2

WHAT THE NAFTA IS (AND IS NOT)

In 2011 Robert Pastor described the NAFTA as having become a “piñata for pandering pundits and politicians” (Pastor 2011: 3). Indeed, the NAFTA has morphed symbolically into something quite different from what is actually written in the text of the agreement. There are a number of possible explanations for this larger-than-life “persona” the NAFTA has taken on. It was, at the time, a significant undertaking in North America. Just 14 months of negotiation had produced a significant leap forward in formalizing and extending the trading relationship between the three countries. It was not on the scale of the European project, but such a dramatic leap had not taken decades to complete either. Moreover, the NAFTA was significant because it was the largest regional economic undertaking any of the three countries had ever been engaged in, virtually guaranteeing it would generate considerable scrutiny. Equally important, it was the first such agreement anywhere to incorporate two rich, developed economies (Canada and the United States) and a poorer, less developed economy (Mexico) under a single set of trading rules.

It was an experiment that made many people nervous, caused others to look to the NAFTA with great promise and has solidified the NAFTA as a focal point of debate around trade, but also more broadly around North America since the agreement’s inception. One of the central problems confronting the NAFTA in such a political environment has been separating the NAFTA as an agreement from the NAFTA as a symbol. Doing so is not as straightforward as it sounds, since the agreement’s symbolism has so often been tied to aspects of its performance in terms of outcomes: how many jobs did it create, did it foster economic reform, did it drive wages up or down, how much trade did it stimulate, what contribution did the NAFTA make to gross domestic product (GDP) growth, how much did the NAFTA stimulate development?

Every book and article about the NAFTA presents evidence aimed at sorting through all these questions. However, definitive answers have been elusive, because so many elements of the NAFTA co-vary with numerous other variables.

What can be said for certain, however, is that the NAFTA’s proponents oversold what it could do while its opponents claimed its deleterious effects would be far worse than they actually were. Proponents were correct to argue that the agreement would remake parts of North America’s economic landscape for the better. However, politically, some oversold the NAFTA, leading some to expect streets all over the continent would soon be paved with gold. Opponents painted the NAFTA as an economic bogyman that would destroy millions of jobs, suck investment capital south undermine state sovereignty or otherwise destroy life as we knew it.

According to Robert Pastor:

[T]he [1994 Mexican] Peso crisis was a symptom of both the success and inadequacy of the NAFTA. The success was reflected in the expansion in trade and capital flows; the inadequacy was manifest in the lack of institutional capacity among the three governments to monitor, anticipate, plan, or even respond to such a serious problem. NAFTA, in brief, was defined too narrowly, and the three governments paid a price for that myopia, albeit a price that varied among the three countries. Even worse, the three governments have not learned the lesson of 1994; they still apparently fail to understand the many dimensions of the phenomenon of North American integration. (Pastor 2001: 6)

None of that happened, but the NAFTA has been judged on the basis of these extremes nonetheless. The reality is the NAFTA was always much more modest than either its wildest critics or proponents claimed.

Like those before it, this volume about the NAFTA includes the odd table depicting flows of widgets, people and dollars during the life of the agreement. However, the importance of the NAFTA can also be understood beyond the sets of descriptive statistics privileged by politicians, pundits, the press and the public. In fact, one of the most important, and frequently glossed over, intellectual portals for understanding the merits and shortcomings of the NAFTA’s design is by casting the agreement against the larger postwar institutional design of the multilateral trading system and through the neoclassical stages of integration.

The postwar system

The Second World War destroyed what remained of global flows of trade and investment already decimated by the onset of the Great Depression. Chapter 1 notes the intellectual linkage tying economic nationalism to the onset of the Great Depression, the severity of which opened the door to the political nationalism that, in turn, led to interstate violence. One of the most significant flashpoints in the descent into economic nationalism was the notorious Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, in which the US Congress imposed prohibitively high import tariffs on tens of thousands of goods. As other countries retaliated in kind, the collective outcome of these so-called “beggar thy neighbour” policies became a self-defeating downward spiral into global protectionism that many scholars and officials later concluded exacerbated the onset and duration of the Great Depression. As global trade ground to a halt, economic nationalism fuelled political nationalism and, eventually, another world war that smashed what remained of the global economy.

The goal of delegates to the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 was to design a postwar order that would, hopefully, manage international economic relations such that a repeat of the interwar years was unlikely. Although separated by 50 years, the NAFTA and Bretton Woods are deeply linked.

