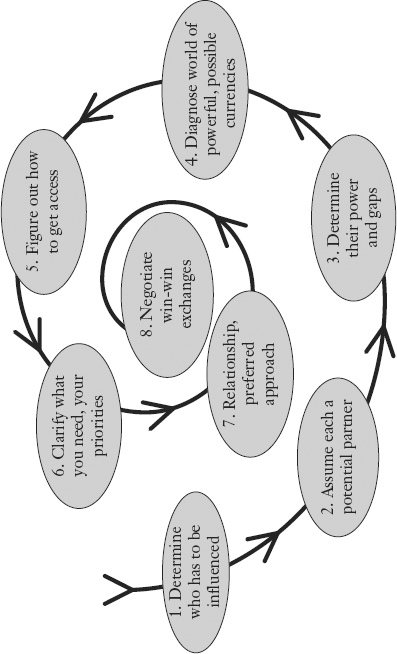

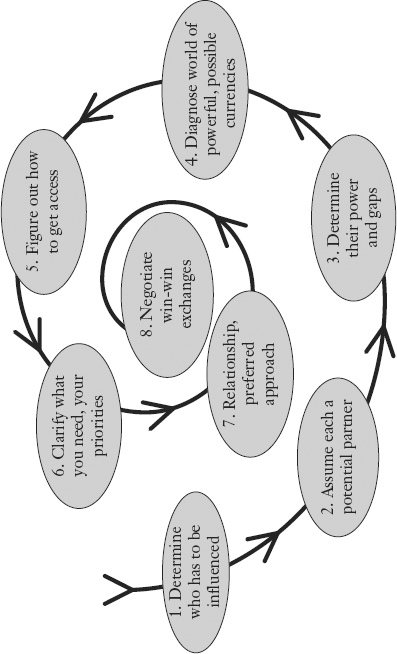

FIGURE 4.1 The Cohen-Bradford Influence Model (Expanded to Focus on the Powerful)

The shortest summary of how influence works is that everyone expects to be paid back. People allow others to influence them because they believe they’ll get something valuable in return. Although it sounds a bit cold—as though the only reason people do anything is out of self-interest—the things that people care about vary greatly. Their desires range from the seemingly selfish—“becoming more able to give orders”—to the purely generous—“enjoying the feeling that comes from seeing others prosper.”

How does this play out in organizational terms? Influencing a powerful person can be crude (“Support me on this or I will reveal your manipulation of booked sales”) or subtle (“Wouldn’t it be useful to be known as an early supporter of innovation?”); noble (“This project will help save lives”) or raw (“Can you really afford to be seen as blocking our best talent?”). Whatever form it takes, influence always involves reciprocity and exchange in which the powerful person or group is willing to be influenced because they benefit in some way. Friends and close colleagues assume that sooner or later, one good turn deserves another. With those who we don’t know as well, we might have to make the exchange much more explicit and immediate. But some form of reciprocity and benefit in return for giving what is requested always undergirds influence.

Everyone acts upon this tendency; reciprocity is the social glue that holds relationships together. But when you don’t seem to be able to influence effectively, a model can serve as a reminder or checklist. Although the concept of exchange is fairly straightforward, the actual process is more complicated. When you already have a good relationship with another person, you don’t have to overanalyze the situation or your approach. You just ask, and the colleague will respond if he or she can.

However, often it can be more difficult in other situations to influence a person or group, and you need to use a more deliberate and conscious approach. That is why this influence model—a careful diagnosis of the other’s interests, assessment of the resources you possess, and attention to the relationship—can be so valuable. It’s especially helpful when you’re faced with an anxiety-provoking situation like making a risky new investment, introducing a product, or outsourcing a contract. These scenarios tend to limit your focus and the alternatives. The model therefore prompts you to stop and consider what steps you must take to gain cooperation.

We begin with an evolution of the Influence without Authority model that we presented in previous books that we now apply specifically to the powerful. We flesh this out with an example of how to use the model when dealing with a powerful boss. We discuss each step in detail (see Figure 4.1). The eight steps of the model are as follows:

FIGURE 4.1 The Cohen-Bradford Influence Model (Expanded to Focus on the Powerful)

This step is fairly easy when you’re trying to influence your boss. Just keep in mind that your boss must answer to a boss (or two, or three) of his or her own—who also needs to be influenced. It’s also not always so clear nowadays exactly who everyone’s boss is (as in matrix organizations or those geographically dispersed). This can become increasingly complicated when you’re tackling a complex issue with senior people both in and outside of the organization. Who is the decision maker? Who influences that person? If you don’t pick the right person or people, you risk wasting your efforts.

