Travel Day 10: Winds

Our last day. In retrospect, a visit to the ocean again was fitting. Imagine the soldiers looking out to sea as they boarded a ship again, but this time it was home they were headed. For Private Albrecht, that was at Le Havre in France, not far from Omaha Beach where he first set foot fifteen months earlier. And here we were, the three of us road-trip tourists, now having circled back to the Netherlands for our flight home in the morning. The ocean seemed to beckon us for one last look at the beach and pounding waves, promising a bit of serenity from our regimented cross-country travel.

We set off from Den Bosch, “the forest” as it is translated. Liberated by the British in October 1944, Den Bosch had been the site of a Nazi concentration camp, one of the few German complexes in western Europe located outside of Germany and Austria. We might have opted for staying put this last day, off the highways with little risk of getting lost again, just leisurely taking in the various historic sites, many of which remained intact through the war. But the sea was calling us.

On our way to the coast, we scheduled a special stop at the village of Kinderdijk, an area where we would see the famous authentic windmills, the Dutch icon known throughout the world. Then too, there would be the tulips we still hoped to see. Even the cold wind and heavy rain didn’t seem to dampen our spirits for this one last day of touring.

1992 – Windmills at Kinderkijk. (Author’s Collection)

The Kinderdijk vicinity is most unusual: By all accounts it should be flooded, situated as it is up to seven meters below sea level. But the Dutch have an innovative and intricate system to prevent flooding that involves canals and a unique collection of seventeen windmills dating back to the 1700s. This unusual lay of land and water can be unnerving—one can stand looking in the distance and see above the grass landscape only the top of a passing boat which is tucked in a canal. Amazed and enlightened, we inched along the roads to view all of the lovely windmills. In this setting of golden grasses, green patches with grazing sheep, and an occasional resident hunkered down on a bicycle in the brisk wind, even the heavy gray skies lent a beautiful take on our photos.

“Sure is pretty, isn’t it? Even the wind . . . it’s nice.” Dad was in his element. He pulled his cap down and turned up his collar as we stood outside the car for a better look. Now away from the busy highways, the city noise and traffic, the natural world seemed suddenly to appear like a dose of therapy especially formulated for us weary car travelers. Even finally accepting the fact that tulips were not yet in bloom, not even close, we were fully content with the beauty of the Dutch countryside mid-March.

“Nothing like the great outdoors, right, Russ?” Wilt could see that driving on further to see the ocean was going to be a good choice for this last day. “Let’s go take a look at the North Sea. Remember, that’s where George was stationed.”

Good thing we had the rejuvenating windmills because getting to the coast meant getting through The Hague. Our experience of being lost yet again gave new meaning to the city’s name: The Hague translates roughly to “the hedge” or “the wood.” Countless wrong turns thrown in with unfortunate detours sent our blood pressure back up to borderline high. That is, Wilt and I were feeling it. We had agreed that this, our last day of our once-in-a-lifetime trip for Dad, needed to be special. For once, just once, we needed to know our way around. Instead, this thicket of a city had us foiled again. As we took turns darting to VVVs for tourist information, Dad waited patiently in the car whistling that nondescript tune he whistles when he waits.

It’s no wonder we lost our way in this city of a million people. Though Amsterdam is the capital of Holland, The Hague is the administrative capital, the seat of government, even including several international courts. The city was the site of the world’s first peace conference held in 1899 and is known today as “the City of Peace and Justice.” Situated just inland from the North Sea, the city also is called “the Residence” because many of the members of the Dutch Royal Family reside in the chic neighborhoods. And despite the formal tones of government at work, the city also boasts lively night clubs, eateries, and shopping, along with its museums and cultural attractions.

Of course, the chic neighborhoods and lively entertainment were not what we were after, but the sea. Just get us to the sea! At long last, after more than a reasonable number of stops, and around that last bend, there it was—not the upscale seaside resort Scheveningen, touted in The Hague as the best on the Dutch coast, but a simple, plain, seemingly unending, beach. The gushing waves, the raw wind, the big cloudy sky—we took it all in. And like Omaha Beach, we were the only ones there. Our thin jackets were no match for the weather this day so we soon took shelter back in the car, but we sat a long while in silence viewing out the windows, absorbing the powerful seascape.

1992 – The North Sea. (Author’s Collection)

“I told you about that rough ride home through that end-of-November North Sea storm, didn’t I?” Dad’s eyes were fixed on the horizon.

“You sure did, Russ. These waves we’re looking at here, are probably calm compared to that, right?” Wilt and I smiled.