Bretton Woods is most closely associated with the creation of the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, or World Bank). However, Bretton Woods delegates also puzzled over how to reboot the global trading system. Efforts to create a multilateral trading system encompassing more than 100 countries had largely failed by the late 1940s. However, out of that failure emerged a group of 23, mostly Western and developed, countries that formed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1947. The GATT’s more modest structure and membership have, of course, been radically transformed over the postwar period. Indeed, with the GATT’s transformation into the World Trade Organization in 1994, its much larger membership (over 160 countries) and its expanded agenda, the WTO more closely resembles the multilateral organization originally conceptualized at Bretton Woods.

GATT article XXIV and NAFTA

The GATT was a creature of the era in which it was created. Much of the global economy lay in ruins, productive capacities in Europe and Asia had been smashed by war, and the global trading system had become wracked with protectionism. The creation of the GATT was, in part, a reaction to the failure to create a larger multilateral system; a half-measure among a smaller coalition of those willing to set up something – anything – resembling a rules-based trading order (Irwin, Mavroidis & Sykes 2008; Irwin 1995).

The desire to stimulate rules-based trade, of any kind, was so strong that the architects of the GATT included article XXIV, permitting members to conclude customs unions and free trade areas outside GATT rules.

[T]he contracting parties recognize the desirability of increasing freedom of trade by the development, through voluntary agreements, of closer integration between the economies … They also recognize that the purpose of a customs union or of a free-trade area should be to facilitate trade between the constituent territories and not to raise barriers to the trade of other contracting parties …

Provided that; … the duties and other regulations of commerce of … such a union or agreement shall not on the whole be higher or more restrictive than the general incidence of duties and regulations of commerce applicable in the constituent territories prior to the formation of such a union … the duties and other regulations of commerce.

(GATT 1947, article XXIV 4, 5(a))

The NAFTA is one such agreement.

Think about this for a minute. The GATT was set up, in part, to limit the use of the kind of discriminatory trade policies many concluded had contributed to the “beggar thy neighbour” economic nationalism of the interwar years. Yet, within the GATT (since 1994 the World Trade Organization) structure, provision for discrimination through free trade areas and customs unions is embedded within the multilateral structure.

In short, the provisions of agreements such as the NAFTA, or its apparent successor the USMCA, go further than the GATT/WTO, but are inherently discriminatory since, although they might liberalize trade among their members (Canada, the United States and Mexico), those same benefits are unavailable to those outside the NAFTA.

The neoclassical stages of integration

Why did the NAFTA become such a controversial agreement? One place to look for a deeper understanding of just what the NAFTA is – and, as important, what it is not – can be found in the basic conceptual distinctions in the neoclassical stages of integration. Through this same examination of the stages of integration we can further tease out many of the political cleavages swirling around the agreement since its inception.

In both areas – conceptual clarity and the politics of the NAFTA – the central point of analysis can almost always be distilled down to debates over sovereign power flowing from the trade-offs associated with the stages of integration.

There are many good reasons to pursue regionalism, including possible gains from trade, strengthening policy reforms at home, efforts to augment multilateral bargaining power, market access guarantees and geostrategic considerations (Whalley 1998; Baldwin 1997). A number of these motivations were prominent in the economic and political case in favour of the NAFTA, not the least of which was “locking in” governance reforms in Mexico (Hart, Dymond & Robertson 1994: 36–53; Dryden 1995: 340–1, 370). According to the WTO, there are currently more than 400 regional trade agreements in force around the world, the overwhelming majority of them concluded after 1990.1 In part because of their proliferation, but also because of the sheer variety of governance within each of them, economists have increasingly worried about the growth of a global “spaghetti bowl” of preferences arrangements that, for all the trade they liberalize, is generating considerable protectionism and inefficiency (Baldwin 2006; Estevadeordal & Suominen 2005; Bhagwati 1995).