One of the greatest challenges you’ll encounter is trying to influence someone who doesn’t seem interested in cooperating. But rather than dismissing that person, assume that everyone you want to influence could be a potential partner—if you work at it. Begin by assessing whether you could form a working alliance with someone by determining whether you have any overlapping interests. You can use this same approach with your manager as well; if you assume that managers are partners with their direct reports, then the responsibility to make the relationship mutually beneficial belongs to both of you.

We observed a common problem among many who have tried to influence powerful people and at first were not successful. After one or two failed attempts, the would-be influencer begins to attribute something negative to the target person or group. Whether it is a growing conviction that the other party has a deficient character (perhaps they see the other person as “just not smart/caring/farsighted enough to see the benefit”) or a suspicion of motives, they’ll deem the unresponsive party as deeply flawed. The problem is that even though the would-be influencer doesn’t voice this attribution, it shows through in subtle ways—and creates even more resistance. It is very hard to influence people who may sense that you think they are flawed or worse.

This is why it’s best to see the other person as a potential partner. This can prevent you from too readily disregarding the other person and reminds you to look for mutual interests around which to collaborate. You give partners the benefit of the doubt when things aren’t going well, and redouble your efforts to help the other person achieve his or her goals—even when their interests are not obvious. Although it’s clearly easier to do this with some people than with others, you can never be sure how resistant the powerful person will be until you approach him or her directly.

Example of Converting a Difficult Boss into a Partner: Dealing with Dr. Death

Consultant Matt Larson tells the story of dealing with a seemingly impossible person when he was recruited by a client of the large financial services firm where he worked:

I had been recruited by CONSULTMORT, and was in the unique position of having the vice president of operations as my number one team member. This was unusual, since she ranked higher than me . . . But limited resources and a high-profile client required that the VP become involved.

Everyone in the organization feared this woman; her “charming personality” had even earned her the nickname “Doctor Death.” As one of the most powerful people in the organization, she controlled all the resources for our service model. She also made people look foolish regularly—and I did not want to start off my career at CONSULTMORT by getting added to that list.

The man I replaced as the project head in my new role had a particularly awful relationship with Doctor Death—which didn’t help me start off well. I received advice from other leaders—none of whom had been able to establish a positive relationship with her. So I decided to take a more (junior) partner-like approach.

My first step was to defer to her. I let her know that I recognized she was the expert around CONSULTMORT from the moment I started, and asked her opinion on my interaction with the client, which seemed to disarm her. “Dr. Death” needs to be recognized as the smartest person in the room, and I had no problem doing that—especially as the new kid. I wanted to do whatever it took to do the job correctly.

Once appeased, she started granting me latitude on the way I managed things. That allowed me to connect with and influence other team members. And although I would rather have eaten paint chips, I also began to develop a personal relationship with her. I spoke about myself in a self-deprecating way, which made her laugh—and share bits and pieces of herself. I wasn’t a fan of her humor, but I laughed when I knew it would please her. I wasn’t being inauthentic; I just needed this person to like and respect me to make my life easier and the project successful.

We both worked incredibly hard from the beginning, into the early hours of the morning—which she respected. I asked her if there was any work I could take off her plate or do to make the project go easier for her. She always said no, but my offers led her to see me as an asset—not as the adversary she sees in most people.

Doctor Death soon started telling people that I could handle things without her—something she hadn’t done with the former project manager. This gave me more room to empower employees who previously feared her wrath. We delivered the project on time, and with an amazing amount of support from this woman. While I credit her for its success, I also credit myself for stroking her ego enough to allow me to get the actual work done.

Although getting past his boss’s offensive personality wasn’t easy for Matt, he did manage to develop a modest kind of partnership with her. Because he kept an open mind and showed genuine interest in her, he discovered qualities he hadn’t expected. He showed how crucial it is to avoid stereotyping someone with a gruff exterior. Even the most powerful person has needs, interests, and vulnerabilities, no matter how hard he or she tries to hide them. If aspiring partners can show some vulnerability, it makes it easier for the potential partner to relax.

A helpful perspective to take is: “We are going to be partners who can mutually influence each other, even though you don’t yet know it. But I am going to show you how this arrangement will benefit you and the organization.”

The challenge is to keep this perspective even when you aren’t sure about the basis for the partnership. Such a positive and supportive assumption, although unspoken, can prompt dialogue that might otherwise have quickly short-circuited possibilities.