“Darn, right,” Dad smiled back. “And don’t forget, out there someplace is where George was on a German boat for old Adolf. That’s about the time I was fighting in the Ardennes, I suppose . . .” He paused. “That dammed war was a big one.”

We stayed a while longer until the sun was sitting low in the sky. We felt confident of our return trip because our last helpful VVV clerk had mapped our route cautiously back around The Hague. A clear shot to a hotel in Hoofddorp, so we thought.

Hoofddorp, with close proximity to the Amsterdam Holland Airport was a good choice for convenient accommodations, but not without a logistical struggle. Now late in the day, the heavy traffic with the unaccustomed canal crossings involving lift bridges, slowed our progress to a crawl. Dinner again would be late.

But somehow the tighter schedules we aimed for at the start of our trip now had a softer edge, and that seemed okay for Dad. I began to realize that this eighty-two-year-old, small-town, Midwestern guy accustomed to scheduled days, regular meals, and a cup of coffee for only $.25 including refills—also could be an easy-going, fun-loving traveler. Why was I so worried? After all, Russ Albrecht had always been an eager learner, curious, adaptive, clever, judicious, and above all, outgoing and positive. Why should any of that change because of age?

So now nearing eight o’clock as we finally sat down with our beers and his “brandy seven,” Dad joked and laughed and rallied in our travel mishaps, as well as our finds. And then he paid us the ultimate compliment: “You two sure put on a nice tour. Yah, couldn’t have asked for more. You betcha.”

My wish for a perfect trip really did come true.

Just down the street at Panekuken we found our dinner. I wrote in my journal, “Good, but very expensive.” That seemed appropriate for the occasion.

***

1944-1945: “In the summer of 1944, the War Department published a pamphlet entitled “Do You Want Your Wife to Work After the War?” Designed as one of a series of GI pamphlets which officers could use to provoke discussions and forums, the pamphlet tried to impress on its readers that women’s roles were changing, but the dominant voices were those that spoke against women’s working.”

No Ordinary Time, Doris Kearns Goodwin (Simon & Schuster, 1994)

Private Albrecht:

NO MAIL

When I went up to the Bulge on December 15th or somethin’ like that, they took us up and, of course, no mail. I didn’t get mail then. On Christmas Day I went to the hospital and I got into Paris, but they wouldn’t let me give the address of the hospital to send home so I could get some mail. So that length of time I didn’t have any mail. By the time I got back out of the hospital, my mail hadn’t caught up with me yet. It had been making the circuit. See, I was in the hospital in Paris for ten days in the big General Hospital, and then I got moved out to another hospital in Paris and I stayed there, I forget how long. But anyway, no mail. Finally, I tried to write the address of the hospital and they cut it out so when Lorraine got the letters, there was no chance of finding out just where I was. Well, then I went back up to the Front and they said, “Well, your mail will catch up to you.” But then I got hit and back to the hospital again. All this while that mail, I guess, was making the rounds but not getting to me. So then I got sent down to Nuremberg and from there to Reims, France.

On the second of July I got 104 letters! On the third I got 102, something like that—it was over 100! All these letters and someone had tied string around them, and Lorraine had been getting her letters back home with string around saying they had no way of finding me. Well, that made her mad, and she contacted the postmaster in Morgan but didn’t get a response. Then she called in to the State or wrote in, but nothing there. She kept getting letters back that she had written to me—but she was getting mine right along so she knew I was all right.

The last letter I got from her wasn’t the one I should have had. There was one I should have had before, but they didn’t always come quite in rotation. The last letter I had she was saying she hoped that Diane would heal up and wouldn’t have any ill effects and so forth . . . and I had no idea what in the heck had happened. I figured that she probably ran out in the street and got nicked by a car or something like that! I later learned that Diane rode her tricycle down the steps at our house and landed on her face.

But anyway, that was six months that I didn’t hear a word from anybody and then, like I say, on the second of July, I opened up that first 104 and got my Christmas packages, what few was there—they were all moldy, whatever was in them. They’d been in shipment that long. I didn’t know where they’d been. I didn’t open them all because the guys in my outfit, when they would see packages, they all helped you in a big way! They tore the first one open, and that’s one I got from my folks and it had Christmas candy in it. You know the old twist, the old Christmas mix in a cellophane bag—well, that had melted flat, the whole package was flat as a pancake and it looked just like bacon. That red in there made them streaks. The guys said, “Oh, man, you got bacon here!” and they ran to find something to fry it in. Then I got a hold of it. I said, “You don’t need to look for something to fry it in—that’s just hard candy that melted.”

