Solomon Islands, August 1942. This dramatic picture shows the Guadalcanal landing, which was followed by six months of grueling fighting. (Bettmann/Corbis)

Guadalcanal was the first American amphibious counteroffensive of World War II. It was on this virtually unheard of island that the Americans shattered the myth of Japanese invincibility in the Pacific. Although the battles of Coral Sea and Midway are described as turning-point battles, it was at Guadalcanal that the Japanese war machine truly ground to a halt. The battle for Guadalcanal was a unique battle for many reasons. Both the American and Japanese forces fought at the farthest end of their supply lines. The battle itself would be among the longest in duration of the Pacific campaign. It would take six months of fierce and savage fighting in difficult terrain, testing the endurance of both sides, before the Japanese were driven off the island.

Ship losses off Guadalcanal, comparable to those suffered later off the Philippines and Okinawa, were so great that the waters along the north coast of Guadalcanal would become known as “Iron Bottom Sound” – a name that continues to this day. The bulk of the fighting was endured by the US Navy and the Marine Corps. However, US Army forces contributed significantly to the latter stages.

The Japanese advance had taken them to New Guinea and the Solomon Islands before pushing south and seizing Tulagi and Guadalcanal, where they began the construction of an airfield. The US was aware that the Japanese advance in the Pacific threatened the communications lifeline to Australia. Furthermore, American bases that lay in the path of the Japanese advance would be endangered. The Joint Chiefs of Staff concluded that an American offensive in the Pacific was now a matter of necessity. Once it was determined that the Japanese were constructing an airfield on Guadalcanal, the newly formed 1st Marine Division was given the mission of seizing that island.

The Japanese began construction of an airfield on Guadalcanal in mid-July 1942, with completion estimated by mid-August. According to Japanese documents captured later, the objective of capturing Tulagi in the Solomon Islands and building an airfield on Guadalcanal was to protect their flank while they were carrying out their main attack on Port Moresby, New Guinea. The secondary objective was to secure a favorable base of operations to move south through New Caledonia to attack Australia. This attack was to take place after the capture of New Guinea.

The landing on Tulagi was made on the beach just south of the golf course by the Marines of the 1st Raider Battalion, followed by the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines. The Raiders then moved west and the 5th Marines moved east to capture the island. The date of the photo, May 17, 1942, indicates that it is an early intelligence photo and was probably used to plan the assault. (USMC)

The American plan for the invasion of Guadalcanal began with inter-service rivalries. After the battle of the Coral Sea, in early May 1942, General Douglas MacArthur, Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area (CINCSWPA), realized that the Japanese would eventually attempt to sever the lines of communication between Hawaii and Australia. He felt that a Japanese attack on New Guinea was inevitable. To prevent such an attack he wanted to take the offensive against the Japanese in the New Britain-New Ireland areas. An attack of this nature would force the Japanese out of the region and back to Truk, north of New Guinea. MacArthur’s plan found favor with General George C. Marshall, US Army Chief of Staff. However, MacArthur did not have the resources available to launch such an offensive. Further, he had no troops under his command that had any experience of amphibious warfare. Simultaneously, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC) and Pacific Ocean Area (CINCPOA), was contemplating a strike on Tulagi, a plan that found favor with Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations. However, King felt that the immediate objectives should be in the Solomon and Santa Cruz Islands, with the ultimate objective in the New Guinea and New Britain areas. Nor could either side decide on an operation commander as and when an attack plan was formulated.

At the end of June the Joint Chiefs of Staff finally agreed on a compromise plan. It called for Admiral Robert Ghormley to command the Tulagi portion of the upcoming offensive; thereafter General MacArthur would command the advance to Rabaul. The American Navy with the Marine Corps would attack, seize, and defend Tulagi, Guadalcanal, and the surrounding area, while MacArthur made a parallel advance on New Guinea. Both drives would aim at Rabaul. The boundary between Southwest Pacific Area and the South Pacific Area was moved to reflect this, and South Pacific Forces were given the go-ahead to initiate planning. Ghormley in turn contacted Major-General Alexander A. Vandegrift, the Commanding General, 1st Marine Division (reinforced), to tell him that his division would spearhead the amphibious assault, scheduled to take place on August 1, 1942.

For General Vandegrift the problems were just beginning. He had not expected to go into combat until after January 1943. Only a third of his division was at their new base in Wellington, New Zealand; a third was still at sea; and the other third had been detached to garrison Samoa. In little less than a month Vandegrift would have to prepare operational and logistical plans, sail from Wellington to the Fiji Islands for an amphibious rehearsal, and then sail to the Solomon Islands to drive out the Japanese. In addition, there was limited available intelligence on the objective.

Realizing the enormity of the task ahead. Vandegrift asked for an extension of the invasion date. He was given one week: the amphibious assault would take place on August 7, 1942. There would be no further postponements, for the Japanese had most of the airfield completed.

The grouping of the Marines for the operation was based on intelligence estimates of Japanese forces in the area. It was estimated that of the 8,400 Japanese believed in the area, 1,400 were on Tulagi and its neighboring islands. The remaining 7,000 were thought to be on Guadalcanal, but this later turned out to be an erroneous estimate; only about half that number were there. It was anticipated that Tulagi would be the more difficult of the two amphibious objectives. The Marines going ashore there would have to make a direct assault against a small, defended island. To protect the flanks of the Marines landing on Tulagi, it was decided to first seize key points overlooking Tulagi on nearby Florida Island.

Japanese troops in the Solomon Islands in the summer of 1942 constituted a force to be reckoned with, but were not numerically superior, while the Japanese command structure was disjointed and plagued with a lack of cooperation between the Army and Navy. Army forces in the area centered on the Japanese 17th Army under the command of Lieutenant-General Harukichi Hyakutake, who was preoccupied with the conquest of New Guinea. The naval commander tasked with defense of the area was Vice-Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, a seasoned officer who had commanded the escort for Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s carrier force from Pearl Harbor to the Indian Ocean. Mikawa was in command of the 4th Fleet, which was not a large force and was composed of either middle-aged or older ships. Although Mikawa was tasked with defense of the area, he did not have control over the air units at Rabaul. They were controlled by Vice-Admiral Nishizo Tuskahara, Commander of the 11th Air Fleet. Mikawa was justifiably concerned with the command and control measures this caused and the general lack of preparedness.

