‘… I read about Tamoxifen. Nobody really knew much about it and I spoke with a young medical scientist at Flinders University Medical Centre who talked to me over the phone. He was such a great advocate for this new treatment that I decided that yes, that’s what I’d do.’

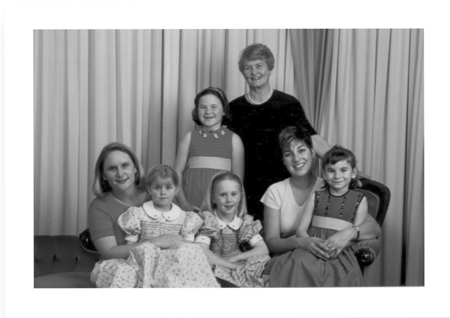

Jocelyn Newman AO is in Queensland for the Easter school holidays, visiting her son Campbell, Brisbane’s Lord Mayor, and spending precious time with her two granddaughters and their mum, Lisa. She is relaxed, carefree and at peace with the world—a far cry from the tumultuous times in 1993 and 1994 when Jocelyn faced not one but two bouts of cancer within six months.

‘In 1993, I was a fairly new Tasmanian Senator in the Australian Parliament. I was happily married, with two adult children, when I was diagnosed with uterine cancer. Fortunately, this was caught in time and after a hysterectomy I recovered and was ready to get back to work,’ says Jocelyn. ‘At the time I admit to thinking to myself, “How do I deal with that?” But it was okay and I got on with life.’

Within six months Jocelyn had what she calls ‘my second warning’.

‘Funnily enough, looking back, what I remember about being diagnosed with breast cancer was the press conference I did in Parliament House. It was one of those Sunday ones, ready for the Monday papers, and it was one of the hardest things I have ever done in my life,’ she says.

She was now a Shadow Minister under Liberal leader John Hewson and she announced that she had breast cancer and told the public that she was stepping down from the Shadow Ministry. ‘I just can’t give my all to fighting the disease and staying on in Parliament and honourably doing the job of Shadow Minister.’

The timing was not good. The following Monday, a significant Liberal Party meeting was held and Jocelyn hoped that ‘the solemnity of my announcement and the seriousness of the disease I was fighting’ would help unify the factional fighting within the party under a stable leadership. ‘Sadly, that didn’t happen,’ she adds.

Jocelyn always had regular mammograms and it was during a time between these when she felt the lump in her left breast. It was quickly diagnosed as a tumour. ‘Years previously, I had also detected a small lump, had it tested and it was found to be just a calcified spot. But blow me down if this cancer wasn’t in exactly that same spot.

‘When they confirmed it was cancer I went cold, my brain froze and, coming on top of the other cancer, I did feel I’d had a hard run,’ she confesses.

Jocelyn wasn’t entirely surprised at being diagnosed with breast cancer. Both her mother and her grandmother and, she has since discovered, other family members had breast cancer. ‘So it was something that you almost expected but you hoped to God that it wouldn’t happen. However, none of my family have ever died from the disease so that gives me hope.’

Nevertheless, this doesn’t mean that Jocelyn doesn’t worry for her daughter and her four granddaughters. ‘We specialise in women in our family,’ she jokes, ‘so it is an ongoing concern. I also know that my son could be at risk, because it isn’t widely known that men also get this disease.’

As a consequence of her public profile, Jocelyn received hundreds of letters of support from all around Australia. ‘But really the saddest letters were from the men who felt that there was little recognition or support for men with breast cancer. Many of them felt very uncomfortable about getting help.’

After standing down in Canberra, Jocelyn returned to Tasmania and ‘went through the mill’.

She had a mastectomy—‘Off with her head!’ she jokes,—and full axillary clearance, which resulted in lymphoedema in her arm. She shrugs and says, ‘The same problem is in my leg from the previous cancer. So now I have enough, thank you! I wear trousers and I have to keep moving.

‘Even when I returned to Parliament I used to sit back in my seat and do arm stretching exercises for much of the day—just like the blokes sitting back in their chairs. No one knew until I retired and then I told them what I’d been doing!’ she laughs.

In many ways Jocelyn’s uterine cancer overshadowed her breast cancer diagnosis. When she had a hysterectomy, the family gathered quickly. Jocelyn recalls bursting into tears and sobbing, ‘I feel so mutilated, so mutilated.’ Then, when she was faced with a mastectomy, she and her family were extremely worried about how they would cope with this second ‘mutilation’.

‘I am sure the mastectomy was the sensible thing to do, but nowadays, with lumpectomies the go, I wouldn’t have had to have it. I do envy people these days who still have two breasts.

Yet she still feels intense disappointment that the surgeon would not do a double mastectomy. ‘With my family history, I pleaded with my surgeon to do a double mastectomy. Being flat-chested was no big deal. Being lopsided was a horrible look. I think he was a man who expected women to have breasts. His attitude was: if this breast hasn’t had cancer in it—yet—then we can’t take it off.’ But I would have preferred to have been flat-chested. That would have been simple, cheap and ‘no worries’.