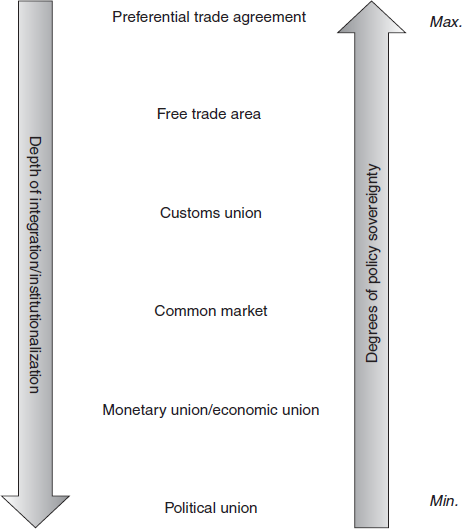

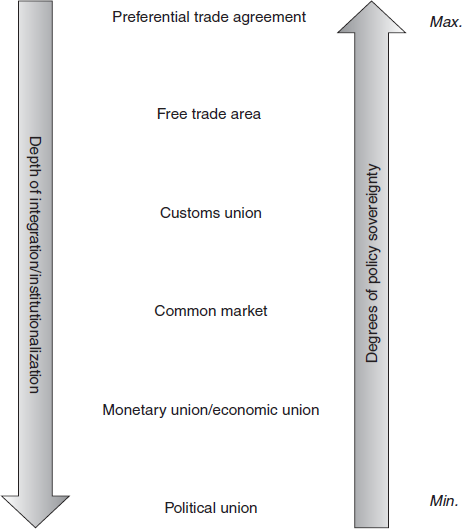

Figure 2.1 Neoclassical stages of integration and sovereignty

The NAFTA is just one of the more than 400 regional trading arrangements notified to the WTO under article XXIV. It also occupies a category of regional governance key to understanding what the NAFTA is and is not. Specifically, Figure 2.1 graphically depicts the neoclassical stages of integration and the trade-offs between sovereignty and institutionalization at ever deeper stages of integration that inherently bring about increasing degrees of pooled sovereignty.

Sorting through how the NAFTA is mixed up in the neoclassical stages of integration is a less common approach to dissecting the politics and economics of the agreement, but no less important to either than sets of statistics.

Preferences arrangements

Preferences arrangements are the most limited kind of trade liberalization permissible under article XXIV rules. Such arrangements take countless forms, but typically involve liberalization or integration that is restricted to a subset of trade between members, or in many cases a single sector. A prime example in the North American context is the 1965 Canada–US Auto Pact, which substantially eliminated tariffs on automobiles and parts crossing the border and revolutionized supply chains and production by effectively eliminating the economic significance of the international border, as auto makers decided where to locate production most efficiently (Anastakis 2005; 2000; Fuss & Waverman 1986). Years earlier, on the other side of the Atlantic, the 1951 Treaty of Paris had created the European Coal and Steel Community among a select group of European countries around, as the title suggests, coal and steel production.2 It was also the foundation of what four decades later became the European Union. Importantly, GATT article I paragraph 2 does not require the elimination of preferences arrangements between countries as a condition of GATT membership so long as the value of that preferences trade is below that negotiated under the GATT itself. So long as the barriers within the preferences arrangements do not exceed tariff rates negotiated among the members of the GATT – the agreement generally liberalizes – arrangements such as the Auto Pact and the ECSC are compliant (Anastakis 2001).3

The terms under which preferences agreements are governed are as variable as the sectors they cover. The Auto Pact, for example eliminated nearly all impediments to cross-border trade in autos and auto parts, but left the private sector to respond to the incentive structure the Auto Pact put in place. By contrast, the ECSC created a supranational institutional arrangement to direct coal and steel production among its members. The reason preferences agreements are considered the shallowest form of integration is that, in most instances, they require the concession of very little sovereignty on the part of members. Although the ECSC pooled sovereignty, it was also like the Auto Pact in that it covered just one sector of the economy – albeit an important one.

Free trade area

One reason for the proliferation of free trade areas is that the standard for WTO compliance under article XXIV is a relatively low bar.

A free-trade area shall be understood to mean a group of two or more customs territories in which the duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce (except, where necessary, those permitted under Articles XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV and XX) are eliminated on substantially all the trade between the constituent territories in products originating in such territories. (GATT 1947, article XXIV 8(a)(i), emphasis added)

Importantly, it is not the case that all trade inside a free trade area is actually free. What “substantially all” means in practice varies by free trade area, as does the depth of the tariff cuts between members. So long as they are more substantial and deeper than concessions offered to member countries in the WTO, members to a free trade area can claim that duties and other restrictive regulations are eliminated on substantially all the trade. There are no established benchmarks for how long free trade area members can allow for the phase-in of these reductions.

The NAFTA actually set a high bar for a free trade area, eliminating tariffs on all goods as of 2009 once the 15-year phase-ins for the most sensitive products (mainly agriculture) had been completed. At the time of its negotiation the NAFTA was considered one of the most advanced free trade agreements in the world, in part because it went some distance beyond standard tariff reductions on goods and services, many of which will be detailed later in this volume.