For the Guadalcanal campaign the American command was set up under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz although Ghormley would be in overall command of the operation, codenamed Watchtower. Ghormley, in turn, would appoint Vice-Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher as commander of the entire task force. This naval task force, designated an Expeditionary Force, was made up of two groups: the aircraft carriers constituted the Air Support Force, under Rear-Admiral Leigh Noyes; while other warships and the transports were organized as the Amphibious Force, under Rear-Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner. Major-General Vandegrift would command the Marines as part of the Landing Force.

Vice-Admiral Gunichi Mikawa was the architect of the battle of Savo Island. This battle was the worst defeat suffered by the American Navy since Pearl Harbor. Mikawa was appalled by the lack of a cohesive Japanese command in the Solomon Islands area. (Naval Historical Center)

Guadalcanal would set the tone for the future campaigns of the war in the Pacific – not just one battle of quick duration, but a series of land, air, and sea battles “slugged out” along a narrow coastal belt, in restricted waterways and in the air space over Guadalcanal. The reason why the campaign was to be so prolonged was that neither side would be able to mass its forces at a critical juncture to obtain a decisive victory. The eventual outcome would be decided by the dogged determination of the American forces committed to the campaign and the release of critically needed supplies and equipment – coupled with luck.

Initially, the Japanese were successful in the early naval battles. With the battle of Savo Island (August 8–9) they achieved a great naval victory that severely crippled the US Navy’s ability to support the operations ashore and in the waters surrounding Guadalcanal. And, initially, with their land-based fighters they were also able to control the air space overhead. Their ground forces were seasoned fighters and had achieved notable military successes up to Guadalcanal.

Japanese soldiers were masters of jungle warfare but their tactics were poor and their tanks were inadequate. Communications in the jungle were also poor and tropical disease was a major problem – of the 21,500 casualties suffered by the Japanese in the campaign, 9,000 were to die of tropical diseases.

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) was fairly well organized at the regimental level and below, but rarely did it operate at a divisional level. It consistently underestimated the capabilities of its enemies, a course of action that would prove disastrous on Guadalcanal. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) on the other hand was an efficient organization. Tactically it could operate by day as well as by night. It was a disciplined aggressive force that carried out its assigned tasks without hesitation, using its weapons systems with deadly efficiency. The most serious failing of the IJN was its inability to exploit its successes. Time and time again throughout the naval campaign the Japanese achieved a tactical victory and then departed. By exploiting their successes they could have achieved a strategic victory. In the air, the Japanese had clearly achieved a technological masterpiece with the Zero fighter. This aircraft, with its lightweight construction and high-rate of climb, could outmaneuver any American plane on Guadalcanal, but its missions were restricted due to limited fuel supplies.

The American troops who invaded Guadalcanal were for the most part untried volunteers. The majority of the equipment that the Marines had was World War I vintage and unsuited for conditions on Guadalcanal. Communications were a problem, but since the Marines had mostly internal lines, these were not as severe as the problems experienced by the Japanese. The tactics used by the Marines to encounter the Japanese were basic. Preparing to seize and then defend the airfield, they held the key terrain features that were encompassed by the Lunga Perimeter. On these they created strong points, forcing the Japanese to attack at a disadvantage. The Marines also discovered that in the jungle flanking attacks on dug-in positions worked much better than frontal assaults.

American artillery was accurate and the Stuart light tanks brought ashore by the Marines were utilized effectively. They were light enough to be employed in the jungle clearings and superior to their Japanese counterparts. Later, when the Army was brought in to reinforce and eventually to relieve the Marines, they could benefit from the Marines’ experience and were better equipped.

The US Navy’s entry to the campaign did not start off on a good note. The battle of Savo Island was the worst naval disaster since Pearl Harbor. Most of the equipment on board the ships was World War I vintage and radar was not effectively exploited. But it soon learned from these early errors.

At the start of the battle, the Japanese had air superiority, as shown by this downed Wildcat on Guadalcanal. (Tom Laemlein)

During the battle for Guadalcanal, Marines used a variety of weapons, including two types of the Reising .45cal submachine gun, as well as the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). (USMC)

Damage control was a key aspect of the naval war; if a Japanese ship was damaged in a naval engagement it would have to be out of range of American aircraft from Guadalcanal by daylight – if not, it would be sunk by those planes. In contrast, damaged American ships could be repaired at a series of “local advanced naval bases” and be returned to fight again.

The Transport Division (TRANSDIV) was divided into two groups, X-RAY Guadalcanal and Y-OKE (Tulagi). The Marines of X-RAY, under Major-General Vandegrift, the Division Commander, were to land on Guadalcanal, while smaller, more specialized groups of Y-OKE were organized to assault Florida Island, Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo under the command of Brigadier-General William H. Rupertus, the assistant division commander. A total of 1,959 officers and 18,146 enlisted Marines and Navy Corpsmen comprised the amphibious landing force.

It was still dark (0400hrs) on August 7, 1942, when the amphibious task force silently separated into two groups as it approached Savo Island. Prior to their arrival in the area, the task force had conducted an amphibious rehearsal in a remote portion of the Fiji Islands. The rehearsal, conducted in high surf conditions on beaches obstructed by coral reefs, was a disaster and was aborted to avoid injury to the personnel and damage to the precious landing craft, which did not bode well. The American amphibious forces were embarked on 19 transports and four destroyer/transports. There were five cargo ships, eight cruisers, 14 destroyers, and five minesweepers. The accompanying carrier support group consisted of three battle groups, Saratoga, Enterprise, and Wasp. One battleship, North Carolina, and a force of cruisers and destroyers screened the battle groups. This force stayed to the south of Guadalcanal while the amphibious force sailed north, dividing in two when they approached Savo Island.

The movement to the amphibious objective area was shielded from the Japanese on Guadalcanal by one of the many tropical rainstorms that frequent the region. Once the two groups separated they proceeded to their assigned beaches. After arriving on station, naval gunfire and carrier aircraft began to bombard their respective targets in accordance with the landing plan. The pattern of future campaigns in the Pacific was about to be demonstrated.

The Marine planners felt that before Tulagi could be taken, certain key terrain features on nearby Florida Island would have to be captured. At 0740hrs on August 7, 1942, 20 minutes before H-Hour, the first amphibious landing operation in the Solomon Islands was undertaken to secure a promontory that overlooked Beach Blue – the Tulagi invasion beach. A second unopposed landing was also made at Halavo to secure the eastern flank of the Gavutu landings.

