stanley and Jerry Roche have disappeared into history.

INTERLUDE

“Wiggle-Tail-Jim and ,Scalp-Lock Skowhegan”

Some may recall fondly the classic TV series F Troop from the 1960s that poked fun at the Old West, particularly the cavalry-versus-Indians theme. In the episode “Old Ironpants,” there was a scene in which Captain Wilton Parmenter (played by actor Ken Berry) said to George Custer (played by actor John Stephenson), “Good luck on your new assignment at Little Big Horn.” If you just smiled (and I’d bet you did), then you will enjoy this next section. First up is a brief story about a practical joke Custer played on a friend who was visiting him from New York. It was printed in the Colorado Transcript, September 6, 1899. It is followed by a handful of witty remarks and one-liners concerning the Great Sioux War and its participants.

Colorado Transcript (Golden City), Wednesday, September 6, 1899

CUSTER’S JOKE ON OSBORN.

The late Charles Osborn, the New York broker, and General Custer were intimate friends, and Osborn annually visited the general at his camp on the plains. During one of the Indian campaigns he invited Osborn and a party of friends out to Kansas, and after giving them a buffalo hunt, arranged a novel experience in the way of an Indian scare. As Osborn was lying in his tent one night, firing was heard at the outposts and the rapid riding of pickets. “Boots and saddles” was the order in the disturbed atmosphere of the night, and Custer appeared to Osborn loaded with rifle, two revolvers, a saber and a scalping knife.

“Charley,” he said, in his quick, nervous way, “you must defend yourself. Sitting Bull and Flea-in-Your-Boots, with Wiggle-Tail-Jim and Scalp-Lock Skowhegan, are on us in force. I didn’t want to alarm you before, but the safety of my command is my first duty. Things look serious. If we don’t meet again, God bless you.”

The broker fell on his knees. “My God, Custer,” he cried, “only get me out of this! I’ll carry 1,000,000 shares of Western Union for you into the firm to get me home. Only save me.”

But Custer was gone, and the camp by shrewd arrangement burst into a blaze, and shots, oaths and war-whoops were intermixed, until suddenly a painted object loomed on Osborn’s sight, and something was flung into his face—a human scalp. He dropped to the ground, said the Lord’s prayer, backward, forward and sideways, until the noise died away, and there was exposed a lighted supper table, with this explanation on a transparency: “Osborn’s treat!”

“The Indians stripped Custer’s men and [now] the Black Hillers and other citizens in the Sioux country will be able to buy army clothing from the post traders at very reasonable rates for some time to come.”

—Daily Colorado Chieftain, July 14, 1876

“The ‘friendly Sioux’ are getting up a numerously signed protest against the practice of cutting the hair short so prevalent in the army. Inspector Vandever will present it to the Indian bureau and endeavor to get Secretary Cameron to issue an order against the practice as it detracts from the ornamental appearance and greatly injures the value of the scalp.”

—Daily Colorado Chieftain, July 14, 1876

“A peace policy which swallows up a regiment of cavalry at a gulp is really not much of a success as a peace policy.”

—Daily Colorado Chieftain,July 20, 1876

“The slaughter of Custer’s command strengthens our belief that the only good Indians in this country are those standing in front of cigar stores.”

—Daily Colorado Chieftain, July 21, 1876

“The Custer massacre has caused a marked increase in the sale of [James Fenimore] Cooper’s novels.”

—Deseret News, August 2, 1876

“The Indian is not a bad looking man. It’s the war paint that makes him look ghastly and hideous. Nothing else in the world could give him the same awful appearance, unless it is a pair of linen pants.”

—Daily Colorado Chieftain, August 6, 1876

“Sitting Bull has been badly defeated several times—in the newspapers.”

—Deseret News, August 30, 1876

“Several men who were reported killed with General Custer have come to life again. They were not with his command.”

—Harper’s Weekly, September 2, 1876

This next news clipping was unintentionally humorous in its absurdity:

“One of the chiefs who led the Sioux against Custer on the Little Big Horn has unmixed white blood in his veins. He was born in Pike County, Missouri, his father being one of the pioneers of Missouri and a veteran of the Mexican war. He was captured by the Indians when a boy, grew up among them, and finally became their chief.”

— Harper’s Weekly, September 2, 1876

“The campaign against the Indians will shortly come to a close…and the official reports thereof may soon be expected to be sent in. Briefly they may be somewhat as follows—

Custer’s—‘We met the enemy and we were theirs.’

Reno’s—‘We met the enemy, but were sorry we did. We were almost theirs, but, thanks to help at hand, we escaped with the skin of our teeth.’

Crook’s—‘We met the enemy, but were glad to retire in good order.’

Terry and Crook’s—‘We have not met the enemy, so we are not theirs and they are not ours. We have not discovered the enemy, and we cannot find out whether there is any or not. We have seen a big trail, but have never caught a glimpse of the big trail-makers.’”

—Deseret News, September 13, 1876

“Buckskin Sam,” the oldest guide in the State of Maine, and who was with General Custer at the massacre of the Little Big Horn in the Black Hills, was voted the prince of story tellers at the annual congress of the Tale Teller’s Club last night at the Putnam House.

—New York Times, March 4, 1907