Once she’d recovered from her surgery, Jocelyn was advised by oncologists to go through chemotherapy. She thought it seemed very daunting and too demanding, and self-deprecatingly says, ‘I was gutless; I was looking for an easy option.’

She had already told her doctors categorically that—having had traumatic experiences during her uterine cancer treatments—radiotherapy was not an alternative. ‘I didn’t like those options. Can I have another menu please?’ she had asked.

Although she knew what she didn’t want, she had no idea what other choices were available for her.

‘At the very time I was lying in hospital in Launceston, the Federal Parliament was having an inquiry into breast cancer. I contacted Trish Worth, a colleague of mine in the House of Reps, and asked her to let me know who the most impressive witnesses were, and what was the best evidence of treatment. So daily, as they came off the press, I read all the transcripts and I read about Tamoxifen. Nobody really knew much about it. I spoke with a young medical scientist at Flinders University Medical Centre who talked to me over the phone. He was such a great advocate for this new treatment that I decided that yes, that’s what I’d do.’

Tamoxifen was new in those days and although her doctors were not adverse to that as the only treatment, they didn’t want to be responsible should things go wrong. Jocelyn took control of her health and said, ‘No—that’s what I want!’

‘Some people thought I was crazy—because it was new and because I didn’t have any other treatments. But I have never been sorry. Maybe, looking back, I may have wondered if I was being “a little too smart by half” and thought, “Will I be sorry?”’

When Jocelyn went for her five-year check-up, she asked to remain on the drug for another two years. ‘This was the lucky charm in my pocket,’ she grins. Even now she follows all of the new and exciting advances in medication and inside thinks to herself, ‘There go I.’

When I ask how her family and friends coped with her breast cancer diagnosis, she candidly answers, ‘I have no idea—I really haven’t. My husband was wonderful. I was treated beautifully by him. He ran the home, did the cooking, but because he had retired he was already doing much of that. As I was a Minister in Parliament, he kept the home going while I was away in Canberra and so, with my diagnosis, nothing much changed.

‘The children had left home at the time and although they didn’t immediately fly back to Tasmania to my bedside, they are, and were during that time, very good rocks to stand on,’ she says proudly. On reflection, and prompted by her daughter-in-law, Jocelyn recalls the family did come down to make sure she was coping—‘But they’d done it once before and, for us all, the breast cancer wasn’t nearly as scary. They’d already been through everything! We’re a phlegmatic family really, aren’t we?’

Whilst friends are often the cornerstone of emotional support during times of illness, Jocelyn explains that her situation was unusual and different from most. As an army wife, she had lived in many different towns and cities, so true friends were scattered all around Australia. Her longtime friends from her early years in Melbourne were compassionate—but not in the same State as her.

She also rationalises that when she moved into Parliament, she met and was friendly with lots and lots of people over the whole of Tasmania but she didn’t have many close friends. ‘People do gossip about you. There is no privacy. so you protect yourself by not having too many people who are very close, especially in the home situation. But it wasn’ t hard because I have such a loving family. We just closed ranks around the wounded bird—that was all I needed.’

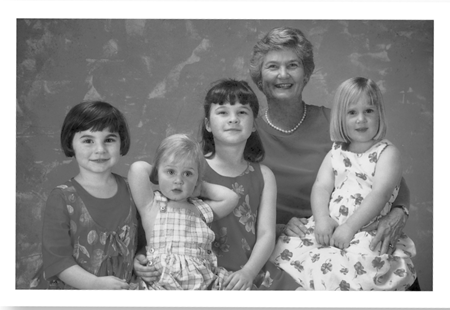

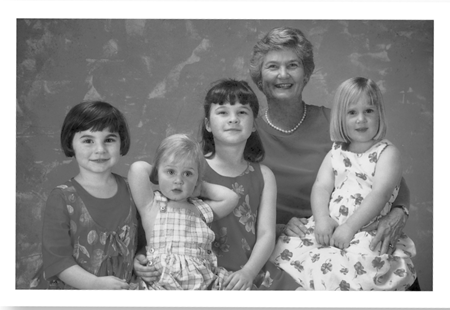

Jocelyn with her daughter and daughter-in-law, and her granddaughters

She does, however, feel for those who are not so loved and supported. ‘I feel deep sympathy for those women who are on their own or become alone when their husbands or partners walk out. I just don’t know how they cope.’

She also had enormous public support and felt very touched by the boxes and boxes of letters that people sent her during her illness. ‘I have kept them all—that sort of kindness I’ve never wanted to throw away.’

Nevertheless, Jocelyn is a self-proclaimed independent and dogged person and she knew that if she was to recover, she was the only person who could make it happen. ‘For pity sake,’ she told herself, ‘get home and get on with whatever is left of your life!’ And she did.

When asked about how she felt when faced with death and dying, she is thoughtful. After deep consideration, she admits that ‘It was too long ago now. So much has happened in my life since then that my emotions back in 1994 have been washed away.

‘Having had two serious operations to deal with life-threatening cancers so close together, an awful lot of those thoughts and emotions happened at the time of the first cancer,’ she suggests. ‘That was my first instance of facing my own mortality and I think after that I had a more pragmatic view with the breast cancer, thinking that I’d been okay then, so let’s see what this brings.’