Tulagi was attacked at 0800hrs, according to schedule. The first to see action were the Marines of the 1st Raider Battalion, commanded by Colonel Merrit A. Edson, and they were followed by the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines. The assault waves made their way onto the beach through water ranging from waist to armpit level. Upon reaching the shore, the Raiders moved east and the 2nd Battalion moved northwest. Japanese resistance was encountered almost immediately but was systematically overcome. The advance continued slowly until dusk, when they consolidated and dug in for the night. This first night on Tulagi was to be indicative of many future nights in the Pacific: four separate attacks were launched by the Japanese to dislodge the Raiders from their positions; each attack was beaten back. Despite some further pockets of resistance, by nightfall on August 8, 1942, Tulagi was in Marine hands.

These two small islets, connected by a causeway, were to be seized by two companies of the 1st Parachute Battalion. Gavutu, the higher in elevation of the two islands, was to be taken first. The amphibious assault was to take place at H-Hour + 4 (1200hrs) on August 7. The plan called for a landing on the northeast coast. The naval gunfire support for the Gavutu amphibious assault was so effective, however, that it actually began to work against the attackers: so complete was the destruction that the original landing site, a concrete seaplane ramp, was reduced to rubble. The landing craft were forced to divert farther north to land the Parachutists and in so doing were exposed to flanking fire from Tanambogo. Despite heavy casualties, the Parachutists took the northeastern portion of the island. However, a small detachment of Marine reinforcements, deployed during a night-time assault, was badly mauled.

On August 8, the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, was ordered to reinforce the Parachutists on Gavutu and then attack Tanambogo. Supported by tanks from the 2nd Tank Battalion and with air and naval gunfire support, an amphibious landing was made at 1620hrs on August 8, 1942, on Tanambogo. Once a beachhead was established, reinforcements crossed the causeway, and by 2300hrs, two-thirds of the island was secured. After a lot of fighting during the night, the island was completely secured by late on the 9th. Once Tanambogo fell, organized resistance in the Tulagi, Gavutu, Tanambogo, and Florida Islands ceased. In all, the operation had taken three days. American losses overall were light, and the Japanese lost 1,500 troops. Only a handful of prisoners were taken.

A US Marine LVT shown landing at Guadalcanal. (Tom Laemlein)

On Guadalcanal an unopposed landing was made at Beach Red, about 6,000 yards east of Lunga Point. It was spearheaded by the 5th Marines, followed by the 1st Marines, and by 0930hrs the assault forces were ashore and moving inland. Their plan was simple: the 5th Marines would proceed along the coast, securing that flank, while the 1st Marines would move inland through the jungle and secure Mount Austen, described as a grassy knoll and reportedly only a short distance away. Now came the realization that intelligence concerning the terrain on Guadalcanal was faulty. Mount Austen was both four miles away and the most prominent terrain feature in the area – it would not be captured until months later. The remainder of the first day was spent consolidating positions and attempting to disperse the supplies that were stockpiling on the beach. Meanwhile the strongest Japanese countermeasure came at 1400hrs in the form of an air raid by 18 twin-engined Type 97 bombers, two of which were shot down. A second wave of Type 99 Aichi bombers that came later was also repulsed with the loss of two aircraft.

At 2200hrs, General Vandegrift issued the attack order for the next day. With Mount Austen out of reach and only 10,000 Marines ashore, he ordered the airfield to be taken and a defensive perimeter set up. August 8, therefore, began with a westward advance by all Marine forces on Guadalcanal. The airfield remained the primary objective. Contact with small groups of Japanese began to occur as the Marines closed on the airfield. In the Lunga region, just south of the airfield, defensive positions consisting of trenches and antiaircraft emplacements, well built and equipped, were discovered deserted. The airfield, nearly 3,600ft long and in its last stages of construction, was defended by a small group of Japanese who were overcome. By the end of the day, the airfield had been taken and a defensive perimeter established. It was later revealed that the Japanese had been aware of the impending American assault but had thought it was only to be a raid. Therefore Japanese troops in the area had been instructed to withdraw into the hills until the Americans departed. So far the Japanese resistance had been less than effective. In the air, attacks were repulsed with minimum damage to the Americans. However, the Japanese had no intention of giving up the Solomon Islands without a fight.

Early on August 8, part of the Japanese 8th Fleet under Admiral Mikawa made preparations to attack the American amphibious task force. Mikawa’s battle group consisted of five heavy cruisers and two light cruisers plus a destroyer. With this formidable force he began to move south. En route, he was spotted by an Allied patrol plane and there began a tragic chain of events that would lead to one of the greatest naval disasters ever suffered by the American Navy.

After the assault troops had moved inland, Beach Red became somewhat chaotic. Not enough manpower was allocated to move the masses of supplies from the landing craft to the beach, and there was not enough motor transport to move supplies from the beach to the dumps. By the end of the first day the unloading of supplies had to be suspended, as there was no place on the beach to put them. The congestion depicted here is indicative of the problems experienced. (USMC)

Although there was considerable confusion about which direction the Japanese force was heading in, Rear-Admiral Turner positioned two destroyers, Blue and Ralph Talbot, northwest of Savo Island, to maintain a radar watch on the channel. He then positioned three cruisers, the Australia, Canberra, and Chicago, along with two destroyers, the Bagley and Patterson, to patrol between Savo Island and Cape Esperance. Three additional cruisers, Vincennes, Astoria, and Quincy, along with two destroyers, Helm and Jarvis, were to patrol between Savo Island and Florida Island. Two other cruisers and two destroyers guarded the transports. As these events were occurring, Admiral Fletcher, in command of the carrier support group, felt that operational losses to his aircraft and dwindling fuel oil for his ships limited his effectiveness. He requested and was granted permission to withdraw on August 9. Once Rear-Admiral Turner was aware of Fletcher’s plans he also decided to withdraw his amphibious fleet which was vulnerable without air cover. This was despite the fact that the transports had not yet unloaded all supplies to the Marine force now on Guadalcanal.

But at 0145hrs on August 9, the Japanese naval force miraculously slipped past the radar picket destroyers. Launching a surprise nighttime attack the Japanese scored a major victory. The Allies (both US and Australian ships were present) lost four cruisers, with one cruiser and one destroyer damaged. Fortunately, Admiral Mikawa did not attack the transport area. Had he done so he could have effectively curtailed American operations in the area. Instead he broke contact and headed back to Rabaul to be out of range of American carrier aircraft. Meanwhile, the damage inflicted by the Japanese on the amphibious task force delayed its departure on August 9. But by 1500hrs, the first group of ships had departed; the last group left at 1830hrs.

