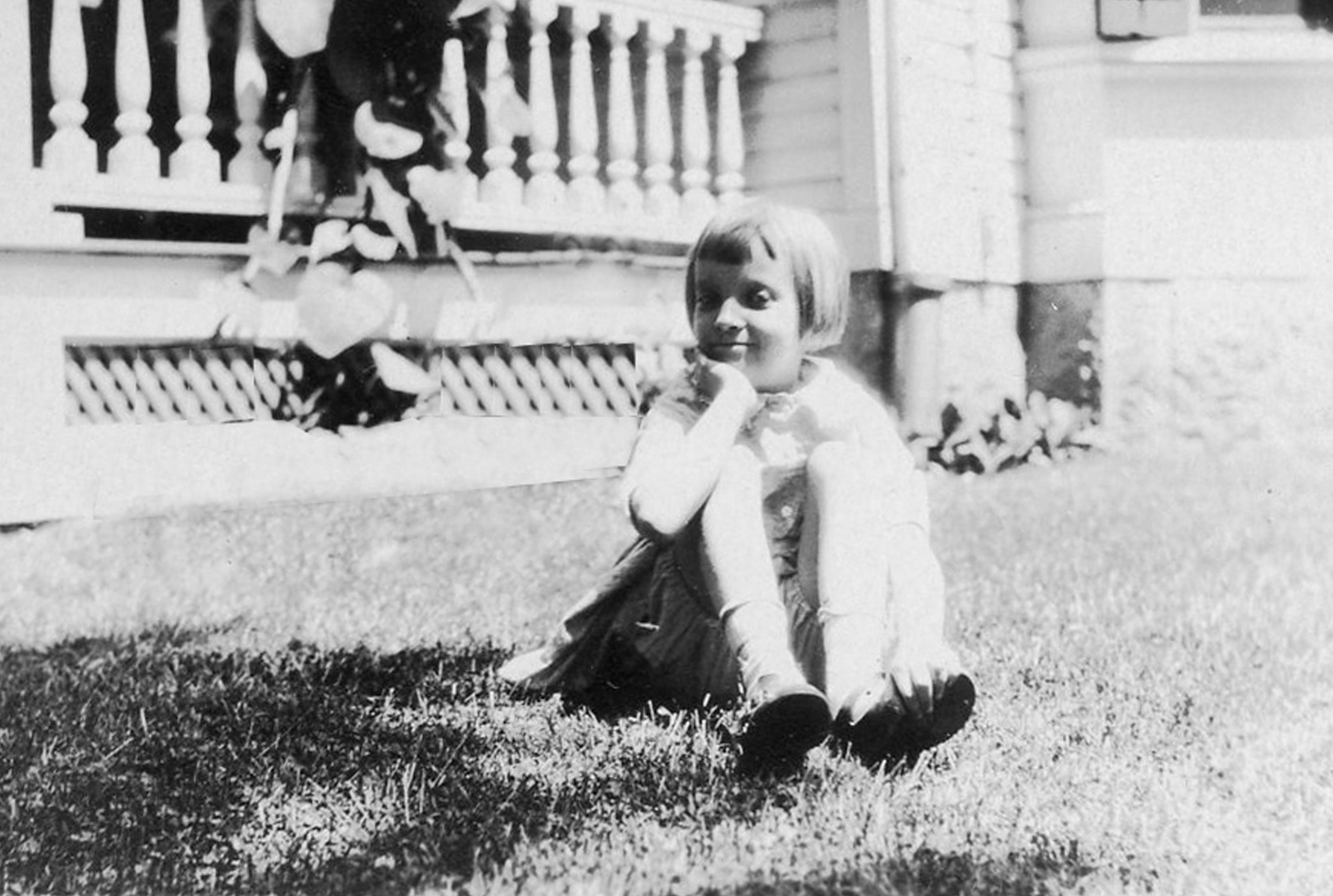

Madeleine, circa 1924

Madeleine enjoyed school in the early grades, but things changed in the fourth grade, when she switched schools, and going to class started to become a painful, diminishing experience. With one leg slightly shorter than the other, she didn’t have the same athletic prowess as her classmates and so was always picked last for any team. She quickly gained a reputation for being both clumsy and stupid, for she was shy and reticent. Her peers treated her badly, and her teachers graded her to their own expectations instead of Madeleine’s actual performance. Thus Madeleine learned that making an effort for the teacher simply wasn’t worth it. When she went home, instead of doing homework, she turned to her own reading and writing. Grandfather Bion sent her books and magazines, and she wrote stories. After all, that’s what her father did. She also wrote poetry.

One day that first year at her new school, Madeleine’s French teacher refused to let her go to the bathroom even though she asked repeatedly to be excused. And so she wet her pants. When questioned by Mado and the headmistress, the teacher defended herself by lying, saying that Madeleine had never asked to be excused. But Mado believed Madeleine, and that was a comfort, although watching an adult lie and get away with it was devastating to Madeleine.

The next year, in fifth grade, there was a poetry contest that was open to the entire school and judged blindly. Madeleine entered one of her poems. When it won and she was revealed as the writer, her teacher insisted that Madeleine couldn’t possibly have written such a good poem and accused her of plagiarism. Outraged and indignant, Mado took samples of Madeleine’s poetry to the school and showed them to both the headmistress and the teacher, who was forced to concede that Madeleine was a good enough writer to have written that poem after all.

Madeleine’s prize poem, published in the school literary magazine, May 1929

Madeleine, circa 1926

When Madeleine wasn’t reading and writing after school, she was taking art and piano lessons. She was also forced to take dance lessons, which she detested so much that her instructors proclaimed she was “unteachable.” It was a pretty miserable—as well as formative—few years: from then on, Madeleine carried with her the feeling that she was awkward, inadequate, unattractive, and stupid, feelings that made her acutely grateful for any acts of kindness and affection that she did receive from others.

Madeleine did have one friend with whom she played occasionally. April Warburg, the daughter of a wealthy banker, was as much of an outcast at school as Madeleine was, and just as dreamy. Sometimes Madeleine would go over to April’s house, a mansion on Fifth Avenue. April’s parents weren’t around, but there were multiple servants—butlers, ladies’ maids, governesses—and Madeleine was struck by the different kind of isolation April endured: one in which she was not alone, but lonely. She saw how removed her friend was from her parents and from affection of any kind, and she was thankful for her own relatively close relationship with her mother and father.

Then Madeleine’s father’s health started to fail. When he was in the army, his unit had been gassed by enemy forces during the war, and the effects of the mustard gas had left him prone to severe and life-threatening bouts of pneumonia. He also smoked and drank heavily, which exacerbated his fits of coughing and his headaches. Mado was worried about Charles’s health, but he seemed more concerned with the fact that his writing work was drying up—it was difficult to support a family as a freelance journalist, and his fiction wasn’t selling as it had before the war. He caught pneumonia and was warned that he should find a more healthy place to live: the dirty, smoggy air of New York City might kill him. Could they possibly leave the city? Their life was there. If it was difficult getting writing assignments in New York, how much harder would it be elsewhere?

And then the stock market crashed in October 1929, and a great many people were in financial trouble, including Madeleine’s parents. They decided they had no other choice: the summer after Madeleine finished sixth grade, they packed their clothes; put their furniture, piano, dishes, and silver into storage; and moved to the French Alps, where there was clean mountain air and where, at that time, it would be less expensive to live.