6

Leveraging Momentum and Context

The format we have chosen to deliver this section's topic is fraught with irony. We are going to teach you about immediacy in one of the least immediate formats currently available: a book. To compensate, we will offer some format experiments to promote active learning as you read. A good teacher might refer to using devices such as note‐taking templates or mind maps. Their goal in using such instruments is to make thinking visible. Having thought through where our lesson could go wrong for our learners, our goal is similar: to help you see and surface your thinking at the times when such a practice will, hopefully, be most valuable to you. With all of that off our chests, this somewhat winding road of a paragraph leads to our opening analogy.

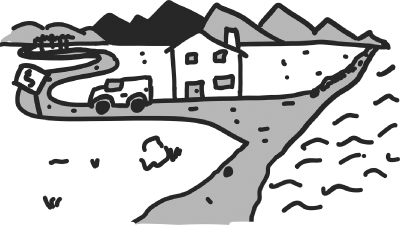

There's a road on Bainbridge Island near Seattle, Washington, that is one of the most dangerous and exciting roads that we have ever seen. It essentially winds down toward the water and has room for one car, or to be more precise, about 96% of one car. As you are driving down it, you feel as though part of your car is hanging off the cliff. You are descending through steep curves, and it is beautiful when you catch a glimpse of the water, but…at some point, you realize that there are no one‐way signs and that the narrow road is actually a regular, two‐way road. Cars go down toward the houses at the bottom, and cars go up toward the bustle of commerce and entertainment or the ferry to Seattle, a center of even more commerce and entertainment.

Strict local laws govern the road. If you are driving to the homes below, bringing groceries, services, or good cheer, you must yield to those heading up the road. Yielding does not just mean stopping or pulling off, since there is nowhere to park your car. You have to drive backward up the hill, using your rearview mirror (and/or backup camera) to rewind yourself around curves until you find a shoulder or driveway on which to park.

The citizens of Bainbridge manage this whole thing with grace and even joy – it is part of life on the island – not a have‐to but a get‐to; not a hassle but a charming opportunity to solve the kinds of problems that happen when you build houses in the wake of glaciers.

This is the extended analogy for this section – driving on that unique road. We will return to it at the end, but you should use it for what it is: velcro for your learning. Let the ideas that follow stick to it, reflect off it, contradict it, amplify it, change it. This is how we make meaning; this is how we learn.

Interrupt Interruptions

Immediacy is the condition of modern life, the “new now,” that allows transactions big and small to happen when they are most meaningful and helpful (sometimes instantly, but not always). It occurs when both the actor and the audience deliver and receive what they need at the best time for their purposes (sometimes at the same time, but not always).

Looking at the ways it helps “individual contributors” or “producers” to add value to their organizations offers a good starting point for understanding its power – and why you would want to invest in it.

Let's imagine a business trip to a conference and how immediacy might help an “individual contributor” to do the kind of work that only she can do – unique, creative, and tied to her personality, history, and perspective.

At 5 a.m., before heading to the airport, our traveler can launch a ridesharing app, which, after a few taps of her fingers, will most likely guess where she is going. There's no urgency for her to plan her ride in advance of the time when she is ready to use the car. Instead, she can begin thinking about the work she would like to accomplish during the trip: for example, as a speaker at the conference, representing her company, she might need to finish her slides, and she also might need to advance a time‐sensitive project involving several different departments.

Worry‐free when she enters the car, she can open her laptop or check her phone to begin completing the tasks required for her to advance her work.

On the plane, she can connect – again with full focus – to the Internet and pull what she needs from the cloud. She can review research or data, check in with important contacts, and see responses to questions she sent out the night before via email. All the while, her calendar, also connected to the Internet, can feed her reminders and tasks.

When she lands, she can use another app to figure out the best way to move from the airport to her hotel. She might take a few pictures to incorporate in her slides; she might read an article that gives her an idea for the project.

Arriving early at the hotel, she can ask for the concierge to send her a text when her room is ready. At lunch, she can begin to scan various social media feeds related to the conference, helping her to connect with potential audience members in advance of her talk.

Walking back to the hotel, having been summoned by the concierge, she can dictate notes and thoughts into a transcription app, capturing any insights or conclusions she has developed along the way. She might send them out in a memo later; she might post them to a blog; she might type them into an agenda; she might send them, as notes, to her assistant or team.

There is no need to describe the rest of this imagined trip. Increasingly, many of us live and work like this, utterly connected and increasingly fluid as a result. But we do not often slow down to describe how we work like this…or to tease out the implications.

If you are focused on certain outcomes, as our hypothetical traveler was, you can leverage the immediacy available to you as you travel, as you work in your office or home, and even as you play. Producing genuine, original product – of thought, of thinking, in writing, on stage, in classrooms – basically requires such a shift. In our increasingly networked world, interruptions in momentum, or a failure of context to generate the right resources at the right time, erode excellence. Immediacy, properly channeled, heightens it.

Adjust for Others

Our hypothetical traveler was aided by her level of focus, which was aided, in turn, by several shadow factors that were blended into the background of our narrative: that is, the leaders, salespeople, service professionals, and trainers with whom our traveler had come into contact.

The leader to whom she “reported” most likely helped her to establish clear priorities and offered her the freedom to deliver on those priorities in any way she saw fit. Like a good teacher, this leader had most likely been clear about an expected end point (in school, this is called “backward design”) and open about the path an individual learner would take on her way to that end point (in school, this is called “differentiated instruction”).

The salespeople and service professionals that she met along the way – again, blended into the background of her story – also understood how to show up for her at the times that were most meaningful. They knew how to present, or work though, infrastructures and networks that allowed transactions to occur, for our hypothetical traveler, when they were most meaningful and helpful to her.

In classrooms, effective teachers adjust for the just‐in‐time needs of learners. In business, we can do the same for our clients, customers, and colleagues.