The degree of the other person’s power will determine how you respond. Relatively high power requires more deference, formality, and slower relationship development. A lower differential of power might allow for more informality, directness, and egalitarian style. As always, be careful that you don’t attribute more power than the other person has—as we warned against in Chapter 3—and do not underestimate your own potential power. Think about what you have to offer (or withhold) that can help you gain influence.

Because power can be a result of either a person’s organizational position or their personality, determine in this particular instance whether it’s either or both. If positional/structural, what resources does this person actually control? In turn, what access do you have to relationships, information, resources (which are ultimately the source of all organizational power)? How can this help you determine what you can do to diminish the power gap?

If the person’s power is personality-based, is it because of the particular qualities this person has—or is it just because others have assumed the person is powerful, and have never tested this? Some individuals whom others fear actually turned out to be quite isolated from their organization. Once you determine this, you eliminate the power attributed to them.

The following are other questions you can ask to help determine a person’s level of power:

You must look at all of these power factors with an eye toward your own sources of power. Have you been correctly assessing your own power? From this analysis, determine how large the gap is—and what does it tell you about the higher-power party’s likely resistance and responses?

The next step in the influence model takes you deeper into the power analysis.

To be able to make compelling offers for exchange, you want to know what the other person values. We call these currencies, because they represent what can be exchanged. This isn’t always easy to determine. If it’s someone with whom you have worked for a long time and know well, you can probably figure out what they value most. Some individuals’ currencies are reasonably obvious. However, the further the person is from you, the more challenging is the task of discerning his or her currencies.

Though personality plays a role, what people tend to value at work often has to do with their situation. If you can determine how “their world” works, you’ll be able to discern their currencies. You may want to test your assumption before acting on it; you’ll know by the response if you’re in the right territory. Of course, you can always ask the other person if you have a friendly relationship with them: “I need to understand better what matters to you so that I can be sure you get benefits from our collaborating on this task.”

This can be difficult sometimes. Although most people continuously broadcast what is important to them, you must listen very carefully to their language and tone. These things usually hint at what this person values, which will help you determine any overlapping interests. There are also external sources you can check, such as public records, speeches, public policy statements, or industry information. The more you can learn about this person’s possible interests, the better your chances of finding something valuable to exchange.

You can also examine the organizational forces operating on the person. People respond to a number of conditions present in their particular professional situation; so think about how each of these conditions determines likely currencies.

Some sources for deducing probable currencies are:

If you get stuck, consult with someone who has perspective on the boss or context; you may need a bit of distance to find the openings. Of course, keep in mind that this advice may be counterproductive or not helpful, as it was in the case of Matt and Dr. Death. Know your sources, and listen for anything that indicates that these people may have had a hand in perpetuating conflict.

Most people vastly underestimate the number and range of currencies they can actually command for use. Table 4.1 displays a list of common currencies in organizational life that specifically take powerful people into account—almost all of which are available to anyone. Only some “hard currency” task resources might be difficult to generate; if you don’t have a budget or personnel working for you, and that’s what the person wants in exchange for help in supporting a project, then you can’t immediately trade. No one wants all of these; nevertheless, even powerful people have broad portfolios of currencies they value. If you haven’t got one thing, you might be able to find another.

TABLE 4.1 Currencies Frequently Valued in Organizations, with Emphasis on the Powerful

| INSPIRATION-RELATED CURRENCIES | |

| Vision | Being involved in a task that has larger significance for unit, organization, customers, or society; chance to make a large difference |

| Excellence | Having a chance to do important things really well |

| Moral or ethical correctness | Doing what is “right” by a higher standard than efficiency |

| TASK-RELATED CURRENCIES | |

| New resources | Obtaining money, budget increases, personnel, space, and so forth |

| Challenge/learning | Getting to do tasks that increase skills and abilities |

| Assistance | Receiving help with existing projects or unwanted tasks |

| Organizational support | Receiving subtle or direct assistance with implementation |

| Rapid response | Getting something more quickly |

| Autonomy | Ability to work without close supervision; not have to answer to others |

| Information | Obtaining access to organizational or technical knowledge; being “in the know” |

| POSITION-RELATED CURRENCIES | |

| Recognition | Acknowledgment of effort, accomplishment, status, or abilities; reaffirmation of importance |

| Visibility | The chance to be known by important people, higher-ups, or significant members of the organization |

| Reputation | Being seen as competent and committed; having integrity or national prominence |

