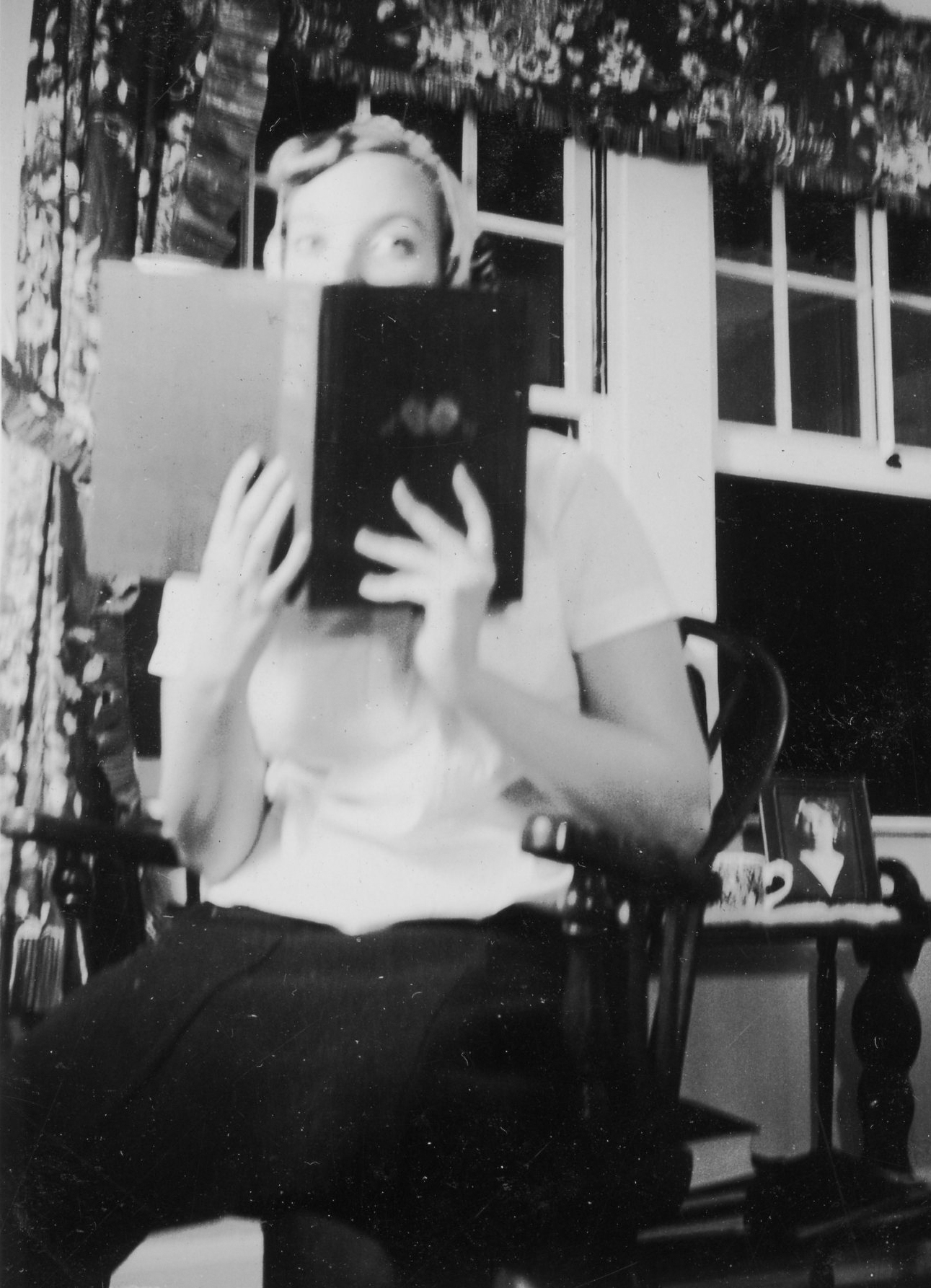

Madeleine, circa 1938

In the summer of 1937, after her high school graduation, Madeleine and her mother went on a trip together. Madeleine still didn’t know what she would be doing in the fall, but it didn’t seem to bother her too much.

What a thrill it is to get on a train with no definite idea of how long one is to be gone, or where one is to go, even if the first part of the journey is over very familiar land … College Boards are over, but whether or not they are passed I can’t say yet; and I have the summer and the world ahead of me!

Mado and Madeleine spent several days in New York City with old friends who took them to the theater and concerts. Mrs. O, with whom Madeleine had corresponded over the years, visited, too, and Madeleine was very happy to see her. On July 9, Madeleine and her mother set sail for England and France, where they would visit family and some of their old haunts. Madeleine also seemed to have gotten over her aversion to dancing.

I danced quite a bit with the ship’s doctor last night. He is an awfully good dancer. I danced with him and another man whose name I don’t know—and he was introduced to me!—this evening, but mainly with the doctor. He tried to kiss me, but otherwise he was all right. We had balloons and it was all very gay.

Madeleine and Mado had a good time in London, but at the end of July, when Madeleine found out that she had been accepted to Smith, she started to have a wonderful time. Smith wouldn’t start until the end of September. Mado selflessly insisted that she attend. Madeleine knew it would be difficult to leave her mother and live in faraway Massachusetts, but her experience at boarding schools had made her independent. She knew she was ready.

Madeleine, circa 1939

She liked Smith. Her friend Cavada Humphrey from Ashley Hall was also there, and during her first year she made new friends and enjoyed her classes. As at Ashley Hall, Madeleine and all her friends had nicknames for each other. For her time at Smith, Madeleine was referred to as “Tony.”