One of General Vandegrift’s primary concerns was the threat of a Japanese seaborne invasion, so the bulk of the division’s assets were set up to repel a counterlanding. Seen here are two Marines manning a M1917 (top) while a M3A1 light tank is dug in and camouflaged as part of a beach defensive position (bottom). (Tom Laemlein and USMC)

THE FIRST WEEK

With the withdrawal of the amphibious task force the Marines were left without air support. The withdrawal of the transports had left the Marines with only part of their supplies: ammunition was adequate, but food was a much more serious issue and by August 12 the division was on two meals a day. The captured airfield, renamed Henderson Field, would now have to be developed for the mission to be a success. Until it was completed, the Marines would be at the mercy of any Japanese air or naval attacks. By August 20, the Marines would have aircraft based on the island. Initially just 19 Wildcats and 12 dive-bombers were available but they were eventually supplemented by some Army Air Corps’ P-400s.

Two American Marines firing a captured .50cal Japanese machine gun at Japanese planes during the battle for Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. (Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis)

“Before Guadalcanal the enemy advanced at his pleasure – after Guadalcanal he retreated at ours.”

— ADMIRAL “BULL” HALSEY

In the first week the tone of the campaign was set. Daily – and this was to continue for months except when weather and American fighter aircraft were present – Japanese planes made incessant air raids. The targets were either Henderson Field or resupply shipping at Lunga Point. At night the perimeter was bombarded by Japanese warships. All in all, the situation looked pretty bleak for the Marines, virtually abandoned by the Navy. Having quickly established themselves ashore, they began to improve the perimeter. Considering a Japanese invasion more than likely, General Vandegrift concentrated the bulk of his combat units along the beach. Once the Lunga Perimeter was established, patrols were sent out to gain information on the Japanese forces on the island. So far as could be determined, the bulk of the Japanese forces were concentrated west of the perimeter, in the Matanikau River and Point Cruz area and a number of operations were launched to clear the defenders.

Colonel Kiyono Ichiki was the leader of the 900-man Japanese force that attacked the Marines at “Alligator Creek.” Contrary to popular belief, he did not commit suicide after burning his regimental colours after the aborted attack: last seen he was rallying his men as they attacked the Marines. More than likely he was killed attempting to cross the sand spit. (USMC)

On August 19, a battalion-sized operation by the 5th Marines was launched against the Japanese in the Matanikau area, its mission being to drive the Japanese out of the region. Company B, 1st Battalion, was to approach using the coastal road and fight a spoiling action at the river mouth, while a second company (Company L, 3rd Battalion) was to move overland through the jungle and deliver the main attack from the south. The third company (Company I, 3rd Battalion) would make a seaborne landing to the west near Kokumbona village and cut off any retreating Japanese. The operation was a success and the Marines succeeded in destroying the small Japanese garrison in the area.

On August 13, the Japanese High Command ordered Lieutenant-General Haruyoshi Hyakutake’s 17th Army at Rabaul to retake Guadalcanal. The naval commander for this operation was to be Rear-Admiral Raizo Tanaka. With no clear intelligence picture of the American forces on Guadalcanal, Hyakutake decided to retake it with 6,000 troops from the 7th Division’s 28th Infantry Regiment and the Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force. The spearpoint of the effort would be made by the reinforced 2nd Battalion of the 28th Infantry Regiment, led by Colonel Kiyono Ichiki. Ichiki and an advance element of 900 troops were taken to Guadalcanal and landed at Taivu Point on the night of August 18, 1942. At the same time 500 troops of the Yokosuka 5th Special Landing Force went ashore to the west at Kokumbona.

These landings were the first run of what would be nicknamed the “Tokyo Express” by the Marines. This was basically a shuttle run organized by Admiral Tanaka. Composed of cruisers, destroyers, and transports, it shuttled troops and supplies at night from Rabaul to Guadalcanal. The route they took down the Solomons chain was nicknamed the “Slot.” After landing at Taivu, Colonel Ichiki established his headquarters, sent out scouting parties, and awaited the arrival of the remainder of his regiment. Once he had the rest of his troops and accurate intelligence on the Americans he would attack. The intelligence picture Ichiki had was that a raiding party of Americans was cowering in a defensive perimeter around the airfield. Ichiki’s plan was to march to the former Japanese construction camp east of the Tenaru, establish it as his headquarters and then move against the Americans. But his scouting party was destroyed by a US Marine patrol. Fearing he had lost the element of surprise he decided to march westward with the troops he had to hand.

On the night of August 20/21, Marine listening posts detected the movement of a large body of Japanese troops. The listening posts had no sooner withdrawn than a severely wounded native, Jacob Vouza, a sergeant in the native police contingent, who had been tortured and left for dead by the Japanese, stumbled into the Marine lines and, before collapsing, imparted the news that the Japanese were going to attack. No sooner had Vouza arrived than the first Japanese, who were marching in formation, ran into a single strand of barbed wire placed across the sand bar at the mouth of the creek. This temporarily disorganized the leading elements of Ichiki's force, who were not expecting to run into any defensive positions so far east.

The ensuing battle that erupted, which would later be referred to as the battle of the Tenaru, was fierce and savage. Using human wave tactics, the Japanese attempted to crush Lieutenant-Colonel Edwin A. Pollock’s 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, which was defending the area.

The aftermath of the battle of the Tenaru clearly indicates the determination of the Japanese attackers. The dead Japanese in the foreground had actually penetrated to the west bank of the creek before they were stopped by the defending Marines. The Marines in the background are walking through the area to survey the aftermath of the battle. (NARA)

Unable to dislodge the Marines, Ichiki sent part of his force south along the east bank to cross the creek upstream in an attempt to outflank the Marines. This attempt failed. He then sent a company out through the surf in an attempt to break through from the north. This attempt also failed and Ichiki was killed. But the fight continued throughout the night. In the morning the Marines were still holding. It was then decided to conduct a double envelopment to eliminate Ichiki’s force. Supported by light tanks, artillery, and newly arrived fighter planes, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, which had been held as division reserve, outflanked Ichiki’s force and destroyed it. Of the original 900 Japanese troops, 800 were dead or dying on the sand bar and in the surrounding jungle. The cost to the Marines was light: 34 killed and 75 wounded.