However, the most important facet of the NAFTA as a free trade area is to acknowledge just how shallow, and therefore limited, the agreement is in terms of its institutional architecture. The NAFTA is devoid of the kind of supranational institutionalism we observe in Europe wherein state sovereignty is pooled. However, we can nevertheless think about the NAFTA’s rules themselves as a set of institutions that govern trade relations between the three countries (North 1991). A long-standing critique of the NAFTA is that it lacks the kind of pooled sovereignty that would facilitate adaptation of the agreement as conditions warranted. There is no independent secretariat, staffed with technocrats to monitor the operation of the agreement. There is no physical building one can visit to learn about the NAFTA. The NAFTA Secretariat is, in fact, just a web portal maintained by all three countries, where one can find the text of the NAFTA, the details of dispute settlement proceedings and communiqués issued by the NAFTA Free Trade Commission (FTC).4 Indeed, each country continues to manage its trade interests under the NAFTA in much the same manner as it always has: out of the respective federal trade departments, agencies and ministries. The NAFTA does stipulate that the Free Trade Commission, comprised of “cabinet-level representatives of the Parties or their designees”, shall meet once per year (NAFTA, chapter 20, article 2001, clause 5), but there is no requirement that the national leaders get together.

The NAFTA’s institutional design is not widely discussed, in part because it lacks some of the teeth that pooled sovereignty brings. Yet the NAFTA does include several important institutional provisions that – albeit shallow – were highly innovative for the time. Several of them, such as dispute settlement, are discussed in some detail in Chapter 6, but none represents a serious compromise of national sovereignty in the form of the creation of a trilateral governance body. Even when the NAFTA’s rules appear to lean in the direction of the binding, pooled forms of sovereignty we see in Europe, a closer look at their operation reveals processes that are ad hoc and sometimes informal and lack any kind of enforcement power beyond the willingness of the member states to implement.

The importance of a lack of pooled sovereignty under the terms of the NAFTA cannot be overstated in the context of the neoclassical stages of integration. The NAFTA went some distance towards substantially eliminating barriers to trade in goods, services and investment flows and imposed disciplines in a number of other areas. Yet, to the extent that the agreement’s liberalizing character brought about a new dynamism to all three North American economies, it did so with a minimalist approach to governance some argue is required to manage that dynamism.

Although the North American idea has always had an intellectual and economic logic to it, that idea and the logic behind it have frequently clashed with the political trade-offs between sovereign autonomy and the benefits of additional cooperation coupled with pooled sovereignty at ever deeper stages of integration. This has historically been a sensitive issue for all NAFTA countries, particularly given the stark asymmetries of power between them. Canada and Mexico, as the smaller parties to the NAFTA, have generally favoured institutionalization out of a belief that independent adjudicatory bodies could “level the playing field” and curb the arbitrary exercise of power by the United States (Anderson 2006; 2019). The United States, on the other hand, has resisted institutionalization beyond that contemplated in free trade areas, in part because it would impose limitations on its sovereign power (see Figure 2.1) (Anderson 2016).

Indeed, the United States has long-standing anxieties about even the shallow terms of institutionalization found in free trade areas, including the NAFTA. Lawsuits have challenged the legality of the NAFTA’s shallow institutional structure under the US constitution,5 conspiracy theorists have depicted the NAFTA as undermining sovereignty, and President Trump pursued its renegotiation in 2017 in part because of his belief that the agreement’s institutional structure forced the United States to do things it did not want to do.

As the foregoing suggests, there is little basis for those fears. However, as the discussion shifts to deeper stages of integration involving pooled sovereignty – something proponents of North American integration championed – it is worth noting the challenges of modernizing a shallow free trade agreement such as the NAFTA as well as the complexities Britain confronts as it contemplates unwinding itself from the European Union. Hint: pooling sovereignty is hard.

The advent of non-tariff barriers

One reason preferences agreements and free trade areas are relatively popular is that the bulk of the liberalization takes place over tariff rates. Tariffs are generally the easiest trade barriers to identify, in most countries via publicly available tariff schedules. Moreover, tariffs come in two basic forms – ad valorem and specific – and are applied at the point of entry (border measures), making them relatively straightforward for parties to begin bargaining over. Ad valorem rates are applied to goods as a percentage of their value; a 5 per cent tariff applied to a $100 product, say, would raise the price of that product in the domestic market to $105. A specific tariff is more like a fee applied to imports: say $10 applied to a product valued at $100, raising the domestic price to $110. Tariffs such as these are readily identifiable and comparatively easy to bargain down.

However, beyond that, trade liberalization becomes more difficult. Box 2.1 contains a list of commercial policies put in place by governments. Tariffs on goods imported into the United States, for example, used to be the single most important source of federal revenue, contributing nearly 90 per cent of all revenue as late as 1861, dropping to less than 40 per cent by 1864 and never again accounting for more than 57 per cent (1890) of federal revenue. By 1992, in the midst of the NAFTA negotiations, tariff revenue contributed only 1.6 per cent to federal revenue (Eckes 1995: 46, 73).

