CHAPTER 5

The Influence Model at Work

Moving a Tough Boss

Is there any way to resurrect a relationship that seems to have “gone south”? The following actual situation illustrates how using the Cohen-Bradford Influence Model can turn around what appears to be an irreconcilable impasse. (One of the authors was able to debrief each of the parties; the dialogue is reconstructed from their combined memory of the conversation.)

This example involves Warren, the president of U.S. Operations at a large, multinational corporation, and Doug, the national sales manager for the United States who reports directly to Warren—and who isn’t happy about how Warren manages him. The two men had a conversation about the sales operation and it did not go well. Doug then decided to go to Warren’s office again to discuss their troubled relationship—and the discussion turned out worse than their earlier conversation.

Doug: Warren, have you got some time? I want to talk about that meeting we had the other day. We need to deal with the way we work together. I think it’s interfering with our ability to get things done.

Warren: You’re probably right about that. Go on.

Doug: I’ve been in sales for over 15 years now, but you treat me like a new hire, and question my judgment every time I do something. I’m a national sales manager, and I want to make decisions in my own area. You seem to be constantly looking over my shoulder and micromanaging me.

Warren: Well Doug, now that you’ve mentioned it, I can’t always trust your judgment. If I just listen to what you tell me, I’d have to believe that your sales force can do no wrong. I never really get the whole story from you—just the good news. I only seem to hear the problems in sales when I dig for them myself.

Doug: Do you want news bulletins from the front line every 5 minutes?

Warren: No Doug; that’s not the issue. Trouble is you go off and make important decisions on your own that I only hear about when it’s too late. You never even ask my advice about anything.

Doug: You don’t give me the chance, Warren. Take last month when I was trying to deal with Marty’s poor results. You got word of it somehow and you jumped in before I’d figured out how I was going to handle it.

Warren: But Doug, you’ve never given me any bad news about Marty. Like I said, when you only tell me the good stuff about people, you imply that they can do no wrong. I have no sense how big the issue is when I hear about these situations; I need to find out what’s going on.

Doug: Well, if I do give you the bad news, it haunts the person forever. I’ve got to protect my people. It’s incredibly difficult to change your mind once you’ve locked in an opinion.

Warren: You’ve got to be able to look beyond your own department’s interest. You only see things from the sales point of view.

Doug: It’s my job to represent sales! If I don’t do that, who’s going to? Besides, you never listen to me or support me, so I have to push.

Warren: Yes, representing sales is part of your job—but only part. I need you to be a team player with an open mind, not just an advocate for your own limited perspective.

Doug: Okay. Okay. I could be a better team player. But my team feels like they’re all stuck in left field.

Warren: Well they’d feel less out there if you involved me more frequently. I can troubleshoot and share the big picture with them if you were less protective of your turf.

Doug: I think you’ve missed my point.

Warren: I guess we’re just very different people with very different management styles.

Clearly, these two are not in a good place. Doug has given up on trying to change the conditions with Warren. But all is not lost. The issues are out on the table; however, both men are convinced that the other refuses to change. If they don’t address the situation, the best they’ll have is an arm’s-length relationship marked by low trust and little mutual assistance. Before exploring how they can fix this situation, we should explore what went wrong. The influence model gives us some clues.

1. Doug is not seeing Warren as a potential partner. Warren offered an opening to Doug (“I can troubleshoot and share the big picture”), but Doug didn’t hear that. Instead, he sees Warren as a micromanager who can’t be influenced. And although Warren did seem a bit difficult to influence, Doug didn’t attempt to determine whether this was as absolute as he thought.

2.

Doug didn’t try to understand Warren’s world. Part of the value of getting the issues out in the open is that we know what Warren wants (his “currencies”):

- The whole story about what is going on; not just good news

- To know how big an issue is

- Doug to ask his advice where he can make contributions

- To be invited to troubleshoot where needed; to share the larger picture with the sales force

- Doug to be a team player; look beyond sales to the whole organization’s needs, not just advocate for sales

Doug didn’t consider why Warren had those needs. Isn’t it likely that Warren doesn’t want to be surprised if he were questioned by his boss and would have to admit that he knew nothing about the situation? Isn’t he accountable for the sales group’s performance? And aren’t these legitimate situational pressures? As we have noted, most people blame another’s personality (“Warren has high needs for control”), failing to consider how important the situation is.

3.

