Vice Admiral Tovey knew that the Germans were planning a major operation, and he knew it would involve a sortie by Bismarck. Increased German radio activity suggested that a sortie was imminent, On the morning of 21 May Tovey had confirmation that the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen were on their way, having been sighted in the Kattegat the previous evening. Hours later the German ships were spotted at anchor near Bergen. Tovey laid his plans accordingly.

Essentially, to reach the North Atlantic, the German Seekampfgruppe had to pass through one of three routes. The first was the Denmark Strait, between Greenland and Iceland, while the second lay between Iceland and the Faeroes. Either of these two routes was considered likely, and therefore needed blocking. The final route was between the Faeroes and the Shetland Islands, but this route was considered less likely as the passage lay close to the main British naval base at Scapa Flow.

Another option available to the Germans was to linger in the Arctic Circle, having rendezvoused with one of their tankers. They could then simply wait for Tovey’s major warships to return to port to refuel, and then make their move.

Tovey needed to block all these routes, especially the Greenland–Iceland–Faeroes gaps. Rear Admiral Wake-Walker’s cruisers Norfolk and Suffolk were already patrolling the Denmark Strait, while the light cruisers Arethusa, Manchester and Birmingham were in place patrolling the Iceland–Faeroes gap. Just after midnight Tovey ordered Vice Admiral Holland’s ‘Battlecruiser Force’ to sea – Hood and Prince of Wales, escorted by six destroyers. Holland was expected to lie to the south of Iceland, where he could intercept the Germans if they were sighted trying to pass through either of the two gaps. The King George V, accompanied by Renown, Victorious, four cruisers and seven destroyers formed a second line of defence, lying to the south, ready to steam towards the enemy when they were sighted. Apart from that, and the stepping up of reconnaissance flights, all Vice Admiral Tovey could do was wait for the enemy to show their hand.

Rear Admiral Wake-Walker, pictured on board his flagship HMS Norfolk. A torpedo specialist, he was regarded as the most able cruiser commander in the Royal Navy. However, he was criticized for not showing more aggression in his shadowing of the Bismarck.

A British lookout on board HMS Suffolk, photographed at his station while she and Norfolk were patrolling the Denmark Strait. While both cruisers were fitted with radar, the sets were temperamental, and so sharp-eyed lookouts remained indispensable during the campaign.

Admiral Lütjens had very clear-cut orders and a well-defined mission. He was ordered to break out into the Atlantic Ocean, and then to attack enemy convoys. The timing, duration and scope of the operation were left to his discretion. He was to avoid taking risks with his ships, which meant where possible he was to avoid fighting enemy capital ships. However, the orders also allowed taking risks if they offered a suitable prize – the destruction of an enemy convoy. The written orders sent to him by Generaladmiral Otto Schniewind and approved by Großadmiral Raeder were extremely detailed, and well worth repeating:

As soon as the two battleships of the ‘Bismarck’ Class are ready for deployment we will be able to seek engagement with forces escorting enemy convoys and, when they have been eliminated, destroy the convoy itself. Just now we cannot follow that course, but it would soon be possible, as an intermediate step, for us to use the battleship Bismarck to distract the hostile escorting forces, in order to enable the other units engaged to operate against the convoy itself. In the beginning, we will have the advantage of surprise because some other ships involved will be making their first appearance, and, based on his experience on the previous battleship operations, they enemy will assume that one battleship will be enough to defend a convoy.

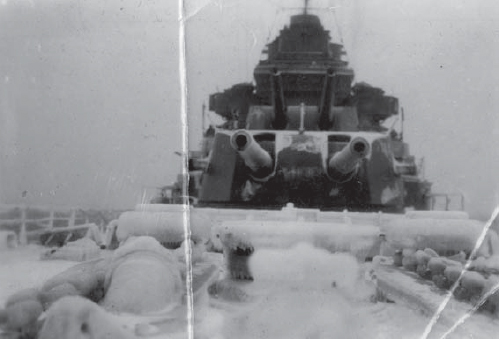

Wake-Walker’s two cruisers were operating on the very edge of the Arctic pack ice. Although taken after the Bismarck operation, this rare view of the forecastle of HMS Suffolk reflects the even harsher Arctic conditions encountered during the Arctic convoys. (Sullivan Family)

At the earliest possible date, which it is hoped will be during the new moon period of April, the Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen, led by the Fleet Commander, ought to be deployed as commerce raiders in the Atlantic. At a time that will depend on the completion of the repairs she is currently undergoing, Gneisenau will also be sent into the Atlantic.