(a) Import tariffs

Two types: ad valorem – essentially a percentage of price; specific – a set level, say $25 per unit.

(b) Import quotas

Vary widely in how they are administered, but are essentially some form of quantitative limit set on import levels. Can also be in the form of negotiated “voluntary export restraints”, such as those negotiated between the United States and Japan over autos in the 1980s.

(c) Technical or administrative restrictions

Health or environmental restrictions; national security provisions or exemptions – e.g. “Buy America” restrictions; cultural sensitivities – e.g. CRTC.*

(d) Government procurement (government spending contracts)

Gives domestic firms advantages over foreign firms in bidding for contracts.

(e) State trading

Essentially barter-style trade between countries – e.g. Canada sells nuclear reactors to China in exchange for something else in return.

(f) Multiple exchange rates

Utilize different exchange rates depending on the product to make imports more expensive in the domestic market.

(g) Subsidies/export subsidies

Everything from direct cash payments to firms for production, to tax incentives, or even offering preferential borrowing terms for the financing of new production (e.g. Bombardier). Subsidies are targeted to make firms more competitive generally, whether in their domestic or foreign markets. Export subsidies are tied to whether a firm sends its products abroad and are designed to make the firm more competitive abroad.

(h) Dumping

Selling your products abroad more cheaply than you would in your home market.

Three types of dumping: sporadic (e.g. a bumper crop of wheat); persistent; predatory (a temporary measure to capture market share and drive competitors out).

Imposed to conserve scarce resources or generate government revenue from an industry deemed a monopolist or highly profitable. Discourages exports for revenue purposes.

(j) Export controls

Usually imposed on scarce goods or environmentally sensitive goods needed in the national interest or perhaps for conservation purposes – e.g. raw log export bans.

(k) Cartel

Organization of producers or producing countries that colludes to restrict output and affect price – e.g. OPEC.

(l) Intellectual property rights

Patents and copyrights; pushed in international negotiations to benefit the holders of the patents.

(m) Offshore assembly provisions

Charge tariffs only on foreign inputs in an effort to boost domestic sourcing (import substitution). Flipside is that it encourages companies to move offshore for assembly.

(n) Rules of origin

Production and assembly requirements applied to production within a preferential trading area such as the NAFTA. Specifies that, in order to qualify for duty-free treatment within and between trading area partners, products must contain a specified percentage of inputs sourced from within the trade area (i.e. from within a NAFTA country).

(o) Supply management agreements

Similar to a cartel arrangement, but the aim is to set long-term production and price levels that will enable industry to ride out fluctuations in the market while keeping steady production levels. Involves the use of stock piling. State trading enterprises, such as the Canadian Wheat Board. And provincial dairy associations and marketing boards regulate entry into the sector as well as production.

* Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, the regulator pursuant to federal legislation around radio/television/telecoms, most often aimed at promoting Canadian content and limiting foreign ownership of broadcasting and telecoms firms.

Although tariffs and quotas are explicitly designed to restrict trade, many others listed in Box 2.1 have other purposes but may nevertheless have some impact on flows of goods and services across borders. Indeed, after the Tokyo Round of GATT negotiations, tariffs were no longer the chief impediments to global trade flows (Balassa 1980; Deardorff & Stern 1981).6 Border measures such as tariffs or quotas gave way to a series of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) or behind-the-border (BTB) measures (items (c) to (o) in Box 2.1) as the most serious impediments to global trade flows.

Regardless of what they are called, the range of measures of a non-tariff or behind-the-border nature are very difficult to negotiate away; they are hard to identify and quantify and sometimes only indirectly affect trade. However, it is also this thicket of complex governance issues that is at the heart of the global trade agenda.

This slightly extended discussion of free trade areas is important beyond its utility in categorizing the NAFTA. Indeed, the NAFTA’s limitations as a free trade area have been part of the rationale put forward for “deepening” North American integration in the direction of more pooled sovereignty in order to deal with an expanding agenda of NTBs (Box 2.1) (Whalley 1998). However, the trade-offs between the efficiency benefits of deeper integration and the loss of sovereignty through the pooling that is required have also exposed the deep political divisions around “next steps” in North American integration.

Customs union

The Tokyo Round of the GATT was the first of the postwar multilateral trade negotiations to grapple with non-tariff barriers, subsidies in particular. The outcome suggested some of the difficulties that lay ahead. As Robert Pastor observed in 1980, “lowering tariffs has, in effect, been like draining a swamp. The lower water level has revealed all the snags and stumps of non-tariff barriers that have to be cleared away” (Pastor 1980: 119). That the purpose of most NTBs is primarily domestic signals that sensitivities around sovereignty will be one of the biggest challenges in bargaining them down in the name of efficiency.