Then Alice Rands, a neighbor from Morgan, sent me a box of fudge, because she knew I liked fudge—and the guys had opened that. By the time I saw what was in there, there was only one piece left for me! They had eaten all of it, and it was so moldy you couldn’t tell it was fudge, you know, just covered with mold—but down it all went. They didn’t pay much attention to it.

This was in Camp Chicago when I finally got the letters. One day they called me from the tent, and I went up to the Captain’s quarters—here was a fellow from the U.S. The Postmaster General of the United States got the letter from Lorraine really chewing him out for not getting my letters that I should have and so he sent a man over to find out just what the heck caused that so they wouldn’t have that happen again to somebody else. I suppose it probably did help.

1944 – Biggest thrill: letters and packages. (History of the 120th Infantry Regiment)

***

Thanksgiving Day 1945: President Truman’s Proclamation—“In this year of our victory, absolute and final, over German fascism and Japanese militarism; in this time of peace so long awaited, which we are determined with all the United Nations to make permanent; on this day of our abundance, strength, and achievement; let us give thanks to Almighty Providence for these exceeding blessings. We have won them with the courage and the blood of our soldiers, sailors, and airmen. We have won them by the sweat and ingenuity of our workers, farmers, engineers, and industrialists. We have won them with the devotion of our women and children. We have bought them with the treasure of our rich land. But above all, we have won them because we cherish freedom beyond riches and even more than life itself.”

www.presidency.ucsb.edu

Private Albrecht:

GOING HOME

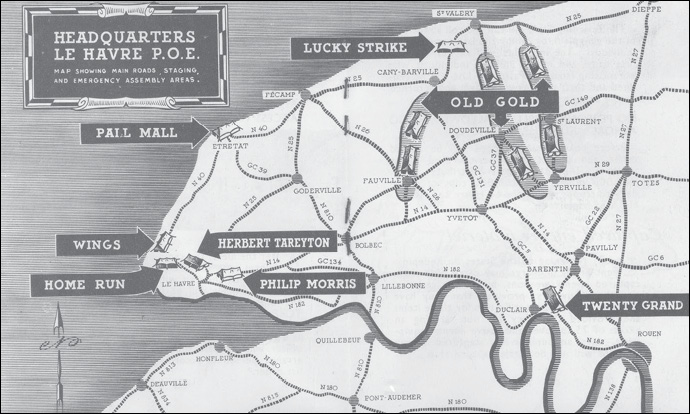

After Camp Vineyard, they sent us to Camp Herbert Tareyton—they had them all named by cigarettes—on the English Channel, down there by Le Havre. We were there a few days before we loaded.

1945 – The “Cigarette” camps—“Map showing main roads, staging and emergency assembly areas,” Your staging for the States, Headquarters, Le Havre, Port of Embarkation, Transportation Corps, U.S. Army. (Author’s Collection)

Our ship was called the U.S. Wakefield. It was a big ship—held 7,000 of us on there anyway. It was kind of odd when we were going up the gangplank—everybody had to have their sleeve rolled up and you got a flu shot, whether you wanted it or not. They said we were guinea pigs, that it was a flu serum. They were going to see how it was going to work.

Of course, you couldn’t have any weapons on you or along with you unless you had your permit for them. I had a permit for a French forty-four revolver and then a bunch of knives. I also had a German flare pistol that I would liked to have taken home, but I didn’t have a permit for it. They let you know before you went on that if you had any of that stuff, and if you didn’t have a permit, not only would that be taken away but you’d get off the boat and wait for a different one. So of course everybody was throwing that junk in the English Channel there—getting’ rid of it if you had more than you should have. We never did get searched. We could have had a whole barracks bag full, and it wouldn’t have made much difference.

1945 – Loading the Wakefield. (Author’s Collection)

We started for home. It was real, real rough in the Channel. The weather was bad and rougher than the dickens. We just got started, and I asked a sailor, “Holy smokes! This is really a rough old sea, isn’t it?”

“Oh, man,” he said, “you haven’t seen anything. You wait about two and a half days and then we’ll be right smack in the middle of a good end of November North Sea storm—and you’ll know what a storm is like!”

And boy, we sure did—holy mackerel! But for some reason I never had the slightest feeling of gettin’ sick. My appetite was big, and everybody was throwing up all over the place. Where we slept I had a top bunk so I wouldn’t get thrown up on. The floor was full, the walls were full, the stairway was full. No matter where you looked, somebody had thrown up. All the poor guys were sicker than dogs.