While the issue on land was being decided the Japanese assembled a major naval task force under admirals Tanaka and Mikawa. At the same time an American naval task force under Admiral Fletcher which was operating southeast of the lower Solomons in what it believed to be a safe area, became engaged in the battle of the Eastern Solomons. Unaware of what had happened to Ichiki, the Japanese had planned on reinforcing him with a larger secondary force of about 1,500 troops. This force departed on August 19 in four transports screened by four destroyers. They were to land on Guadalcanal on August 24. To support the transports and operations ashore the Japanese dispatched two naval task forces composed of five aircraft carriers, four battleships, 16 cruisers, and 30 destroyers.

Three American carrier groups, comprising three aircraft carriers, one battleship, six cruisers, and 18 destroyers, were operating about 100 miles southeast of Guadalcanal. Somehow, an erroneous intelligence report on August 23 indicated that the large Japanese force, believed to be in the area, was returning to the Japanese base at Truk Island. Operating on this mistaken belief, one of the carrier groups based around Wasp departed from the group to refuel. This left two carrier groups formed around Enterprise and Saratoga.

Shortly afterward, patrol planes discovered the Japanese transport group 350 miles from Guadalcanal. The next day, August 24, American carrier planes discovered the Japanese forces, and at the same time Japanese carrier planes discovered the American forces. In the ensuing air-to-ship, air-to-air battle, the smaller American force turned back a larger Japanese force. The Japanese were able to land 1,500 troops and bombard Henderson Field; but they were not able to intervene in the ground fighting. Also, they were no longer able to control the air space over Guadalcanal. The Japanese lost the carrier Ryujo, one destroyer, one light cruiser, and 90 aircraft, with one seaplane carrier and a destroyer damaged. Shortly after the battle the American naval force departed. The Americans had sustained damage to one aircraft carrier, Enterprise, and had lost 20 planes. Far more serious losses followed. On August 31, the aircraft carrier Saratoga, patrolling west of the Santa Cruz Islands, was torpedoed. The aircraft carrier Wasp, on patrol southeast of the Solomons, was torpedoed and sunk on September 15. With one carrier sunk and two damaged, Hornet was the only remaining American aircraft carrier in the South Pacific. Meanwhile on Guadalcanal itself a second so-called “battle of Matanik” was fought with an attempt to place the 1st Battalion 5th Marines ashore west of Point Cruz but again no decisive results were achieved. The Japanese defenders eventually chose to retire and the Marines returned to the Lunga Perimeter.

While the ground fighting was going on, important strategic developments were taking place. A Marine air wing was beginning to establish itself at Henderson Field. On September 3, 1942, the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, under Brigadier-General Roy S. Geiger, arrived. With the arrival of the wing, the tide in the air would eventually be turned against the Japanese pilots.

In early September, the islanders reported that several thousand Japanese had occupied and fortified the village of Tasimboko, about eight miles east of Lunga Point. These reports were dismissed by Marine intelligence, but as a precautionary measure it was decided that an amphibious raid should be made against what was believed to be a small Japanese garrison force. Marines were drawn from the 1st Raider Battalion and the 1st Parachute Battalion under the command of Colonel Merritt A. Edson.

US Wildcats pictured on the captured Guadalcanal airfield, which was quickly renamed Henderson Field by the Marines. (Tom Laemlein)

The Raiders landed at dawn September 8, followed shortly afterward by the Parachutists. As they moved west they met minimal resistance until they approached Tasimboko, when resistance dramatically increased. The Japanese troops, estimated at 1,000, were well armed and equipped. They were also supported by field artillery firing at point-blank range but the Marine force succeeded in occupying the village. There they discovered thousands of life jackets and multiple supplies. What they did not know was that the Japanese they had just fought were the rear party of the 35th Infantry Regiment (or Kawaguchi Brigade, as it was referred to). Totaling more than 3,000 troops commanded by Major-General Kiyotaki Kawaguchi, it had arrived between August 29 and September 1.

Two events saved the smaller Marine force from being destroyed by the numerically superior Japanese. First was the fact that Kawaguchi had begun to move southwest through the jungle. His intention was to move undetected to the south of Henderson Field and then launch an attack north from the jungle. Second, an American resupply convoy en route to Lunga Point was passing by the area. The Japanese incorrectly concluded that the convoy was reinforcing the Marine attacking force and a full-scale landing was being made. Kawaguchi and Edson would meet again, less than a week later, on a grassy ridge overlooking Henderson Field.

After Tasimboko it was decided to put the Raiders and Parachutists in a reserve position. They were to occupy a defensive position on a series of grassy ridges south of Henderson Field, near the division command post. But patrols and native scouts began to encounter increasing Japanese opposition. On September 10, native scouts reported that the Japanese were cutting a trail and were five miles from the perimeter. A major Japanese offensive was in the making. The ridge positions were also bombed in daily air raids. Unable to advance, the Marines consolidated their positions on the southernmost knoll of the ridge complex. This would be the start of a crucial battle that would be called the battle of “Bloody Ridge” – a turning point in the campaign.

To defend the area, Edson positioned his composite battalion of Raiders and Parachutists in a linear defense along the southernmost ridge and in the surrounding jungle. The western flank was anchored on the Lunga River. The attack began that evening with shelling from Japanese warships, followed by repeated probings of the Marine lines from the jungle to the south. Later that night the Kawaguchi Brigade repeatedly struck. Preceded by a 20-minute naval bombardment, powerful thrusts were directed from the west primarily against the companies that occupied the jungle terrain flanking the ridge. The Raiders were pushed back and the next day, September 13, Edson attempted to use his reserve companies to dislodge the Japanese who had established a western salient into his position. This daylight attack did not meet with success, so the Marines began to prepare for the inevitable night attack. Throughout the day Japanese planes attacked the Lunga Perimeter, sometimes bombing the ridge. The second night, Kawaguchi struck with two infantry battalions. He succeeded in driving the Marines back to the northernmost knoll of the ridge. But from this final position the Marines held back the Japanese onslaught. Kawaguchi knew that he would have to overwhelm the enemy if his attack on Henderson Field were to succeed; Edson knew that at this stage of the battle his troops were no longer just fighting to save Henderson Field – they were fighting to save their very lives.