The sheer number and variety of NTBs with impacts on global trade flows has made it difficult to identify them, much less quantify their impact. Among 30 developed countries for which the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) had data in 2013, 30 per cent of all trade was affected by just one category of NTB: technical barriers to trade (TBTs) (UNCTAD 2013: 4; Ferrantino 2006).

One way to begin eliminating NTBs is to advance to a “deeper” stage of integration, such as a customs union. Customs unions can entail the pooling of sovereignty around any number of issues, but are most simply focused on the harmonization of tariff schedules among member countries. That might not seem like a big step, but it is significant for a number of reasons. In a free trade area, member countries maintain their own tariff schedules vis-à-vis non-member countries. Under the NAFTA, Canada, Mexico and the United States maintained their own tariff schedules and customs procedures to be applied to goods from non-NAFTA countries. This then also requires complicated (and inefficient) rules of origin for intra-NAFTA trade to ensure that non-NAFTA goods do obtain tariff-free movement in North America by first entering the country with the lowest tariffs applied to non-members – a topic to be taken up in greater detail in Chapter 3.

A customs union would eliminate the need for rules of origin, harmonize all tariff schedules among NAFTA members and create a single, trilateral customs agency covering all of North America, which would apply the same duties and procedures at ports of entry in all three countries. Most importantly, a customs union in North America would eliminate the necessity of separate inspections and duty application at North America’s current international land borders. Once goods had entered the North American economic space, they would be free to move anywhere on the continent; no additional inspections at El Paso–Juárez or Detroit–Windsor, two of the busiest land borders in the world (Goldfarb 2003; Pastor 2008; Dobson 2002).

The idea of a customs union was never much more than an academic preoccupation in North America until the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States brought some renewed practical thinking about the utility of a customs union for security. In fact, security quickly reanimated the North American agenda for a time, as officials struggled to both secure and facilitate border crossings for legitimate people and cargo (Anderson & Sands 2007; Ackleson & Kastner 2006; Ackleson 2009). The NAFTA left a substantial built-in agenda within the text, complete with 30 trilateral working groups aimed at advancing some of that agenda. Yet the success of these working groups was limited, most falling dormant within a few years of the NAFTA’s implementation in 1994. The post-9/11 imperatives of security renewed thinking about how to animate the post-NAFTA agenda as well.

A customs union could have been part of a common perimeter security strategy in North America that brought relief to the pressures being placed on North America’s land borders with every new security measure, by, at the very least, having those measures implemented at ports of entry around the continent’s edges (Andreas & Biersteker 2014; Anderson 2016).

In 2005 Canada, Mexico and the United States launched the ambitious-looking Security and Prosperity Partnership (SPP), ostensibly aimed at managing the apparent tensions between security and economic openness. Indeed, although security was the driving force behind much of the SPP, the full agenda ambitiously reflected many of the complicated governance issues represented by NTBs in the global trading regime. However, the SPP suffered from a number of faults, including lack of input or oversight from either the public or elected officials (Anderson & Sands 2007: 14–19). The SPP eventually collided with a number of political realities, including the unwillingness of all three NAFTA members, but especially the United States, to move towards the pooled sovereignty that advancing the more ambitious elements of the SPP agenda would have required.

Common market

The failure of post-9/11 initiatives to substantively reinvigorate momentum towards deeper stages of North American integration was a disappointment for some, particularly since the continent’s land borders quickly became reinforced as the main interdiction points for both trade and security purposes. That the infrastructure at many land border crossings was designed and built in the middle of the twentieth century to accommodate much lower levels of commercial activity compounded perceptions that the border was being “thickened” by security (Ackleson 2009; Goldfarb & Robson 2003; Walke & Fullerton 2014; Lara-Valencia 2011).

The disappointment of the post-9/11 period didn’t stop scholars from thinking about what North America could become. Indeed, a significant body of research has accumulated about what a North American common market might look like, starting with increased labour mobility (Rekai 2002). A common market inherently implies significant pooling of sovereignty, since it entails the complete mobility of all factors of production among the members. In effect, a common market in North America would dramatically reduce the economic impact of borders in segmenting labour markets, make passport-free travel possible and harmonize large swathes of labour law, making it easier for nationals of all three countries to work throughout North America.

The efficiency gains from a North American common market are, of course, complicated by the anxieties over sovereignty, especially given the contemporary salience of nationalist populism. Indeed, the idea of deepening North America in the direction of a common market has regularly been fodder for nationalist/nativist conspiracy theories. These are not new anxieties, nor are they limited to North America (Duina & Blithe 1999). In fact, passport-free travel in Europe has been under considerable political pressure in recent years, as migration flows from North Africa and the Middle East have fuelled a reconsideration of the merits of the 26-member Schengen area (Geddes & Scholten 2016: 144–71).