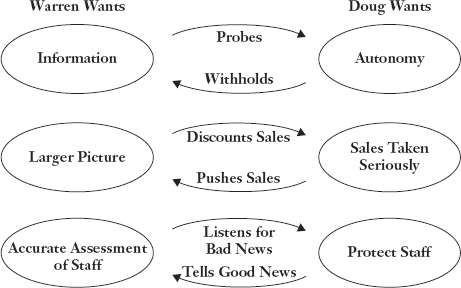

Doug didn’t see where his behavior was partially causing Warren’s response. Figure 5.1 shows that Doug and Warren are in a lose-lose exchange. Though neither can remember

when this started or

who started it, each person has legitimate concerns (currencies)—even though they trigger an undesirable response in the other.

Seeing this as an interactive “system” does several helpful things. One is to get each party to stop making negative motivational (and personality-based) attributes about the other. Warren may not be an anal micromanager who hates sales and sees the world only in negative terms. And Doug is probably not counterdependent, operating with limited perspective and paternalistically needing to protect his staff.

The second advantage of recognizing these reciprocal impacts is that it is an easier and safer way to raise the issue. If Doug accuses Warren of being a power-hungry micromanager, he’s in danger of making a serious career-limiting move. However, he could instead describe the dynamics of their relationship:

Doug: Warren, I have been thinking about some of the problems we have had in working together and I think we are in a lose-lose place. As the national sales manager, I need to run my shop—that is my job. But I think my need for autonomy has led me to hold back a lot of information, which must drive you crazy.

Warren: Damn right. It keeps me in the dark. I have to know what is going on; that’s my job.

Doug: I appreciate that and am sorry. I can now see that my withholding information gets you to probe, and the more you probe, the more I want to withhold to preserve my autonomy. That’s our screwed-up dance.

Doug could then go on and point out the other two cycles, which opens the door for some joint problem solving. This allows each to get what he wants without frustrating the other. Yes, it does require that Doug admit his part of the problem; but most bosses want their junior partners to do this.

In the best of all possible worlds, Warren would take the initiative to try to improve the relationship. After all, Doug is a very important subordinate and Warren would benefit from an open, collaborative relationship. Unfortunately, Warren didn’t initiate—and he wouldn’t be the first boss to become angry at a subordinate and not tell him. Because our goal is to show how the person with less power can change things, we will pursue the possibilities from Doug’s view—and use the “influence without authority” model to see what ideas emerge:

- Determine who has to be influenced. Doug has a choice. He could complain to Warren’s boss about how he is managed. However, that is a high-risk strategy and one he should use only as a last resort. He can talk to others about how terrible Warren is, but that provides only temporary relief and has its own risks. He can quit, which is costly in many ways. The best option would be to exhaust all possibilities in building a positive relationship with his manager. Because Warren has an open door policy, Doug only has to ask for a meeting to get it.

- Assume that each is a potential partner. Doug might find this difficult, since he’s convinced that Warren cannot be influenced. But he has to let go of the victim role. Furthermore, like many upper middle managers, Doug appears to desire total autonomy from his boss—not partnership. He can’t fathom moving from independence to interdependence. One of the ways to make the transition to real collaboration is to consider how the other might be influenced.

- Determine their power and the power gap. Although Warren has a lot of power, Doug is not without a significant amount as well. He holds a vital position, has a strong track record in sales, and is also willing to raise the important issues. Warren’s blunt and direct style reflects a considerable amount of personal power; however, he doesn’t use it to coerce or ignore Doug, or compel him to give up. And Warren’s acceptance of Doug’s bluntness in return signals that Doug doesn’t have to beat around the bush, which increases his ability to influence.

- Diagnose the world of the powerful and their currencies. Warren has overtly stated what he needs. Doug is high enough in the organization to know that a norm for senior executives in this company is “in order to look good, you need to have an answer for your boss’s questions.” He is also aware of the relationship that Warren has with his superior. He ought to realize that Warren has to keep current on how all parts of the North American operations connect. Doug needs to reflect on this a bit to understand Warren’s concerns.

- Gain access. In this case, all Doug had to do was ask for another meeting; there is no sign that Warren wouldn’t be open to one if it could be productive.

- Clarify what you need (and priorities). In the heated interchange between the two of them, Doug has also telegraphed what he wants.

- Respect for his years in sales

- Not having his judgment constantly questioned

- Autonomy: the right to make decisions in his own area

- Not be micromanaged by Warren

- Warren not to hold on to impressions; be more open in changing his mind

- Warren to support Doug in sales

But what is the relative importance of each? Are there others (such as building trust and a partnership relationship)? Which ones are the most important and what of these is Doug willing to forego?