1944 – Private Albrecht. (Author’s Collection)

Only seven of us they would let out on the deck, and that’s if we had a rope around us. The first railing on the deck was sixty feet above the water and the ship would lay over on its side so that the waves came up on that—so you have an idea. And you’d swear it never was going to straighten up again . . . but it would. We had that, oh, half way across the Atlantic, and then it started to calm down and we got out of that storm. They told us one night that in so many hours then, “We’re going to hit the Gulf Stream.”

“Well, so what?”

They said, “You’ll find out when you get there.”

All of a sudden it got quiet and the air got warm and nice. You couldn’t believe that you were off that rough stuff, but they also told us that we wouldn’t be in it very long. “We’ll be going right straight through it—and when we get through it, we’ll be back in our rough weather again.”

And that’s exactly the way it panned out. Now how that works I have no idea but it did. Then a little later, it calmed down, and it was better seas although it was raining when we came into Boston, I remember that.

All of a sudden somebody hollered, “There’s the U.S.A.!” and we were all up on board there looking over the edge . . . and there it was! Boy that really looked good, I’ll tell you that!

Boston is where we landed. They had a camp right near the docks. It had sort of barracks there, and we went in there, I think just overnight. To start, when we got in, everybody went in the mess hall. By the way—we got in there on Thanksgiving, the end of November, that was Roosevelt’s Thanksgiving Day. They had turkey and all the stuff, you know—boy that was good! But of course, a lot of the guys still had that effect from being on the boat, and they still couldn’t eat. But I could.

Then we all figured, “Oh, boy, you know, we could get a good haircut now, something in America, and they told us they had a bunch of barbers.” They were civilian barbers, not Army barbers. They were in the camp, and they charged their regular fees, whatever it was, but it was high priced—we didn’t give a rip. We came in there, and they said, “You want the works?”

“Yup, yup.” That meant a shampoo and everything else with a haircut. I guarantee you I went in, and I said, “Ya, I want the works.” I had my hair washed and cut and trimmed, all lined up, and dried—at least it was supposed to be—and I betcha it didn’t take five minutes! They charged like Sam Hill. You went out of there dripping down your neck, and the hair looked like Sam Hill. Boy, I tell you, those guys made a fortune in there. You get 7,000 guys coming in there and all want their hair washed and, why, holy mackerel, if that wasn’t a screwed up mess!

Then in Boston we got on a train—we called it the Milk Train. They stopped about every doggone stop. We went, I think, until Buffalo, New York, and there we crossed and went up into Canada. I remember some of the Canadian towns were like Paris, London, and so forth. And then I don’t remember where in the heck we came back down into the States but finally wound up at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin—that’s where we were discharged.

At Camp McCoy some fella, a young guy, said his dad who lived in Minneapolis was coming to get him. I got in with him and he wanted to know if I knew the address in Minneapolis—you see, my brother Roy and Dad were going to be down at Uncle Al’s to pick me up. We drove and got into Minneapolis, and he drove me right up to their place. I went over to Uncle Al’s, and then Roy and Dad, they met me there. It wasn’t too long, and then we started for home.

They warned us on the boat when we were coming into the U.S., “When you guys get into Boston now, don’t all rush for the phone to call your mother to let her know you’re here—unless your mother is young.” They had so many that all of a sudden when they landed they’d call their mother, probably you know, older, and say, “Here I am!” and ‘boom’ they dropped over with a heart attack.

So I didn’t do any calling at all. In fact, they even suggested like as soon as you get home, just don’t barge right in to your folks. Let them know ahead of time that you’re home and you’ll probably be there the next day. That’s what I did with Mother. Of course, Lorraine—there I went right in—Dad and Roy dropped me off at our house. Then the next day I went over to see Mother.

Note: A final story about Russ’s first day back in Morgan wasn’t included in the taping session. When asked about it in the fall of 2003, when Russ was ninety-two years old and in failing health, he simply recalled:

“I had the two girls—each had a flag—walking on each side of me, walking downtown.”

***

1945: The original Pledge of Allegiance was written by Francis Bellamy in 1862. “No form of the Pledge received official recognition by Congress until June 22, 1942, when the Pledge was formally included in the U.S. Flag Code. The official name of ‘The Pledge of Allegiance’ was adopted in 1945. The last change in language came on Flag Day, 1954 when Congress passed a law which added the words ‘under God’ after ‘one nation.’”

www.legion.org