At dawn on September 14, planes from Henderson Field and the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, supported the Raiders and Parachutists in driving the remainder of Kawaguchi’s forces back into the jungle. Kawaguchi had been defeated; the majority of his troops were either dead or dying. The Marines lost 31 killed, 103 wounded, and nine missing; the Japanese lost more than 600 killed. For his heroic defense of “Bloody Ridge” Henderson Field, Edson would receive the Congressional Medal of Honor. While Kawaguchi was attacking the ridge, two other companies attacked the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, at “Alligator Creek” but this too was repulsed.

With all the Japanese attacks repulsed, Vandegrift decided to expand the Marine perimeter. Bolstered by the addition of the 7th Marines, recently transported from Samoa, Vandegrift tasked them with clearing the Japanese from the Matanikau area. The action was initially planned to be accomplished in two separate phases. A reconnaissance in force by the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, was to be conducted from September 23–26 in the area between Mount Austen and Kokumbona. On September 27, the 1st Raiders Battalion was to conduct an attack at the mouth of the Matanikau River with the objective of pushing through to Kokumbona and establishing a patrol base there. The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel “Chesty” Puller, set out as scheduled. Late in the evening of September 24 the battalion made contact with a strong Japanese force near Mount Austen.

This is the road that leads from “Bloody Ridge”' to the airport. In this picture it is very easy to see why the defense of Bloody Ridge was so critical. Once the Japanese advanced to the open plain in the foreground, they would have seized the airfield and driven a deadly wedge between the Marine forces. Had the Japanese succeeded, there is some doubt whether they could have been ejected. (USMC)

General Vandegrift, fearing that Puller had made contact with a strong Japanese force, sent the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, to reinforce him. The combined force then continued its advance to clear the east bank of the Matanikau. As it approached the river mouth on September 26, the combined force came under fire. The 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, succeeded in making its way to the mouth of the river, but could not force a crossing. It was decided to have Puller’s Marines and the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, hold and engage the Japanese at the mouth of the river.

The 1st Raider Battalion, meanwhile, had set out from the perimeter. However, developments at Matanikau River resulted in the Raiders moving eastward and planning to strike the Japanese from the rear. The action began early on September 27 with the Raiders, now under Lieutenant-Colonel Sam Griffith (Edson having been promoted and given command of the 5th Marines), moving up to their intended crossing point. But concentrated enemy fire succeeded in stopping the assault and preventing the Raiders from deploying. From this point on, the American operation degenerated.

A message from the Raiders was interpreted incorrectly at division headquarters, and believing that the Raiders had successfully crossed the river, two companies from Puller’s battalion were sent to assist in a shore-to-shore landing west of Point Cruz. The landing was unopposed but mortar bombs fell on the Marines just as they reached the ridges 500 yards south of the landing beach killing the commanding officer. A strong enemy column from Matanikau River then engaged the Marines. Now all three Marine forces were in combat with the Japanese but unable to support each other. The force west of Point Cruz realized they were in danger of being surrounded so since they had no radio equipment spelt out “HELP” using their T-shirts. This was spotted by a dive-bomber pilot who radioed a message to the 5th Marines. Puller subsequently left the Matanikau area to rescue his isolated companies. Using a small flotilla of landing craft the companies were finally evacuated at a cost of 24 killed and 23 wounded. The Japanese force was estimated to have been 1,800 strong with 60 killed and 100 wounded. Once the withdrawal was accomplished, the Marines along the Matanikau also pulled back to the perimeter, leaving the Japanese still in control of the region and ending the ground fighting for the month of September. Meanwhile the naval actions during the month had been limited to the nightly attempts to interdict the “Tokyo Express.”

In October the Americans intended to drive the Japanese from their Matanikau stronghold, and intelligence reports indicated that the Japanese were massing in the region for another all-out attack. General Vandegrift planned for the 5th Marines (minus one battalion) to conduct a spoiling attack at the mouth of the Matanikau River, which would focus Japanese attention on that area; while the 7th Marines (minus one battalion), reinforced by the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, would cross the river upstream, then turn north to clear the area on the west bank. The operation would be supported by artillery and from the air with the objective to prevent Japanese artillery from firing at Henderson Field.

Meanwhile the Japanese hoped to seize positions east of the Matanikau River to establish better positions for their artillery. Fortunately for the Marines, they put their plan into action first. The plan called for the 5th Marines to set up positions on the east bank of the Matanikau running south from the mouth by 1,800 yards. The main force, composed of the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, and the 7th Marines would cross the Matanikau, moving northward, and then assault the Matanikau village. On October 7 the advance began. By noon, the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, had made contact with a Japanese company which they began to drive back. At 1830hrs on October 8 the Japanese attacked in force but were ultimately unsuccessful. On October 9 the main attack was launched. The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, came across a large concentration of Japanese from the 4th Infantry Regiment camped in a deep ravine. Using artillery and mortars the Marines decimated the Japanese and more than 700 were killed.

The Japanese, who had been planning a full scale counteroffensive since August, had completed new preparations by October. The planned Army–Navy operation for the recapture of Guadalcanal was to be directed by General Hyakutake, commander of 17th Army.

This major counteroffensive was to be launched on three fronts. The first phase began at sea, with the battle of Cape Esperance. In this battle the opposing naval forces made contact near Savo Island. The Americans under Rear-Admiral Norman Scott took up a north–south position against the Japanese force that was moving at a right-angle toward it. Admiral Scott then executed a classic crossing the “T” maneuver, the main batteries of the American ships being brought to bear on the Japanese ships traveling in a lineahead formation. As a result the Japanese were forced to retire. On each side a destroyer was lost and a cruiser damaged. It was not a major victory, but the naval balance of power was starting to shift toward the Americans.

On October 13, the Japanese struck Henderson Field with an intense aerial bombardment. Artillery fire followed and shortly before midnight two Japanese battleships began a systematic bombardment. When they retired, bombers hit the airfield again. By the afternoon of October 14, Henderson Field was completely out of action. Only minimal operations could be carried out from a nearby grass runway. On October 15, five Japanese transports began to unload troops and supplies at Tassafaronga Point, and despite coming under US Navy fire managed to offload 3–4,000 troops and 80 percent of their cargo.