- Define the nature of the relationship (and how each wants to be related to). Obviously, this relationship has little mutual trust. Doug will have to be specific in his exchanges in order to establish clear accountability and a way of keeping track of each one’s end of the bargain. On the other hand, he is learning that he can be direct with Warren and not have to worry about being delicate or indirect in what he says. Warren isn’t warm and fuzzy, but he doesn’t act defensive and threatened.

- Work out win-win exchanges. The objective is not just to engage in a concrete exchange, such as “give more information in return for more latitude,” but to build a partnership relationship as well. This moves it from an “arm’s-length” negotiation (“I will give you X if I can get Y”) to “how can we work more closely together?” Doug must also decide what issue to address first. Should he get more difficult matters out of the way immediately, or build up to these by discussing less critical matters? What is Doug willing to commit to? As the subordinate, he will probably have to agree to certain behaviors before he gets the responses he wants from Warren.

The previous analysis covered some of the issues that Doug pondered (while getting some coaching). The process led to this actual follow-up meeting with Warren:

Next Meeting

Doug: Warren, can we try this again? I’ve been thinking about our discussion the other day. It couldn’t have been very satisfying for you, and it sure wasn’t for me.

Warren: You’re right about that.

Doug: I’d like to see if we can’t figure out a way for both of us to get what we need; as pilot and copilot, we need to fly in the same direction. This is no way to run an airline.

Warren: So, what do you suggest?

Doug: Well first of all, let me make clear what’s bugging me and try to understand what’s bugging you. This might help us find some common ground.

Warren: That sounds okay to me. But I won’t sign blank checks. I’m not willing to abdicate my responsibilities here.

Doug: I’m not asking you to do that. I just need to feel that my 15 years in sales have earned me some respect for what I know. I need to feel that you trust me to make more than the trivial decisions, and I need you to support me in these decisions.

Warren: [More firmly] I said no blank checks. I can’t just hand over the reins to you.

Doug: I’m very clear on your need to feel that things are under control, and I realize that you get very uncomfortable when you don’t have the information you need. Without a sense of what’s going on, and assurance that I’ve done the hard analysis, you can’t give me the sort of freedom I want.

Warren: Data, Doug; that’s what anybody in my position needs. I have to base my reports on specific information.

Doug: I know you’re held accountable for the numbers. But do the folks above you ask you the sort of detailed questions that you ask me?

Warren: Look, the only way they can manage a company this size is to stay on top of the numbers. They have to challenge everyone’s assumptions and be confident that the analysis is sound, and so do I.

Doug: Okay. I’ll be sure that you get what you need from me, and maybe we can keep them off your back together. But I’m going to need some things in return.

Warren: Like what?

Doug: Can we decide upon crucial areas where you need to review my decisions, and perhaps grant me some autonomy in others?

Warren: Sure Doug; that makes sense. But it’s going to take more than that to work out all our issues.

Doug: I can see that. I’m happy to give you more information earlier, but I worry that you’ll become overinvolved and make the decisions for me.

Warren: I don’t want to make the decisions for you! I really want to honor your position as national sales manager. I just want to give some input when I have something to offer.

Doug: Okay; but what should we do when I feel you’ve moved beyond opinion giving to decision making?

Warren: Well, you could tell me that, you know. I don’t mind having you push back at me, because then at least we have something to talk about.

Doug: Hmm, well that seems fair enough. Let’s try it.

Warren: Sounds like we’ve got a deal.

Even though Doug is the subordinate, he took the initiative in this conversation. And although Warren wasn’t initially very receptive and could have been seen as resistant, Doug persisted—and he kept speaking to Warren’s needs and concerns. He also implied a desired partnership by referencing “pilot and copilot.”

However, Doug could have developed this further. He didn’t get all of his needs met, nor did he address all of Warren’s concerns. Perhaps he assumed he should be happy with what he got, or worried that Warren might think him too demanding (although Warren didn’t seem to). Doug settled for an okay resolution—thereby making the subsequent relationship only okay. It won’t be the partnership it could have been.

What else might Doug have done?

First, he didn’t have to let the conversation end there. When Warren said, “Sounds like we’ve got a deal,” Doug might have said: “Yes and I think this is a good start. But I think that there is more that we can do so that we can better work together.”

Warren: Such as?

Doug: You said the other day that you would like to give the big picture to my people. I think it would be very useful if you could attend our weekly meetings once a month, and address some major issues the company is facing.

Warren: I’d be glad to.

Doug: Good, I’ll set that up with your administrative assistant. You’re welcome to stay for the rest of the meeting; I just wouldn’t want you to get too involved in our issues. It is in both of our best interest that you let us do the heavy lifting.