Labour and labour mobility will receive more extensive treatment in Chapter 7 of this volume. However, in broad terms, the NAFTA has steered clear of significantly liberalizing labour markets, doing so on a limited basis only for select categories of business professionals. Moreover, the practical access business professionals from each of the three countries had to those provisions was uneven. More importantly still, the NAFTA never contemplated harmonized labour laws, immigration policies or the pooling of sovereignty necessary to do so.

Monetary union

Although a customs union has only periodically moved beyond the economists’ chalkboard and into the realm of public consideration, the idea of a monetary union in North America has never really escaped the confines of academic theorizing and speculation. Economists have typically been reinvigorated in their speculation about monetary union in periods when exchange rates between the three countries have experienced significant swings. In these periods economists pick up their chalk and argue that a common currency would alleviate exchange rate risk on all sorts of cross-border transactions. Indeed, we can imagine the economic inefficiencies that would ensue if each of the 50 US states, 31 Mexican states and ten Canadian provinces had their own currencies!

The NAFTA went some distance towards stimulating trade among all three countries by moving to eliminate a number of transactions costs linked to the exchange of goods and services, but it never considered transactions costs associated with exchange rates. It was a curious limitation of the NAFTA’s architecture, since many of the commodities traded among the three countries are priced globally in US dollars, and a sizable number of Canadians and Mexicans hold US dollar assets (bank accounts, property, securities), so why not just “dollarize” the entire NAFTA area?

To begin with, although paper currencies have been in wide circulation only since the middle of the nineteenth century, they have acquired a curious cultural sensitivity that makes abandoning them in favour of another tough for some publics to swallow (Gilbert & Helleiner 1999; Meier-Pesti & Kirchler 2003; Risse et al. 1999). The most prominent example of this comes from Europe, where the United Kingdom remained outside the Eurozone after it was established in 1999. Would Canadians willingly turn in their Canadian dollar coins (affectionately known as a “loonie”, because of the loon depicted on one side) or their two-dollar coins (known as “two-nies”, even though no bird is depicted) in favour of the US dollar? What about a new, yet to be imagined, trilateral currency?

However, another set of important hurdles in North America are institutional, in that monetary union would require the pooling of sovereignty around central banking, which none of the three countries has ever come close to being willing to entertain. In a best-case cooperative scenario for Canada and Mexico, they would join with the United States to create a new institution, say a North American Central Bank (NACB), to manage a new currency – the amero, as some have coined it (Grubel 1999). This would entail all three countries giving up their monetary sovereignty – control over their currencies and interest rate setting – to a new continental central bank: a replacement for the Bank of Canada, US Federal Reserve and Banco de Mexico. The obvious comparator is, again, the Eurozone, wherein 19 of the European Union’s 28 members abandoned their national currencies and pooled monetary policy decisions in a new institution, the European Central Bank. As the United Kingdom’s long-standing reticence over Eurozone membership attests, the decision to do so, even among countries of relative comparability and size, is politically fraught (Adler-Nissen 2016).

Such a significant institutional step is complicated in North America by the stark asymmetries among the three countries. Indeed, the politics of monetary union in North America would undoubtedly be anchored in long-standing fears in Canada and Mexico of domination by the United States. In practice, a North American monetary union would likely entail dollarization rather than a brand new currency such as the amero. Instead of a new NACB, Canada and Mexico would end up dissolving their central banks, ceding their monetary sovereignty to the US Federal Reserve and hoping to negotiate terms of influence within Fed governance over the continent (Robson & Laidler 2002; Courchene & Harris 1999).

Political union

The very concept of North American integration has been fodder for conspiracy theorists on both the political left and right. For them, political union is the horrific end goal of elitists who supported the NAFTA as a first step towards the demise of the nation state. The 1988 Canadian federal election campaign, for example, was effectively a referendum on the pending free trade agreement the governing Conservatives had negotiated with the Reagan administration. The opposition Liberals ran a television advertisement featuring an American trade negotiator erasing the 49th parallel on a map of North America.7