There was sadness, too, not only at being so much farther away from her mother than she had been at Ashley Hall, but also at missing her father, especially on her birthday.

Today I am nineteen. I feel very, very old, and also very immature and adolescent … There was nothing from Father. Last year at my birthday I was still numb—I didn’t quite realize things yet—and I was with mother and there were so many things from everybody that I didn’t really miss him so much on this particular day—Oh, Father—

Her journal writing slowed down considerably in college, but she wrote daily postcards to her mother.

Madeleine’s postcards to her mother

February 2, 1938

Mum darling,

The English exam is tomorrow and I do hope I can get a decent mark in it. Oh! but I’ll be relieved when it’s over and I’ll be all through! This Sunday I’ll really write you a letter.

It’s the most wonderful weather—cold and crisp. We’ve been going on nickle walks for our exercise. You know—at each corner you flip a nickle—heads left, tails right. It’s lots of fun and we’ve got to some awfully queer out of the way places. Must stop now and get back to the Elegy, which is where I am at this point. —M.

When she did write in her journal, often during frequent trips to the infirmary with a cold or flu, she wrote about her past, describing what life had been like at Châtelard or at Ashley Hall, or she wrote character sketches of other young women at Smith. She also had class papers to do, and she worked on her stories and poems. Still, she made observations in her journal about writing.

I made a discovery yesterday. I don’t suppose it’s an original sort of discovery at all, but at any rate, I found it for myself. When you write anything—a poem or a story—it’s yours only as long as only you know anything about it. As soon as anybody reads it, it becomes partly theirs, too. They put things into it that you never thought of, and they don’t see many things that you thought plain.

Her short stories were often based on incidents in her own life, moments when she had an epiphany or had to resolve some kind of conflict. She wrote about that Christmas vacation from Châtelard that she would continue to revisit throughout her life, when her parents were wrapped up in their own worries and sadness. When Mado read the short story Madeleine proudly showed her, Madeleine was shocked when Mado burst into tears. Madeleine hadn’t realized how much she had been able to capture in her writing, and it gave her her first inkling that her writing knew more than she did.

She met professors at Smith who helped her hone her craft and whose lessons remained with her throughout her life. Esther Cloudman Dunn taught Shakespeare and drove home the powerful thought that the playwright always started with an attention-getter: a storm, a battle, a fistfight. Professor Dunn also confessed that there was one Shakespearean play she had never read because she couldn’t bear to have read all of his works.

Another professor, Mary Ellen Chase, taught the novel. On the first day of the survey class she handed out a one-hundred-question quiz about Jane Eyre with questions like “What color dress was Jane Eyre wearing when she met Mr. Rochester?” Indignant, Madeleine turned the page over and wrote: “I don’t know what color the dress was, but I know what the book is about.” She then wrote an essay instead of taking the quiz. Professor Chase handed the quiz back to her with the remark “Take no more quizzes.”

Professor Chase, in a college-wide address, once divided all works of literature into three categories, “major, minor, and mediocre.” Her New England accent made it sound like “majah, minah, and mediocah,” and that phrase became a running joke on campus. But it wasn’t entirely a laughing matter for Madeleine or her classmates. They all aspired to being “majah” and feared being judged “mediocah.”

Leonard Ehrlich taught creative writing, and although Smith would allow only one creative writing class to be taken for credit, Madeleine studied with him multiple semesters, not caring about the credit. He encouraged her and thought she had great promise as a writer. Hearing his words, she felt both vindicated—“I do have talent!”—and terrified—“What if I can’t live up to his expectations?” But under Professor Ehrlich’s tutelage she wrote many short stories, some of which were published in Smith’s literary journals, and some of which she reworked later into scenes in her novels.

She didn’t respond positively to all her writing teachers: when one commented with a Freudian interpretation on a story of hers, she dropped the course.

She met Marie Donnet and they became best friends.

Madeleine and Marie, circa 1939

They were both active in the theater department. Marie was an actor and director, and in some ways the opposite of Madeleine: outgoing, confident, and charismatic. They seemed to bring out the best in each other, and they accomplished a great deal on campus. Together, they started French House (a French-speaking dormitory), produced multiple plays, and had dreams of moving to New York together and making their mark on the theater. While Madeleine mostly concentrated on writing, she was also happy to take small parts onstage. Marie had much more of a stage presence, and Madeleine was as captivated with her as everyone else was. In turn, Marie was steadfast in her support of Madeleine as a writer.

Smith College Weekly, October 18, 1939

Madeleine was active in various student publications, reviving the campus literary magazine, Opinion, and then editing the Smith College Monthly. A classmate and colleague named Bettye Goldstein was also on the staff of both publications. Bettye later became famous as Betty Friedan, author of the feminist classic The Feminine Mystique.

Madeleine adapted some of her short stories into plays, and was constantly revising and reenvisioning her work. Both Madeleine and Marie were determined to be, as Professor Chase would say, a “majah” force in the theater. Marie had met Eva Le Gallienne, founder of New York’s Civic Repertory Theatre and the most famous actress and director of the day, and found there was a chance that Miss LeG (as everyone referred to her) would come to Smith to direct a student play. Marie sent her Madeleine’s play A Weekend in the Country. Although the visit fell through, Miss LeG encouraged Marie and Madeleine to look her up when they moved to New York City after college.

Eva Le Gallienne, circa 1930–40

Marie and Madeleine were giddy with excitement. They made plans to have Miss LeG produce Madeleine’s next, and better, play on Broadway.