The lessons learned in the last battleship operation indicate that the Gneisenau should join up with the Bismarck group, but a diversionary sweep by the Gneisenau in the area between Cape Verde and the Azores may be planned before that happens. The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen is to spend most of her time operating tactically with the Bismarck or with the Bismarck and Gneisenau. In contrast to previous directives to the Gneisenau–Scharnhorst task force, it is the mission of this task force to also attack escorted convoys. However, the objective of the battleship Bismarck should not be to defeat in an all-out engagement enemies of equal strength, but to tie them down in a delaying action, preserving her own combat capability as much as possible, so allowing other ships to attack the merchant vessels in the convoy. The primary mission of this operation also is the destruction of the enemy’s merchant shipping; enemy warships will be engaged only when the situation makes it necessary and if can be done without excessive risk.

The operational area will be defined as the entire North Atlantic north of the Equator, with the exception of the territorial waters of neutral states. The Group Commands [i.e Commanders of Baltic or Norwegian theatres] have operational control in their zones. The Fleet Commander [i.e. Lütjens] has control at sea.

During last winter the conduct of the war was fundamentally in accord with the directives of the Seekriegsleitung… and closed with the first extended battleship operation in the open Atlantic. Besides achieving important tactical results, this battleship operation shows what important strategic effects similar sorties could have. They would reach beyond the immediate area of operations of the theatres of war. The goal of the war at sea must be to maintain and increase these effects, by repeating such operations as often as possible.

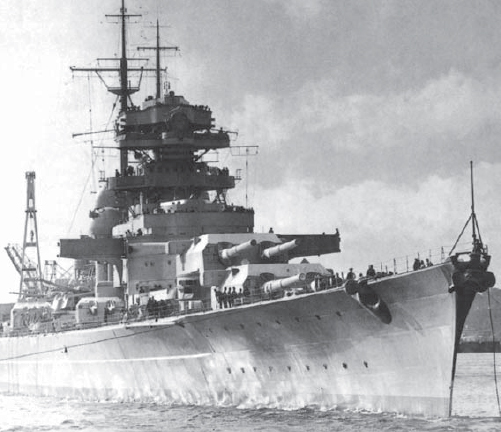

The battleship Bismarck, lying at anchor just off the quayside at Gotenhafen, shortly before the start of Operation Rheinübung. At this angle her sleek, graceful lines are clearly visible – a beautiful but deadly warship, the pride of the Kriegsmarine.

We must not lose sight of the fact that the decisive objective in a struggle with England is to destroy her trade. This can be most effectively accomplished in the North Atlantic, where all her supply lines converge, and where, even in the case of disruption in more distant areas, supplies can still get through via the direct sea route from North America.

Gaining command of the sea in the North Atlantic is the best solution to this problem, but this is not possible with the forces that at this moment we can commit to this purpose, and given the constraint that we must preserve our numerically inferior forces. Nevertheless, we must strive for local and temporary command of the sea in this area and gradually, methodically, and systematically extend it.

During the first battleship operation in the Atlantic, they enemy was always able to deploy one battleship against us, and protect both of its main supply routes. However, it became clear that providing this defence of his convoys brought him to the limit of the possibilities open to him, and the only way he could significantly strengthen his escort forces is by weakening areas important to him or by reducing convoy sailings.

These orders reveal a lot about the way Raeder and Schniewind were gradually modifying the way the major surface units were used. In 1939 the Graf Spee was largely left to her own devices, and used in a similar manner to the way German light cruisers had been used as surface raiders in 1914. Subsequent sorties had become increasingly complex, as the German capital ships had to break through the British cordon which ran from Greenland to Orkney, and then sustain themselves for a limited spell in the midst of Britain’s transatlantic shipping lanes, before returning to a friendly port.

In the Operation Rheinübung orders, the emphasis was still on commerce raiding, but for once the German task force would be powerful enough to engage protected convoys directly, especially if the escorts were merely destroyers or cruisers. This is what was meant by ‘without excessive risk’. However, German naval intelligence was well aware that several convoys were being escorted by British battleships, and Raeder was unwilling that Lütjens be drawn into a stand-up duel with these powerful ships. He left the operational decision of where and when to attack to Lütjens, but it was clear that the main object of the operation was to sink enemy merchant ships, and so help bring Britain to her knees through the strangling of her mercantile lifelines. Risking major German surface units in surface actions against enemy battleships was both unnecessary and risky.

Finally, the intriguing passage about control of the seas is misleading. Raeder and Schniewind weren’t contemplating the destruction of the British Home Fleet. That would have been nigh-on impossible. Instead, they were advocating the establishment of temporary control of the transatlantic sea lanes by forcing the British to keep their convoys in port until the German task force withdrew. This establishment of temporary naval dominance could then be repeated during future operations, until the whole convoy system was brought to a halt.

Admiral Lütjens read all this, and made his own plans. He was also well aware that once he left Norwegian waters, he and his men were on their own.