The precise identities of the elites driving all this are typically underspecified, but, more than any of the individual stages of integration, it is political union as the logical conclusion to the neoclassical stages of integration that evokes some of the strongest opposition in all three NAFTA countries – and, in recent years, the United States in particular (see Corsi 2007; Dobbs 2004; 2006; 2007). The reason for all this fear is that political union in North America would entail some kind of supranational political governance that would, in full or in part, supplant the power of respective national governments. However, it is important to note just how far away we are from anything resembling such an outcome in North America, and also, then, how far off base certain voices are in stoking fears associated with such. Consider Europe, for example, where the postwar project has far different imperatives and meanings, yet still has considerable distance to go before political union is achieved among member states (Moravcsik 2006; Thirion 2017). As the European project has advanced, it has centralized and bureaucratized considerable areas of social and economic policy in Brussels. Moreover, EU-wide elections for membership in the European Parliament now contend in importance with elections to national legislatures. These disruptions to traditional governance patterns, and the political challenges they have spawned, have prompted efforts on the part of the European Union to ensure the legitimacy of these processes in the eyes of EU citizens (Vause 1995; Edwards 1996), in turn giving birth to an entire academic literature on multi-level governance as the European Union’s efforts have proliferated (Hooghe & Marks 2003; Leibfried et al. 2015; Ansell & Torfing 2016).

In recent years simply consolidating what Europe has achieved in areas such as monetary union has been challenged by wobbly economies in Italy, Spain, Ireland and, of course, Greece. In early 2005 voters in France and the Netherlands stunned everyone by rejecting the proposed European constitution, consolidating all previous treaties into a single document. And, of course, recent migrant flows from North Africa and Syria have cast doubt on immigration policy, particularly in the United Kingdom, where “Brexit” has been fuelled, in part, by public concerns about immigration.

Echoes of the recent cracks in the EU project can be heard in North America, but they are also a reminder of the relative shallowness of the North American project. Each of the NAFTA partners is in the midst of its own experiment with the complexities of federalism, and each continues to work on knitting its respective country together. Pooled sovereignty with each other is not on the table. Canada, for example, continues to struggle with knitting the country together politically and economically, east, west and north. Indeed, Canada’s unique brand of decentralized federalism had necessitated a number of internal arrangements between Ottawa and its provinces, and between the provinces themselves, to establish internal rules of trade. In June 2017 Ottawa and Canada’s provinces finally did so, approving the Canadian Free Trade Agreement – an agreement with striking similarities to the NAFTA.8

The purpose of this chapter has been to set the NAFTA as a “thing” in some categorical context that can then be used to parse out many of its most important elements. The main point is that the NAFTA is a relatively shallow free trade agreement; shallow in that it envisages no pooling of sovereignty in any kind of shared institutional structure. In a lot of ways, this was a completely unsatisfying outcome, because the NAFTA liberalized trade among the three countries, added additional dynamism to an economic relationship that was already robust but did not put in place the kinds of institutional mechanisms that would have allowed the NAFTA to adapt to that dynamism. The NAFTA left over a substantial agenda that, in part, was the victim of the politics of globalization in the late 1990s, which included the infamous “Battle in Seattle” at the WTO ministerial conference in November 1999.

The institutional shallowness of the NAFTA went some distance to assuaging the concerns of those who thought the agreement went too far, but did not exactly keep the NAFTA out of the political spotlight. Indeed, in spite of the agreement’s relatively limited ambition in the context of the neoclassical stages of integration, the NAFTA has routinely found itself at the centre of nearly every political firestorm that erupts about trade.

The NAFTA is, of course, a set of “institutions” in the form of rules governing the liberalization of trade between the three countries. Yet, limited and unchangeable as those “institutions” were, the NAFTA was also innovative for its time in terms of taking on many of the non-tariff and technical barriers to trade (“stumps and snags”) the multilateral Tokyo Round had revealed.

1. World Trade Organization, “Regional trade agreements”: www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/region_e.htm (accessed 10 June 2019).

2. Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany.

3. In 2000 the WTO ruled on some of the last remaining provisions of the Auto Pact, effectively ending preferences not already eliminated by other agreements, such as the NAFTA.

4. See www.nafta-sec-alena.org.

5. See US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, Coalition for Fair Lumber Imports vs. United States of America et al., no. 05-1366, argued 8 September 2006, decided 12 December 2006. This case was largely about the constitutionality of the NAFTA’s dispute settlement mechanisms as applied to domestic trade remedy law. The complaint was dismissed due to the court’s lack of jurisdiction over the issue.

6. WTO. The post-Tokyo-Round average tariff levied on industrial products fell to 4.7 per cent.

7. Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ezj4S73IQ1g (accessed 10 June 2019).

8. See Canadian Free Trade Agreement: www.cfta-alec.ca (accessed 10 June 2019). See also the New West Partnership, a subfederal, regional integration scheme among four western provinces: www.newwestpartnershiptrade.ca (accessed 10 June 2019).