Jocelyn acknowledges that while she doesn’t dwell on it, she is more prone to thinking that maybe the breast cancer may return. And she is certainly aware of her own mortality—but in a positive way. ‘I just get out and do things now; I don’t ask why not, because you are a long time dead.’

And her full life is indeed testimony to that positive attitude.

The period immediately following her recovery from the breast cancer surgery was one of the best times for Jocelyn in her political career. ‘I went back to Parliament after a few months, and the new leader of the Opposition, Alexander Downer, asked me to come back on the front bench. I told him I was going to be a little sensible and quietly look after myself. He then said to me, “What if I said it was as Shadow Minister for Defence?” I instantly replied, “Done!”

‘That was my dream. I’d been Shadow Minister of the junior portfolio of Defence and had written policies for numerous departments, but this was what I really wanted to do,’ she says enthusiastically, then wryly adds, ‘When John Howard got into government, he did appoint me as a Minister—but it was for Social Security!’

Almost immediately after her diagnosis, Jocelyn became a stalwart champion in helping those who have been diagnosed with breast cancer. ‘Being a Parliamentarian, I found I could use my position to help the cause. So I tried to do what I could when I had the opportunity.’

Since retiring from Federal Parliament, Jocelyn is very active in her support for the Breast Cancer Network of Australia (BCNA). She says her life is filled with good humour and that everything she does with BCNA turns into a laugh. ‘We have all had breast cancer and so we are sisters under the skin. It is a very nice feeling when you have a National Conference and we all get together, compare notes and generally have fun.’

As well as finding her work with the Network enjoyable, Jocelyn says it is ‘truly inspirational’. She becomes especially emotional when she speaks of the National Field of Women held in Melbourne at the MCG. ‘Before the big AFL match we were on the field, helicopters were circling overhead, and all of us—men, women and children—felt such a buzz. Here we were standing in the middle of the MCG in pink, creating a giant pink lady silhouette—getting the message about breast cancer out to not only those at the ground, but to the millions watching TV around the country. It was amazing.

‘I couldn’t stay after the display and savour the feeling because I had to catch the last plane back to Canberra. So I raced to the airport. I was running down the concourse when a young man stopped me and said, “I rang up and gave money to you guys.” Another couple added they, too, had donated, and when I got onto the plane the stewardess told me she’d wanted to go to the MCG but couldn’t change her roster. Of course, I was still in my hot-pink poncho! These were three very touching take-outs from that night. I still remember them clearly because it was extremely emotional for everyone—spectators and participants,’ she says.

As an advocate for the BCNA, Jocelyn is very proud of the support given to women—all around Australia and beyond. One example she recounts is of being on Norfolk Island and speaking to the CWA group about the Breast Cancer Network and its achievements. ‘I told them about meeting a woman in Philadelphia a few months earlier. We got talking and she told me she worked for breast cancer. I told her I did, too, and I shared with her some of our successes here in Australia. I gave her a copy of the My Journey Kit. She took that back with her to the US, where the community workers were so impressed with its practical value to women that they were planning to produce a similar kit in America.’

On Breast Cancer Day in 2006, Jocelyn went to the annual remembrance ceremony at the Calvary Hospital in Canberra. She pauses, struggling with her emotions as she remembers the day. ‘I sat down beside this lovely young couple with their toddler son. When the speaker was introduced, the young lady got up to speak about her diagnosis with breast cancer. That episode really got to me more than my own cancer. I still feel churned up thinking of that young woman and her very young family and hope that everything is okay.’

Having twice looked death in the face, Jocelyn has kept faith with her maxim of squeezing every ounce out of her life. She recently travelled across the world, spending a month sailing across the seas as a passenger in a container ship. ‘After Queensland friends had experienced travelling overseas this way, they urged me on, saying I had the temperament. And so I just had to do it. It took me two years to find a ship going to where I wanted to travel and at the right time. I was the only passenger—indeed, the only woman on board—and then to make it even more interesting, the crew spoke almost no English. All of that contributed to making it such an amazing experience,’ she beams.

‘That first trip took me from the east coast of America to Cartegena in Colombia, South America then through the Panama Canal across the Pacific to New Zealand and home. I loved it so much I took another trip from Australia through the Suez Canal to the United Kingdom. Then my third container ship took me from Tokyo down the east coast of Asia to Singapore.’

I ask why she travels this way and not enjoying the luxury of cruise ships. Jocelyn says simply, ‘The trips are peaceful, not very expensive, and hardly any passengers to bother me! The crews are very nice, the food is simple and there are books, flying fish, birds and denizens of the deep to keep you alert!’

The interview ends, and we walk down the street together. Jocelyn is about to head off on another little adventure—this time with granddaughters in tow—to look over Brisbane city from the newly finished council building. She is relishing the prospect of spending time with her family. Suddenly she stops and tells me, ‘Go and talk to some “stars”; I’m just an ex-pollie. Talk to stars whose stories will inspire.’

But to my mind, this petite former senator, who has put the nightmare of cancer behind her and is actively working with breast cancer networks, is a star.