Warren: I can agree to that, as long as you don’t object when I have some particular knowledge that would help in the decision—if you’re amenable to my engagement on major issues.

Doug: Fair enough; no reason why we should lose your expertise. You also said that you want me to not just represent sales. I agree with this; part of my job as a senior executive is to take account of other areas. It will be easier for me to do that if I get some support from you in regard to our challenges in this tough market, so that I don’t feel that I have to do that alone.

Warren: I’ll do that, but it is crucial that you look beyond sales.

Doug: Yes. And I realize that words are cheap and that I will have to demonstrate that to convince you. There’s just one more issue I want to address, and it has to do with personnel matters. I want to get your advice on some of the more pressing challenges, since you have a lot of experience. However, I don’t want you to immediately begin thinking negatively of whoever we are talking about. I find it difficult to change your mind when you lock into a certain judgment. What can we do about that?

Warren: Well, I don’t think I do that; I just need new data. But if you think I am, call me on it. I don’t mind you pushing me. Then we can discuss it.

Doug: Okay, that’s fair enough. I think we have gotten all the issues out on the table. If we can implement these, then I think we will be pilot and copilot flying in the same direction.

Doug was smart enough to point out that “words are cheap,” and that the subsequent actions are what counts. Although this conversation is only a start, you can begin to change your relationship by letting your boss know that you realize what he values and want to give what he wants. You can build a little bit of trust through the openness of the dialogue. However, you can only develop deep trust if each party honors their commitments.

There are several important conclusions to draw from this.

1. You don’t need complete trust to have this sort of conversation. Rather, trust will come about because of the actions you both take afterward. Doug approaches Warren by addressing the need to meet Warren’s concerns and determine his desires from Doug; it’s not particularly “soft.” Warren doesn’t hold back either, and they push on each other in an open, problem-solving way. Openly addressing valued currencies—and how to give for what you receive—tends to build a degree of trust. It’s an outcome both parties can strengthen as each delivers what was promised. And the more each delivers, the better the partnership.

2. The influence model allows for an open discussion of the issues with a minimum of accusation. The desire to understand the other’s currencies in order to work out win-win exchanges is quite different from seeking to prove that your label for the other is right.

3. You don’t have to stop early—or before your needs are met—when giving others what they want. Doug was wrong in thinking that he had to stop prematurely for fear that he might be seen as asking too much. He was giving Warren what Warren said he wanted; he therefore could have given more and requested more.

4. Despite their effectiveness, conversations like this don’t ward off all future problems. Despite their good intentions, Doug will probably feel as though Warren interferes sometimes. And Warren will occasionally believe that Doug sometimes is withholding crucial information. But if they use the influence model, each of them can discuss those incidents when they occur.

The danger for the Dougs of the world occurs the first time he thinks Warren is interfering. Rather than assuming that this person is just an intrusive micromanager, Doug should use this opportunity to explore the issue further. Maybe they weren’t clear on the vital issues or central information. Doug might say something like: “Warren, I want to do a ‘time-out’ on this task discussion, because I feel like we’re getting too much into the details. This seems like we’re going beyond the major issues we agreed to discuss during our meeting, and getting into the minor. Am I missing something?”

Warren might catch himself and agree that he has overstepped the line; or, this could lead to greater clarity. In either case, Doug shows that he is committed to making their work relationship as mutually beneficial as possible—and not trying to eject Warren from the cockpit.

5. Don’t just fix the immediate problem; discuss in a way that builds toward partnership. Doug didn’t quite see the opportunity as one where he could both solve problems and build a partnerlike relationship with his boss. This has the potential of Doug increasing his power while allowing his boss to get closer to the action—a paradoxical outcome that hadn’t occurred to him. He simply saw a struggle to preserve his power by increasing his autonomy, even at the expense of Warren’s confidence in him. A bigger opportunity to create interdependence was looming ahead of him—he simply didn’t see it.

Doug did make progress without acting phony or “kissing up” to Warren. He was straightforward, and did not resort to what many people do when dealing with powerful people: using the “sandwich” technique by surrounding a negative statement between two nice ones or compliments. The recipient in this situation recognizes it as a setup. And because it can come across as insincere, it lowers trust. Furthermore, it is ineffective because the recipient tends to ignore the compliments and overfocus on the negative. The only thing this approach accomplishes is to put more distance in an already nongenuine relationship.

There are of course other difficulties when direct reports try to work out difficulties with their manager, issues we explore in Chapters 7 through 10. But before doing that, we need to flesh out more fully what exactly we mean by “being a partner”—which we do in Chapter 6.