| Insiderness | A sense of centrality, of belonging, a member of the elite |

| Contacts | Opportunities for connecting to other powerful people |

| RELATIONSHIP-RELATED CURRENCIES | |

| Acceptance/inclusion | Feeling closeness and friendship; not being constrained by obligation |

| Understanding | Having others listen to your concerns |

| Personal support | Receiving personal and emotional backing, understanding the loneliness of a driver |

| Trust | Being ready for disclosure, assumed competence, delivering on commitments |

| PERSONAL-RELATED CURRENCIES | |

| Self-concept | Affirmation of values, self-esteem, and identity; confirmation of their power or bragging rights |

| Gratitude | Appreciation or expression of indebtedness |

| Ownership/involvement | Ownership of and influence over important tasks |

| Comfort | Avoidance of hassles |

Note: This table appeared in both editions of Influence without Authority by Cohen and Bradford. It was originally derived from organizational observations over many years, with the five categories consolidated from much longer lists.

Even though your boss is generally easier to access than other higher-powered individuals, an overloaded or geographically distant supervisor can make this difficult. One example of this difficulty occurred with some managers at Montefiore Hospital; they admitted that the only way they could get any time with the incredibly busy, world-famous doctor who was their director was by studying his schedule, then hanging out near his office looking like they were reading the bulletin board, so they could bump into him and quickly do business as he was leaving or arriving. Bosses who live in different places from their direct reports can be hard to access for extended conversations.

There are a variety of ways to get around this problem. Finding the answers to a few questions will help: To access this person, do you have to get through a gatekeeper, with whom you will need to develop a relationship? What media do they use to get information? Would they prefer a handwritten note? E-mail? Social media? Are there conferences they attend, or clubs, boards, or charitable activities in which they participate? Are there friends who have access that you can influence to help? It can require a campaign, which is just as systematic as any other business activity—but don’t be afraid to undertake this.

It’s not always easy to determine what you want from a potential partner. Asking the following questions can help you figure this out:

Know your core objectives; this will prevent you from getting sidetracked into pursuing secondary goals. What are your priorities among several possibilities—and what are you willing to trade off to get the minimum you need? Do you want cooperation on a specific item, or would you settle for a better relationship in the future? People who desire influence frequently fail to distinguish their personal desires from what is truly necessary on the job—which creates confusion or resistance. For example, if you merely want to be seen as the smartest person in the room all the time, your personal concerns might interfere with more important organizational goals. (Former president of Harvard Larry Summers reportedly suffered from this problem and created massive faculty opposition because he had to win on even minor matters—not a great strategy when dealing with Harvard professors.) Would you rather be “right” or effective?

A good prior relationship makes it easier to ask for what you want without having to prove good intentions. If, however, the relationship has a history of mistrust—or no history whatsoever—proceed with caution. You will need to build the requisite credibility and trust required to engage.

Every person has ways in which they prefer others relate to them. Some like to see a thorough analysis before beginning a discussion; others would rather hear preliminary ideas and get a chance to brainstorm. This isn’t about the style you prefer. If you operate according to the other person’s inclination, you will have more influence.

For example, ask yourself the following about your boss’s style: does he or she prefer openness, brevity, warmth, formal distance, overt respect? Does he or she focus on task and relationship first, or data and conclusions first? Over the years we have developed what we call the 15 percent rule: be 15 percent (that is, just a little) more open or vulnerable than you think the other person is ready for. This may require coming across as being tougher, more direct, terse, relaxed, more (or less) certain, or something else that isn’t necessarily automatic behavior for you.

Everyone responds better when they are approached in ways that they prefer. In this sense, as in many others in the influence process, it is better to follow the Platinum Rule rather than the Golden Rule: instead of “do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” it is often more effective to “do unto others as they want to be done unto.” As George Bernard Shaw pointed out, after all, they may have very different tastes!

For example, consider the experience of the head of production, Juan, at a furniture manufacturing company. According to Juan’s chief executive officer (CEO), “He drives me crazy. I am walking down the hall and he grabs me and asks for $55,000 for a new cutting machine. If he would only write me a memo giving the details, of course, I would agree; but now I want to resist.” Juan is operating in production world mode—in which he must make decisions immediately. He trusts his instincts rather than financial analysis, which Ken clearly would prefer. If Juan reflected, he would realize that the CEO, who came up through finance, would want facts and figures cleanly laid out. Juan lost influence because he related in a way in which he—not the other person—was comfortable.