The terrain the Marines moved through in the Matanikau region was hardly passable. Often the point elements had to blaze a trail through tangled terrain, and progress was extremely limited. In this picture, a machine gun crew struggles to get its ammunition cart up a slight slope. Working like this in the heat and humidity sapped the endurance of the Marines. (USMC)

With the arrival of the last of his troops, General Hyakutake was confident of success. The plan of attack was to be four-pronged. Lieutenant-General Masao Maruyama was to lead the main force and attack from the south, near “Bloody Ridge.” The second prong, under Major-General Tadashi Sumiyoshi, was to attack from the west with tank support and cross the Matanikau River. The third prong was to cross the Matanikau River a mile upstream and move north against the Marines while the fourth prong called for an amphibious assault at Koli Point. In the event this was canceled when the Japanese believed American resistance was about to collapse. The attack was to commence on October 22; however, movement through the jungle caused unexpected delays – delays that upset a very elaborately coordinated attack schedule. All supplies had to be man-packed, and the artillery pieces were the first to be left along the tortuous trail that made its way up and down the steep slopes south of Mount Austen. As a result, Maruyama was forced to delay his attack until the 24th.

Meanwhile Major-General Sumiyoshi, who was out of communication with Maruyama, began his attack on the afternoon of October 21 but was driven back. The following day was quiet until 1800hrs. But this time the Marines were ready. Artillery and a concentration of anti-tank weaponry waited for the Japanese. The massed Marine artillery fire virtually annihilated Sumiyoshi’s troops and the Marines still held the western sector. The following night, October 24, during a rainstorm, Maruyama’s forces launched their attack against the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Puller.

The Japanese had finally hacked their way through the jungle and were just south of “Bloody Ridge” but were now only armed with machine guns – all the artillery and mortars had been abandoned in the jungle. Simultaneous with Maruyama’s attack was the third prong attack on the southwestern side of the Marine perimeter. Puller’s Marines were supplemented by the 7th Marines reserve force. The Japanese resolutely attacked during the night, but every charge was beaten back. The following day, October 25, became known as “Dugout Sunday” as the Japanese continuously shelled and bombed Henderson Field. That night Maruyama attacked with his 16th and 29th Infantry Regiments along the southern portion of “Bloody Ridge.” Again the Marines and soldiers, supported by Marine 37mm anti-tank weapons firing canister rounds, repulsed the final assault. At dawn Maruyama withdrew, leaving more than 1,500 of his troops dead in front of the Marine lines. That same night the third prong forces also met with defeat when attacking the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines, to the east of the Matanikau River. These unsuccessful Japanese attacks marked the end of their October counteroffensive. It would also be the high water mark for the Japanese in the campaign. Other battles, many just as fierce, were yet to be fought, but October would be the decisive month on land.

At sea, October ended with the battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. In that battle, a strong Japanese force that had been maneuvering in the area was attacked by a naval task force under Rear-Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid. In the ensuing battle the Americans lost an aircraft carrier and a destroyer, while another aircraft carrier, a battleship, a cruiser, and a destroyer were damaged. The Japanese lost no ships while sustaining damage to three aircraft carriers and two destroyers; but their forces departed the area.

November was a month of change in the campaign. The South Pacific Area received a new commander: Admiral Ghormley was relieved and Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey took command. With Halsey came the much-needed troops and supplies to maintain the American presence in the area.

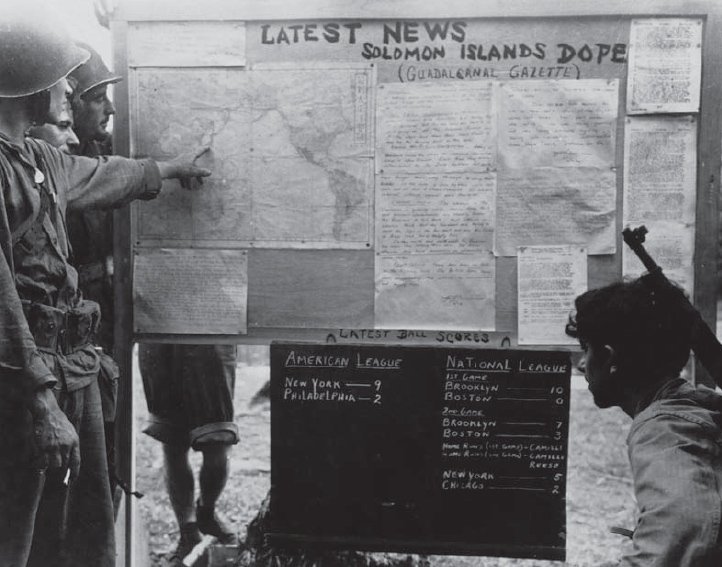

US Marines at the Guadalcanal battle front keep up with the news at home and check their position on the map at a news board, known as the Guadalcanal Gazette, set up for their benefit. Even in the midst of a long campaign, the sports results were of upmost importance. (Bettmann/Corbis)

As the 2nd Marine Division began to pursue the retreating Japanese along the coast, they erected bridges by “field expedient” means. These Marines are crossing the Bonegi River on crude log bridges. (USMC)

The month was characterized by heavy naval actions. The Japanese organized four naval task forces for their November operations. Two bombardment forces were to shell Henderson Field; a third was to transport the 38th Division and its equipment to Guadalcanal; a fourth would be in general support. The American naval forces under Halsey’s command were organized into two task forces. One was led by Rear-Admiral Turner and the other by Admiral Kinkaid. These forces, although limited, had the task of reinforcing and resupplying Guadalcanal as well as stopping the Japanese from taking it over.

Kinkaid’s battleships would protect Turner’s amphibious craft and warships. Turner’s force was subdivided into three groups – the first carrying reinforcements and commanded by Admiral Scott; the second, commanded by Admiral Callaghan, would provide the screen while the third group, commanded by Turner, would be transports carrying vital supplies. All the groups arrived on November 12. At 1035hrs a large Japanese naval force was spotted sailing toward Guadalcanal. The Japanese force consisted of the battleships Hiei and Kirishima, one light cruiser, and 14 destroyers. Their orders were to neutralize the airfields on Guadalcanal.

In what would be called the First Battle for Guadalcanal, Callaghan led his outmatched cruiser force against the Japanese battleship. The main action began at night near Savo Island. The vanguards of the opposing forces intermingled and the American column penetrated the Japanese formation. The outnumbered Americans returned fire from all directions and the engagement degenerated into individual ship-to-ship actions. When the battle was over, admirals Callaghan and Scott were dead, but the Japanese had been turned back. Not one Japanese shell had struck Guadalcanal although of the 13 US ships involved 12 had been sunk or damaged.

On land the situation was also improving. The 5th Marines spearheaded a western attack that cleared the Japanese out of the Matanikau area. The US advance continued until just short of Kokumbona. On the opposite side of the perimeter, the 7th Marines and the remainder of the 164th Infantry made an eastern push that drove the Japanese from the Koli Point area despite bitter resistance. On November 4, both battalions began an eastward advance under the cover of artillery and naval gunfire. Their action was reinforced by the Army’s 164th Infantry. By November 9, the combined American forces had located the Japanese once again and began to surround them. Over the next few days all Japanese attempts to break out were foiled, and the Marines and soldiers, supported by artillery, began to reduce the pocket of resistance. By November 12, they had completed their mission. In this final eastern action, the Americans had lost 40 killed and 120 wounded; the Japanese had lost more than 450 killed.

“Most of the men are stricken with dysentery… Starvation is taking many lives and it is weakening our already extended lines. We are doomed.”

- MAJOR-GENERAL KENSAKU ODA, JANUARY 12, 1943

First aerial view of the much contested Guadalcanal Airport built by the Japanese. This photograph was taken by an official Navy photographer shortly after the Japanese were driven out by US Marines. It shows the almost finished runaway which the Americans were able to complete, ultimately giving them the aerial advantage over the Japanese. (Topfoto)

The Japanese attempted another reinforcing naval operation in the Second Naval Battle for Guadalcanal, but after a sharp engagement the Japanese were again turned back. The last naval action in November was the battle of Tassafaronga as a Japanese “Tokyo Express” destroyer force attempted to resupply the beleaguered Japanese troops. But this was intercepted by Rear-Admiral Carleton H. Wright. Each side lost a destroyer but again the Japanese were turned back. With the close of November, the Japanese no longer had control of the waters around Guadalcanal.

December saw some definitive changes in the campaign. The Lunga Perimeter was not much larger than it had been in the early days, but there were now enough troops to take decisive offensive action. The American Army was ashore in force, and was led by Major-General Alexander Patch, who had the Americal Division under his command. With Admiral Halsey in overall command, the bleak days were ending. Troops and equipment were pouring into Guadalcanal, and some of the worst-hit Marine units had been relieved and given a much needed rest. Meanwhile the new Army P-38 fighter aircraft was making its debut in the area, and B-17 bombers were now based at Henderson Field. With the tide of war turning it was decided to relieve General Vandegrift’s 1st Marine Division. On December 9, after more than four months of protracted combat, the Marines were pulled out. Sick, tired, dirty, and exhausted, they were glad to leave their island purgatory. Command of the ground forces was now turned over to Major-General Patch of the Army, who was left with an experienced cadre of troops, for he still had a major portion of the 2nd Marine Division in his command. Intelligence reports indicated that 25,000 Japanese were still on the island – in comparison with 40,000 Americans. However, the exact disposition of the Japanese forces was not known, although it was generally assumed that they were in the Mount Austen and Kokumbona area, and were still being resupplied by the “Tokyo Express.”

Mount Austen is not a single hill mass, but a spur of Guadalcanal’s main mountain range with a 1,514ft summit covered in dense rain forest. For the American soldiers who would have to fight there, Mount Austen was a jungle nightmare. Supplies had to be man-packed up the steep slopes and casualties evacuated back the same way. The fighting was fierce, and the Japanese were well dug in. The attack, which began on December 17, 1942, was not over until January 1943. American soldiers of the 132nd Infantry bore the brunt of the fighting, until hard hit by fatigue and illness during 22 days of intense jungle warfare, they were relieved on January 4. They had lost 112 killed in contrast to Japanese losses in the region of 450.

With the start of the New Year, Major-General Patch, now commanding XIV Corps, (Americal Division, 25th Infantry Division, 43rd Infantry Division, and 2nd Marine Division), resolved to bring matters to a close and drive the Japanese from Guadalcanal: in a series of quick offensive actions, he decided to drive westward and crush Japanese resistance between Point Cruz and Kokumbona. In a one-week period the Marines advanced more than 1,500 yards to a position from which a Kokumbona offensive could be launched. In the process they killed an estimated 650 Japanese. While these gains were being made, the 35th Infantry was engaged in heavy fighting at the Gifu, on Mount Austen, and in the hilly jungle area to the southwest centering on a feature known as the “Seahorse,” from its resemblance in an aerial photograph. In a difficult one-day battle the 3rd Battalion, 35th Infantry, seized the “Seahorse,” effectively encircling the Gifu. But it would take an arduous two-week battle to seize the Gifu itself with advancements made in 100-yard increments. In a hellish battle in the jungle, a lone US tank supported by 16 infantrymen penetrated to the heart of the Gifu and then began a systematic destruction of pillboxes and Japanese soldiers. By the night of January 22/23, the Gifu was quiet. The reduction of the Gifu had cost the Americans 64 killed and 42 wounded; the Japanese had lost more than 500 killed. Meanwhile, in a final two-day offensive that ended on January 24, 1943, Kokumbona was captured. At the end of January, the final task facing XIV Corps was that of pursuing and destroying the Japanese before they could dig in or escape.

By early February, Major-General Patch was convinced that the Japanese were planning a withdrawal, something he wanted to prevent. The American forces instituted a final pincer movement to trap the remaining Japanese troops. However, the US advance was too slow, and in the face of a determined Japanese delaying action 13,000 Japanese troops of the 17th Army were able to withdraw to Cape Esperance. The Japanese had been skillful and cunning. Nevertheless the essential significance of the campaign was unchanged. The first phase of the Solomons campaign was concluded as a victory for the Americans, and the first major step had been taken in the reduction of Rabaul.

Guadalcanal provided an archetype for jungle and naval warfare in the Pacific. It was a hard fought campaign that shattered the myth of Japanese invincibility. From the campaign a seasoned fighting force was created. Most important, the campaign validated the theories and practice of amphibious warfare that had been taught at the Marine Corps schools at Quantico, Virginia, in the late 1920s and 1930s. The important gain for the Americans was Guadalcanal itself. It would be developed into one of the largest advanced naval and air bases in the region and would be a springboard for future amphibious operations in the region. And by holding it the Americans had kept open the lines of communication with Australia.

The cost of the campaign had not been prohibitive for the Americans. Total Army and Marine losses were 1,600 killed and 4,700 wounded. The Japanese lost considerably more: 25,400 from all services. Naval losses were more even with each side losing about 25 major warships.