Once you have determined what goods or services can be exchanged, you are ready to offer what you have in return for what you want. Your approach depends on the following:

Planning for an actual exchange can be a challenge. When dealing with your boss, you have the advantage that a part of the formal role is to think about how to help you be most productive. Sometimes it is possible to just have a direct offer: “If I do X, then will you do Y?” But many bosses (and especially those farther up), take offense to being “bargained with.” They assume that you doing X is part of your job, and therefore the behavior should not be offered as something to exchange. An explicit request can feel like “arm’s-length negotiation” not appropriate to the boss-subordinate role—and the resentment that ensues can create distance between you and your boss.

But let’s suppose your work requires some additional support. You can ask for it in a way that includes the boss’s goals: “I would be glad to take on that project. However, that is going to require some additional expertise in order to make it work well. Can I utilize Denise who is knowledgeable in that technology to assist me?” You are not making the demand just because you want to get “paid” for your effort, but because it will help improve the final result.

As we have stressed, speaking to your boss’s needs is more likely to lead to a successful outcome. For example, “I realize the pressure you are under from your boss on the numbers, so I will more closely manage to budgeted targets. However, in order to do that, I need to eliminate some of the busywork we now do that really isn’t crucial. Can we stop doing X and Y in order to free me up to hit these critical targets?”

In many cases, you can “give two for the price of one.” Is it possible that what you want is also in your boss’s best interests? For example, let’s say you want more discretion. Rather than saying, “I would be glad to take on that project if I can have autonomy on how to achieve it” (a “bargain” your boss is likely to reject), you could say: “Taking on that new project is fine. Presently, I have to check a lot of details with you, which wastes your time and is a bit frustrating for me. Can we agree on the critical issues that require check in? This will keep me from loading you down with all the details and free me up to do this important project.”

Often the agreement is more implicit. Suppose it’s crunch time, and you are working overtime. You don’t say so, but you expect some compensation in the future. There is a problem, however, with such implicit agreements. If you fail to articulate this expectation, it’s possible that your boss has a different understanding of what you want. Is there a way that you can convey the currency in which you want to get paid? For example: “I know that there is a lot of grunt work that needs to get taken care of during this crisis and I am more than glad to do it. I hope that when the pressure is off, you will look for ways to give me more challenging assignments.”

These efforts are part of ensuring that the exchange is equitable. Are you getting justly compensated for your efforts? Sometimes it is smart to invest—go the extra yard to build up goodwill. But whatever the currencies (and whenever the payment), each side needs to feel that over time it is fair. The problem is that the requester is likely to underestimate the cost to the other, and the recipient of the request is likely to overestimate the benefit to the requester.

How do you protect yourself from being short-changed and convey the cost without sounding like you are whining? Be careful that you don’t send the wrong signals. Here’s an example: On Friday afternoon, your boss drops a big assignment on your desk that is due Monday morning. You cheerfully take it up, because you have no choice—even though you had personal plans that weekend that you now have to cancel. On Monday morning, you hand in the completed work to your boss. She thanks you, but do you say, “Oh, it was nothing”? That would convey that you don’t expect much compensation (but wouldn’t you be upset if you weren’t fairly “paid”?). As we said, you don’t want to whine, but there’s nothing wrong with being honest. It might be enough to say, with a smile, “Yes, it took the weekend, and some flak at home; but I knew how important it was and wanted to help.”

Sometimes you don’t discuss the exchange; you just see what you need to do to get the kind of response you prefer, and start doing it, trusting that reciprocity will kick in as your efforts are noticed and appreciated.

Think about dual goals that align with the strategy you use—goals that will get you what you want, and help you achieve a partnership with your boss or higher-up. Don’t win the battle but lose the long-term war because you have made your relationship more distant and hierarchical. It is always better to frame an agreement in positive terms that put the burden on you: “Good, so you can include me more when I (deliver X, or demonstrate greater unit concern, or learn to do Y, etc.)”. That is part of deferring to the senior partner’s role, but it also places responsibility on you, which makes the other person less defensive.

And always give the partner an out: “I know you can’t guarantee a promotion/particular position or assignment/much greater availability, but I will keep my word, and trust that it will work out over time.”

This model also can explain how people lose influence, and therefore fail to become a partner:

Ways to Lose Influence

With all this said—you don’t have to get it perfectly the first time. This model also lets you recover when you initially hit a dead end. To help make these concepts more concrete, we describe in the next chapter a situation involving a controlling boss that seems impossible to overcome. You’ll see how Doug, the direct report, was able to turn things around using this model.